Whether it was on television or in person, many fondly remember the first time they experienced a steam engine locomotive. The large black machine and massive engines that move powerfully with rhythmic chugs easily make an impression on those who encounter them. Many locomotives can trace their roots to the Baldwin Locomotive Works, a company which produced them in Philadelphia, and later in Eddystone, Delaware County. Baldwin Locomotive Works was one of the most prominent names in steam engines during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The company had a large reputation to live up to, with many considering the company “The Name to Beat.” With large-scale production and unique designs, Baldwin Locomotive Works was sure to prove that there was truth in that motto, and they indeed were the name to beat.

Baldwin Locomotive Works was founded by in Philadelphia in 1825 by Matthias W. Baldwin, with the aid of machinist David Mason. Matthias Baldwin, however, did not start his career in the locomotive industry. Around the age of 16, Baldwin began an apprenticeship with a local jeweler. After a few years, Baldwin had his own jewelry company, becoming a leader in the area. Shortly thereafter, Baldwin turned his attention to bookbinding and printing. It was during this time he built his first steam engine to help his publishing process. This design would later go on to serve as the basis for his locomotives. Baldwin did not see much success with books and decided he would go into steam engines full time.

With full attention on steam engines, Baldwin Locomotive Works had started. The first few years for the company were slow. In 1831, however, the company caught a break, and success was soon to follow. The Franklin Perle Museum of Philadelphia turned to Baldwin Locomotive Works to produce a steam engine train for museum patrons to ride. They asked that the company look to a British steam engine design for the process. The company successfully filled the museum’s request. A book on company history, printed in 1897, shares, “on the 25th of April, 1831, the miniature locomotive was put in motion on a circular track…Two small cars, containing seats for four passengers, were attached to it, and the novel spectacle attracted crowds of admiring spectators.”

1831-1913

While the company gained notoriety for their success with the museum display, they also exposed themselves to more steam engine designs, mainly designs from Europe. Members of the company, especially Baldwin, began studying these designs and improving upon them. While these previous European designs were successful, they needed to adapt to the rugged and non-ideal rail conditions found in the United States. The locomotives needed more power and durability to handle the varying terrain found in the country.

Working on designs was full of both success and frustration for Baldwin. In 1832, Baldwin made great strides in making his first, large-scale locomotive since his museum design a year earlier. After working on a project for nearly a year, Baldwin unveiled his newest locomotive, nicknamed “Old Ironsides.” With this success, however, came frustration, as Baldwin found the locomotive too large to fit through the doors of his Philadelphia shop. Making several attempts to get the engine out, Baldwin reached a solution: he planned to cut a hole in his shop to Old Ironsides out, and swore to never work with locomotives again saying “this is our last locomotive.”

Although Baldwin vowed to be done with locomotives, he was surprised with the success Old Ironsides had found. After getting the locomotive out of his shop, Baldwin tested Old Ironsides to see if the frustration was actually worth it. In a six-mile run between Philadelphia and Germantown, Old Ironsides hauled a 30 ton load easily, at a surprising rate of 28 miles per hour. Baldwin was surprised, but he was not the only one to notice. The United States Gazette newspaper noted:

A most gratifying experiment was made yesterday afternoon on the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown Railroad. The beautiful locomotive engine and tender, built by Mr. Baldwin, of this city, whose reputation as an ingenious machinist is well known, were for the first time placed on the road. The engine traveled about six miles, working with perfect accuracy and ease in all its part, and with great velocity.

As a result, Baldwin decided to move to a bigger shop on the edge of Philadelphia and dedicate his work to improving Old Ironsides and his other locomotive designs. With this test, Baldwin Locomotive Works went from being a locomotive company to a locomotive pioneer.

Following the success of Old Ironsides, the company continued making powerful locomotives. One notable locomotive was called “Lancaster,” completed in 1834. At the time, Pennsylvania officials asked Baldwin Locomotive Works to build a locomotive for the “State Road,” a run between Philadelphia and Columbia; a borough located southeast of Harrisburg on the Susquehanna River. Company records state that the locomotive hauled nineteen fully-loaded cars over the rough terrain between Philadelphia and Columbia. As a company history book noted: “This was characterized by the officers of the road as an ‘unprecedented performance.’”

