You are here

3/23/1737 - 8/31/1818

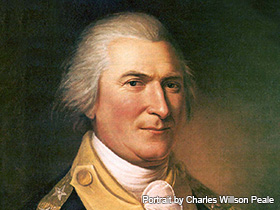

Arthur St. Clair was a General in the Revolutionary War and the first Governor of the Northwest Territory.

Born on March 23, 1737, in Scotland, Arthur St. Clair was fortunate enough to attend medical school for a short while. Following his mother's death, St. Clair joined the British army in the French and Indian War overseas. During the American Revolution, St. Clair became a true colonist and aided George Washington in the Battle of Trenton. Due to this relationship and the belief that he was a capable leader, St. Clair was able to work his way up to becoming President of Continental Congress and Governor of the Northwest Territory. However, his loss of Fort Ticonderoga in 1777 and defeat at the hands of the Native Americans in 1791 left his reputation permanently tarnished. St. Clair was forced to give up his titles. He died in poverty in Greensburg on August 31, 1818.

Arthur St. Clair was born on March 23, 1737, in Thurso Castle, Scotland, to William and Margaret St. Clair. His family's ancestral line consisted of varying levels of Norman noblemen who were famous in England and Scotland; however, St. Clair's parents had lost this fortune. As the youngest son, St. Clair's father William had not inherited land from his ancestors. Nevertheless, St. Clair's family maintained a respectable home, and his father was able to provide for his children as a reputable merchant. William unfortunately died when Arthur was young, and Margaret was given the burden of educating their son.

Despite the lack of a wealthy background, St. Clair was able to attend the University of Edinburgh to study medicine for a time. Indentured to Doctor William Hunter, a renowned physician in London, St. Clair was well on his way to becoming a successful doctor. However, when tragedy struck and his mother died in the winter of 1756, St. Clair left his apprenticeship with Doctor Hunter. With nothing left for him in Europe, St. Clair decided like many energetic young men of the time to enlist in the military. Barely twenty years old, St. Clair left his homeland and headed for America with the British army to aid in the French and Indian War. During his time in the British army, St. Clair had the good fortune to serve under several notable commanders. He helped in the capture and siege of Louisbourg in Nova Scotia under General Jeffrey Amherst and also the siege of Quebec under General James Wolfe. After Louisbourg, St. Clair was appointed lieutenant for his heroic actions during the siege.

When his regiment was stationed in Boston, St. Clair met his soon-to-be wife, Phoebe Bayard. They married in 1760 and had seven children. The wife of St. Clair was no commoner; she was related to the then Governor of Massachusetts. Her good standing later enabled St. Clair to purchase a vast amount of land near Ligonier, grounding him in Western Pennsylvania.

As St. Clair's fortune grew, his position began to rise as well. He built several mills on his land and became a justice of the court in Westmoreland and Bedford counties. This new status became everything to St. Clair as he expended his resources to develop a four-thousand acre estate. St. Clair truly appreciated the power he gained in Ligonier but invested himself entirely into promoting his reputation. As historian Warren Van Tine of Ohio State University wrote in Builders of Ohio: A Biographical History, "St. Clair clearly believed that ordinary people should defer to their established leaders, and relished his own status as a community leader."

St. Clair's stable position in America may account for his changed loyalty during the Revolutionary War. Just as it appeared easy for him to leave his homeland, it was even easier for him to break his allegiance with England and side with the patriots in America. St. Clair once again worked his way to the top of the army by gaining the fidelity of none other than George Washington. As a brigadier general in Washington's Continental army, St. Clair's former training enabled him to suggest a strategy to Washington that aided in the victory for the colonies at Princeton. St. Clair's accomplishment was unmatched in Pennsylvania: as descendant Arda Bates Rorison wrote in Major-General Arthur St. Clair: A Brief Sketch, "he was the only officer from Pennsylvania who became a major general during the Revolution."

As St. Clair's power in the colonies escalated, so too did his responsibilities. In March 1777, George Washington placed St. Clair in command of Fort Ticonderoga near Lake George in New York. Because Washington believed any attack on the fort by the British would come from the south, he left St. Clair with only a small number of soldiers. When British troops approached Fort Ticonderoga from the north, St. Clair knew his meager two-thousand men were no match for a British force four times the size, and he retreated in an effort to preserve what little men the Continental Army had left in the north. Accused of cowardice and court-martialed, St. Clair was acquitted of all charges, yet the retreat left a mark on his status as a respectable commander. In response to his retreat at Ticonderoga, Arda Bates Rorison quotes St. Clair as commenting, "I knew I could save my reputation by sacrificing the army; but were I to do so, I should forfeit that which the world could not restore and which it cannot take away, the approbation of my own conscience." By retreating, St. Clair was able to save a portion of the small Continental army's men, ensuring that his forces would live to fight another day.

