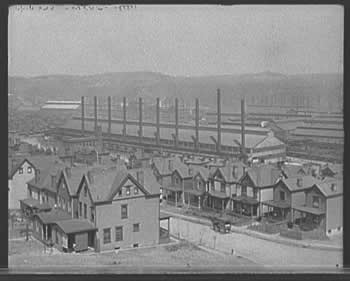

In the summer of 1892, America would witness one of the bloodiest confrontations ever to occur between labor and management. The Carnegie steel empire was at the height of its power, when a disagreement over wages with the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers erupted into a fierce battle at the Homestead works along the Monongahela River, near Pittsburgh. The outcome of this confrontation would not only affect the fate of the individual workers and the mill, but labor and unions throughout the country.

The trouble began early in 1892; the two sides needed to negotiate the contracts of the workers which were set to expire at the end of June. Plant owner Andrew Carnegie and the plant manager Henry Clay Frick gave the union a contract to review, it included a substantial pay cut for some of the positions as well as a proposal to push the expiration of this new contract back to the beginning of January 1894. They cited the falling price of steel for the reduced wages, claiming that workers' pay would increase if prices were up, so they should decrease when prices were down. The union rejected this proposal outright and refused to take pay cuts for any workers. The dispute dragged on and, by May, Frick issued an ultimatum, either agree to the company's pay scale by June 24 or they would be "dealt with individually."

The union leaders refused to back down and prepared for the worst. The union held a large recruitment drive and nearly doubled their numbers from less than 400 men to more than 750. However, the union was not the only side preparing for a showdown. By June 20, Frick had ordered the building of a 12 foot high, three mile long, and two inch thick fence around the mill. The fence was also topped with barbed wire, and equipped with search light platforms and high powered water hoses. On June 23, union leaders attempted to negotiate with management. They agreed to pay cuts, but refused to accept any more than a 15% cut. Frick refused and both groups prepared for a strike.

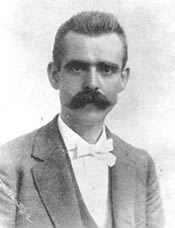

The union began to form a strike advisory committee. The committee consisted of five men, headed by chairman Hugh O'Donnell. However, Frick's deadline of June 24 came and passed with no incident. In fact, the mill was as busy as ever, if not more so over June 25 to 27. This was not to last, however; suddenly on June 28, the armor plate mill and open hearth department shut down without warning, leaving 800 men out of work. Over the next few days, Frick laid off 100 to 200 men at a time, eventually leaving the mill completely empty. By June 30, the mill came to a screeching halt, and all union workers were locked out.

Over the next week, the company made preparations to bring in "scab" workers placing ads in newspapers in Boston, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and even some in Europe to recruit workers willing to cross the picket lines. In order to protect these workers and to capture the mill back from union workers, who took over the mill several days after the lockout began, the company also recruited members of the Pinkerton Detective Agency. This agency consisted of many immigrant workers and was formed by Allan Pinkerton in 1850 in order to aid companies in putting down strikes. Carnegie and Frick had used the group before and this time recruited more than 300 of their men from New York and Chicago.

Unfortunately for Frick, the union workers were aware that he was making plans to bring in scab workers. Workers patrolled the Monongahela River, as it was the easiest way to move large numbers of people into the mill. They also stood guard at the mill itself and established warning systems around Homestead and Pittsburgh.

On July 5, the Pinkerton guards met in Ashtabula, OH and boarded darkened railroad coaches. Upon reaching Dais Island Dam, they were moved into two barges, the Iron Mountain and the Monongahela pulled by two tug boats Little Bill and Tide, and were armed with Winchester rifles. By two thirty on the morning of July 6, the strikers were aware of the Pinkertons' move down the river as the men on guard duty spotted the barges passing under the Smithfield Street Bridge near downtown Pittsburgh. By four o'clock, the Pinkerton guards arrived in Homestead and the town mobilized to meet them.

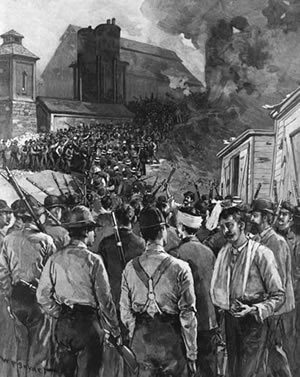

The events that would follow the Pinkertons' arrival would go down in history as the Battle of the Monongahela, and would make the Homestead strike vastly different from most strikes that had come before. As the barges came into sight, they were greeted with a barrage of gun fire and stones hurled through the air. Nearly 10,000 men, women, and children gathered on the river banks armed with anything they could find. Some carried fire arms dating from the civil war, but many others grabbed anything they could find from sticks, stones, and even clubs made from boards pried from fences. Despite the gun fire, the barges pressed on, reaching the entrance to the mill near dawn.

