When asked about the War of 1812, most people are apt to respond with blank faces and the nagging feeling that they should remember more about it. Those who are able to come up with a detail related to the War will mention Francis Scott Key writing “The Star Spangled Banner,” Dolly Madison rescuing a portrait of George Washington from the burning White House, or Johnny Horton’s 1959 hit “The Battle of New Orleans.” Coming in a distant fourth is likely one of the artifacts from the War that is most relevant to Pennsylvania: Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry’s battle flag, emblazoned with the phrase: “Don’t Give Up the Ship.” Initially flown from atop the U.S.S. Lawrence in the Battle of Lake Erie, the flag was transferred to her sister ship, the eventual Flagship of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania: The Brig Niagara.

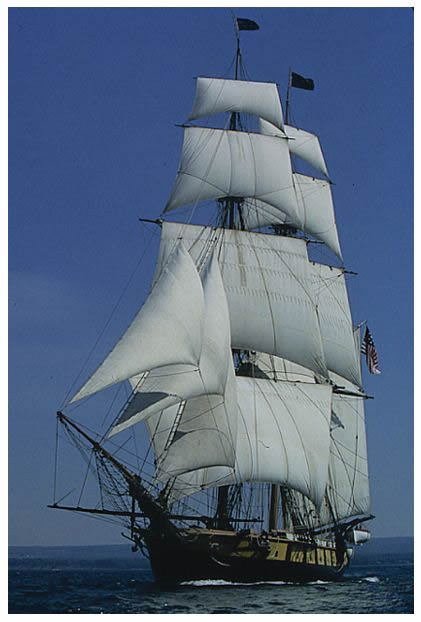

The Brig Niagara was a United States battleship built in conjunction with five other ships, including its sister ship the Lawrence, for combat against the British Navy on the Great Lakes during the War of 1812. The Niagara was an impressive ship for its time. According to Denys Knoll in his book Perry’s Victory on Lake Erie, the Niagara was a two-masted ship that measured 118 feet in length. It was made from very thick oak—the planks on the deck alone were three inches thick. The keel of the ship was made out of black oak timber that measured 14 by 18 inches running along the length of the ship. According to Theodore Roosevelt in Naval War of 1812, The Niagara weighed 480 tons. In The Building of Perry’s Fleet, Max Rosenberg states that while Roosevelt estimated the weight of the Niagara at 480 tons, master shipbuilder Noah Brown claimed it was around 493 tons and Commodore Perry estimated its weight at only 260 tons. According to Roosevelt, the largest British ship on the Great Lakes, Detroit, weighed just ten tons more than the Niagara and according to Perry, the Detroit weighed just forty more tons than the Niagara. These measurements put the size of the Niagara into proper perspective as the second largest ship sailing the Great Lakes during its time period.

Not only was the ship large for its time, but it was also very intimidating. It was equipped with twenty cannons on the one hundred foot long gun deck. Eighteen of them shot the large 32-pound cannon balls and were used for short range bursts and to inflict a lot of damage on enemy ships. The remaining two cannons were used for long range attacks and fired smaller 12-pound cannon balls. The ship with the largest number of canons on the British side was the 19-gun Detroit—one fewer than the Niagara. Knoll claimed that the Detroit was actually built in response to the Lawrence and the Niagara. The British needed a large vessel that could match the size and fire-power of the two American ships. As sister ships, the Lawrence and the Niagara were built with exactly the same dimensions but would have very different fates in the war.

The pivotal naval battle of the War of 1812 was the Battle of Lake Erie. The forces that led the British and the Americans into this battle also drove the construction of one of the biggest and most intimidating ships of its time—the Brig Niagara. The building of this ship, along with the others in the fleet that defended Lake Erie against the British, took place off the shores of Lake Erie.

Captain Daniel Dobbins first brought the need for a fleet on Lake Erie to the attention of the Federal Government. On a trip to deliver supplies in 1812, Dobbins witnessed the capture of Fort Detroit by the British. He was also captured but was able to negotiate his freedom and passage back to his home in Erie. Upon arrival, he brought news of the fall of Detroit, worrying the inhabitants of Erie. Erie could very easily be captured also if adequate measures were not taken. To ensure these measures were taken, Dobbins traveled to Washington, DC. Once informed of the situation, President James Madison discussed possible solutions with his cabinet. Dobbins made a strong pitch for Erie to be the place of construction of the fleet.

