Taphephobia is the medical term for an unreasonable and persistent fear of being buried alive. Although today most people are more afraid of public speaking or heights than being mistaken for dead, during the middle and late 1700s, a bestselling book by a French physician on the subject caused many to think twice about their postmortem plans. Fearful readers took such drastic measures as adding a request to their wills for a three-day waiting period between death and burial so that signs of putrefaction could be observed. Although the majority of the horror stories of being buried alive can now easily be discounted as fiction, there were several cases of it actually occurring. Regardless, by the 1800s, many people were looking for novel ways to insure against premature burial. To answer these requests, the end of the nineteenth century saw the introduction of two practices, embalming and its less popular relative, cremation.

Although today cremation is a widespread, accepted alternative to burial, it was not always an option in the United States. In fact, amongst the conservative majority of the New World during the nineteenth century, the mere suggestion of cremation invited fear, disgust, and, occasionally, hostility. While many people can be given credit for mainstreaming the practice, the story of modern cremation in America began in the mid-1800s in a small Pennsylvania town thirty miles southwest of Pittsburgh and one man, Dr. Francis Julius LeMoyne.

Dr. Francis Julius LeMoyne was born on September 4, 1798 to Dr. John Julius LeMoyne and Nancy McCully in Washington, Pennsylvania. John Julius was a very busy man and at one point or another made a living as an innkeeper, a druggist, and a physician. In addition, as a lover of wild flowers and exotic birds, he also considered himself something of a naturalist. Francis J. LeMoyne spent his childhood observing his multi-talented father and would also wear many hats in his lifetime.

After graduating from Washington College, LeMoyne went on to have a very successful career as a medical doctor and apothecary, as well as, gain widespread recognition as a civil rights activist and pillar of the Washington community. By day, his home at 49 East Maiden Street appeared to serve merely as his medical office and drugstore, but Dr. LeMoyne would regularly open his home and other properties to escaping slaves on their way north aboard the Underground Railroad. In addition, LeMoyne was a strong advocate of education. The doctor helped start Citizen’s Library, Washington’s first free public library, and the Washington Female Seminary.

Eventually, the doctor’s years of helping others began to catch up with him. A victim of severe rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes, he was getting older and, according to Clay Kilgore, a historian employed by the Washington County Historical Society, by 1855 he began to scale down his medical practice to begin focusing more of his energy on medical research. One particular subject seemed to interest him more than any other-what should be done with the bodies of the dead.

The practice of embalming became popular during the American Civil War because it allowed for soldiers killed far from home during battle to be returned to their families and buried in their hometowns before decomposition set in. As many as forty thousand soldiers were embalmed during the war but, says Christine Quigley in The Corpse: A History, the embalming of Abraham Lincoln’s body for its long journey from the national capital to Illinois did the most for the industry. People were pleasantly surprised by the excellent condition the fallen soldiers and President remained in, even after several days. Though it does make the funeral easier to endure, unfortunately, embalming is not a permanent fix; it merely retards putrefaction. Sooner or later, corpses prepared in this matter begin to break down.

Dr. LeMoyne had begun to suspect that the current method of laying the dead to rest, embalming followed by inhumation, was actually having a detrimental effect on the health of his neighbors and friends in Washington. Many were falling victim to fatal diseases and he believed that the popular pine coffins used in his community were not capable of preventing the germ-ridden matter present in the bodies from escaping after burial. In fact, in a 2007 Observer-Reporter article by Scott Beveridge on Dr. LeMoyne, he is quoted as saying that burial was, “the most barbarous and disgusting method” of handling the dead. According to Fred Rosen, author of the book Cremation in America, he theorized that the ground water was running through these graves and contaminating the sources of water that the town used. At first, says Kilgore, LeMoyne believed that the ideal way to dispose of the body would be to leave it uncovered in the environment and allow nature to take its course. However, once he discovered the connection between the decomposing bodies and rampant illness in the community, LeMoyne settled on a new alternative to promote-cremation.

Initially, LeMoyne sought help from those he hoped to protect. He went to the trustees of Washington’s public cemetery and offered to fund the entire project if they would allow him to build a crematory on the cemetery’s land. Without hesitation, the trustees declined. Undeterred, the doctor began planning for the construction of the crematory on his own land, popularly known as Gallows Hill due to its brief history as an execution site.

