You are here

3/3/1826 - 1/10/1909

Industrialist Joseph Wharton founded Swarthmore College.

Born in 1826, Joseph Wharton was a prominent Pennsylvanian who presided over some of the most astute educational, industrial, and economic institutions the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania has ever seen. Wharton was once the largest stockholder of Bethlehem Steel. Wharton died in 1909, but his name and legacy live on today as the namesake of the Wharton Business School at the University of Pennsylvania, which is regarded as one of the best business schools in the world. Wharton also founded one of the most prominent liberal arts colleges in the United States, Swarthmore College.

Joseph Wharton was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on March 3, 1826, to prominent Quaker parents, Deborah and William. Both of his parents were deeply interested in education and demanded their children receive proper education in their early years. They enlisted the services of many tutors to come to their home on Spruce Street. Young Wharton showed proficiency in the arts, which persuaded his parents to provide him with a greater measure of formal schooling than his other siblings. However, Quaker beliefs at the time did not support higher education; therefore, Wharton was sent to nearby Chester County to learn farming in 1842.

After Wharton learned farming, the young industrialist focused his attentions on business and commerce. Wharton made his return to Philadelphia, a city making a name for itself in advances in chemistry research in the 1840s. Wharton went to work for his brother Rodman who had a venture cottonseed oil business. After four years in business together, the Wharton brothers dissolved their partnership in 1849, and Wharton began manufacturing bricks. By the spring of 1850, Wharton entered into a partnership with an owner of several large brickyards, Joseph B. Matlack. Wharton sold Matlack's bricks. By the mid 1850s, Wharton began to buy stock in a zinc operation near Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, which was the first of his business adventures that resulted in large fortunes.

In 1854, Wharton was persuaded to become the manager of the Pennsylvania and Lehigh Zinc Company. Wharton revolutionized the zinc industry by creating the Pennsylvania and Lehigh Zinc Company Spelter works, which became the first commercially successful plant in the United States for manufacturing metallic zinc. The demand and price of zinc rose from six and one fourth to 15 cents a pound. Wharton put $40,000 worth of profits into U.S. bonds. He cut his ties with the Lehigh Zinc Company in 1863 when he was worth approximately $200,000. After zinc, Wharton ventured into nickel ore, forming the American Nickel Works and spreading his operation throughout the Delaware, Lehigh and Saucon Valleys with nickel mines and smelting plants. At the same time, Wharton sat on the board of directors of the Bethlehem Iron Company. Under Wharton's direction, they later formed the Bethlehem Steel Company. By the late 1870s, Wharton made several million dollars from his nickel business. He used this money to increase his interest in the Bethlehem Steel Company.

In 1899, as the largest stockholder in the Bethlehem Steel Company, Wharton negotiated the sale of the company to the Schwab family. Earlier in the decade and throughout the 1880s, Wharton began to invest in gold mines in Nevada and mining and refining operations in New Jersey. In 1902, Wharton ended his nickel adventures when he sold his refining works in Nickel Mines, Pennsylvania and American Nickel Works in Camden, New Jersey to an enterprise called International Nickel Company. He was given a seat on the International Nickel Company's board of directors. However, when he sold his most lucrative business, Wharton had already diversified his business investments. He bought large amounts of southern New Jersey property, a menhaden (a type of fish similar to herring) processing factory that produced fertilizer, and a forestry planting operation. He dreamed of solving Philadelphia's water problem with an intricate system of canal works, but the South Jersey Water Company never formed. Wharton was an extremely skilled and successful business man, but he did not let that distract him from his Quaker beliefs and family obligations. Ultimately, Wharton was a man who remained active in philanthropy, entrepreneurship, international commerce, and politics up until his death in 1909.

In 1854, Joseph Wharton married Anna Corbit Lovering, and the couple had a daughter named Joanna. When Wharton took the job as manager of Bethlehem Iron, living arrangements became problematic for the young couple, and Wharton lived alone in Bethlehem while Anna took care of Joanna in Philadelphia. Anna later came to live with Wharton in Bethlehem until he sold his interests in his zinc business and returned to Philadelphia. In the 1870s, Wharton built a large estate in New Jersey named "Bellevue," due to the numerous cases of typhoid that took place in Philadelphia because of bad water treatment. Wharton also built a large home near Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island in the 1880s, which he called "Marbella." This is where he and his family vacationed in the summertime. Wharton was also a guardian and mentor to many young people, particularly to a group of brothers by the name of Thurston. Wharton took care of them and watched as they too ventured into the business world.

Wharton not only created opportunities for underprivileged boys and jobs for countless people, he also created a lasting legacy. The Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania is probably the most memorable and lasting of Wharton's contributions. Wharton wrote many papers on international industrial competition. In one speech, Wharton illustrated the deficiencies and issues of American commerce throughout the world. Wharton decided to endow the University of Pennsylvania with $100,000 to establish a School of Finance and Economy to better assist students in their business careers. Wharton initially intended for the school to teach economic protection of American interests' globally, the same issues he had labored for in Washington over protective tariffs; however, the Wharton School of Business grew to develop political and social sciences. The teaching of social and political science merged with the teaching of commerce and finance, creating one of the most prominent business schools in the world to this day.

Joseph Wharton left a legacy with a school that bore his name, but he helped create what has become one of the most prominent liberal arts colleges in the country. In 1869, Wharton and his mother, along with other Quakers, founded Swarthmore College in Delaware County, Pennsylvania. The college was meant to give both boys and girls the highest forms of education without religious influence. Unlike Wharton's biggest competitor Andrew Carnegie and his Gospel of Wealth, it was Wharton's religious Quakerism that encouraged his philanthropy. Until his death on January 11, 1909, Joseph Wharton was the type of man who never neglected his roots. He understood Philadelphia was where he got his start and he looked to help the city in times of need. Wharton understood that to fix the problems with American international industry he had to better educate the students of commerce and finance.

- International Industrial Competition: A Paper Read Before the American Social Science Association, at their General Meeting in Philadelphia, October 27, 1870. Philadelphia: Braid, 1872.

- Mexico. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1902.

- Garn, Andrew. Bethlehem Steel. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1999.

- Sass, Steven A. The Pragmatic Imagination: a History of the Wharton School, 1881-198. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 1982.

- Yates, W. Ross. Joseph Wharton: Quaker Industrial Pioneer. Bethlehem: Lehigh UP, 1987.

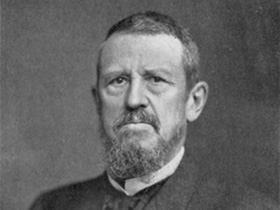

Photo Credit: "Joseph Wharton." 1902. Photography. Licensed under Public Domain. cropped to 4x3. Source: Wikimedia.