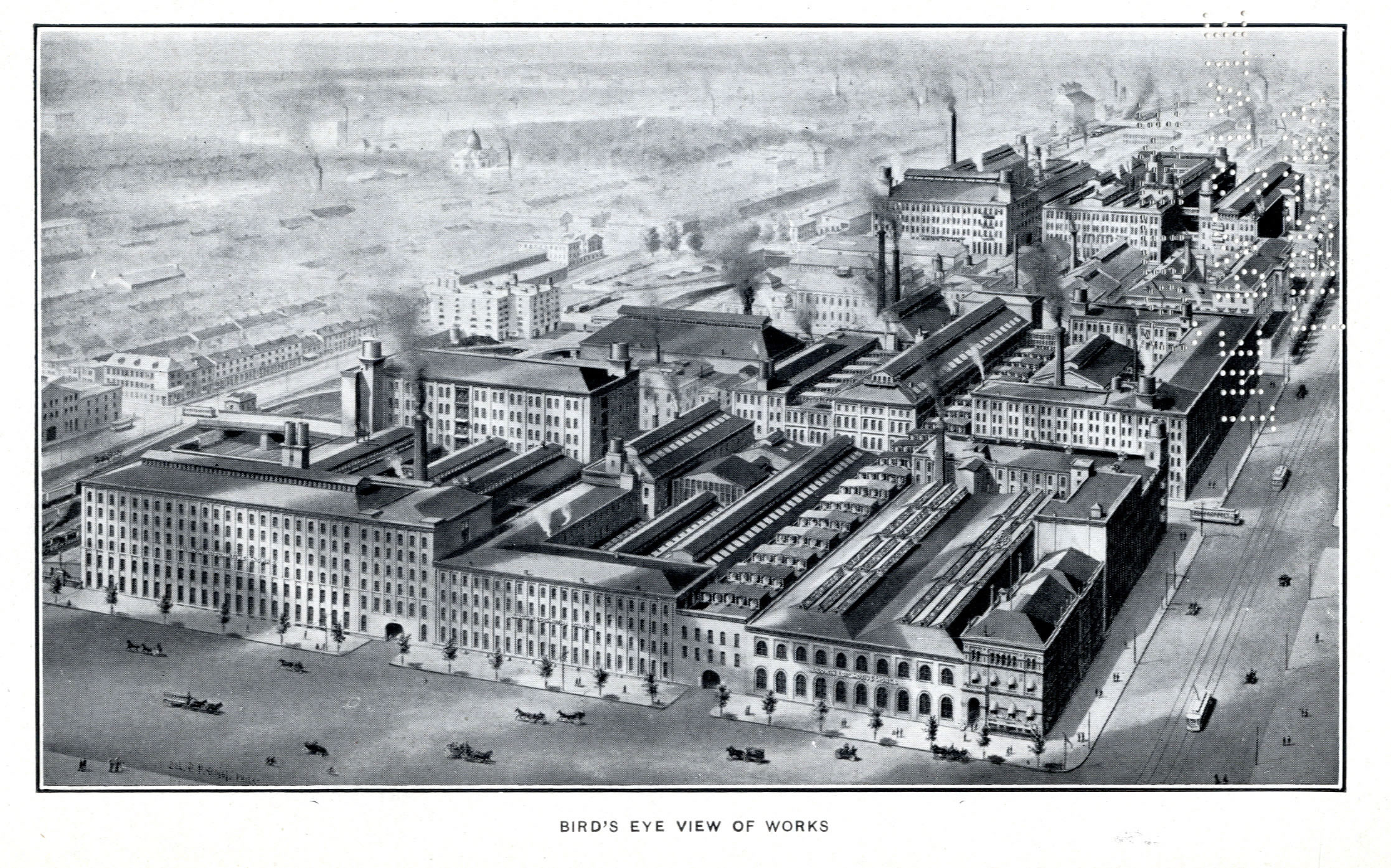

By 1836, Baldwin Locomotive Works had become the top name in the industry. With a shop on Broad Street in Philadelphia, the company was producing 40 locomotives annually, an incredibly high rate for the time. To keep up with demand, the company employed nearly 300 workers. The locomotives all relied on the steam engine which boiled water to generate steam. The steam was then pushed through pistons in the engine to move the train. Baldwin Locomotive Works often experimented with heating the water, attempting to create more steam with less energy. Also, the company worked with creating more power in its engines by pushing steam through the pistons more efficiently.

