You are here

9/17/1883 - 3/4/1963

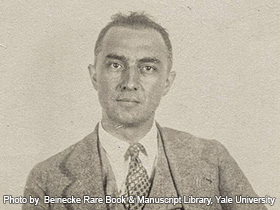

Pulitzer Prize winner and two-time Poet Laureate William Carlos Williams earned his medical degree at the University of Pennsylvania.

Pulitzer Prize winner and two-time Poet Laureate, William Carlos Williams earned his medical degree at the University of Pennsylvania. Read more here.

Wganer-Martin, Linda. Williams, William Carlos: (17 September 1883-04 March 1963). American National Biography. February 2000. 9 November 2018.

William Carlos Williams was born to immigrant parents in Rutherford, New Jersey, on September 17, 1883. His father, William George, was British and had lived most of his life in the Virgin Islands, and his mother, Raquel, was Puerto Rican. William Carlos grew up with his parents, brother, his paternal grandmother, and his uncles. This upbringing greatly influenced his writing style later in life, which was made apparent when Williams wrote, "Of mixed ancestry, I felt from earliest childhood that America was the only home I could ever possibly call my own. I felt it was expressly founded for me, personally."

In his teenage years, Williams ventured to Europe with his mother and brother for two years, studying in Switzerland and France. They attended the Château de Lancy near Geneva and the Lycée Condorcet in Paris. Following Williams's return to the United States in 1899, his father insisted that he attend Horace Mann High School. While at Horace Mann, William developed his passion for poetry.

At the age of 19, Williams entered the University of Pennsylvania's School of Medicine in Philadelphia. His choice to attend medical school was largely attributed to his middle namesake, his mother's older brother Carlos. Carlos helped raise Raquel and was a physician.

While at medical school, Williams met and befriended both Ezra Pound and Hilda Doolittle. Pound played an important role in Williams's development as a writer, serving as a contemporary fellow poet that was just as passionate about literature. Ezra invited Williams to the party where he met Hilda Doolittle (H.D.), who was attending Bryn Mawr College. Because Pound and H.D. were a couple, Williams never acted on his feelings, but is quoted as having admitted to his brother in To All Gentleness that "I'm dead in love with that girl."

Following his graduation from the University of Pennsylvania's School of Medicine in 1906, Williams moved to New York City to work as an intern at French Hospital. For two years he worked grueling hours before transferring to Nursery and Child's Hospital. In 1909, his first play, Betty Putnam, was produced. Then, he took a collection of poems to a local printer. Poems by William C. Williams only sold four copies, but it did earn him a review in the Rutherford American in May 6, 1909.

Williams began to date Charlotte Herman, as did his brother Edgar. The two brothers squabbled over the attractive girl until Edgar asked her to marry him, and she agreed. William Carlos locked himself in his room until he realized that he should marry Charlotte's sister, Florence. Florence agreed to marry Williams after he returned from the University of Leipzig where he was to study pediatrics. While in Germany, Williams made trips to see Ezra Pound in London and made other trips to visit his brother in Italy. After studying for a year, Williams returned to America, desiring to reconnect with Florence and establish his medical practice. In September 1910, Williams opened his practice in Rutherford, New Jersey. Three years after proposing to Florence, Williams married Florence on December 12, 1912, and the couple moved next door to his parents.

Soon after being married, Florence sent a group of Williams's poems to Poetry, a magazine from Chicago, and they were subsequently published. Pound was impressed by Williams's growth in his writing, so much so that he arranged the publication of Williams's The Tempers, which was published in 1913.

Williams moved his practice to his home in Rutherford, where it began to flourish. Shortly thereafter Florence became pregnant with the couple's first child, William Eric Williams, who was born on January 7, 1914.

