Strolling along the pinkish gravel towpath where mules used to pull cargo-laden boats decades ago, families, bikers, and joggers enjoy the charming scenery of the Delaware Canal today. The canal has been out of commission since 1940 and was eventually turned over to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to become a National historic park. Interestingly, the Delaware Canal served as one of the first biggest projects undertaken in the early history of the United States and today gives visitors a glimpse back into the past way of life in the 19th century.

The story of the Delaware Canal dates back to the early 1800s when the American economy was booming in the pre-industrial revolution era and westward expansion had begun. Coal started to become an important commodity when blacksmiths harnessed the coal’s use in their forges during the American Revolution. (A forge is a special fireplace, hearth or furnace in which metal is heated before shaping to make weapons for the soldiers.) The first consumer use of coal occurred in 1808 when Judge Jesse Fell of Wilkes-Barre, PA successfully used it in a grate fire. The next attempt to introduce coal to the general market happened after the War of 1812 when three townspeople also of Wilkes-Barre, Charles Miner, Jacob Cist, and a Mr. Robinson, went to various houses in Philadelphia and blacksmiths to demonstrate how the coal should properly be utilized. Cist even created a stove designed specifically for the use of anthracite coal. This sparked the boom in the coal market and anthracite coal started to be in serious demand. However, a shipment of anthracite coal from the coal mining areas of northeastern Pennsylvania to the eastern cities provided a difficult challenge since poor roads and unnavigable rivers made coal transportation both time consuming and inefficient.

A solution to the problem led legislators to push for a canal system, since canal models in Europe and Asia proved to be faster and cheaper modes of transportation. Additionally, the overwhelming success of New York’s Erie Canal also helped to spur the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to begin construction of a 1,200-mile canal system to connect Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Lake Erie. This new route would eventually become a major mode of transportation of manufactured goods and raw materials during the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century.

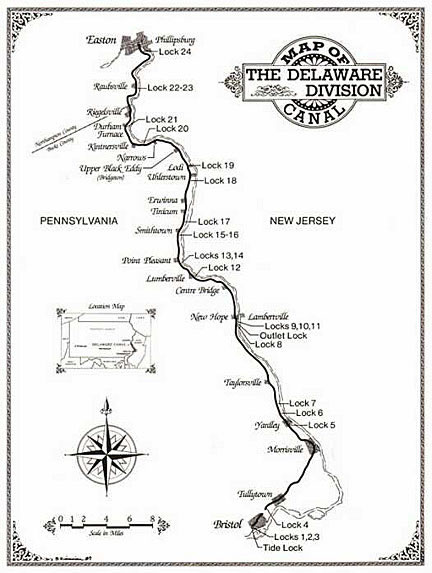

One part of this great canal network is the Delaware Canal. Official construction of the 60-mile long canal started in 1827 and was completed in 1832. It was constructed on the west bank of the Delaware River from Bristol, PA running parallel to the Delaware River up north to Easton, PA to connect to the Lehigh Canal. The Delaware Canal runs through the present-day counties of Bucks and Northampton. The Delaware River itself was not utilized for goods transportation due to strong currents and rapids. Unfortunately, the contractors hired by the Commonwealth to build the Delaware Canal did not construct the canal sturdily enough and it had to be quickly shut down soon after opening for operation because it leaked so badly. The Pennsylvania Canal Commission then asked Josiah White, co-founder of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, to rebuild the Delaware Canal division.

Although White thought the Delaware River itself should be transformed with dams, locks, chutes, and slack water pools to make the river navigable for product transportation, White decided to rebuild the Delaware Canal since it would prove profitable for his own business, the Lehigh Canal. White wanted to widen the Delaware Division’s locks to 11 feet to match the 22 foot locks of the Lehigh Canal, but the commissioners would not let him. Consequently, this imposed a 100-ton cargo limit on any barge wishing to navigate the canals. This greatly hindered the waterways since they had to carry fewer goods along both canals. A dam was constructed across the entrance of the Lehigh River in Easton, PA to supply the water necessary to operate the Delaware Canal, and a waterwheel was built near New Hope, PA to allow for the additional supply of water for the lower sections of the canal. The Delaware Canal reopened for navigation successfully in 1834.

A system of 24 locks and 9 aqueducts were employed to raise the Delaware Canal 165 feet to Easton’s elevation. Locks were vital for the proper transportation of commodities along the canal. A lock is a stretch of water enclosed by gates with one at each end built into a canal or river for the purpose of raising or lowering a vessel from one water level to another. In order for the cargo to be pulled back and forth along the canal by mules, a tow path was constructed parallel to the Delaware Canal. Aqueducts were also important features of the canal system since they provided the stability for the canal structures. An aqueduct is a bridge-like structure supporting a canal passing over a river or low ground. This combination of the tow path, locks, and aqueducts made the Delaware Canal system run efficiently as possible.

