See the list of works for the armonica after the first set of sources.

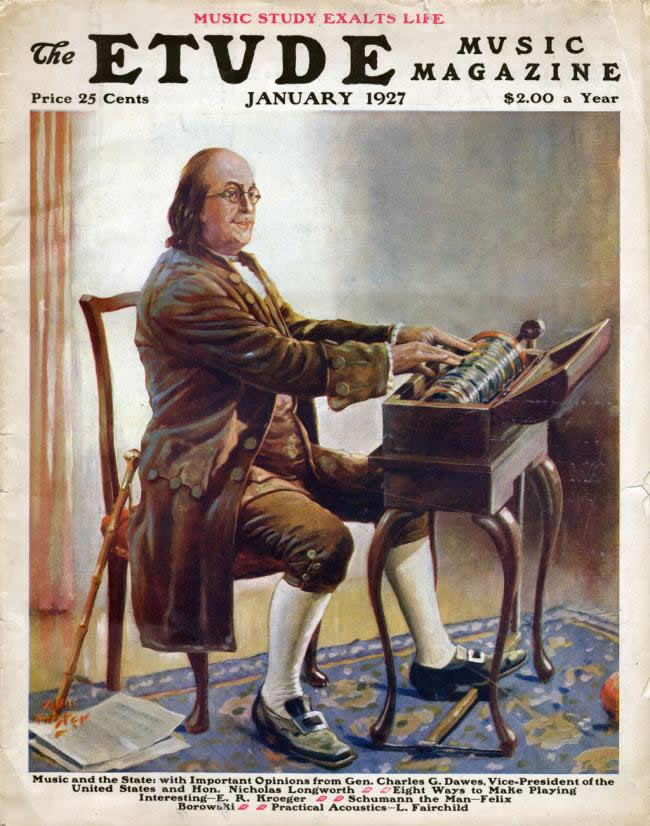

Undoubtedly, Benjamin Franklin has made many remarkable contributions to society, both tangible and intangible: he discovered electricity, influenced meteorology with his observations of storms, and helped draft the Declaration of Independence. Yet, of all his inventions, Benjamin Franklin claims “the glass armonica has given [him] the greatest personal satisfaction.” Franklin was inspired to create the glass armonica when he heard the “soft and pure sound of the musical glasses” during a performance of Handel’s Water Music. Despite Franklin’s enthusiasm, however, very few people are familiar with the instrument. Yet, such composers as Gaetano Donizetti, Ludwig van Beethoven, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart have featured it in their works. (See discussion of works written for the instrument following the source list for this article) Named after the Italian word armonia, meaning “harmony,” the armonica also has quite a few alternative names: the hydrocrystalophone, the glass harmonica, the bowl organ, and the glassychord. The glass armonica has played a significant cultural role both historically and contemporarily, as well as inspiring innovation and creativity.

Although Franklin cannot be fully credited with discovering that water-filled glasses produce music, he was the first to invent a portable version of this phenomenon. Thought to be discovered some 600 years earlier, musicians originally played single glasses, or set up a series of glasses with varying amounts of water in each glass. The musician then wet his fingers and moved them around the circumference of the bowls to produce pitches. However, this “glass harp” was difficult to move from venue to venue.

Franklin decided to adjust the size of the glass, rather than the amount of water in each glass. He subsequently situated the bowls from smallest to largest on a spindle, and secured the device in a piano-like frame where the brim of the bowls circulated through a water reservoir to keep the player’s fingers moist. This set-up allowed him to easily transport his invention without continually needing to tune each glass by adjusting the water depth. The major issue, however, was that since the sound and performance of the bowls was so dependent on having a proper shape and size, only one out of every 100 glasses blown was actually suitable for use. It was difficult to achieve the proper size and tone to produce all 48 notes, including two octaves below middle C and two above. Nonetheless, in order to expedite the creation process, Franklin hired approximately 100 workers, allowing him to distribute his instruments faster. The instrument then made its premiere in 1762 when Marianne Davies, a well-known musician from London, played music on it. Soon after, Franklin came to discover that his instrument touched the hearts of many, just as the glass harp had touched his own.

Europeans, especially, were very impressed with Franklin’s invention. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Germany’s preeminent literary figure of the 18th-19th century, described being able to detect die Herzblut der Welt—”the heart blood of the world”—while the chords of the armonica were sustained. The instrument continued to gain popularity; Franz Mesmer, a German physician who used the armonica to cure his patients, introduced the contraption to W.A. Mozart. The esteemed composer eventually wrote two pieces specifically for it: a solo work, as well as a larger quintet that included a flute, oboe, viola and cello. Beethoven, too, composed a piece for the glassychord during his time. With the help of these composers and their colleagues, at least 200 pieces for the armonica, solo or with other instruments, were written and still survive from that era to this day. Tales of miracles also began to circulate as the instrument gained more esteem. One story describes Mr. Franklin curing the Polish Princess Izabella Czartoryska of “melancholia” by playing his armonica.

