You are here

12/19/1858 - 11/9/1919

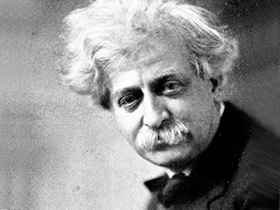

Philadelphia literary critic Horace Traubel is best known as a chronicler of the poet Walt Whitman.

Shortly after turning 16, Traubel moved from Camden, New Jersey, to Philadelphia to work in his father's lithographic shop. He became the Philadelphia correspondent for the Boston Commonwealth. He moved back to Camden and continued spending a large amount of time with Walt Whitman. He moved back to Pennsylvania in 1890, two years before Whitman's death. He remained in Philadelphia (even after being asked to resign from his job at the bank for publishing an attack on one of the most influential businessmen in Philadelphia) until a year before his death, when he moved to New York to be closer to his newly-married daughter. After resigning from the bank in 1902, he lived solely off the proceeds of his publications, mainly those in the Conservator. He died in 1919 in Ontario, Canada, while attending an event in honor of Walt Whitman.

Horace Traubel personified the very best that the Progressive Era had to offer. He never shied away from using the newest technology, yet was also among the first to cry out against the military build-up employing it. He was in almost every sense a humanist. He never lost hope in the teleological movement of humankind towards its betterment.

Traubel, born December 15, 1858, was one of seven siblings in a house where religion was not given the importance it was in many other places in the 1850s. His father was of Jewish background while his mother grew up in the Christian tradition. Maurice Traubel, Horace's father, had given up his heritage after being kicked out of his house for refusing to follow the strict teachings of the Talmud. This decision had great influence on how the Traubel children were raised and their consequent views of the world.

Horace Traubel dropped out of the public school in Camden at twelve years old in order to help at his father's stationary store. Shortly after, he became a printer's devil, which involves doing the grunt work throughout the printing process. He finally moved on to a jack of all trades position at the Camden Evening Visitor. At this job, Traubel became skilled at every position necessary to printing a paper. Traubel was even able to tell whether or not an ink was the right grade by looking at it. Traubel never received any formal training in editing or printing, but the jobs he had throughout his youth prepared him for his literary pursuits as an adult.

The most significant part of Traubel's life was his friendship with the poet Walt Whitman. The pair began meeting when Traubel was twelve or thirteen years old. They spent large amounts of time discussing current political thought, existentialism, prose, and poetry. The fact that Traubel dropped out of school shortly after this was not lost on Whitman, who said that Traubel's talents would have been squandered in a classroom. One of the major projects of Traubel's life was his Complete Works of Walt Whitman, which involved ten volumes of detailed notes he had taken during their twenty-two years of friendship. Traubel also collected letters, poems, and notes that Whitman had either written or received.

As a young adult, Traubel dropped his ties with organized religion and also took a position as a clerk in The Farmer's and Mechanic's Bank in Philadelphia. It was here that Traubel first became familiar with what he later on called the "oppression of the common laborer." In the bank, Traubel was in charge of wages and of firing certain employees, essentially since he was a bank manager. He was eventually fired from his position at the bank based on his boisterous political views, though the bank cited an ancient rule stating that no employee could maintain his position while at the same time having any alternate vocation. Because his private paper, The Conservator, was more important to him, he decided to give up his job at the bank.

Later on, Traubel said that he could identify with the common worker so well because he had spent 34 years of his life working for those who oppressed them. Traubel thought big business oppressed the common worker in terms of economic enslavement, and he believed businesses tried to confine the mental and spiritual range of their employees.

After losing his job at the bank, Traubel became a full time writer. He had originally published a monthly magazine called The Conservator with his Society for Ethical Research, which was supposed to be used as a tool to connect the more radical factions of those groups who were, despite dogmatic differences, striving for the same political, social, and economic equality within the United States. The magazine was meant to be a "means of communication within the ethical community at large, which would otherwise have had no frequent channel of intercourse," as Traubel himself put it in an interview with David Karsner.

Traubel saw himself as an essential tool in connecting otherwise disjointed organizations. He opposed radicals in the political sphere because, despite their political correctness and objectivity, they often lost sight of the greater goal of all social reform organizations. It was within this mode of thought that Traubel also denounced any official party program of platform. He saw them all as inherently restraining. Traubel never shied away from social experimentation or from challenging the status quo. He challenged all people to think for themselves and in terms of the best interests of society at large, not simply of their own welfare or that of any particular faction. Traubel was a highly active speaker against discrimination and racism.

