Few phrases in American history are more famous than the preambles of the Declaration of Independence and of the U.S. Constitution. The Declaration begins: “When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.” These powerful words resonate throughout our country’s history and are enacted into law by the words of the Constitution: “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

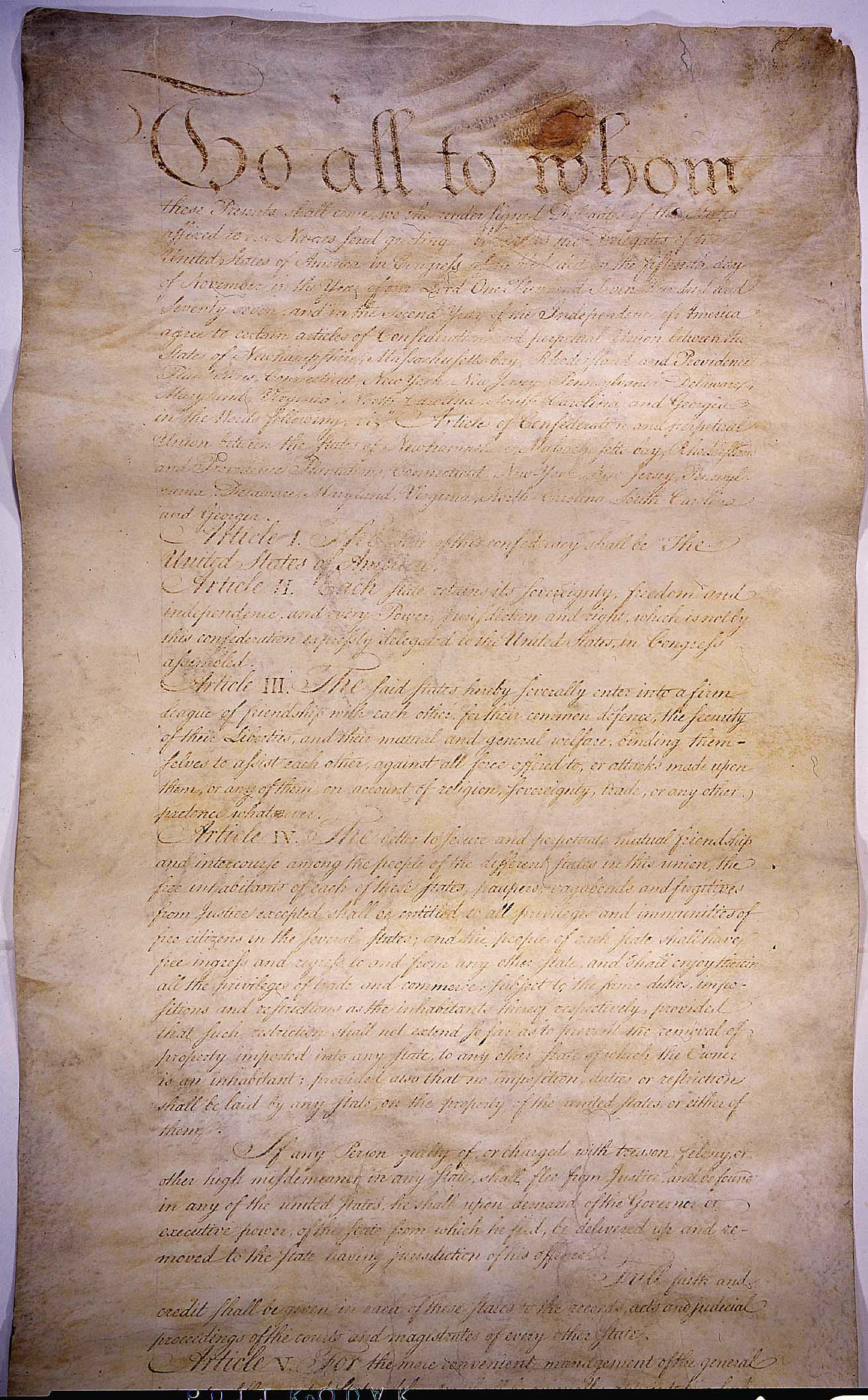

But what can be said of the preamble to the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union? “To all whom these Presents shall come, we the undersigned Delegates of the States affixed to our Names send greeting.” This phrase certainly doesn’t carry the same power, authority or historical significance of the other preambles, but it is symbolic of the troubles the United States faced under the Articles of Confederation. While it would take the Founding Fathers a second try to produce what would become the U.S. Constitution, the Articles laid an important foundation for the establishment of our nation.