Williams frequented New York City, exposing himself to the Greenwich Village crowd. In July 1916, Williams wrote "The Great Figure" while walking down 15th Street, inspired by a fire engine rushing past. In 1928, "The Great Figure" inspired the famous painting "The Figure 5 in Gold" by Charles Demuth, which is housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Demuth had known Williams when they both studied in Philadelphia and remained friends throughout their lives. The painting is one in the group of "poster portraits" that Demuth painted of his friends, using the number five as a symbol repeated in a random arrangement.

Williams began spending time at Grantwood in New Jersey. He and other poets worked on their crafts there. In 1916, he edited an episode of The Others, a poetry magazine based in Grantwood. He became friends with Marianne Moore, who had very much in common with him, since she had studied biology in college. Williams continued to be involved in Grantwood and The Others until the magazine failed due to funding shortages in the twenties. The group disbanded shortly after.

His second son, Paul Herman Williams, was born on September 13, 1916. In 1917, Williams's third volume of poetry, entitled Al Que Quiere!, was published. The poems widely reflected life in Rutherford, including townspeople and nature. Immediately following Al Que Quiere!, Williams began writing his next collection, which was entitled Kora in Hell. This collection was penned as a positive response to the engagement of United States forces in World War I. Although he did not serve, he was passionately in favor of the war.

Williams watched his father slowly die of cancer in the winter of 1918. On Christmas Day, Williams sat by his father's bed, only to be called away on an emergency. While he was on the call, his father passed away, forever leaving Williams with doubts and questions. "The Clouds" was a poem Williams wrote about his father and the circumstances surrounding his death. Within two years of his father's passing, he was again struck with loss when his paternal grandmother Emily Wellcome died of a stroke. Following these sorrow-filled events, Williams released Sour Grapes in 1921. The poems in the anthology are melancholy in imagery as well as meaning, filling the pages with the inadequacies of his life or circumstances. Furthermore, he was largely unhappy in his marriage and was seeing another woman that lived nearby.

Williams frequented Greenwich Village on the weekends, trying to find a new writer and friend that could take the place of friends whom had left for Europe in the previous years including Pound, H.D., and others. Williams met Robert McAlmon in July 1920. McAlmon recommended that they publish their own poetry magazine. They began to print Contact, a magazine featuring poems by Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, Pound, and James Joyce. The magazine ended after eight months when McAlmon met Bryher and H.D., agreeing to marry Bryher as a marriage of convenience. This allowed the two women to live together without facing public scrutiny. McAlmon moved to Europe with H.D. and Bryher.

Williams turned to Moore and Kenneth Burke after McAlmon's departure. While McAlmon and Pound began to insist that Williams travel to Europe, he wrote two books about America and all of its attributes. The Great American Novel was written in prose. According to Linda Wagner in William Carlos Williams' "The Great American Novel, "Williams had noted that the novel was 'a travesty on what I considered conventional American writing. People were always talking about the Great American Novel so I thought I'd write it.'" Wagner disagrees with his statement, mentioning the honesty present in his writing. She also notes the cyclical structure and its "feeling of urgency" lend to the dynamics of the work.

Williams's second book that year was Spring and All. According to poet and critic John Hollander, in Vision and Resonance: Two Senses of Poetic Form, Spring and All is "a poem of discovery, of the gradual emergence of the sense of spring from what looks otherwise like a disease of winter." According to Cheryl Wittenauer, "The Red Wheelbarrow" is Williams's most anthologized poem, which appears in Spring and All.

The Red Wheelbarrow

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens

This poem his well regarded by poets and critics. Pulitzer Prize winning poet and critic Robert Penn Warren and critic Cleanth Brooks said in their book, Understanding Poetry, that "reading this poem [The Red Wheelbarrow] is like peering at an ordinary object through a pin prick in a piece of cardboard. The fact that the tiny hole arbitrarily frames the object endows it with an exciting freshness that seems to hover on the verge of revelation."

Following the publication of Spring and All, Williams and his wife lived in Manhattan for six months, while Williams worked on In the American Grain. This work was based on American history and his interpretation of it, which included the incorporation of many heroes like George Washington, Ponce de Leon, and Christopher Columbus.