In his day-to-day life, Traubel was incredibly active. He normally slept no more than four hours per day. He ate several extra meals to accommodate for the lack of sleep, and he refused to wear an overcoat, even in subzero weather. He would routinely spend two to three hours per day writing letters to his friends as well as finding and sending them appropriate clippings from other newspapers.

Traubel was also extremely quick to recognize the contributions of others. In interviews he often stressed how little work he could have accomplished or how little he would be worth without the incredible devotion he had received from several close friends and working associates. It was in this way that Traubel was so humanistic. He had incredible enthusiasm for life in general and was incredibly optimistic. Traubel never seemed to tire of or become overly frustrated with the constant banalities and downfalls of human beings.

During his lifetime there was a commune established outside of Philadelphia that specialized in making crafts in order to sustain itself. Traubel often wrote about it in a paper called The Artsman. He once wrote, "Rose Valley is not altogether a dream or wholly an achievement. It is an experiment. It is also an act of faith. It is not willing to say what it will do. It is only willing to say what it is trying to do. Rose Valley pays a first tribute to labor." Later he continues, "Rose Valley may fail. But its faith cannot fail. The wisdom or the backbone of its co-operative force may beak in the test. But the experiment is worth putting to the proof."

A poem published in Optimos perhaps best sums up Traubel's attitudes towards life:

I have had such joy on the earth, So many of the things that seemed to have started wrong have ended right, So many of the ecstasies have come out of so many of the sorrows of the years, So many of the most clouded mornings have so opened the way to the most sunny afternoons. Evil has everywhere and always so refused to stop with evil and has gone on to good, Death has everywhere and always so refused to stop with death and has gone on to life, That I stand happy and satisfied surveying the tangle through which I have broken.

Traubel died in 1919. During the last few years of his life he took every possible opportunity to speak out against World War I. He saw it as the polar opposite of what could be considered a good or moral use of technology. He thought it was a waste of human life, technology, and he argued it was a result of capitalistic and imperial endeavors by all the countries involved. The greed that he saw going on at the national level was the same that he had been speaking against for years at a local worker versus employee level. He was heartbroken by the wanton destruction that had taken place in Europe. He despised the people that had started the war and then had so arbitrarily made its peace.

A month before he died, Traubel took a final trip to Canada to see a park opened in the name of Walt Whitman. During the ceremony there were many famous socialists and reformers, and Helen Keller asked the audience to give Traubel a standing ovation in recognition for both his great work on Whitman and for his tireless social commentary and activity. It was an incredible culmination to his career to be recognized by so many people who Traubel himself held in such high regard.

Nonfiction

- (Editor) Camden's Compliments to Walt Whitman, May 31, 1889: Notes, Addresses, Letters, Telegrams. Philadelphia: David McKay, 1889.

- With Walt Whitman in Camden (diary). Boston: Small, Maynard & Company, 1906.

- (Editor) At the Graveside of Walt Whitman: Harleigh, Camden, New Jersey, March 30, 1892; and, Sprigs of Lilac. Philadelphia: Billstein & Son 1892.

- (Editor with Richard Maurice Bucke and Thomas B. Harned) In Re Walt Whitman. Philadelphia: David McKay, 1893.

- (Editor) Complete Writings of Walt Whitman. 10 vols. New York: G.P. Putnam's, 1902.

- Chants Communal. Boston: Small, Maynard & Company, 1904, 2nd edition, 1914.

- (Editor) Walt Whitman, an American Primer, with Facsimiles of the Original Manuscript. Boston: Small, Maynard & Company, 1904.

Periodicals Editor and Writer

- Optimos. New York: B. W. Huebsch, 1910.

- Collects. New York: A. and C. Boni, 1914.

- The Consevator. Philadelphia PA: Self-Published, 1890-1919.

- Bain, Mildred. Horace Traubel. New York: Albert and Charles Boni, 1913.

- Denison, Flora MacDonald. "A Dedication and a Death." Walt Whitman's Canada. Ed. Cyril Greenland and John Robert Colombo. Willowdale, Ontario: Hounslow, 1992. 196-200.

- Karsner, David. Horace Traubel: His Life and Work. New York: Egmont Arens, 1919.

- Walling, William English. Whitman and Traubel. 1916. New York: Haskell House, 1969.

Photo Credit: "Horace Traubel." 1916. Photograph. Licensed under Public Domain. Cropped to 4x3, Filled background. Source: Wikimedia.