You are here

5/5/1864 - 1/27/1922

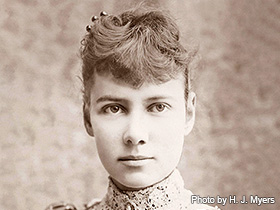

Elizabeth Cochrane, better known as Nellie Bly, was born in Cochran's Mills in 1864. Bly was the most famous woman journalist of the last 19th century.

Elizabeth Cochrane, known by her pen name Nellie Bly, was born in 1864. With little education, Cochrane was hired by an editor who took interest in her comments to the newspaper, eventually working for Pulitzer's New York World. An investigative reporter and trailblazer of so-called "stunt journalism," Cochrane uncovered popularly-read stories about conditions in a mental asylum, Mexican life, and women's suffrage, even traveling around the world in only 72 days. She died in 1922.

Born on May 5, 1864, in Cochran Mills (formerly Pitt's Mills), Elizabeth Jane Cochran (nicknamed Pink and later known by pen name, Nellie Bly) was the third child of Michael and Mary Jane (Kennedy) Cochran. Her father, founder of the town, was as an associate county judge and was once a self-made businessman (store owner, gristmill worker, and real estate speculator). Cochrane educated herself through her father's private library and writings. He died in 1869 after moving his family to Apollo, Pennsylvania, where her mother Mary Jane supported the family on a meager allowance and married John Jackson Ford in 1873. After years of abuse, Mary Jane divorced Ford in 1879, thanks to Elizabeth Cochran's testimony. Cochran was educated at the Methodist Episcopal Church in Apollo, adding an "e" to her name and changing to Cochrane when enrolling in the Indiana State Normal School in Indiana, Pennsylvania, to become a teacher. Because of financial troubles, she dropped out in less than a semester. The family moved to Allegheny City.

In January 1885, Cochrane wrote as "Lonely Orphan Girl" in response to a Pittsburgh Dispatch column titled "What Girls are Good For" by Erasmus Wilson, who worried about women's inability to properly adopt their roles of housewives and criticizing their hiring by offices and other firms. This letter gained the attention of the editor, George Madden, who immediately hired her as the paper's first woman reporter. Madden convinced her to use the pen name Nellie Bly, from a Stephen Collins Foster song. Because of her lack of formal education, Cochrane found a suitable journalism style by injecting personal opinion and providing abundant characterization detail. Her first few articles were compassionate and dealt with the plight of poor working class women, especially those that her own family lived amongst at the time.

These writings disturbed factory bosses and public officials so much so that Cochrane was reassigned to reporting on fashion and society, which would arouse less controversy. She subsequently quit as a full-time employee that November and pursued a career as a freelancer, writing about her experiences for the Pittsburgh Dispatch while traveling with her mother in Mexico. Though showing curiosity in Mexican class and societal structure, she often belittled the country in respect to her native land. These criticisms of Mexico's harshness and inequality prompted government authorities to force her departure, and she returned to the states in June of 1886.

Moving to New York, she eventually joined Joseph Pulitzer's New York World due to her experience in expos?? pieces and writings about women journalists, firmly establishing her in the journalism world by late 1887. With Cochrane's first assignment, she volunteered to commit herself for ten days to the Women's Lunatic Asylum at Blackwell's Island (now Roosevelt Island), under the name Nellie Brown. She practiced her behavior as a catatonic amnesiac before being committed to the asylum and living there in appalling conditions for 10 days.

She wrote: I have watched patients stand and gaze longingly toward the city they in all likelihood will never enter again. It means liberty and life; it seems so near, and yet heaven is not further from hell.While inside, her reports on the substandard conditions and abusive practices at the asylum were syndicated throughout the country, gaining much public awareness, helping to push for mental health care reforms, and launching Pulitzer's publication into a new age of journalism filled with narrative and dialogue.

She followed this undercover work with further investigations: domestic laborers (passing herself off as a servant), white slavery, Albany lobbyist Edward R. Phelps' political corruption, a religious sect called the Oneida Community, baby-selling market rings, swindlers, and women's achievements like that of Woman Suffrage Party candidate Belva Lockwood. Though she frequently wrote about women's political rights, Cochrane would never truly align herself with the suffrage movement.

She began her most ambitious reporting on November 14, 1889, traveling eastward across the globe as in Jules Verne's Around the World in Eighty Days. During the trip, she actually met Verne in Amiens, France. As with her Mexico travels, Cochrane wrote of her subjects in intricate and rich detail, often amusingly dismissing those odd customs that she did not understand and sympathizing with class struggles. Eager readers at home took an interest in guessing Nellie Bly's true identity and where she would travel next. Simultaneously the magazine Cosmopolitan sent reporter Elizabeth Bisland to perform the same feat, traveling in the opposite direction.