After their six month stay in Manhattan, Williams and Florence traveled to Paris for a six month visit because of Pound and McAlmon's encouragement. Williams he enjoyed himself, but he grew homesick. In To All Gentleness: William Carlos Williams, the Doctor Poet, Williams is quoted saying, "I am not of this clubÄü?I can never be at home here."

Williams and Florence returned to Rutherford, and he quickly began work on his next book. He had already written about the countryside and had witnessed the rapid expansion of cities. Realizing cities' importance, he decided to focus on them for his next book. He chose nearby Paterson, New Jersey, since he already had spent time there and was familiar with it. Williams then set out to write what some consider his most famous work, Paterson. It is written in prose and was published as five separate books, with a partial sixth volume. They were published separately in 1946, 1948, 1949, 1951 and 1958. According to Whittemore on Poetryfoundation.org, the central image in Paterson is "the image of the city as a man, a man lying on his side peopling the place with his thoughts."

In 1927, Williams founded another medical office in Passaic, New Jersey, which is near Paterson. He kept the office open for five years, despite customers paying him in vegetables, poultry, and home-brewed alcoholic beverages. That same year Florence and their two children ventured to Europe for schooling, giving Williams plenty of time to himself for writing. He escorted his family to Europe and stopped in Paris.

On the boat ride back from Europe, Williams began to write the series of poems titled The Descent of Winter. When he arrived home, he quickly picked up working on Paterson again. Also, Williams met Louis Zukofsky through Pound, and he and Williams became close friends. Zukofsky became his personal editor.

Williams began to write White Mule in honor of his beloved wife Florence and her family. The title came from "White Mule" whiskey because the Herman women where spirited and strong. It was a biography about an immigrant family that had to assimilate into American culture. White Mule became the first in a three book series about the Hermans, which included In the Money and The Build-up. He finished the series in the 1950s.

In 1941, American expatriate Ezra Pound made radio broadcasts criticizing the United States and glorifying Mussolini and Hitler. During the broadcast, he mentioned that Williams would understand what he was talking about. FBI agents were soon at Williams's door, questioning his loyalty to America. Since Williams had spent much of his career writing about America's greatness, he was offended by this question. He answered that he was of course a proud American. Pound was indicted for treason for his radio comments. The two friends became estranged until 1947, which is when Williams went to visit Pound, who was institutionalized at St. Elizabeth's Mental Hospital.

Williams began to fantasize of retiring and passing on his medical practice to his son William Eric, who was approaching graduation from medical school. In February of 1948, Williams suffered a heart attack. He began to write is Autobiography while he was in the hospital recuperating. Williams's mother, Raquel, passed away in 1949, at the age of 102, which greatly upset him. In 1950, he finally retired, leaving his practice to his son. Williams became restless and began to lecture at many universities, hoping to inspire the next generation of American poets.

In 1948, Williams began to receive accolades for his work. He received the Russell Loines Award from the National Institute of Arts and Letters and Honorary degrees from the Rutgers University, the University of Buffalo, and Bard College. In 1950, Williams received the National Book Award's Gold Medal for Poetry for Paterson III and Selected Poems. In March 1951, Williams had a stroke. Williams's writing became melancholy. The Library of Congress in Washington offered him a position as Consultant in Poetry. A month prior to his term at the Library of Congress, Williams suffered a second stroke that robbed him of his use of the upper right side of his body, speech, and vision. His vision returned slowly. He continued to write using an electric typewriter with his left hand. The Library of Congress took away his position, citing health reasons. Their the actual reason, however, was that McCarthyism was plaguing America, and Williams's association with Pound was held against him. The Library reinstated his position a month before the end on the term.