During the 1760s and early 1770s, the American colonies found it ever more difficult to abide by British policies, especially those concerning taxes and the western frontier. The French and Indian War had left the British Empire with a government breaking £133 million debt in 1763, and the ministers and members of the British Parliament felt that the colonies were obligated to assist in reducing this balance. Various Acts were passed by Parliament in an attempt to raise revenue and bolster British trade, but they were met with stiff resistance from the colonists.

Multiple protests—such as the Boston Tea Party—were organized in an attempt to influence British policies but instead resulted in the closing of the port in Boston and the declaration of martial law in Massachusetts. In response to British actions, the First Continental Congress met in Carpenter’s Hall in Philadelphia from September 5 to October 26 of 1774, with representatives from twelve of the thirteen colonies, to coordinate a colonial boycott of British goods. However, as fighting between the British and colonists erupted at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, the Second Continental Congress turned its attention to coordinating resistance efforts. British authority continued to be challenged throughout the colonies, but many colonists hoped that the differences between the two sides could be resolved.

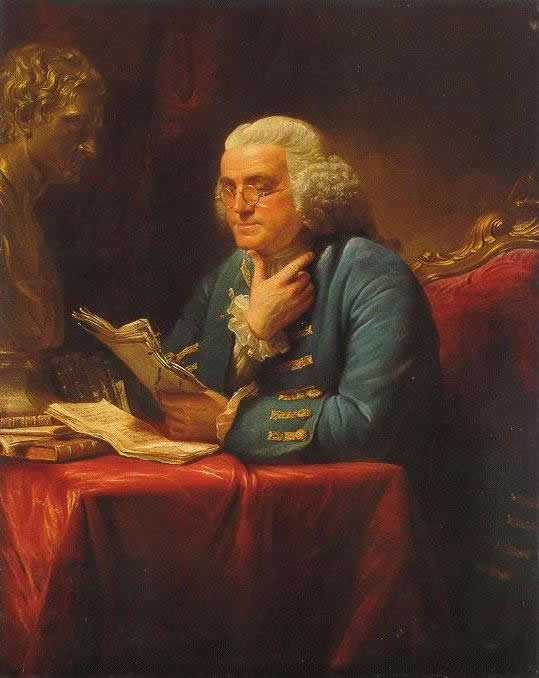

However, on December 12, 1775, Pennsylvanian Benjamin Franklin, an active member of the Secret Committee of Correspondence, sent a letter to a prince of the Spanish royal family to speak of the advantages an alliance with the colonies could provide. He also sent a copy of this letter to American supporters in France, hoping to find aid for the colonies. Meanwhile, the British Parliament continued to make life difficult for the colonists by prohibiting trade with the colonies, prompting Thomas Paine’s call for a declaration of independence from Great Britain:

nothing can settle our affairs so expeditiously as an open and determined declaration for independence… Were a manifesto to be published and dispatched to foreign courts, setting forth the miseries we have endured, and the peaceful methods which we have ineffectually used for redress; declaring at the same time, that not being able, any longer, to live happily or safely under the cruel deposition of the British court, we had been driven to the necessity of breaking off all connection with her; at the same time, assuring all such courts of our peaceable disposition towards them, and of our desire of entering into trade with them. Such a memorial would produce more good effects to this continent than if a ship were freighted with petitions to Britain.

This excerpt from Paine’s famous essay Common Sense was published and distributed throughout the colonies in January 1776. In Common Sense, Paine creates an argument which calls for a colonial declaration of independence from Great Britain. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a motion in the Second Continental Congress to fulfill Paine’s call for independence. A draft of the Declaration of Independence was then written and signed on July 2, 1776, though we have come to celebrate the occurrence on July 4.