Cochrane returned to New York on January 25, 1890, beating Elizabeth Bisland and character Phileas Fogg's wager in just 72 days. However, the New York World did not reward her for her efforts, which angered her. She briefly took a hiatus to lecture, returning to the World in 1893. Her interviews of anarchist Emma Goldman and socialist Eugene Debs brought her further acclaim, along with articles on Jacob Coxey's Army and the Pullman strike. Elizabeth Cochrane's demanding career left her little time for privacy and leisure, especially when reporting on stories that frustrated and jealous co-workers could never get.

Leaving the New York World, she worked for Chicago Times-Herald for six weeks before marrying Robert Livingston Seaman, a 72-year-old millionaire industrialist of the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company, in April of 1895. Elizabeth Cochrane had various feuds with Seaman's family and the individuals with whom he associated. The next January, she was back with the New York World, focusing her journalism on mostly women's issues and covering news like the National Woman Suffrage Convention in Washington, an interview with Susan B. Anthony, proper husbandry, and even proposing that woman volunteers should help fight in the Spanish-American War.

She took a 16-year hiatus thereafter. Her husband Robert died in 1904, and she helped run his company and eventually founded the American Steel Barrel Company, which marketed the very first steel barrels in America. Financial troubles would soon arise from Cochrane granting excessive worker benefits. Cochrane joined the New York Evening Journal in 1912. Two years later, after dealing with frustrating financial matters over the inheritance from her deceased husband, as well as embezzlement by her barrel company's employees, Cochrane fled to Austria just in time for the outbreak of the First World War. The Evening Journal carried her battlefield reporting from the Russian and Serbian fronts, unbeknownst to Cochrane that her support for the Austrians and calls for their aid would eventually be enemy collaboration after the US declared war on them. This sympathy would lead to some complications with the authorities upon her return to America in 1919.

By war's end and with her funds exhausted, Cochran wrote advice columns for the Evening Journal, remaining strong in her activism in assisting orphaned children and the poor. With more women being accepted into journalism, her stories did not invite as much public interest anymore. Alone and poor, she died of pneumonia, brought about by heart disease, after three short weeks on January 27, 1922, at St. Mark's Hospital in New York City and was buried in the Church of the Ascension Cemetery. Journalist Arthur Brisbane would praise her in the Evening Journal as the best reporter in America. In an age of sensationalist "yellow journalism," Elizabeth Cochrane remains best known as one of the earliest investigative reporters in America and pioneer of stunt journalism, utilizing simple first-person narration alongside striking detail and heartfelt opinion. She remains popular for her asylum reporting, her defense of the abused in society, her travels in Mexico, and her reenacting of Phileas Fogg's circumnavigation, though her few published works have gone unnoted since, for the most part.

- Ten Days in a Mad-house; or, Nellie Bly's Experience on Blackwell's Island. Feigning Insanity in Order to Reveal Asylum Horrors. New York: N.L. Munroe, 1887.

- Six Months in Mexico. New York: J.W. Lovell, 1888.

- The Mystery of Central Park: A Novel. New York: G.W. Dillingham, 1889.

- Nellie Bly's Book: Around the World in Seventy-Two Days. New York: Pictorial Weeklies, 1890.

- Brown, Lea Ann. "Elizabeth Cochrane." Dictionary of Literary Biography. Volume 25: American Newspaper Journalists, 1901-1925. Ed. Perry J. Ashley. Detroit: Gale, 1984.

- Delany, Laurie. "Nellie Bly." Dictionary of Literary Biography. Volume 189: American Travel Writers, 1850-1915. Ed. Donald Ross and James J. Schramer. Detroit: Gale, 1998.

- "Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman." The Gale Literary Database: Contemporary Authors Online. 3 March 2003. 21 February 2007. <http://galenet.galegroup.com/>.

- Keillor, Garrison. "Today is the birthday of journalist Nellie Bly." The Writer's Almanac. 5 May 2013. 9 May 2013. <http://app.info.americanpublicmediagroup.org/e/es?s=1715082578&e=16391&elq=6738a5d0187e44d6811bfbe8cbd1979d>. Web address inactive.

- Kroeger, Brooke. "Bly, Nellie." American National Biography Online. February 2000. 23 February 2007. <http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-01472.html>.

- Randall, David. The Great Reporters. Ann Arbor, MI: Pluto, 2005.

Photo Credit: H. J. Myers. "Photograph of Nellie Bly." c. 1890. Photograph. Licensed under Public Domain. Cropped to 4x3. Source: LOC. Source: Wikimedia.