Not all of the stories driven by the glass harmonica were as magical as Princess Izabella’s, however. Claims of illness began to emerge as some armonica players experienced muscle spasms, nervousness, cramps, and dizziness. Those who performed on the instrument argued that vibrations entering their bodies were causing “mental anguish.” Curt Sachs, a German musicologist from the early 1900s, suggested “the irritating permanence of extremely high partials and the continuous contact of the sensitive fingers with the vibrating bowls” was behind the deranging effect of players’ nerves. Moreover, a child in Germany died after attending an armonica performance, and the unfortunate occurrence was blamed on the instrument. The high-pitched, eerie tones even led some people to believe that the instrument had magical powers that could call upon the spirits of the dead, and some towns consequently banned the armonica entirely. It was later believed that the lead used during the manufacturing of the glass hemispheres gave players lead poisoning, which was the source of dizziness and nervousness, along with other the symptoms.

Consequently, there were several attempts to eliminate direct contact between the fingers and bowls through bows, much like those used to play string instruments. However, these attempts failed to produce results similar to those created by the fingers, as the sound lacked the desired tone. Traditional play of the instrument continued, along with claims of mental disruption. Yet, despite all of these assertions, no substantial explanation or proof ever surfaced. Franklin himself continued to play throughout his life with no symptoms, even until the time of his death.

Thanks to a company called G. Finkenbeiner Inc. (GFI), the glass armonica has been able to make a modern revival. Although technology has improved, the process to create an armonica is still painstakingly tedious. So much so, in fact, that the company only produces approximately ten units a year: “We don’t make that many anymore. [M]ainly [due to] the recession, mainly we are busy with the scientific aspects of the company and don’t pursue every interest.” Nonetheless, Gerhard B. Finkenbeiner re-invented the armonica in 1984. However, unlike the historical method of using 40% lead glass, GFI uses quartz, the purest type of glass. Heated to 3100 ℉, the glass is shaped into a long cylinder and then cut in half to create two bowls. Then, G. Finkenbeiner signifies the black keys by painting gold brims on the bowls, as Karl Leopold Röllig, a German glass armonica player and composer, did in the 18th century. This is different from the classic rainbow colored rims used to represent the seven diatonic degrees used in previous eras.

Aside from its continued creation, there have also been instruments inspired by Franklin’s original design that have made appearances in more current works. The glasschord, not to be confused with the alternative name for the glass armonica, is an arrangement of glass bars that produce a tone by striking them with small, wooden, cloth-covered hammers, much like a piano. Another descendant of Franklin’s invention is the pianino. It was created in the first quarter of the 19th century by an English firm comprised of publishers, concert agents, and piano manufacturers that went by the name of Chappell. The pianino utilized a similar hammer mechanism to create 37 notes. Additionally, the original design of the glass harmonica has made guest appearances in contemporary music. Guy Pratt, featured in Pink Floyd’s “Shine On You Crazy Diamond,”opens the song with an armonica. David Gilmour, another Pink Floyd member, also features a glass harmonica in songs “Then I Close My Eyes”and “A Pocketful of Stones” on his On an Island album.

Aside from the audible production of the instrument, those who wish to experience the armonica as historical remains may do so by viewing the few preserved instruments that still exist today. One remnant in particular is located at Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute in the Frankliniana Collection. According to John Alviti of the Institute,

This particular armonica is believed to have been made sometime between 1761-1762, according to Franklin’s instructions, by Charles James, who lived on Purpool Lane, near Gray’s Inn, in London. When Franklin returned to Pennsylvania in 1762, he brought the instrument with him. In his “Last Will and Testament,” dated 1788, Franklin gave the glass armonica to his son-in-law, Richard Bache.

Wistar MacLaren, a familial ancestor of Ben Franklin, donated the Franklin glass armonica to the Institute in 1980. Then, in a 2004 appraisal of the instrument, David Borodin of Frisk & Borodin Appraisers, Ltd,, called the glass armonica a “British Mahogany-Veneered Case Glass Armonica, designed by Franklin.”

From respected to disregarded, the glass armonica has experienced a rather unusual life. It cured some illnesses, yet seemingly caused others. It was celebrated in songs of the past but is only a featured visitor in modern pieces. Whether music enthusiasts hold the instrument’s existence in high-regard or cast it aside, it has nevertheless played an important role in history through its inspiration and innovation.

The Center wishes to thank William Zeitler and the Theodore Presser Company for their help in illustrating this article.

Sources:

- Alviti, John. “Exhibit Inquiry.” Curatorial Department of the Franklin Institute, Inc. Franklin Institute, n.d.17 Sept. 2010. <http://www.fi.edu/learn/case-files/index.php>.

- Bloch, Thomas. “The Glassharmonica.” Trans. Michelle Vadon. G. Finkenbeiner Inc., n.d. 27 Sept. 2010 <http://www.finkenbeiner.com/gh.html>.

- Boyle, Nicholas. “Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Britannica, 2010. 13 Oct. 2010 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/237027/Johann-Wolfgang-von-Goe....

- Cole, Richard, and Ed Schwartz. “Glass Armonica.” Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary. Virginia Tech, 1996. Grove Music Online. 13 Oct. 2010 <http://www.music.vt.edu/musicdictionary/textf/Frictionidiophone.html>.