Dobbins argued that the natural bay created by the Presque Isle peninsula would serve as a perfect harbor to build the necessary ships. There was a sandbar at the entrance to the bay with only a small path cut through the sandbar to allow entrance. Only sailors who were extremely familiar with the area could successfully navigate through the sandbar. This would make a perfect safe haven for the construction site because the British would not be able to attack the ships in dry dock. A second advantage to Erie was the supply of large oak trees by the water’s edge. Timber would not have to be transported a long way to build the ships. Due to these natural reasons, Erie was a very good candidate for the site to construct the fleet. In September 1812, Dobbins received authorization and funding to begin construction of four battleships. Initially, the Niagara was not included in this package of ships. This changed when Captain Chauncey unexpectedly visited Erie to examine the progress of the construction. He thought that the ships were too small and ordered that the ships that would become the Lawrence and the Niagara be built. At that time, a master shipbuilder from New York, Noah Brown also joined in the construction of the fleet.

The decision to build the fleet of ships, including the Niagara, had a great impact on the city of Erie at the time. In Perry’s Victory on Lake Erie, Knoll describes pre-1812 Erie as a settlement of about 400-500 people that was started just seventeen years prior to the building of the ships. Most of the settlers were merchants who made a living from the salt trade through the Great Lakes. In Daniel Dobbins: Frontier Mariner, Robert Ilisevich claimed that although there was a sizeable population in Erie, ship-carpenters and artisans were hard to find. This changed dramatically by 1813. Erie was starting to become a militarily-based town. There were hundreds of militia men from lower Pennsylvania now roaming the city. Shipbuilding became the primary focus of the town. Any person who wanted a job could find one working under Dobbins on the construction of the fleet. The shipbuilding project expanded the city from the young settlement that it had been and put it on its way to becoming the city it is now—the fourth largest in Pennsylvania.