Over the next several decades, Baldwin Locomotive Works often met with financial problems stemming from an unstable economy. Matthias Baldwin, however, always found a way to rescue his company. Whether it was working with creditors or finding new projects to fund the company, Baldwin knew how to keep the company going when times were difficult. At one point, Baldwin offered everything he owned to creditors, but that only covered a quarter of his debt. It is noted that after this event, “he proposed to them that they should permit him to go on with the business, and in three years he would pay the full amount of the claims.” Baldwin did just that, albeit with some extra time.

Baldwin also made sure his company served customers as well as they could. Historian John K. Brown noted in his book The Baldwin Locomotive Works, “Even when sales were successfully concluded, Baldwin remained bound to his customers by performance guarantees, installment payments, and demand for new designs.” In addition, the company was motivated by a growing nation. Westward expansion was on the rise and railroads were the means of getting there. Going west helped many, but perhaps no more than it helped the Baldwin Locomotive Works.

As a result of this westward expansion, Baldwin Locomotive Works saw great increases in production. To help aid the growth, the company shop—now a booming factory—saw several changes come about. The number of workers increased greatly in the factory, expanding to over 600 employees. Now, instead of Baldwin or other company heads looking over the operations, the factory was divided into separate sections to produce different elements of a locomotive, a precursor to Henry Ford’s famous assembly line work. Each of these sections had their own foremen who would then answer to company heads. Due to this new business model, the company was producing locomotives like never before. In 1857, the company produced 66 locomotives.

Although seeing success like never before, Baldwin Locomotive Works once again had fallen victim to the ever changing economy. By 1860, the company was dealing with striking workers and a year later, began to lose Southern business as a result of the American Civil War. Much as before, Matthias Baldwin worked around any barriers which stood in his way. Although losing Southern business, the company was able to build on the economic benefits of a nation at war. Northern forces turned to Baldwin Locomotive Works for various resources. The Pennsylvania Railroad saw increased use, ultimately turning to the company to help keep up with demand.

Following the end of the war in 1865, Matthias Baldwin set his company up in strong financial position. The company no longer found itself in debt, but instead the clear leader in the locomotive industry. Following a productive year, Matthias Baldwin died in 1866, with “his name as ‘familiar as household words.’” Baldwin’s business partners were left in control of the company. Although no longer alive, Baldwin left the company in a strong financial position and with several innovations on the brink of completion; a long life was ahead of the Baldwin Locomotive Works.

By the late 1860’s, the innovations Matthias Baldwin began to put in place were finally coming to fruition. Perhaps the most notable was the implementation of lighter and stronger steel boilers. These new boilers were both safe and rugged, while providing more power for the locomotive. Historian Harold Davies notes in the book North American Locomotive Builders and Their Insignia, that by 1880, company production “exceeded that of any competitor, worldwide, by a factor of more than two.” This large gap came from solid construction. As Davies points out, Baldwin Locomotive Works build “locomotives that never wear out.”

As competitors came and went, Baldwin Locomotive Works found continued success, resulting from their innovations and strong reputation. By 1900, the company had reached another key innovation in the locomotive industry. Company designer Samuel Vauclain was a tireless worker for the company when he designed the Vauclain Compound engine. In this method, the steam engine held to pistons, one for high pressure steam and the other for low pressure steam. This design led to lower fuel and water consumption, making the engine much more economically efficient. Historian Brian Solomon points out that this design “proved to be one of the most distinctive and successful varieties of compound locomotives.” Solomon also points out how this design “enjoyed greater versatility and could be applied to faster services.” This design proved widely popular, as it is estimated that 70 percent of all steam engines in the United States were of the Vauclain type.

Due to innovations in both design and materials, Baldwin Locomotive Works was producing more locomotives than ever. In 1906, the company produced over 2,500 locomotives. This was done with the help of 17,000 employees who worked around the clock in shifts, to keep the company producing during the entire day. To help accommodate increasing demand, the company built another factory located 15 miles away in Eddystone, Delaware County.

