In 18th century Philadelphia, when grassy hills gently rolled from the Delaware River on the east across to the Schuylkill on the west, an infamous building once stood in the most rural township of Philadelphia County, Byberry. Philadelphia’s State Hospital for Mental Diseases was founded seventeen miles outside the city of “Brotherly Love,” a city that retained many small town characteristics, such as an exceptionally open landscape and a calm pace of life, reflecting its Quaker heritage. Additionally, this hospital stood only a few hundred yards from the humble colonial house where the father of American psychiatry, Dr. Benjamin Rush, was born.

In 1751, when Rush was only six years old, Benjamin Franklin and a group of Quakers constructed America’s first hospital for the mentally ill. At this time, Franklin and his fellow brethren voted that the Pennsylvania government should grant public funds for hospitals where, “persons who languish in pain and misery… under disorders of the body and mind may be comfortably subsisted.” This philosophy stood strong, and counties all over Pennsylvania began caring for the mentally ill in almshouses like the one Franklin built. In a report from the sub-committee of the Citizen’s Committee on Municipal charities, 16,992 insane people were being cared for in these facilities. These numbers translate to about one person to every 457 in the population.

From 1830 to 1910, a 45 percent increase of the insane in the general population occurred. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, in public institutions this number increased by about 124 percent, or three times as much as in the general population. This increase necessitated the construction of bigger and better institutions for the mentally ill. The project to build an improved mental institution, the Philadelphia Hospital for the Insane, began in the 1900s when Dr. Joseph S. Neff, director of the Department of Public Health and Charities, wrote to Mayor Reyborn in his annual report that:

The urgent need for the proper institutional care of the feeble minded has been dwelt upon in each of the preceding annual reports, from philanthropic, sociologic, and economic standpoints…the segregation of mental defectives would prove one of the best investments that could be made by the municipality.

In April 1911, a writer from the Philadelphia Inquirer reported that Dr. Joseph S. Neff and the Councils of Joint Committee on Health and Charities would visit other state institutions, including one in Cleveland, Ohio for the purpose of “obtaining data and knowledge,” which would be applied to the building of Philadelphia’s Hospital for Mental Diseases. After two years of research, Neff’s plan for the institution included two large buildings for the mentally incompetent female patients, two lower class resident buildings, six buildings for the residents in the upper class, six buildings each for the female and male mentally insane and, additionally, an administration building, a power plant, storage warehouses, and a series of cottages for physicians and nurses.

Philadelphia’s State Hospital for Mental Diseases, also known as Byberry Insane Asylum, was built at the end of Roosevelt Boulevard in the Somerton section of Northeast Philadelphia. For nearly 200 years, Northeastern Philadelphia had treated its surrounding mentally ill citizens “to keep them off the streets” because they caused “terror among their neighbors.” Byberry Insane Asylum began as a progressive plan to give ill residents options. It allowed patients the opportunity to be medicinally treated instead of being punished as criminals. Mayor Reyburn affirmed this improvement in his report to the council by testifying that:

particular attention has been devoted towards planning the creation of institutions for the segregation and care of the feeble minded…It is planned to erect a number of buildings, separate structures being devoted to different sexes and aged groups…the unit system of institutional construction not only will afford an opportunity for better treatment, but will enable the city to …provide additional buildings as needed.

Reyburn also vowed that the Philadelphia Institution, through its care and treatment for mentally insane patients, would be “an example for the rest of the country.”

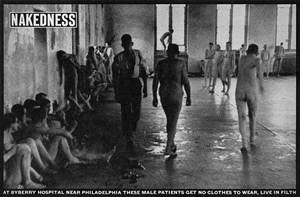

Before the asylum opened its doors, Philadelphia was generally regarded as a pioneer in helping the mentally ill. Therefore, when the Philadelphia Hospital for Mental Diseases opened its doors for its first patient in 1912, its population quickly grew. However, its reputation for humanity did not increase accordingly. Instead, with the influx of patients came tales of abuse, neglect, and deprivation. Insufficient funds led to the asylum quickly falling into disorder. Patients slept in hallways because of overcrowding. Patients’ naked bodies were exposed because clothing was not a necessity. Raw sewage was found on the bathroom floors during one facility inspection.

These deplorable conditions, unearthed during a 1936 grand jury investigation, forced Mayor S. Davis Wilson to sign Byberry over to the state. This transfer of control, however, did little to alleviate the problems in the facility. The state’s first superintendent, Dr. Herbert C. Woolley, told a reporter of the Philadelphia Daily News that his efforts to bring about changes were fruitless. “When I came here,” he said, “Byberry was a medieval pest house. It’s now the equal of an 18th-century insane asylum. It’s a disgrace to any community or government which calls itself civilized.”

Neglect was one of the main problems that infested the inside of Byberry’s stone walls. Through legislative penny-pinching, this institution could not support its staff on payroll, and the shortage of doctors, nurses and security soon became appalling. Byberry housed more than 6,100 patients, about 75 percent over its normal capacity, and only had 180 attendants. According to the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the attendants at Byberry were only about 16 percent of the standard requirement. To make matters worse, there were only 14 on-staff physicians, 90 nurses and one attendant for every 300- 400 patients.