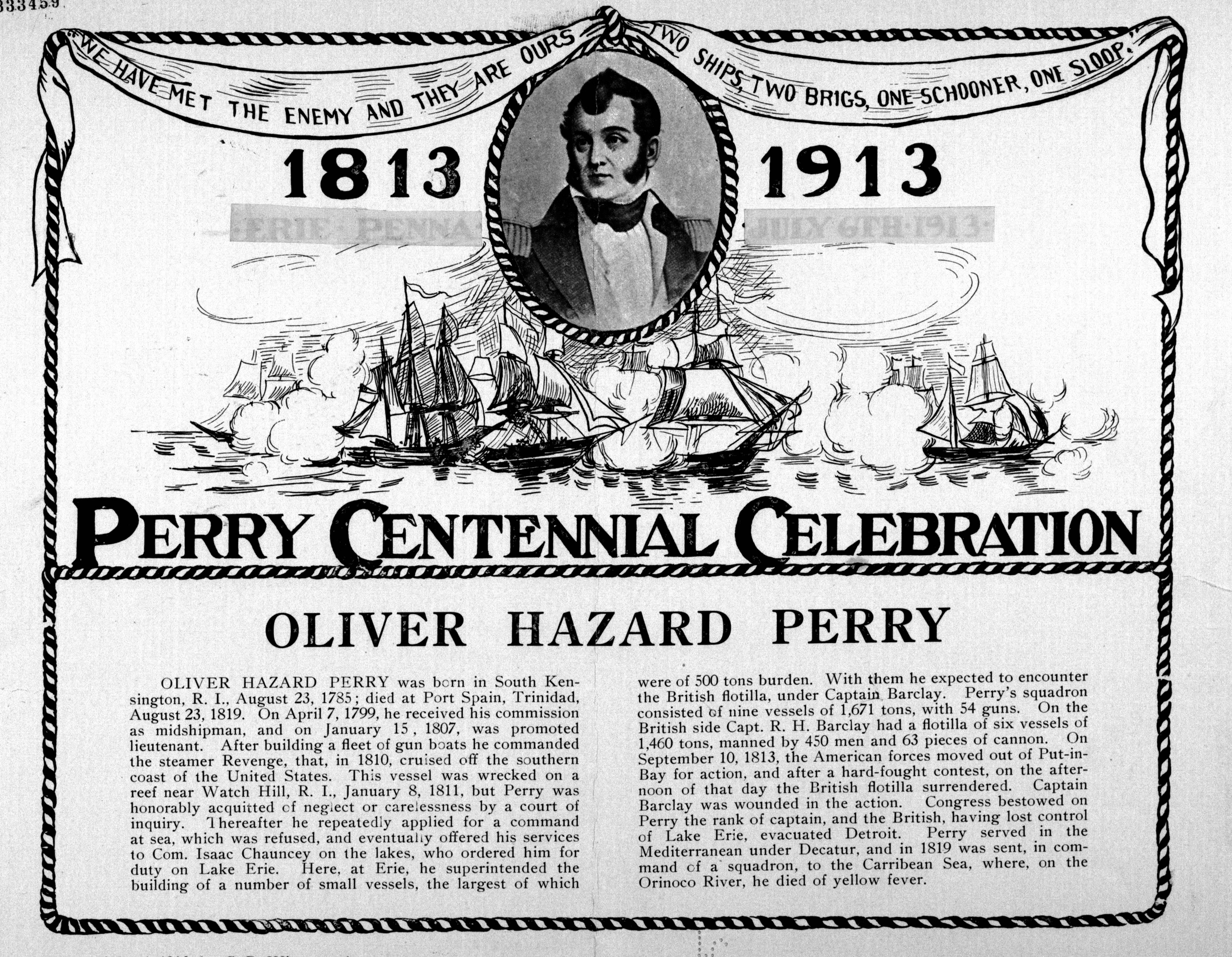

The Niagara was extremely important in the War of 1812. It was initially built to fight the British on Lake Erie and is most famous for its performance in the pivotal Battle of Lake Erie. Oliver Hazard Perry was chosen to command the fleet against the British. Perry started out on the Lawrence. In the beginning, the British had the upper hand against the American fleet. About halfway through the battle, Perry made a bold move and changed from the Lawrence, which had taken heavy damage, to the relatively untouched Niagara. He sailed the Niagara into the fight, cutting the British formation in half with the Chippeway on one side and the Charlotte and the Detroit on the other side. Sailing between these ships, it opened fire from both sides of its deck, smashing the enemy ships with cannon balls from its twenty cannons. Shortly after, the British surrendered to Perry and the Americans in what would be the most pivotal battle on the northern front of the War of 1812.

Although it did not have as much success in later missions as it did at the Battle of Lake Erie, the Niagara did continue in the service of her country. The Niagara took part in the Lake Huron Campaign in 1814 under Commodore Sinclair. The objective of this mission was to remove or capture British forts on the lake. In Fighting Sail on Lake Huron and Georgian Bay, Barry Gough quotes the Navy Department’s instructions to Sinclair as to “…rout the enemy, retake Michilimackinac, take St. Joseph, and thus secure command of the Upper Lakes.” Sinclair wanted to destroy the shipbuilding yard at Matchedash Bay, in the northeast corner of Lake Huron in Canada, but because of unfamiliarity with the area, he was not able to find it; he abandoned the plan and headed to St. Joseph.

St. Joseph is an island located in the northwest corner of Lake Huron. There was a British fort on the island that Sinclair wanted to capture. To his dismay, when the fleet reached the fort, it was already abandoned. One up-side of this mission, however, was the capture of the British trading ship Mink by the Niagara. The next ship captured by the Niagara was the Nancy—another ship taking provisions to British soldiers at Michilimackinac, located on the north tip of the lower Michigan Peninsula. The Niagara also captured the Perseverance and the Batteau before returning to Erie. It then served as a receiving ship in Erie until 1820. This meant that since the Niagara was still in good enough condition to stay above water but is was obsolete to fight or sail a lot, it just served as a place to stay for new sailors before they were put on another ship for service.

When the war ended in December of 1814, the need for large battleships on the Great Lakes disappeared. According to the National Park Service, the Rush-Bagot Agreement—calling for the disarmament of the Great Lakes—made the Niagara, along with any other gunships, useless on the Great Lakes. The Niagara then became a station ship at Presque Isle; it stayed within close proximity of the peninsula and did not freely sail the Great Lakes. When the Erie Naval Station closed in 1820, the brig was scuttled in Misery Bay—the natural bay created by Presque Isle. Since the water is cold there, it preserved the Niagara. The site was chosen intentionally so the ship could be raised if conflict with Canada ever started again.

According to the Historical Naval Ships Association, the Niagara was raised in 1913 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Battle of Lake Erie. It was towed to different ports on the lake and put on show temporarily before returning to Erie where it became a museum ship. The National Parks Service said that the design for the reconstructed Niagara was made by noted naval historian Howard I. Chapelle because the original plans could be found neither at the Navy Department nor in the National Archives. In 1931, the ship became the property of Pennsylvania and a second restoration was commissioned. This was much delayed by the Great Depression and the Second World War and was not finished until 1963. The ship still had some of its original planks, but it was not able to be sailed safely.