The canal’s most productive years date back to just before the start of the Civil War. Over 3,000 mule-drawn barges traveled up and down this route, transporting over one million tons of coal per year. Smaller quantities of products, including lumber, building stone, produce, and lime were also carried. On average, a mule-powered boat could carry 80 tons of cargo over 30 miles or more each day. However, the success of the canal was short lived because eventually the canal’s competition with the railroad industry decreased profits of the Delaware Canal.

In 1858, the Commonwealth made the decision to sell the Delaware Canal to the newly formed Delaware Canal Division Company for $1.78 million. Even though the Delaware Canal was the only part of the state-owned canal system that was consistently profitable, the debts of all of the other canals forced Pennsylvania to sell all of its canals. Then from 1866 to 1931, the Delaware Canal Division Company leased both the Delaware Canal and the Lehigh Canal to Josiah White’s Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, the primary user of the canals during this time. The canals started with just 365 tons of coal being shipped in 1820 and this number climbed to more than 1 million tons being shipped annually in 1859. On the other hand, the Delaware Canal alone reached its peak volume in 1860 when 792,000 tons passed along the canal. Unfortunately, a steady decline in the amount of cargo being transported had begun and by 1915, only 135,000 tons were being carried per year. Trains eventually beat the canal system and the Delaware Canal became obsolete in 1931, when the last anthracite coal shipment was made.

Shortly after, Governor Gifford Pinchot named the Delaware Canal the Roosevelt State Park in honor of his fellow preservationist, Theodore Roosevelt. The name of the park was changed to Delaware Canal State Park due to popular demand in 1989. The Delaware Canal’s significance in American history was realized in 1978, when it was recognized as a National Historic Landmark because it is the most fully intact waterway of all the canals in the United States. Unfortunately, several recent storms have caused major flooding and damage to the tow path and canal. Therefore, sections of the canal are closed to Delaware Canal State park visitors until repairs can be made. Yet, there is still a good stretch of tow path open for those who want to go on a good long walk or jog.

In addition to taking a stroll along the scenic canal, there is one lock of the Delaware Canal system that has been restored and is open to the public who wish to see a live demonstration of a lock in action. It is located seven miles north of New Hope in Lumberville. Moreover, in New Hope at Lock 11 there is the Lock Tender’s House, a small museum that has exhibits on display about the Delaware Canal. A special experience is also offered at Lock 11 where visitors can take an old fashion mule-drawn boat ride down part of the Delaware Canal and recreate a small part of history with family and friends. In addition to the mule-drawn barge rides and canal, there are plenty of shops and restaurants in the canal-neighboring towns of New Hope and Lambertville, NJ that will certainly create a fun weekend for all.

Albright “Zip” Zimmerman, former professor of history and American studies at Rider University, lives near the Delaware Canal and has been a canal enthusiast since 1965. He believes the history of canals is very important for everyone to appreciate because the future is determined by the past and since canals were one of the first modes of transportation, it would be a shame to lose their rich history: “Canals are a part of our heritage. If we don’t give them attention, they’re lost, and they’re a big part of our stories.”

The Delaware Canal was an integral and instrumental part of the coal industry back in the 19th century. Damages caused by leaks and floods created vast maintenance problems, making general upkeep of the canal a never-ending task. These hardships coupled with the intense competition of the railroad industry made the inevitable downfall of the canal system a reality, and the short-lived operation of the Delaware Canal as a means to transport goods became quickly outdated. However, the legacy of this pioneering transportation method lives on as a beautiful state park that thousands visit each year for walking, horseback riding, jogging, and biking.

Sources:

- “A Brief History of the Delaware Canal.” Friends of the Delaware Canal. 2007. <http://www.fodc.org/canal-history.html>.

- “Delaware Canal.” National Canal Museum. 2008. Pennsylvania Historical and Museums Commission and the Pennsylvania Humanities Council. 10 Nov. 2009 <http://www.canals.org/educators/curriculum/Delaware_Canal>.

- “Delaware Canal.” Scenic Bucks County. 2008. 10 Nov. 2009 <http://scenicbuckscounty.com/Canal/Canal.html>.

- “Float Boat History on the Delaware Canal.” Boston Globe 3 Sep. 2006, THIRD, Travel: M3.

- Jones, Chester L. The Economic History of the Anthracite-Tidewater Canals. Philadelphia: The John C. Winston Co., 1908.

- “Just Mention Canals, and Stories Flow \ Albright ‘zip’ Zimmerman Lives Near the Delaware Canal.” Philadelphia Inquirer 15 Oct. 2000, CNORTH, NEIGHBORS BUCKS: BC01.

- McMaster, John B. A History of the People of the United States, From the Revolution to the Civil War. Vol. 3. New York and London: D. Appleton and Company, 1921.

- Poor, Henry V. History of the Railroads and Canals of the United States. Vol. 1. New York: John H. Schultz & Co., 1860.

- Zimmerman, Albright G. Pennsylvania’s Delaware Division Canal Sixty Miles of Euphoria and Frustration. Calabasas, CA: Center for Canal History & Co., 2002.