You are here

4/10/1822 - 2/9/1854

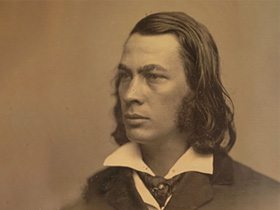

Born in Chester County, social reformer George Lippard wrote a number of urban expose novels, including 1844's The Quaker City.

George Lippard was born on April 10, 1822, in West Nantmeal Township, in Chester County, Pennsylvania. His father was Daniel B. Lippard. However, he was left in the care of his two aunts and grandfather in Germantown, Philadelphia. His father died in 1837, leaving him with nothing. Hence, Lippard experienced the hardships of the workers firsthand. He became sympathetic to the workers' cause and he became a leading activist in reforming their working conditions. His major works include The Monks of Monk Hall (1844) and Blanche of Brandywine (1846). He also founded a labor union, The Brotherhood of the Union in 1849. Lippard died on February 9, 1854, in Philadelphia.

George Lippard was born on April 10, 1822, in West Nantmeal Township, Chester County, on the farm of his father, Daniel B. Lippard. His father was crippled, while his mother suffered from tuberculosis. As a result, in 1824, Lippard and his family moved to Germantown, Philadelphia, where he and his sisters were left in the care of their grandfather and two unmarried aunts. However, money was very tight, so his aunts were forced to sell their home and move into Philadelphia. At age 15, Lippard was sent to school in upstate New York to train for the Methodist ministry. However, he was against some of the cruel practices of the director at the school and dropped out. After his father's death in October 1837, Lippard realized that he was not given any share of an estate worth $2000, leaving him completely penniless. Thus, to support himself, Lippard took up several law-assistant jobs. He was, essentially homeless, sleeping in abandoned studios and buildings. This gave Lippard a first-hand look at all the effects of the Depression of 1837-1844. This eye-opening experience caused Lippard to become a writer for the masses.

His first work was Lady Annabel (1842), which in essence, was not really to save the masses, but to entertain them. Lippard felt that this was the best way of saying that he was with the people. Though it was not exactly a novel that pushed social norms it did win praise from Lippard's friend at the time, Edgar Allan Poe. While working on Lady Annabel, Lippard was introduced to John S. Dusolle, who was the editor of the Spirit of the Times, a Philadelphia newspaper. For the newspaper, Lippard wrote two satirical columns, The Sanguine Poetaster and Our Talisman. These two columns were very controversial because they attacked other writers and the rich. Lippard then left the Spirit of the Times and joined another Philadelphia newspaper, The Citizen Soldier, where he continued to have a large number of readers. These newspapers allowed Lippard to establish himself as a controversial, leading, writer.

By the years 1842-1852, Lippard was producing a mass amount novels, essays, and lectures. His average was one million words annually and was mainly directly towards America's ruling class. However, Lippard reached his climax with his novel, The Quaker City; or The Monks of Monk Hall. A Romance of Philadelphia Life, Mystery, and Crime, which he wrote in 1844. It was a satirical novel, which had a culmination of various ideas such as Gothic horror, romantic eroticism, and social satire. It soon became the best-selling novel in America selling 60 thousand copies in its first year. While many of the elite class were offended by Lippard's work, the working class took his side. His popularity lent him a hand each time he published a book. As a result, during the 1840s Lippard's annual salary was $3000-$4000, a huge sum at the time. By 1847, Lippard married Rose Newman, who he had courted for three years, in an unconventional wedding ceremony, once again highlighting his opposition to the norms of society at the time. By this time, Lippard was viewed as the lead spokesperson for the poor and a radical reformer against the elite.

The climax of Lippard's career came with three events. First, by the late 1840s, Lippard became involved with state and national politics. When he did not win the position of district commissioner of Philadelphia, Lippard became involved in Zachary Taylor's presidential campaign. Lippard campaigned actively for Taylor because he felt that Taylor's policies were directed in favor of the workers. Taylor won the election in 1848. However, Lippard later found that his ideas would not be heard through Taylor when Taylor openly spoke against the European revolutionaries. As a result of his letdown, Lippard started the first reform newspaper, the Quaker City Weekly, which he was the editor of for two years. The newspaper reached fifteen thousand people. In addition, Lippard wrote five novels and many essays, which promoted land reform and militant labor combination. This provided a good basis for the labor organization Lippard founded in 1849.