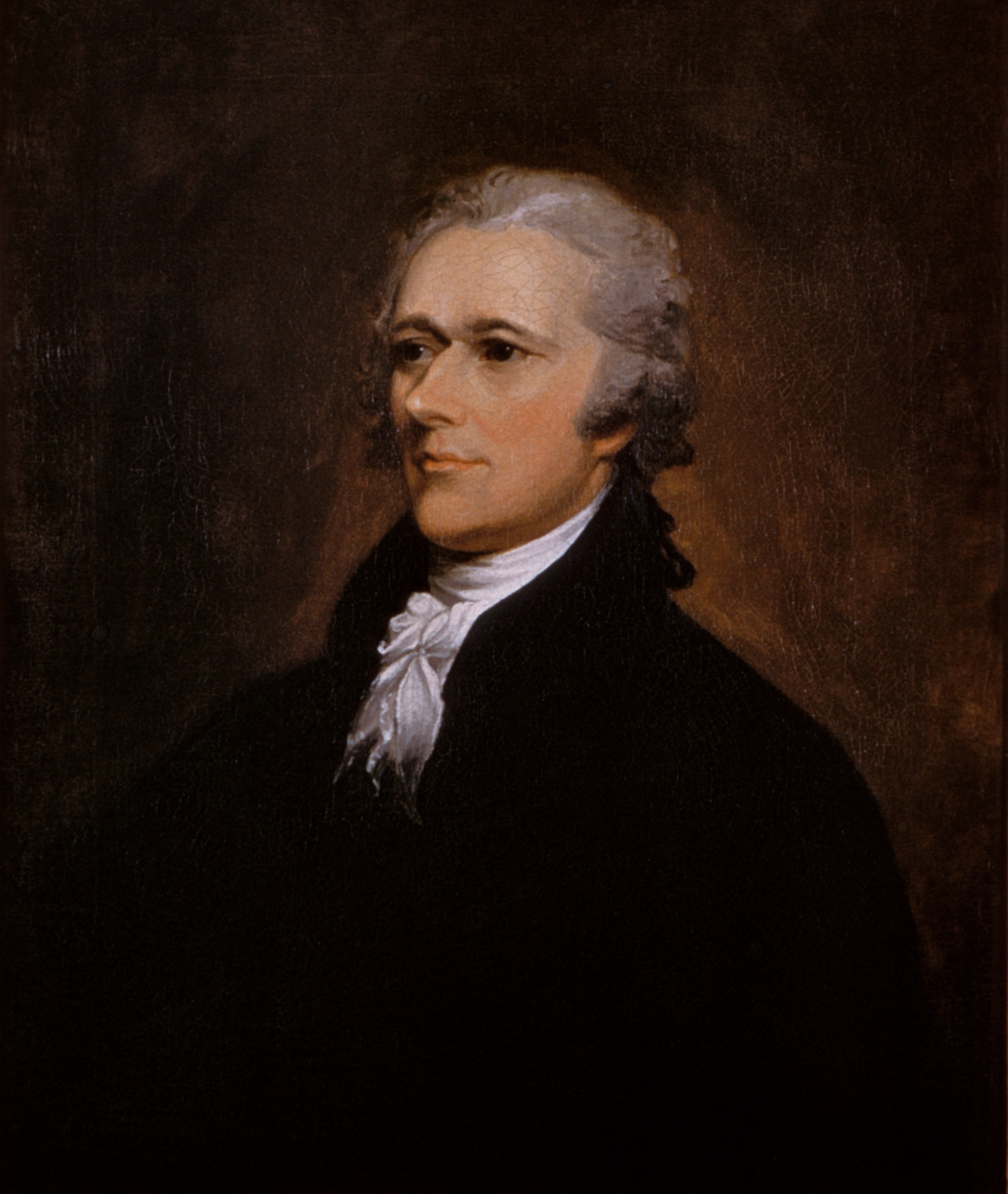

Following the creation of the Declaration of Independence, the Continental Congress realized that a governing document would need to be created that would unite the colonies and provide a legal framework for governmental development within the new Union. A committee from the Continental Congress was established to generate this document under the leadership of Pennsylvanian John Dickinson. Discussions began on July 22, and debate soon ensued over a number of issues that had been plaguing the colonies including taxation, the power distribution between a central government and independent states, interstate relations, western land claims, and state representation in the national government. Much of this debate was sparked by the fear of creating the same tyranny within the colonies that was present in Great Britain. Two schools of thought developed that shaped these debates; one in favor of a strong central government and one in favor of a weak central government. Amongst those in favor of a strong central government were Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay. On the other end of the spectrum was Thomas Jefferson. These discussions continued into late autumn, with ideology of the anti-federalists setting the framework for a majority of the laws written in this document.