LeMoyne enlisted the assistance of a fellow Washington resident, John Dye, to aid him in erecting the structure. According to the Washington County Historical Society, Dye drew inspiration from the first modern crematory, built by Frederick Siemens in Germany. LeMoyne himself designed a revolutionary oven in which the flames would never actually touch the body. The twenty by thirty foot building cost $1,500 and held a reception room and a smaller furnace room where the cremations would actually take place. “Everything was plain, repulsively so…. Just a practical corpse incinerator, as unaesthetic as a bake-oven,” wrote one visitor to the crematory closely following its completion in 1876 as quoted in the Observer-Reporter article.

In her biography of LeMoyne written in 1941, author Margaret McCulloch describes the furnace, “[it] was in structure a simple type of fire-clay retort such as is used in making illuminating gas, and in appearance, merely a large brick furnace with a metal door provided with a small opening for observation…. An iron crib was constructed for the body to be placed on and lifted into the furnace.” No bigger than necessary, the furnace is ten feet long by six feet high and six feet wide. Clay Kilgore explains that LeMoyne called for two iron doors to be built just in case the first one warped due to the heat. Closing the door was much like “closing a submarine hatch”; one would just spin the handle to tighten the hold against the door. To aid in monitoring the body during the actual cremation, a small peep-hole was placed in the door. At first, the furnace was heated using coal and later a pipe was added to allow heat by gas. LeMoyne used dead sheep from his farm to test his creation.

Besides providing an excellent venue for a funeral, says Kilgore, the reception room held a long, sturdy table used to prepare the body for cremation. Among other things, preparation would include wrapping the body in a linen sheet and a type of plaster. LeMoyne believed that this ritual would help protect observers of the cremation from seeing the breakdown of the body in graphic detail. Once it was wrapped, the body would be covered in herbs, spices, pine branches and flowers in an attempt to mask the scent during burning. A reporter sent from the New York Herald, upon observing the preparation of one particular corpse in 1876, wrote that the man to be cremated was covered in “frankincense, myrrh, acacia cinnamon and other fragrant spices.”

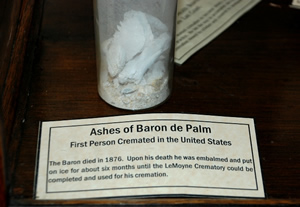

The ongoing construction of the crematory was beginning to draw attention, both positive and negative, in Washington and abroad. In Scott Beveridge’s article, Stephen Prothero, a chairman of religious studies at Boston University is quoted saying, “It wasn’t like it was in New York City, some cosmopolitan city…. The reaction was something you would expect in Middle America; it was un-Christian, shocking.” In response to the unrest, LeMoyne would spend some time hosting public meetings and addresses to the curious locals as well as reporters from around the country. A minstrel show in Philadelphia called, “The Cremationists,” helped to cast a negative light on the crematory calling cremation, “a sudden, ruthless and cruel obliteration of the dead,” according to McCulloch. A small group of local children even built a tiny oven for the cremation of worms. However, not everyone that heard of the controversy was opposed to the idea. In fact, one man who made cremation his final request before death was placed on ice for six months after he passed to wait until the crematory was completed.

In late 1876 at seventy-eight years of age, Dr. LeMoyne had his first volunteer for cremation, the late Baron de Palm. The Baron was a recent immigrant to New York from Austria who despite being a nobleman, at the end of his life, found himself bankrupt and quite ill. Luckily for him, in an effort to encourage those considering it, Dr. LeMoyne vowed to cremate the willing free of charge. Plans were made by LeMoyne and a close friend of the Baron’s, Henry Steel Olcott, and by early December 1876, the Baron’s body was en route to Washington, PA by train.

Olcott and the Baron made it to Pittsburgh on December 5, 1876 and arrived in Washington soon after. According to a New York Herald correspondent along for the ride with the Baron, at two in the morning on December 6, the furnace was lit by James Wolf; it would take several hours for the furnace to reach the necessary temperature of 2,300 degrees Fahrenheit. Although the number of people that could squeeze inside the small crematory was small and limited mostly to physicians, from the onset a great crowd gathered around the building to see what they could of this historical event.