The Brotherhood of the Union was started in June of 1849 and was the first of its kind in America. Ideas and symbols associated with patriotism were used for the brotherhood as well as symbols from the American Revolution were used in the officer titles and rituals. Lippard's vision for his brotherhood was the unity of all the workers. The Brotherhood of the Union promoted all the major labor reforms of the period, such as a shorter workday, land reform, election reforms, and education reforms. The Brotherhood grew with rapid speed and there were requests for charters into the Brotherhood from all over Pennsylvania and other states, such as Georgia, Texas, and Florida. By October of 1850, there were little groups of the Brotherhood in nineteen states. In addition, Lippard was then elected the "Supreme Washington" at the first annual convocation in Philadelphia again, keeping with the patriotic themes of the Union. For the next four years, Lippard dedicated the majority of his time supervising the Brotherhood and lecturing in various states on its behalf. In addition, he published a book containing a collection of his labor writings, known as The White Banner (1851). Lippard had reached the climax of his career.

Between the years of 1848 and 1851, Lippard witnessed several tragedies. His sister, Harriet, and two young children, Mima and Paul, all died from tuberculosis. However, this was not the end of his tragedies. In 1851, Lippard's 26-year-old wife, Rose, died. By this point, Lippard had reached an all-time low and was suicidal, even attempting to throw himself into Niagara Falls, only to be stopped by a friend. In addition, Lippard had come to accept the fact that he would most likely die by the same disease that had killed most of his immediate family. He wrote a long novel in 1853, and spent most of his remaining time lecturing through the Midwest. He then came back to Philadelphia to supervise the annual convocation of the Brotherhood in October. However, by December, his health was deemed so poor that he was confined to his house. This did not stop Lippard from fighting for the poor. He spent the next two months writing a long newspaper serial story, which protested against the Fugitive Slave Law. He was then deemed too ill to write, so he sketched about 20 stories in pictures. George Lippard died, while at his desk, on February 9, 1854, from tuberculosis. His funeral was a huge affair, with hundreds of his readers and followers from the Brotherhood attending.

Books

- The Ladye Annabel; or, The Doom of the Poisoner. A Romance by an Unknown Author. Philadelphia: 1842.

- The Quaker City; or, The Monks of Monk Hall. Philadelphia: Leary, Stuart & Company, 1844.

- Blanche of Brandywine. Philadelphia: G. B. Zieber & Co., 1846

- The Nazarene; or The Last of Washington. Philadelphia: T. B. Peterson. No. 102 Chestnut Street, 1846.

- Thomas Paine, Author-Soldier of the American Revolution. Philadelphia: 1852

- The Midnight Queen.New York: Garrett & Co. 1853.

- The Empire City; or New York by Night and Day. Philadelphia: T.B Peterson & Brothers, 1853.

- New York: Its Upper Ten and Lower Million. Cincinnati: Queen City Publishing House, 1853.

Short Stories

- The White Banner. 1851.

- Elliot, Jas B. Lippard, George: Thomas Paine, Author-Soldier of the American Revolution. Philadelphia: 1852.

- Darley, Steve. "The Dark Eagle: How Fiction Became Historical Fact." Archiving Early America. 21 Feb. 2007. <http://www.earlyamerica.com/review/2006_winter_spring/dark-eagle.html>.

- "George Lippard." Biographical Directory, an Eclectic Guide. 21 Feb. 2007. <http://www.geocities.com/CollegePark/Quad/6460/bio/L/ippard.html>. Web address inactive.

- "George Lippard." The Fraternitas Roae Crucis. 21 Feb. 2007. <http://www.soul.org/Legend.html>. Web address inactive.

- Grazia, Emilio De. "Poe's Devoted Democrat, George Lippard." Poe Studies/Dark Romanticism. 1 Sept 2002. 21 Feb. 2007. <http://www.eapoe.org/pstudies/ps1970/p1973102.htm>.

- Reuben, Paul P. "Chapter 3: George Lippard" PAL: Perspectives in American Literature- A Research and Reference Guide. 29 Mar. 2007. <http://web.csustan.edu/english/reuben/pal/chap3/lippard.html>. Web address inactive.

- Reynolds, David S. George Lippard, Prophet of Protest. New York: Peter Lang, 1986.

- "The Quaker City; or, The Monks of Monk Hall: A Romance of Philadelphia Life, Mystery, and Crime." 21 Feb. 2007. <http://www.amazon.com/rss/people/A117AVD9JNUCVZ/reviews>. Web address inactive.

- Voller, Jack G. "George Lippard". The Literary Gothic. 13 June 2006. 21 Feb 2007. <http://www.litgothic.com/Authors/lippard.html>. Page content replaced.

Photo Credit: "Photograph of George Lippard." c. 1850. Photograph. Licensed under Public Domain. Cropped to 4x3. Source: Wikimedia.