An initial draft of this document, known as The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, was completed and first approved for ratification by Congress on November 15, 1777 in York, Pennsylvania. Virginia was the first state to ratify the Articles on December, 16, 1777, while eleven other states signed it during the following two years. However, due to disputes over western land claims, Maryland refused to ratify the Articles. It wasn’t until Virginia surrendered its claim on land in the Ohio Valley, that Maryland signed the Articles. They were finally promulgated on March 1, 1781. The final copy contained thirteen articles that attempted to address the issues facing the colonists in the midst of the Revolutionary War.

In Articles I and II, Congress establishes the colonies as “The United States of America” and affirms that each state would retain its sovereignty, freedom, independence, jurisdiction and any right not granted to Congress.

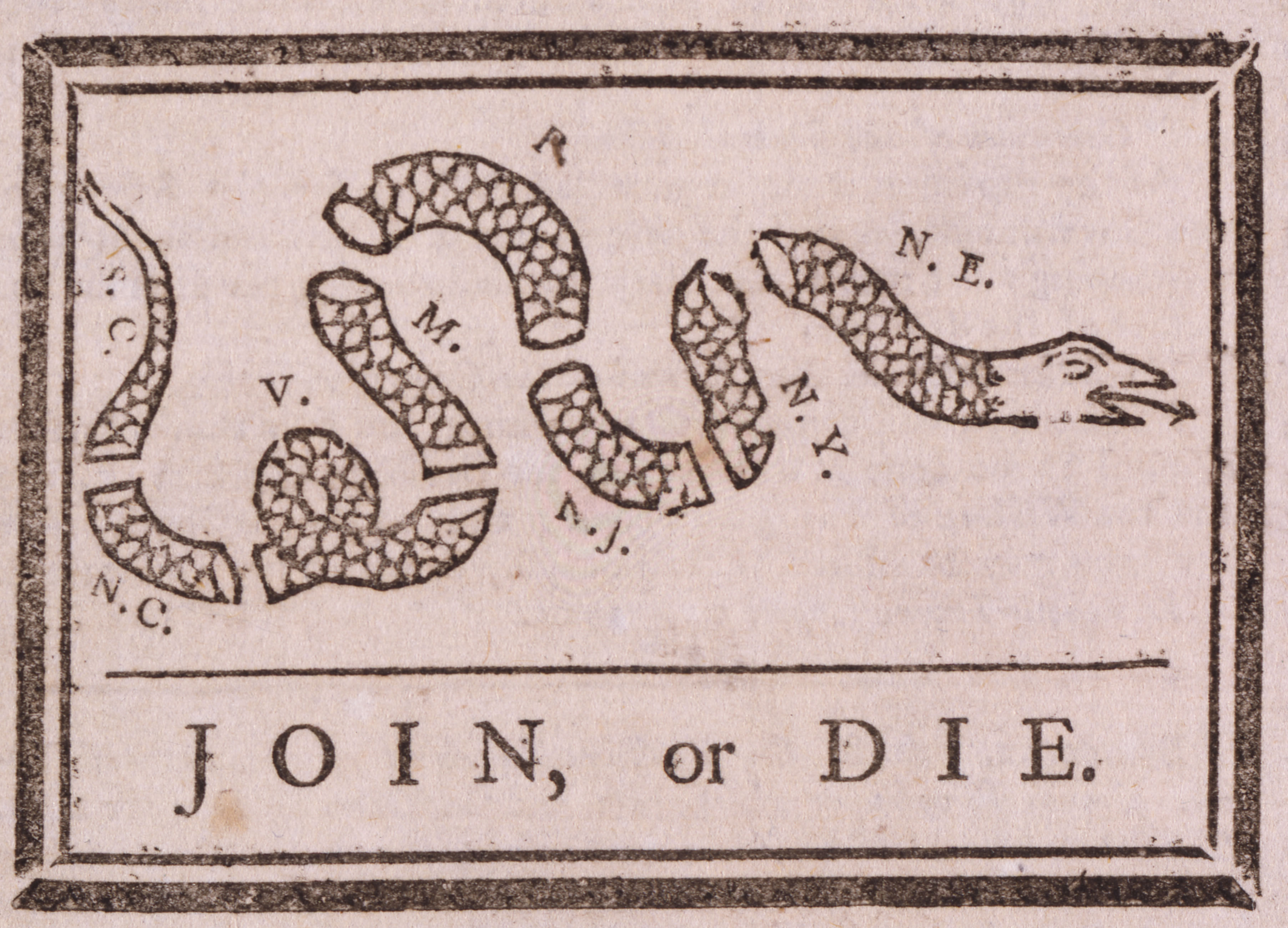

This wasn’t the first time that the colonies had experimented with a united government. In 1754, the British government called for a meeting between the New York colony, the Mohawk nation, a part of the Iroquois Confederation. The meeting was planned to discuss colonial-Indian relations; however, another meeting known as the Albany Congress also took place during this time. It was here in the meeting between the colonies that the Albany Plan, written by Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Hutchinson, was first discussed. The plan called for uniting the colonies under a centralized government that would provide for better relations between the colonies, and also unite them in preparation for the imminent French and Indian War.

While the Albany Plan was eventually rejected by the States for fear of losing too many of their rights, it did provide an outline of the benefits a union between the States could offer. Many of the ideas presented in the Albany Plan were used to write the Articles of Confederation, some of which are mentioned in Articles III and IV. In these articles the states agree to enter into a firm “friendship” with each other for their common defense, to protect their freedom, and their mutual and general welfare. Each State agreed that it would defend the other from any attack on account of religion, sovereignty, trade or any other pretense. To ensure the friendship between all the States, free inhabitants of each state would be granted the same rights as a person living in any other State. If any person were charged with a crime and was found, he would be returned to the State in which the crime was committed. The Full Faith and Credit Clause is also first seen here in Article IV and states that the records, acts, and judicial proceedings of one State will be recognized by the other States. However, this issue would again be revisited.