As the barges pulled up to the entrance, the strikers began to charge the fence that Frick built around the mill. In a matter of minutes, it was flattened and thousands of strikers and their supporters poured into the mill to meet the Pinkerton guards. There they were met by a captain of the guards, Charles Nordrum, who told the crowd that they were not looking for trouble as he pulled down the gangplank. The crowd, however, seemed little inclined to believe him as another round of chaos ensued. As no Pinkertons had yet been hurt, Nordrum told his men not to return fire. Over the din, the Pinkerton commander, Fredrick H Heinde, told the strikers that his men were taking control of the mill.

However, the strikers did not take this announcement well. They rained rocks down upon the Pinkerton boats. Three men rushed forward to grab the gangplank. Two took hold of either side, while one lay over the end. As Heinde attempted to step over the man, he was shot in the thigh, which knocked him backward and the strikers opened fire once more. This fresh round of gunfire killed one and wounded four more Pinkerton guards. Now that blood had been spilt, the Pinkertons retaliated. More guards ran on to the deck from below and opened fire killing or wounding more than 30 strikers and sympathizers. The Pinkerton guards then grabbed their dead and wounded from the ship's deck and pulled them below. At the same time, the strikers retreated up the hill behind the mill and began to build barricades from scraps of steel and pig iron. While this initial violent outburst lasted less than three minutes, it left dozens dead and wounded.

As the captain of the guards and several other guards were in dire need of medical care, the tug boat Little Bill left with the wounded guards to find help in Pittsburgh. While necessary, this also left the barges stranded as the Tide had had mechanical problems before arrival forcing it to leave the convoy. The stranded barges prepared for a standoff with the strikers and cut small holes in the sides of the barges from which to fire their rifles. As this was occurring, the strikers were busy gathering dynamite and cannons.

For the next several hours, blasts of intermittent gunfire echoed through the air. The confrontation seemed to have come to a stalemate with both groups struggled with their own dilemmas, the Pinkerton guards needed a way to reach the shore to take control of the mill and the strikers needed a way to get the guards out of the barges in order to kill them. To end this struggle the strike leader Hugh O'Donnell asked to meet with Charles Nordrum. But Nordrum refused saying that O'Donnell needed to meet with those who hired him.

By eight o'clock, some of the guards were getting restless and attempted to swim ashore to begin to take control of the mill, unfortunately for them four where killed instantly. While 12 managed to get to shore and wound a few of the strikers, little came of this and, the strikers began shooting anyone emerging from the barges.

As the city of Pittsburgh awoke, they were becoming aware of the situation in Homestead. The sheriff attempted to get help for the stranded Pinkerton guards by calling the governor of Pennsylvania and asking for aid. However, the governor refused saying that the problem should be dealt with by local authorities. Unfortunately for the guards, many in Pittsburgh sided with the strikers and they began to receive more ammunition, weapons, and reinforcements from other steel workers in the nearby neighborhoods of Braddock and Duquesne.

The strikers knew that in order to win the battle, they needed to get at the Pinkertons in the barges, so they began devising ways to get inside. On their first attempt, the strikers took to the river themselves in several skiffs. They surrounded the barges and began to open fire from the skiffs and threw half pound sticks of dynamite at them. While this did little damage at first, eventually the strikers were able to tear a large hole in one of the barges. The strikers then began to fire into the hole, wounding two more men as they attempted to pull the wounded out of harm's way. Now, the guards began to give up and they waved a white flag out of the hole, but the strikers shot it to shreds.

The strikers' next attempt to tear open the barges involved a large, antique cannon stolen from a local building. The strikers hid the cannon behind a bush and stabilized it by lodging it behind two railroad ties. While this was mildly successful at first, as the first shot tore a hole in the roof of the barge closest to shore, it proved extremely unsuccessful as they continued to fire it. The remaining shots fired where consistently far from the target as it was aimed incorrectly. One shot was so poorly aimed that it killed a fellow striker as he stood nearby.

Meanwhile, the sheriff was once more begging for aid from the governor, only to be turned down again. The guards were still completely stranded in the barges, which were quickly becoming unbearably hot in the July heat. However, every time anyone would appear at a porthole for air, they were shot at by the growing numbers on the shore.

The strikers were beginning to give up on getting the Pinkertons out of the barges. Their next attempt at a decisive victory was to light the barges on fire. First, they dumped hundreds of gallons of oil into the river and tried to set it on fire. However, as the wind was strong and they used a type of oil that burned feebly in the best of conditions, the fire was not strong and blew out almost immediately. Unwilling to give up this idea, the strikers next stuffed oily rags into a raft, lit it on fire, and set it a drift toward the barges. Once again, the attempt failed as the raft missed the ship and drifted by harmlessly.