Williams grew depressed after his strokes, so he was admitted to Hillside Hospital in February 1953. Williams struggled with issues including: being distant from his children while they were growing up, whether or not his poetry was valued by others, and his many instances of infidelity. He wrote a letter to Florence telling her of his infidelities and begged her forgiveness, which she gave willingly. Around this time, Williams wrote "Asphodel." He used a triadic form that he called a "variable foot," according to Cary Nelson in Anthology of Modern American Poetry.

Williams left the hospital with waning health, and he retired to his home in Rutherford. He continued to write and completed Pictures from Breughel. In 1958, Williams found himself face to face with Pound for the last time. Pound had been released from St. Elizabeth's and set sail for Italy the following day.

Williams continued Paterson in 1961. He had rough sketches of Book VI, which never was completed. Williams spent most of his time with his beloved grandchildren, whom he wrote many poems for. In 1962, his final book, Pictures from Breughel, was published. This book was his 48th book.

Shortly before he died, Williams was disoriented and was unable to read or speak clearly. He celebrated his 50th anniversary with Florence in December 1962. He died on March 4, 1963, due to a cerebral hemorrhage he had in his sleep at his home. Williams was posthumously awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry for Pictures from Brueghel and the National Institute of Arts and Letters Gold Medal for Poetry.

"But everything in our lives, if it is sufficiently authentic to our lives and touches us deeply enough with a certain amount of feeling, is capable of being organized into a form which can be a poem."---William Carlos Williams in a personal note to his wife Florence as presented in To All Gentleness by Neil Baldwin

Book of Poetry:

- Kora in Hell. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1920

- The Great American Novel. Los Angeles: Green Integer, 1923.

- Spring and All. Frontier Press. 1923.

- Autobiography. New York: Random House, 1951.

- Pictures from Brueghel. New York: New Directions, 1962.

- Paterson. New York: Catedra, 2001.

- Imaginations. New York: New Directions, 1970.

- Baldwin, Neil. To All Gentleness: William Carlos Williams, The Doctor Poet. New York: Atheneum, 1984.

- Beach, Christopher. "William Carlos Williams and the Modernist American Scene." The Cambridge Introduction to Twentieth-Century American Poetry. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 2003.

- Brooks, Cleanth and Robert Penn Warren. Understanding Poetry. 4th ed. New York: Holt, Rinehart, Winston, 1976.

- Eisman, Alvord L. "Charles Demuth." Biography. 1982. 19 May 2007. <>http://www.answers.com/topic/charles-demuth>.

- Hollander, John. Vision and Resonance: Two Senses of Poetic Form. 1975. Modern American Poetry. University of Illinois. 12 May 2007. <>http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/s_z/williams/spring.htm>. Nelson, Cary, ed. "William Carlos Williams (1883-1963)." Anthology of Modern American Poetry. New York: Oxford UP, 2000.

- Poetry Foundation. "Archive: William Carlos Williams (1883-1963)." 2007. 18 May 2007. <>http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/william-carlos-williams>.

- Reuben, Paul P. "William Carlos Williams." Perspectives in American Literature. 31 Mar. 2007. California State University-Stanislaus. 16 May 2007. <>http://web.csustan.edu/english/reuben/pal/chap7/wcw.html>.

- Wagner, Linda Welshimer. "William Carlos Williams': The Great American Novel." NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction 3.1 (Autumn 1969): 48-61.

- Wellner, Anita. "William Carlos Williams Collection." University of Delaware Library: Special Collections Department. July 1993. 17 May 2007. <>http://www.lib.udel.edu/ud/spec/findaids/willi_wc.htm>.

- "William Carlos Williams." Poets.org. 2007. Academy of American Poets. 15 May 2007. <>http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/119>.

- Wittenauer, Cheryl. "William Carlos Williams Manuscript Donated to Southeast." 5 Mar. 2007. 16 May 2007. <>http://www.semo.edu/news/index_13230.htm>.

Photo Credit: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University. "Photograph of William Carlos Williams." c. 1920. Photograph. Licensed under Public Domain. Cropped to 4x3. Source: Wikimedia.