Key to the argument of central versus state government was the decision of how many representatives and votes to allow each State in Congress. On October 7, 1777, the Continental Congress put to vote this very issue. Two proposals suggested that votes be determined by the number of white inhabitants in each State and another suggested that the number of votes be determined by the proportion of a State’s contribution to the tax revenue of the national treasury. None of these proposals were approved by the Congress. Each State instead was granted a single vote in Congress regardless of its size and this was recorded in Article V.

Article V states that each State would appoint its legislators before Congress’ annual meeting on the first Monday in November and they had the right to recall their delegates and replace them with others for the remainder of the year. No State would be represented by less than two, or more than seven members. No representative could serve more than three years in a six year period and could not receive any payments or benefits for another position he held in the United States government. Each state would have one vote in Congress regardless of how many representatives it sent. The delegates freedom of speech would be protected while they served in Congress. They would also be protected from arrests and imprisonment while in Congress unless they committed treason, a felony, or breach of the peace.

Fully aware of the problems created by a monarchial form of government, the writers of the Articles of Confederation knew that the new democratic government would have to avoid the titles and hereditary powers granted by a King. Such a form of government granted elite individuals too much power while the common citizen was left helpless to their rulings. These preventative measures were added in Article VI. In Common Sense, Thomas Paine writes:

In England, a king hath little more to do than to make war and give away places; which, in the plain terms, is to impoverish the nation and set it together by the ears. A pretty business, indeed, for a man to be allowed eight hundred thousand sterling a year for, and worshiped into the bargain. Of more worth is one honest man to society, and in the sight of God, than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.