On board some of the guards were near panic, while others grew apathetic, and others still more determined. Some of the guards were ready to jump ship and swim for safety when a captain threatened them saying they would be shot if they abandoned ship. However, most guards had simply laid their guns aside and were waiting for aid to arrive. Though some where still determined to fight back and shot out of the small holes cut in the ship, killing two more strikers. Meanwhile, in Pittsburgh the sheriff was being turned down once more by the governor for aid for the trapped men.

In another attempt to set the barge on fire, the strikers were now loading oil barrels into an old railroad car on an incline track at the top of a hill facing the river. They set the car on fire and released it, while it barreled down the track at an alarming rate before it flew through the air; it fell well short of the target. The strikers attempted one last time to set the barges on fire. They clouded natural gas around the barges and began to shoot extra fireworks from the recent Fourth of July celebrations into it, while it did cause a small explosion; no damage was done to the barges.

By this time the tug boat Little Bill was on its way back to the barges. As water was running low on board the ships, the aid was much needed. However, as the tug came into view, the strikers opened fire, wounding two of the tug boat's crew. As they and the four others on board dropped to the floor to avoid further injury, the boat was unable to come to the aid of the barges. Now, once again the Pinkertons waved a white flag from one of the barges, only to be shot at once more.

The strikers were now shooting the remaining fireworks at the barges. However, seeing that the situation was far out of hand, O'Donnell called a meeting of the main strikers in the mill. While O'Donnell and the other members of the strike committee were calling for a peaceful end to the conflict, others were unwilling to end the battle. The battle continued for several more hours, but by five o'clock those who wanted peace had regained control. A deal was struck with the Pinkertons. They would surrender in return for guaranteed safety. The terms were accepted by both sides, ending the 13 hour standoff that left at least nine workers and three Pinkerton guards dead as well as wounding dozens on both sides.

However, as the guards were taken onshore, they were beaten by the men, women, and children who were standing nearby. The strikers then boarded and raided the barges before setting them on fire. This treatment of the surrendering guards would become the most discussed and condemned event of the strike.

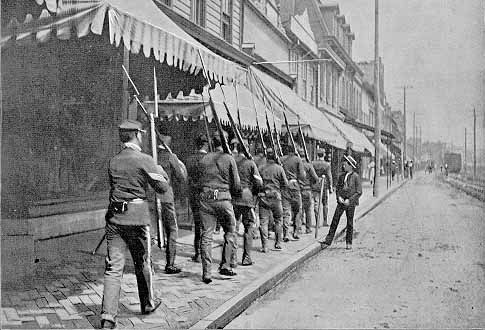

While the violence of July 6, 1892 was ended, the strike continued on. Finally, on July 10 the troops that the sheriff had cried for so desperately during the battle arrived. The more than 8,000 men imposed martial law on the town of Homestead and took back control of the mill. In the months that followed, the company brought in scabs to reopen the mills.

Throughout the summer, the union continued to hold weekly meetings at the local ice skating rink to decide the next course of action. They had much to discuss when legal charges were filed against all of the strike leaders. The charges against them ranged from conspiracy and aggravated rioting to murder for the death of the Pinkerton guards. While the union supported those who were facing legal charges, the legal system soon began to drain the union of resources. By November, the union and union workers were running out of money and supplies. Many of the workers were beginning to attempt to get their jobs back. However, many found that their jobs had been filled by scab workers or that they had been blacklisted for their involvement in the strike. In the end, only around 800 men were able to get their job in the mill back.

This strike had many consequences in several sectors of life. From the first major incident on July 6, the media had taken hold of the story, causing major a sensation throughout the country sparking debates that would rage for months. Along with these debates over the relationship between labor and managers, the public opinion of Carnegie came under fire. While he had left for Scotland in May and had not returned before the battle, it was obvious that he was in close contact with Frick throughout the whole strike. The pair's refusal to call off the guards or to make a deal with the union and to bring a peaceful end to the strike tarnished Carnegie's reputation forever.

Aside from public opinion, the strike proved to be extremely detrimental to the cause of labor unions in steel mills. After the strike the Homestead works would forever be unorganized along with all of the Carnegie companies' steel mills.

Sources:

- Dubofsky, Melvyn, and Foster R. Dulles. Labor in America: A History. 7th ed. Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 2004. 153-170.

- Foner, Philip S. History of the Labor Movement in the U.S. Vol. 2. New York: International, 1955. 206-218.

- Krause, Paul. The Battle for Homestead 1880-1892: Politics, Culture, and Steel. Pittsburgh: U of Pittsburgh P, 1992.

- “Strike At Homestead Mill.” The American Experience. 1999. Public Broadcasting Service. 8 Apr. 2008 <http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/carnegie/sfeature/mh_horror.html>.

- Wolff, Leon. Lockout: The Story of the Homestead Strike of 1892: A Study of Violence, Unionism and the Carnegie Steel Empire. New York: Harper & Row, 1965.