Although St. Clair was criticized for his actions at Ticonderoga, his loyalty to the army could not be disputed. Historian Frazer Ells Wilson reported St. Clair as remarking, "I hold that no man has a right to withhold his services when his country needs them. Be the sacrifice ever so great, it must be yielded upon the altar of patriotism." Clearly St. Clair's sacrifice was the portion of his reputation that was tarnished in his wise decision to retreat.

St. Clair's popularity on the political front began to grow as a result of his education, loyalty, and leadership to the new nation despite his temporary setback in the Revolutionary War. A Federalist, he was elected into Congress in 1785 and subsequently elected as President in 1787. His time as president of Congress under the Articles of Confederation was marked by great accomplishments for the United States. First and foremost, the current form of the Constitution was adopted in 1787. In addition, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 established a precedent by which new states would be admitted to the United States and banned slavery in any new territory acquired by the United States.

St. Clair was appointed Governor of the new territory as his popularity peaked and was given authority over the territory that now encompasses Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. His new position granted him even more power in the political sphere. He not only served as executive officer but also as lawmaker for the territory. Unfortunately though, St. Clair's popularity in the Midwest was quite different from that in Pennsylvania. As Frazer Ells Wilson noted in Arthur St. Clair: Rugged Ruler of the Old Northwest, "St. Clair was considered a foreigner of distinguished lineage who owned a large estate, ranking him as an aristocrat, at a time when men were emphasizing the equality of all men, and trying to set up a new order."

Expansion westward by American settlers meant that conflict with the Native Americans was inevitable. When in 1791 the government wanted to establish a military post in the Northwest that would prevent any further attacks on Americans, St. Clair was granted position as the General in the army. Not well informed on his location and unaware of the number of Native Americans surrounding him, St. Clair's small force was ransacked by the Native Americans in what has been named St. Clair's Defeat at Wabash. Although sick at the time, St. Clair's illness was no excuse for the army's humiliating loss, the worst of the Americans at the hands of the Indians.

Because little information was available to the public at the time, St. Clair's defeat once again brought shame to his reputation. But modern day accounts contest St. Clair as the cause of failure. In the article "American Indian Military Leadership: St. Clair's 1791 Defeat," historian Leroy Eid remarked, "The battle in which his army was almost annihilated is unfairly named after him, even though the record reveals widespread errors, cowardice, and incompetence in St. Clair's army before, during, and after its losing performance." Nevertheless, public opinion of St. Clair at the time began to have an effect on St. Clair's political power. According to Warren Van Tine, "St. Clair's defeat greatly damaged his ability to govern the Northwest Territory, since few pioneers now respected him." Because the circumstances surrounding the battle were clouded, so were the views of St. Clair himself.

St. Clair asked for a congressional committee to investigate the battle in an attempt to salvage his reputation. Though they found that St. Clair was not at fault, St. Clair resigned his position in the army yet remained governor of the territory. He began to detest the Northwest Territory because of its negative effect on his career. Warren Van Tine quotes St. Clair as claiming as if he felt he were "a poor Devil banished to another Planet" when residing in the area. St. Clair remained Governor of the territory until Thomas Jefferson removed him from power in 1802.

St. Clair's position as Governor was one of his last claims to power. After being removed from office by Jefferson, he settled back in the Ligonier Valley. Facing debts from loans he had given out during the Revolution, St. Clair attempted to acquire money by becoming involved in part of the new and growing iron industry. In addition, he attempted to rebuild his flouring mill, though neither endeavor brought him much success. Unfortunately, St. Clair's economic problems caught up with him, and sheriffs began to sell his property for the debts he had accumulated.

In an effort to gain back some of the money he lost, St. Clair petitioned Congress for what he believed was money due from his services to the country. Some of this money was granted, however, the United States House of Representatives only later recognized that what they had granted in recompense was not sufficient. St. Clair suffered in poverty. On his way to Youngstown in 1818 to buy some goods for his family, St. Clair fell off of his wagon. Found unconscious on the side of the road, he lingered between life and death but finally passed away on August 31. He is buried in St. Clair Park in Greensburg.