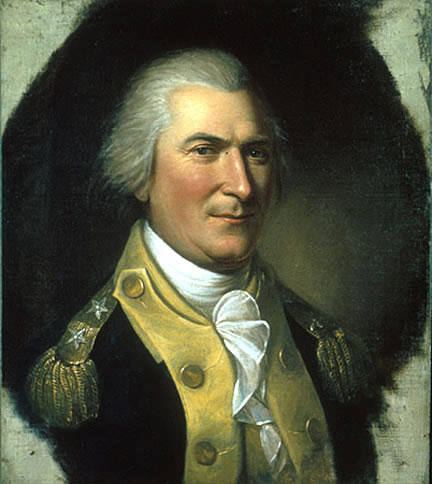

Paine’s feelings must have been reflective of the colonialists’ and Article VI assures that the United States could avoid the problems created by a King. However, it’s interesting to note that after the Revolutionary War some men wanted to name George Washington King of the United States. When King George III asked his American painter what Washington would do after the war, that painter, Pennsylvania native Benjamin West, replied “They say he will return to his farm.” The King replied, “If he does that, he will be the greatest man in the world.” Washington’s refusal to accept the kingship permanently removed the notion that there would ever be a monarch in the United States.

This Article also requires the States to be on guard and have well regulated militias ready for defense. Article VI stated: No State would be allowed to send ambassadors to a foreign country, receive foreign ambassadors, or enter into any agreement with a King, Prince or foreign State. No person living in a State would accept any present, office or title of any kind from any King, Price or foreign State. Neither Congress nor the States would be allowed to grant a title of nobility. No two States would be allowed to enter into a treaty with each other unless approved by Congress. No State would interfere with any treaties made by Congress with any King, Price or foreign State. No State would be allowed to maintain warships or a military in a time of peace unless approved by Congress for self-defense. However, each state should maintain a well-regulated and disciplined militia that is sufficiently armed and accoutered. No State could engage in a war without the consent of Congress unless the danger is so imminent that permission from Congress could not be obtained.

Article VII also refers to State’s ability to prepare their armies for the common defense. It reads that when land forces are to be raised by any State for the common defense, all officers of or under the rank of colonel would be appointed by the legislature of each State to lead the troops. The British, Spanish, and Native Americans all presented potential threats to the well being of the colonists and they needed to be prepared to defend themselves from any attack.

While common defense was extremely important to the States, they needed to establish a plan to pay for this defense. One of the most famous cries throughout the American Revolution was “No taxation without representation!” The debt from the Revolutionary War was quickly accruing as the Articles were written; however, those in favor of a strong state government felt that the national government had little right to collect additional taxes to those of the States.

Article VIII states that all expenses incurred for the common defense of the country would be defrayed from a common treasury when allowed by Congress. Each State would be responsible for contributing to the common treasury based on the value of land within that State. Congress would determine the method of surveying the land and would appoint the time of the survey. These taxes would be collected by the legislatures of the several states in a time agreed upon by Congress. Unfortunately the language of this Article would deny Congress the ability to collect taxes; they were merely able to “ask” the States to collect taxes periodically. This issue would cause future problems for the young nation, and would be revisited during the Constitutional Convention.

The theme of limited power for the central government is continued in Article IX and it provides a list of the few powers granted to Congress. To avoid creating an overly powerful central government, the framers were extremely cautious with the powers they granted Congress and were sure to outline them carefully. Only Congress had the power to determine times of war and peace—except for the situations mentioned in Article VI—to send and receive ambassadors and to enter treaties and alliances with other nations. Congress would appoint courts for the trial of piracies and felonies on the high seas. Congress would assist in resolving issues concerning state boundary disputes, jurisdiction or any other cause but only as a last resort. Congress had the sole and exclusive right to regulate the alloy content and the value of coins created by Congress or the individual States and would determine the standards of weights and measures to facilitate the regulation. Congress would also manage all affairs with Indians who were not members of any State provided that the legislative right of any State was not infringed or violated. Congress would regulate the post offices throughout the States and could charge postage to defray the expense of the offices. They would appoint all officers of the army and navy and would commission all officers and determine the rules for the government and regulation of these forces and would direct their operations.