As Clay Kilgore stated, this was the one day in its existence when Washington, PA was the center of the nation’s attention. “[The De Palm cremation] might be considered one of the first media events…. [N]ewspapers from coast to coast contained coverage of it on their front pages,” says Rosen, “Around the building was a noisy, pushing crowd of the young women and men of the place, some of them had been waiting hopelessly pressing for a place for hours.” The New York Herald correspondent reported that when the body was about to be placed in the furnace at approximately 8:20 am on December 6, 1876, “there was a dead rush to the furnace room from the dirty boys and rough country folks outside, who flattened their noses against the window panes to be able to enjoy this delectable spectacle.” By 11:15 am, the cremation was complete. Rosen writes, “The last vestige of the form of a body had disappeared in the general mass. The pelvis, which had hitherto kept its shape, had fallen in, and nothing now remained but a mass of incandescent ashes.…” In all, the cremation had cost $7.04.

The cremation of the Baron did little to change most Americans’ opinions of cremation and their reaction was not encouraging. According to Kilgore, many thought LeMoyne an irreligious practicer of a barbaric, pagan ritual against the teachings of the Bible. The backlash from the religious community due to LeMoyne’s unusual interests was so severe that he left his church. Beveridge’s article on the doctor agrees, “Washington folks had looked upon LeMoyne as a filthy, unkempt old fool who had been excommunicated from First Presbyterian Church for his unconventional beliefs.” Particularly discouraging to the aging doctor were false reports that he made his children sign agreements to be cremated or risk losing their inheritance. As Rosen observes, even a representative from the Brooklyn Board of Health in attendance remained skeptical. It appears that what LeMoyne had failed to realize was that the majority of America was still uneducated and blinded by outdated beliefs and tradition. It would take more than convincing scientific evidence to persuade the public; it would take time.

If there was one positive outcome of Dr. LeMoyne’s cremations, it was that several cremation societies began emerging in the late 1800s to convince the still resistant public. According to Christine Quigley in her book, by the beginning of the twentieth century there were twenty four crematories in the United States and at least thirteen thousand had been cremated. A national group, the Cremation Association of America was established in 1913 and focused its energy on designing and building more crematories. By 1919, the number of crematories in the states would be up to seventy and by the 1950s, the cremation rate was up to four percent.

Unwilling to die without a final attempt at giving cremation a good name, LeMoyne dictated a collection of arguments entitled, “Cremation: An Argument to Prove that Cremation is Preferable to Inhumation of Dead Bodies,” while “under the embarrassment of infirmities of old age, and under the depressing influences of a fatal disease.” In the essay, the doctor suggested several reasons why cremation is superior to burial and related each back to Christian values. He even managed to find passages in the Bible that seem to at least allow, if not support, burial.

First of all, he believed that cremation merely safely speeds up what nature would like to see happen-the return of the body to the earth that created it. Of the animals and microscopic organisms that naturally break down a corpse, he wrote “God in his wisdom and mercy saw the vital necessity of providing a speedy and efficient means for removing decomposing matter, that it might not continue to poison the air…. Inhumation is at direct variance with the lesson taught by this great natural law.” Next, of course, is the sanitary argument, “The inhumation of human bodies, dead from these infectious diseases, results in constantly loading the atmosphere, and polluting the waters, with not only the germs that arise from simple putrefaction, but also with the specific germs of the diseases from which death resulted.” He referenced the first chapter of Genesis in the Bible, “When God created man… he organized the body out of a portion of common earthy matter, and then breathed into that organized body the breath of life, and it became a living soul. This was entirely a different being… from that being which existed previous to that divine act.” LeMoyne argues against the preservation of the body as he feels it is, “of no more consequence than a like quantity of any other earth.” The doctor also spoke of the economical argument, “While great masses of the earth’s population are living in heathenish darkness, how dare Christian men devote so much of their income to the gratification of their own pride and vanity in aiding and abetting the evils of this sinful custom?” In his day burials cost at least $100 and a cremation would not exceed $20.

His most courageous argument is that of the religious merit of cremation. He cited several times in the Bible when God himself either directly or indirectly proposed cremation. First he pointed out that God often interacted with man through burnt offerings of animals and that God commanded Abraham to offer up his son, Isaac, as a burnt offering. Also, in the first book of Samuel in the Old Testament, there is evidence of the cremation of a man named Saul and his sons. LeMoyne says, “The Savior… disparaged the importance of burial [with the words]: ‘Let the dead bury their dead.’”