The realization of Congress had come too late. In 1890, the government decided to build a monument for St. Clair's grave. In setting aside the funds for the monument, Congress declared, "Perhaps there was not a prominent character of revolutionary period, with the exception of Morris, who gave so much of his life, his service, and means to America as did St. Clair, and there was none, with that exception, so poorly recompensed." Because the failures of St. Clair's life had been stressed more than the successes, St. Clair had not been given the recognition that he deserved.

However, St. Clair's legacy as a capable leader was preserved in two places in Pennsylvania that now bear his name: Upper St. Clair Township and St. Clairsville. Just south of Pittsburgh, Upper St. Clair is currently the home of over 20,000 residents. The township was named for St. Clair after its establishment in 1788 as a tribute to St. Clair's dedication to Western Pennsylvania and his support of the land as Pennsylvania's territory. The name stuck even after St. Clair's defeat at the Wabash River. About 10 square miles, Upper St. Clair was named one of the best places to live in 2009 by the U.S. News and World Report. St. Clairsville, settled in 1820, is located in Bedford County and is considered a small borough. It too bears St. Clair's name in an effort to preserve the successes of the general's life.

Ligonier and Greensburg, though not explicitly named after St. Clair, are two regions in Westmoreland County that still reflect the influence of St. Clair is Western Pennsylvania. Ligonier is primarily where St. Clair purchased and created his four-thousand acre estate. Parts of his home, called the Hermitage, are preserved in the Fort Ligonier Museum. Greensburg in Westmoreland County serves as St. Clair's burial site and place of his monument. St. Clair Park, where he is buried, clearly displays his name.

With the belief that St. Clair's legacy should not be forgotten, in 2009 the monument was rebuilt by Westmoreland County officials. Though a man who was once scorned for his failures, St. Clair has recently received the accreditation he deserves. For as commissioner Charles Anderson noted, "This [history] is the genesis of Western Pennsylvania."

- Cunningham, Libby. "Monument dedicated to Arthur St. Clair restored, rebuilt on Route 30." Tribune-Review. 17 Aug. 2009. 8 Nov. 2009. <>http://www.pittsburghlive.com/x/pittsburghtrib/news/westmoreland/s_63862....

- Edel, Wilbur. Kekionga! : The Worst Defeat in the History of the U.S. Army. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1997.

- Eid, Leroy V. "American Indian Military Leadership: St. Clair's 1791 Defeat." Journal of the American Military History. 57:1 (1993: Jan.): 71-88.

- Griswold, Katherine and Suellen Welty. An Historical Album: Upper St. Clair. Upper St. Clair: Lang, 1977.

- Know Your Community: Upper St. Clair, PA. Upper St. Clair: Upper St. Clair Board of Commissioners, 1986.

- Mullins, Luke. "Best Places to Live 2009." U.S. News & World Report. 8 Jan. 2009. 22 Nov. 2009. < >http://www.usnews.com/money/personal-finance/real-estate/articles/2009/0....

- Pierce, Michael, and Warren Van Tine. Builders of Ohio: A Biographical History. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2003.

- Rorison, Arda Bates. Major-General Arthur St. Clair: A Brief Sketch. New York: 1910.

- St. Clair, Arthur. United States. House of Representatives. A Narrative of the Manner in Which the Campaign against the Indians, in the Year One-Thousand-Seven Hundred and Ninety-one, was Conducted, Under the Command of Major General St. Clair. Philadelphia: Jane Aitken, 1812.

- United States. Dept. of Treasury. Letter from the Secretary of the Treasury, Transmitting Statements of the Accounts of General Arthur St. Clair. Washington: Dept of Treasury, 1818.

- United States. House of Representatives. Report of a select committee to whom was referred on the seventeenth instant the memorial of General Arthur St. Clair. Washington: Washington A. & G. Way, 1811.

- United States. House of Representatives: Committee on the Library. Grave of Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair. 25 April 1890. 27 Oct. 2009.

- Wilson, Frazer Ells. Arthur St. Clair: Rugged Ruler of the Old Northwest. Richmond, VA: Garrett and Massie, 1944.

For More Information:

- A Lost Warrior. Dir. Dennis Rody. Post-Gazette.com Multimedia, 2009. 29 Nov. 2009 <>http://www.post-gazette.com/multimedia/?videoid=102605>.

- Roddy, Dennis B. "Buried in Greensburg, a forgotten Revolutionary." Pittsburgh Post Gazette 22 Nov. 2009: A1+.

Photo Credit: Charles Willson Peale. "Portrait of Arthur St. Clair (1737-1818)." 1782. Portrait. Licensed under Public Domain. Cropped to 4x3. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Independence National Historical Park, Philadelphia.