While this may seem like a thorough list of powers, it barely granted Congress the ability to run a national government. No judicial was branch established, Congress could merely appoint courts to rule over trials of piracy or felony and would serve as a judge for State boundary disputes but only as a last resort. Congress’ only legitimate form of taxation was through its ability to charge for postage which would defray the expenses of handling mail. The problem of multiple currencies is linked to this Article because there is no requirement of a uniform currency system for all of the colonies. The States had the right to produce their own currency but this compounded the problem and made it difficult to determine one currency’s value compared to another.

U.S. Army Center of Military History

The Congress was granted the power to create “A Committee of the States” which served in place of Congress when not in session. One delegate from each State would serve on the committee. Congress also had the power to create other government agencies that were needed to manage the affairs of the United States. Congress had the authority to appoint one of their members as president but he could only serve for one year, every three years. Congress had the ability to raise the amount of money needed for running the United States, could spend this money and borrow money on the credit of the United States. Congress could also raise an army and navy and request soldiers based on the proportion of white inhabitants in each State. Once the troops were raised, the States were responsible for appointing officers, equipping the troops and marching them to a designated place as determined by Congress.

It was under this Article that Pennsylvanians Elias Boudinot (though he represented New Jersey), Thomas Mifflin, and Arthur St. Clair were chosen to serve as “President of the United States in Congress Assembled.” Eight men held this position from 1781 to 1789 and were John Hanson, Elias Boudinot, Thomas Mifflin, Richard Henry Lee, John Hancock, Nathaniel Gorham, Arthur St. Clair and Cyrus Griffin. These men are not considered to be “Presidents” of the United States because of the little power that came with their position as compared to executive power that is granted to Presidents of the United States under the Constitution. While this Article may not grant Congress the power to lead a national government, it does lay the foundation for some of the corrections that would come in the U.S. Constitution.

The article concludes by stating that in order for Congress to act on the powers described above, nine of the thirteen States must be in agreement. Any other issues, except for the request to adjourn from day-to-day, must be decided by a majority vote. Congress also had the right to adjourn at any point during the year or move the meeting to another location; however, the adjournment must be no longer than six months. Congress would publish its proceedings monthly unless a matter of security would prevent such an action. The report would also include the voting patterns of the delegates and each delegate might obtain a copy of the report to present to their State legislature.

Article X states that the Committee of the States or any nine of them had the full authority to act while Congress was in recess. However, the Committee of the States could not exercise any power that required the consent of nine states while Congress was in session. Again, we see the fear of too much national power. While there was a need for a governing body that could replace Congress in its absence, the framers granted this body even less power than it gave to Congress.

National Park Service

Another important issue facing the colonies during the drafting of the Articles was establishing a plan to absorb new states into the Union. While it was still undetermined who would ultimately end up with possession of the western territory, the framers devised a plan to incorporate new States into the Union. Canada was also included in this Article because it was still under British rule during the Revolution but it was unknown if they would declare their independence as well. Article XI states that if Canada declared its independence and agreed to the terms of the confederation, it could join the United States and would be entitled to all the advantages of the Union. The offer would not be extended to any other colony unless agreed to by nine States.

The cost of the Revolutionary War was a pressing issue that the Continental Congress needed to address. Article XII states that the United States assumed all financial responsibility for debts accrued during the American Revolution and solemnly pledged to repay these debts. It was in this Article that the federalist philosophies of a strong central government were finally able to work their way into the Articles. However, due to Congress’ inability to collect taxes from the colonies, this Article would not be fulfilled and debt repaid until the 1800s.

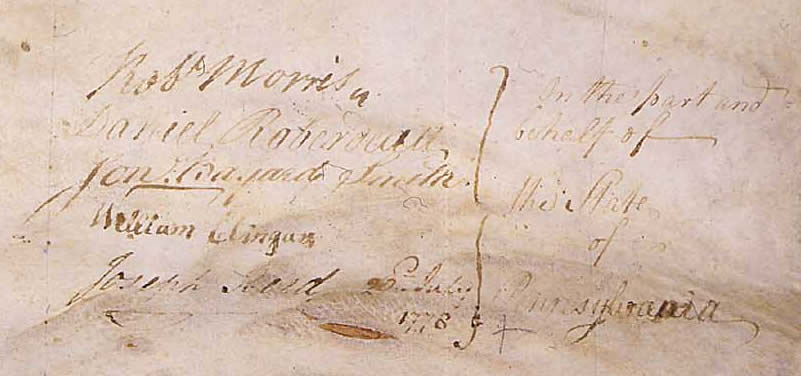

Article XIII closes out the Articles of Confederation and states that all of the States must follow the rules created by Congress. No alteration would be made at any time to the Articles unless agreed upon by Congress and then by the legislatures of every State. Each delegate who signed the Articles had the power to ratify them for their respective State. The States also agreed to inviolably observe the determinations of Congress and the Union would last forever. These Articles were written in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on July 9, 1778, in the third year of independence of America.