- Cruice, Valerie. “Musician Summons Old Operatic Sound.” The New York Times 4 May 1986: CN32.

- David Gilmour Official Site. David Gilmour Music Ltd., n.d. 1 Oct. 2010 <http://www.davidgilmour.com/music_island.htm>.

- Finkenbeiner, Gerhard, and Vera Meyer. Leonardo. Special Issue ed. Vol. 20. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1987. 139-42. 20 Sept. 2010 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/1578329>.

- “Franklin’s Glass Armonica.” History of Science and Technology. The Franklin Institute, 2010. 5 Sept. 2010 <http://www.fi.edu/learn/sci-tech/armonica/armonica.php?cts=benfranklin-r....

- Hession, Diane. “Glass Harmonica.” Message to the author. 28 Sept. 2010. <http://finkenbeiner.com/GLASSHARMONICA.htm>.

- “Inquiring Mind: Glass Armonica.” PBS. PBS, 2002. 1 Oct. 2010 <http://www.pbs.org/benfranklin/l3_inquiring_glass.html>.

- King, Alec Hyatt. “Musical glasses.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 14 Oct. 2010 <http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/19422>.

- King, A. Hyatt. Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association. 72nd ed. Abingdon, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, Ltd., 1946. 97-122.

- Miniter, Brendan. “Founding Father of the Glass Armonica.” Wall Street Journal 15 Jan. 2004, Eastern edition: D8.

- Nelson, Kirsten. “Raise A Glass.” Systems Contractor News. 12.1 (2005): 6.

- Pollak, Michael. “Glass, Wet Fingers and a Mysterious Disappearance.” The New York Times 12 Dec. 2001: E2.

- Schott, Howard. “Glasschord.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 14 Oct. 2010 <http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/51553>.

- Schott, Howard. “Pianino.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 14 Oct. 2010 <http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/47148>.

Music Composed for the Armonica (also called Glass Harmonica)

Music composed during the height of the armonica’s popularity includes Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Adagio for armonica, K. 356 (617a), and his Adagio and Rondo for armonica, flute, oboe, viola, and violoncello, K. 617, both composed in 1791. Ludwig van Beethoven composed for the armonica, in 1815, the “Melodram” portion of his incidental music for the play Leonore Prohaska by Friedrich Dunckers. A generation later, Gaetano Donizetti’s orchestration for his 1835 opera Lucia di Lammermoor included an armonica part, notably for Act III, Scene 2, often referred to as Lucia’s “mad scene” (“Dolce suono”). Shortly before the premiere, however, Donizetti decided to use a flute in place of the armonica.

Contemporaries of Benjamin Franklin who composed for the armonica included the German composer Johann Gottlieb Naumann (1741-1801), who wrote twelve sonatas among other works for the armonica, and the German-born composer Johann Adolf Hasse (1699-1783), who lived and worked throughout Europe. Hasse composed many operas and oratorios to texts by the poet and librettist Metastasio. Hasse’s 1769 cantata L’armonica for soprano, armonica, and orchestra, was set to a poem by Metastasio.

Interest in the glass harmonica revived during the twentieth century. Richard Strauss commissioned a new version of the instrument to use in the orchestra for his opera Die Frau ohne Schatten in 1919. In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, composers who have written works for the glass harmonica include George Crumb, Orlando Jacinto García, David Horne, and Yehuda Yannay.

~~ Amanda Maple, March 2011

Sources:

- Bloch, Thomas. Notes to Glass Harmonica. Naxos 8.555295.

- Clark, Michell. “Music As Fragile As Its Material: The Classical Repertoire of the Glass Harmonica.” Experimental Musical Instruments 11:1 (Sept. 1995): 14–15.

- Digital Mozart Edition. A Project of the Mozarteum Foundation Salzburg and The Packard Humanities Institute. 11 Mar. 2011 <http://dme.mozarteum.at/DME/main/?>.

- Hadlock, Heather. “Sonorous Bodies: Women and the Glass Harmonica.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 53:3 (Autumn 2000): 507–42.

- Härtwig, Dieter, and Laurie H. Ongley. “Naumann.” In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 11 Mar. 2011 <http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/42278pg1>.

- Hoffmann, Bruno. Notes to Concert with Glass Harp. FSM 53 233 EB.

- James, Dennis, and Polly Sveda. Notes to Cristal: Glass Music through the Ages. Sony Classical SK 89047.

- King, Alec Hyatt. “Musical Glasses.” In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 11 Mar. 2011 <http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/19422>.

- Kinsky, Georg. Das Werk Beethovens: Thematisch-bibliographisches Verzeichnis seiner sämtlichen vollendeten Kompositionen. München: Henle, 1955.

- Nichols, David J., and Sven Hansell. “Hasse.” In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 11 Mar. 2011 <http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/40232pg3>.

- Restle, Konstantin. “Richard Strauss und die Glasharmonika.” Musica instrumentalis: Zeitschrift für Organologie. 1 (1998): 24-46.