Then in 1980, ship designer Melbourne Smith drew up plans for another restoration and oversaw progress. By 1990, the restoration was finished and the ship was able to safely sail. According to the Erie Times News, the mast of the ship was replaced in 2008. The old yellow pine mast was replaced with a new Douglas fir one, the most recent change made to the Brig Niagara. The final specifications for the restored ship are a little different from the original. The Erie Maritime Museum gives the length of the new ship to be 123 feet in length as compared to the 118 feet that it was before. It is still armed with four short range cannons, firing 32-pound cannon balls.

The brig Niagara is one of three US ships remaining from the War of 1812. It is also on the National Register of Historic Places and is the Pennsylvania state flagship. It currently sails around the Great Lakes with a crew of twenty full time sailors and twenty volunteers. When not sailing, it is docked in Erie and remains a major landmark for the city. In May 1998, the Erie Maritime Museum opened and is now the location of the home port of the brig Niagara. The museum’s major exhibit is, of course, the reconstructed brig. It also contains a reconstruction of the middle of the Lawrence. This reconstruction is compared to another reconstruction that had been shot at by the cannons of the brig Niagara. This exhibit shows how much damage the cannons of the ships fighting in the war could do. It illustrates the extent of the damage that the Lawrence was under during the battle. There is also a variety of multimedia that display the story of the Battle of Lake Erie.

The harbor at Erie allows visitors not only to see a living bit of history, but also to take themselves out of the seemingly implacable problems of today and let them see successful solutions of the past. Pennsylvania’s flagship, the Niagara, is not merely a museum ship. It reminds us daily of the need to never “give up the ship.”

The Center wishes to thank The Erie Maritime Museum for its assistance in illustrating this article.

Sources:

- “The Brig Niagara.” nps.gov. n.d. 10 Nov. 2009 <http://www.nps.gov/archive/pevi/HTML/Niagara.html>

- Collins, Gilbert. Guidebook to the Historic Sites of the War of 1812. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1998.

- Gough, Barry. Fighting Sail on Lake Huron and Georgian Bay. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2002.

- Heidler, David S., and Jeanne T. Heidler. The War of 1812. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002.

- Hickey, Donald R. Don’t Give Up the Ship: Myths of the War of 1812. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

- “History.” Erie Maritime Museum. Flagship Niagara League. 2009. 10 Nov. 2009 <http://www.eriemaritimemuseum.org/maritime_museum/History/>.

- Ilisevich, Robert D. Daniel Dobbins: Frontier Mariner. Erie, PA: Erie County Historical Society, 1993.

- Knoll, Denys W. Perry’s Victory on Lake Erie: An Account of the Building of the Fleet in the Wilderness; the Decisive Battle at Put-In-Bay, and its Consequences. Erie, PA: Erie County Historical Society, 1980.

- The Lilly Library. An Exhibit to Commemorate the One Hundred Fiftieth Anniversary of the Beginning of the War of 1812. Indiana, PA: Indiana University, 1962.

- The Naval War of 1812. Ed. Robert Gardiner. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1998.

- “Niagara History.” brigniagara.org. US Brig Niagara and Erie Maritime Museum. 7 Dec. 2007. 10 Nov. 2009 <http://www.brigniagara.org/niagara_history.htm>.

- Roosevelt, Theodore. Naval War of 1812. New York: G.P. Putnam’s and Sons, 1910.

- Rosenberg, Max. The Building of Perry’s Fleet on Lake Erie 1812-1813. Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1987.

- “U.S. Brig Niagara.” Historical Naval Ships Association. 2008. 10 Nov. 2009. <http://www.hnsa.org/ships/niagara.htm>

- War on the Great Lakes: Essays commemorating the 175th Anniversary of the Battle of Lake Erie. Ed. William Jeffrey Welsh and David Curtis Skaggs. Kent, OH: The Kent State Press, 1991.

- Weber, Sarah. “Brig Niagara Trades in Yellow Pine for Douglas Fir.” Erie Times News 20 Mar. 2008. GoErie.com. 10 Nov. 2009. <http://www.goerie.com/apps/pbcs.dll/ article?AID=/20080320 /NEWS02/803200421>.