While writing the Articles of Confederation solved the problem of establishing a national government, the document did not grant the central government enough power to assure the continued successful development of the United States. Opinions of the new government ranged considerably, some questioned why the Revolutionary War was fought, but Jefferson’s opinion of the situation was, in all likelihood, shared by a majority of the colonists when he said “with all the imperfections of our present government, it is without comparison the best existing or that ever did exist.” He went on to say that when comparing the European governments and the United States, such a comparison “is like a comparison of heaven and hell.” Founding father John Jay shared this opinion and said “our federal government has imperfections, which time and more experience will, I hope, effectually remedy.” But what were the imperfections that caused the Articles of Confederation to be discarded and replaced by the Constitution?

The principal issues that caused the failure of the Articles were the inability of the federal government to levy taxes and the poor status of foreign and domestic trade. These issues were closely related and needed to be amended together. Trade between the States was inefficient and difficult as tariff wars raged, and multiple State currencies made value interpretation nearly impossible. Even though these were pressing issues, they certainly were not the only issues that needed to be addressed by the founding fathers. In his book The Framing of the Constitution, author Max Farrand writes:

There were some matters requiring greater uniformity of treatment and procedure than could be obtained from independent state action. Such were naturalization, bankruptcy, education, inventions, and copyright. Upon these subjects, accordingly, congress ought to be authorized to legislate. For somewhat different reasons other matters were just as clearly beyond the scope of state action and in these also the central government should be given power: To define and punish treason, to establish and exercise jurisdiction over a permanent seat of government, to hold and govern the western territory that had been ceded by the states, to provide for the establishment of new states and their admission to the union, to maintain and efficient postal service and, some said, to make internal improvements. If such fields of action were granted to the central government, the states would be free to exercise sufficient authority in local matters.

With these problems inadequately addressed in the Articles of Confederation, something had to be done quickly to preserve all that had been fought for before and during the Revolutionary War. However, it was Shay’s Rebellion in 1786 and 1787 that was the tipping point requiring immediate action and review of the Articles of Confederation. Led by Daniel Shay, a Revolutionary War hero, a group of 1,500 rebels or “Regulators” as they called themselves, sought to revolt against the government in Massachusetts for multiple reasons, including excessive property taxes, poll taxes, and the currency system. On August 29, 1786, Shay and his Regulators stormed the Northampton courthouse and stopped a debtors trial. On January 25, 1787, they stormed an arsenal in Springfield in what turned out to be the bloodiest clash of the rebellion. The rebellion ended after a majority of the Regulators surrendered; however, it did reveal the weakness of the State and National governments. On October 31, 1786, George Washington wrote “I am mortified beyond expression when I view the clouds that have spread over the brightest morn that ever dawned in any country… What a triumph for the advocates of despotism, to find that we are incapable of governing ourselves and that systems founded on the basis of equal liberty are merely ideal and fallacious.”

From May 25 to September 17 of 1787, the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia to correct the deficiencies created by the Articles of Confederation. It had been called for the “express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation” and to assure that they were “adequate to the exigencies of government, and the preservations of the Union.” Amongst the most important issues to resolve were taxation, state representation in the national government, and controlling interstate commerce. In the Federalist Papers, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay present an argument on the inefficiencies of the Articles through a series of essays to the state of New York, some of which include a discussion of these issues.

Congress’ inability to collect taxes from the colonies was the foremost issue and it created numerous problems for the developing nation including a rebellion and an inability to pay the soldiers who fought in the Revolutionary War. In The Federalist No.XXX, Hamilton writes:

Money is, with propriety, considered as the vital principle of the body pol