The inhumane treatment of Byberry’s patients was largely hidden from the public eye until 1946. In that year, two separate journalists reported on the conditions at the asylum. Life magazine reporter Albert Maisel focused on the lack of proper staffing at Byberry. In the article “Bedlam 1946,” Maisel proclaimed, “the fact is that beatings are merely the extreme end product which thrusts upon overworked, poorly trained and shamefully underpaid employees the burden of controlling hundreds of patients whom they fear and despise.” Journalist Albert Deutsch of the New York Star also gave a firsthand account of the “hellish scenes” he witnessed during his visit to Philadelphia’s State Mental Hospital in his book, The Shame of the States. From the exterior, Byberry proved aesthetically pleasing, but the inside showed the facility’s degradation. Deutsch explains:

I was reminded of the pictures of the Nazi concentration camps at Belsen…I entered buildings swarming with naked humans herded like cattle and treated with less concern, pervaded by a fetid odor…living under leaking roofs, surrounded by moldy, decaying walls and sprawling on rotting floors for want of seats.

Deutsch’s muckraking led to reforms, but the hospital’s patient population continued to grow at rates that the hospital’s funding could not match.

By the 1960s, under the administration of Dr. Daniel E. Blain, Philadelphia State Hospital consisted of over 50 buildings. The population of the asylum peaked at 6,885 patients and 800 staff members, incurring steep annual costs. In 1963, President John F. Kennedy, motivated by his own sister’s mental illness, recommended the deinstitutionalization of large mental asylums. This nationwide deinstitutionalization would allow for the creation of smaller mental health facilities, which would be able to provide more personal patient care.

Following President Kennedy’s idea of reforming psychiatric facilities in the U.S., Pennsylvania Governor Bob Casey Sr. called for the surveying of Byberry Insane Asylum in 1987. As a result of these thorough investigations, horrid living conditions, including inadequate treatment, mismanagement, and patient abuse such as sexual exploitation and starvation, were publicized. On December 8 of that year, the Philadelphia Daily News reported that five Byberry officials were fired after the hospital was cited for a “history of neglect, poor management, absence of treatment and rampant abuse.” Following these negative reports about health conditions, Byberry was mandated to close. Byberry was soon shut, causing buildings to be boarded up, staff to be relieved of duty, and patients to be discharged. In June 1990, Byberry Insane Asylum released its last two patients, closing its doors forever.

Byberry was scheduled for demolition in 1991, but bulldozing was brought to a standstill when vast amounts of asbestos were found within the building’s walls. Asbestos companies estimated that it would cost $16 million to remove the asbestos, which did not include the demolition fees. Due to the overwhelming price tag, Byberry was left to rot. Left abandoned, the former asylum became a sanctuary for loiterers. With insufficient security patrolling the land, and a multitude of horror stories surrounding its history, Byberry became a popular destination for vandals and graffiti artists.

Byberry’s sordid history finally came to a close in 2006. After sixteen years of abandonment, Byberry was finally demolished in June 2006 when John Westrum, chief executive of Westrum Development Company, began tearing down the buildings that had once been Philadelphia’s State Hospital for Mental Diseases. The 75 acres of now-vacant land will become Westrum’s senior citizen housing community, comprised of 398 luxury units starting at $300,000 each. Ironically, the space that once housed the under-funded facility capable of creating so much suffering will now have streets named Sunflower Drive and Honeysuckle Lane, to inspire a sense of coziness in its senior residents.

Byberry was built with the best of intentions, but never lived up to the dreams of providing the kind of care that Benjamin Franklin advocated centuries ago. Franklin perhaps summed up the situation best himself when he said, “All human situations have their inconveniences. We feel those of the present but neither see nor feel those of the future; and hence we often make troublesome changes without amendment, and frequently for the worse.”

Sources:

- “Conference Will Show New Ways to Treat Insane to Depict Inadequate Facilities throughout Country.” The Philadelphia Inquirer 23 Feb. 1913, sec. 54: 15.

- “Councils to visit Insane Asylums to obtain data.” The Philadelphia Inquirer 23 Apr. 1911: 1.

- Dieckmann, Janna. Caring for the Chronically Ill. New York: Garland, 1999.

- Deutsch, Albert. The Shame of the States. New York: Arno Press, 1973.

- Franklin, Benjamin. Ben Franklin’s Wit & Wisdom. White Plains, NY: Peter Pauper Press, 1956.

- Maisel, Albert Q. “Bedlam 1946.” Life Magazine 6 May 1946: 102-118.

- “Medicine: Herded Like Cattle.” Time.com 20 Dec. 1948: 69.

- Morrison, John F. “A Fruitless 60-Year Battle for Reform.” Philadelphia Daily News 8 Dec. 1987: 11.

- Norfleet, Nicole. “Byberry, from nightmare to dream.” McClatchy - Tribune Business News 31 May 2008. Wirefeed.

- “Philadelphia State Hospital (Byberry).” Opacity. 6 May 2009. 5 Oct 2009. <http://www.opacity.us/>.

- Silcox, Harry. “Mental Giants.” Philly.com. 10 Sept 2009. 17 Sept 2009. <http://www.philly.com/community/pa/philadelphia/netimes/Column_Living_in....

- Silcox, Harry. “Byberry’s sad saga.” Philly.com. 23 Sept. 2009. 16 Nov. 2009. <http://www.philly.com/community/pa/philadelphia/netimes/60709647.html>.