Although seeing much success during the early part of the decade, by 1908 the company was forced to make cuts. Demands for locomotives decreased drastically, leading to thousands of employees being laid off. Though the rail industry was seeing more business than ever, strict regulations saw financial resources stretched, leaving little room for new products. This left everyone uneasy, including factory workers, who would later strike.

While the company was in turmoil, an opportunity for recovery turned up. In 1914, war broke out once again, this time in Europe. Baldwin Locomotive Works once again seized the opportunity presented by World War I. By 1913, the company produced its 30,000th locomotive. Production continued at a high rate for the company. By 1918, the war was nearing its end and the company was finishing its 40,000th locomotive.

Once again, the success found in the company was met with downturn. The war had ended and demand for locomotives had again decreased. Even worse, the innovation that helped Baldwin Locomotive Works become an industry leader was slowly fading. The company’s main competition, the Ohio-based Lima Locomotive Works, was creating larger and faster steam engines, forcing Baldwin Locomotive Works to catch up.

Over the next few years, Baldwin Locomotive Works continued to fall. By 1929, Wall Street had crashed and the Great Depression was beginning. Facing ominous economic times and a slipping grip on its once dominant position, the company found itself in a dire position. The Franklin Institute’s look into Baldwin Locomotive Works explains, “The company was overextended,” and that “sales of capital goods evaporated.” As a result, Baldwin Locomotive Works declared bankruptcy in 1935. The company saw some glimmers of hope, producing electric locomotives for the Pennsylvania Railroad prior to the 1940’s and the onset of World War II, but never was able to repeat the success it had found in the previous decades.

In the years following the war, Baldwin Locomotive Works stayed in business for some time, producing fewer steam engines and more diesel engines. A declining industry, however, forced Baldwin Locomotive Works to merge with former rival Lima-Hamilton, to create Baldwin-Hamilton Works in 1950. Due to low demand, a changing economy, and labor issues, the last Baldwin locomotive was built in 1954. The last locomotive is estimated as the 70,541st built by the company. Although no longer producing locomotives, the company was bought and sold numerous times, leaving the Eddystone factory to produce construction tools. By 1971, the company was purchased by Greyhound Corporation, who closed the company down for good.

Although Baldwin Locomotive Works is no longer active, the impact of the company is still seen today. The Franklin Institute in Philadelphia still displays Baldwin Locomotives, one such is the 60,000th commemorative locomotive, donated to the museum. Even several of the steam engines found in operation around the country today still proudly display the Baldwin Locomotive Works plate, a testament to their longevity. While the company is gone, the legacy of the company Matthias Baldwin started still lives on, sticking true to that original motto that Baldwin Locomotive Works is still the name to beat.

Sources:

- Baldwin-Lima-Hamilton Corporation. History of the Baldwin Locomotive Works from 1831-1897. Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott Co., 1897.

- ---. History of the Baldwin Locomotive Works from 1831-1902. Philadelphia, PA. The Edgell Company, 1903.

- Brown, John. The Baldwin Locomotive Works, 1831-1915. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995.

- The Case Files: Baldwin Locomotive Works. The Franklin Institute. 2010. <http://www.fi.edu/learn/case-files/baldwin/>

- Davies, Harold. North American steam Locomotive Builders & Their Insignia. Forest, VA: TLC Railroad Books, 2006.

- History of Baldwin Locomotive Works, 1831-1923. Philadelphia: Bingham Press, 1923.

- Marx, Thomas. “Technological Change and the Theory of the Firm: The American Locomotive Industry, 1920-1955.” Business History Review. 50.1 (1976): 1-24.

- Sandberg, William and H. Dixon Wilcox. Opportunity Recognition and Disruptive Technology: The U.U. Locomotive Industry from 1920 to 1940. 2002. 2011 <http://www.babson.edu/entrep/fer/babson2002/II/II_P4/II_P4.htm>.

- Solomon, Brian. Baldwin Locomotives. Ed. Dennis Pernu. Minneapolis, MN: MBI Publishing Co., 2010.

- Westing, Fred. The Locomotives That Baldwin Built. Seattle, WA: Superior, 1966.