Finally, he outlined the social and political benefits of adopting cremation in place of burial which he alleged supported the great disparity between the rich and the poor. He believed that inhumation separated society into castes and increased the hostility that was already present between the upper and lower classes. It created a permanent rift because, while the wealthy could afford enormous, ornate monuments, the underprivileged were doomed to free burial spaces in unmarked graves. A counterargument that many anti-cremationists proposed was that, “the seeming violence with which the fire seizes upon the body gives such a shock to their feelings that they cannot look upon or tolerate the process when the body of a dear friend or relative is submitted to the crematory.” LeMoyne reasoned that compared to the “actual offensive, disgusting condition,” of the grave of that friend or relative, cremation should appear the lesser of the two evils. “Cremation treats the body of a prince as it does that of the peasant; the body of the king as that of the commoner; the patrician as the plebian; the President of the United States as the obscurest citizen.”

Two more cremations would closely follow that of the Baron de Palm, Jane Pitman, an art teacher from Cincinnati, and LeMoyne himself. On October 14, 1879, Dr. LeMoyne finally lost his battle with diabetes and old age. His family hoped that his funeral would not draw any of the negative attention that the Baron’s did, but this was not the case. According to McCulloch, many rumors circulated throughout the town regarding what would be done with the doctor’s body. His after-death requests were disappointingly unexceptional however; he desired an autopsy be performed and then “simple, suitable religious services at his home, followed by a strictly private cremation at the crematory.” Following the ceremony, his ashes were buried in an urn outside the crematory marked by a monument: F. Julius LeMoyne, M.D.; Born Sept. 4, 1798; Died Oct. 14, 1879; A Fearless Advocate of the Right.

Today the little crematory still sits at the top of Gallows Hill on South Main Street in Washington, unnoticed by all but those who know to look for it. Although operation ceased in 1901 after forty-one successful cremations, the building remains in remarkable condition due to the continuous care from the Washington County Historical Society. The artifacts inside the building look just as they did over one hundred years ago; with little effort, it seems the furnace could spring back to life. Cremation may still carry a bit of a stigma and be erroneously characterized as a choice of the unreligious; however, with 778,025 cremations for 2,432,000 deaths in 2005, what started in Washington, PA over a century ago continues without threat.

Sources:

- “Americans’ top 10 fears.” Boston.com. The Boston Globe. Web. 30 Nov. 2009. <http://www.boston.com/lifestyle/articles/2009/01/06/americans_top_10_fea....

- “Ashes to Ashes.” New York Herald [New York, New York] 07 Dec. 1876, News/Opinion sec.: 10.

- Beveridge, Scott. “Doctor’s fear prompts crematory.” Observer-Reporter [Washington, PA] 28 Oct. 2007, sec. A: A1-A2.

- “A Cremation Pilgrimage.” New York Herald [New York, New York] 06 Dec. 1876, News/Opinion sec.: 7.

- Culbertson, Fredd. “Phobias From A to Z.” Time.com. Time Magazine. Web. 30 Nov. 2009. <http://www.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,103754,00.html>.

- Davies, Douglas J., and Lewis H. Mates, eds. “LeMoyne, Francis Julius.” Encyclopedia of Cremation. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Limited, 2005. 299-300.

- Davies, Douglas J., and Lewis H. Mates, eds. “Premature Burial.” Encylopedia of Cremation. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Limited, 2005. 348-49. Print.

- Davies, Douglas J., and Lewis H. Mates, eds. “USA.” Encyclopedia of Cremation. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Limited, 2005. 401-09.

- Kilgore, Clay. “LeMoyne Crematory.” Personal interview. 25 Nov. 2009.

- “The LeMoyne Crematory: The First Crematory Built in the United States.” The Washington County Historical Society. 25 Nov. 2009. <http://www.wchspa.org/html/crematory.htm>.

- LeMoyne, Francis J. Cremation: An Argument to Prove that Cremation is Preferable to Inhumation of Dead Bodies. Pittsburgh, PA: E.W. Lightner, 1878.

- McCulloch, Margaret C. Fearless Advocate of the Right. Boston: The Christopher House, 1941.

- Quigley, Christine. The Corpse: A History. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, Inc., 1996.

- Rosen, Fred. Cremation in America. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books, 2004.

- “U.S. Cremation Statistics.” NFDA.com. National Funeral Directors Association. Web. 30 Nov. 2009. <http://www.nfda.org/consumer-resources-cremation/78-us-cremation-statist....