A common picture of science laboratories involves a crazy chemist toiling away in a dark, smoke filled dungeon with flickering lights and vials and beakers stacked precariously, waiting to spill their hazardous contents. In his book Mad, Bad and Dangerous, Christopher Frayling describes one such lab, “At the climax of the Wizard of Oz, Dorothy and her three new friends…arrive at the Emerald City, to ask the great and powerful wizard for their hearts’ desires. The wizard’s workshop – full of lights, dials, jars, beakers and smoke – is like an emerald coloured version of Frankenstein’s laboratory.” Actual laboratories, however, are usually quite different.

The model for chemical laboratories in the United States was built by Dr. William H. Chandler at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Northampton County, in 1885. The Chandler Chemistry Laboratory is considered the first modern chemistry lab. Dr. Chandler designed a facility in which many chemists could train simultaneously, whereas in the past training was done through apprenticeships.

The need for more, better-trained chemists was due, in part, to the booming iron and steel industry of Pennsylvania at that time. The Chandler Lab met this need with an innovative style that would leave a lasting impression.

The Chandler Chemistry Laboratory not only influenced the steel and iron industry by providing well-trained chemists, it had a huge influence on the construction of future chemistry labs. Labs across the country used the ideas presented in the Chandler Lab to construct the most modern, efficient laboratories possible.

The National Research Council (U.S.) Committee on Design, Construction and Equipment of Laboratories published a book containing what it viewed as the necessary elements of a college laboratory in 1962, nearly 80 years after the Chandler Lab was built. The building itself should contain labs, lecture halls, stock rooms, and a library. All of these features were present in the Chandler Lab. Specific elements in the lab rooms included: water, gas, air, steam, oxygen and other gases, suction, ventilation and air conditioning, and electricity. Chandler’s lab provided all of the listed services except for air conditioning and electricity because it was built before these scientific achievements were made.

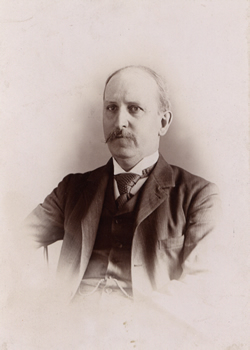

Dr. William H. Chandler was educated at Union College before being employed as an industrial chemist. He then received his Ph. D. from Hamilton College. He began teaching at Columbia along with his brother Dr. Charles F. Chandler, a famous chemist and teacher. The two edited a chemical journal, The American Chemist, a notable feature of chemical history.

Dr. William Chandler took a position at Lehigh University in 1871. His desire to improve chemical education, along with the need for better technically-trained chemists, led him to plan the designs for Lehigh’s new chemical laboratory. His designs were influenced by the laboratories of Justus von Liebig, at Giessen University in Germany, and Ira Remsen, at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. They were among the first scientists to emphasize teaching in a laboratory setting.

The Chandler Chemistry Laboratory was built from May 1884 to September 1885 from native Pennsylvania sandstone and cost $200,000 to construct, a monumental sum at the time. The building was designed by Chandler and Philadelphia architect Addison Hutton, “the Quaker Architect.” It was a T-shaped building with two main floors; a smaller third floor was located above the central portion of the building.

The main part of the lab (or the top of the T) measured 259 ft. by 44 ft., almost the length of three NBA basketball courts and a little less wide than one. The smaller south wing of the building was only two stories tall. The large size of the building allowed laboratories to be 44 ft. wide, more than double the size of the typical lab at the time. Usually labs were cramped and narrow, allowing only a few people to work in the crowded space. The improvement in size was one of the major contributions of the Chandler Lab because teaching chemistry could now be done on a larger scale, rather than in the more individualized apprenticeships of the past.

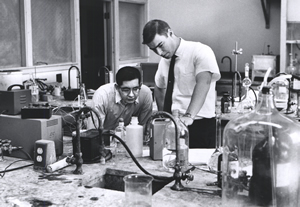

The Chandler Lab advanced laboratory design and became the basic standard for laboratory construction. The lab may be one of the first examples of modular bench use in a chemistry lab. These benches, built perpendicularly to the walls, were equipped with features such as: gas, steam, vacuum pumps, water, and compressed air. Linking these services directly to each station was a new idea at the time, but has since become the standard practice. Chemists can save much time and energy, as well as increase their safety, by having such services available at arm’s reach.

A very important design feature that allowed large labs to be built was improved ventilation. The laboratories were equipped with chimneys and fresh air intake systems at every window so that clean air was circulated into the lab while fumes from any reactions were removed via the chimney. To ensure that the fumes were expelled from the lab, the chimneys, which were coated with asphalt to prevent decay, were heated by steam to create an updraft of harmful gases.

According to the American Chemical Society’s Historic Landmark Site, along with its innovative laboratories, the Chandler building contained:

gold and silver bullion rooms; three balance rooms; two gas analysis rooms; three industrial chemistry rooms; photographic facilities; assay rooms; a room housing a steam engine; a library, lecture recitation and preparation rooms; a mineralogical laboratory; instructors’ and professors’ offices and laboratories, and space for agricultural chemistry, physiological chemistry, and sanitary chemistry.

It also contained speaking tubes for more effective communication between labs and centrally located stock rooms, both time saving features.

The capabilities of the Chandler Chemistry Laboratory were helpful in training chemists who would go on to affect local industries. At the time, the iron and steel industry was booming in Pennsylvania and chemists helped bring methods in the industry from a guessing game to an empirical science. Metallurgists knew the qualitative impacts of the main impurities in iron – carbon, manganese, sulfur, phosphorus, and silicon – but quantitative control of these elements came through the chemist. Chemical research into the effects of these elements on the iron and how to control their quantities led to the development of specific properties of different iron ores.

In the steel industry, according to Allerton Cushman, Director of the Industrial Research Institute, “the steel maker, in charge of the rapidly developing pneumatic processes, required to know and follow the content of carbon, manganese and other impurities during the progress of a heat. Analytical Chemistry came to the rescue by devising quick methods of analysis.” The chemist also contributed by devising ways to study and produce alloy steels using various elements such as: tungsten, chromium, vanadium, titanium, nickel, cobalt, molybdenum and tantalum. The Chandler Lab gave chemists the opportunity to learn and practice skills such as these.

For its innovative designs, the Chandler Chemistry Lab was awarded a design prize at the 1889 International Exposition held in Paris, France. The implications of the Chandler Lab were felt then and continued to be felt for decades to come. According to the American Chemical Society, “the building set the standard for laboratory construction for the next half century.” Based on this influence, the Chandler Chemistry Laboratory was honored as a National Historic Chemical Landmark in 1994 by the American Chemical Society.

Additions were made to the lab in 1921 and 1938. First a three-story west wing was added and then a much larger east wing was constructed under the supervision of H.M. Ullman. This large east wing housed research and general chemistry labs as well as the chemical engineering labs. The new, larger building was updated in 1957 with new plumbing and wiring and was later renamed the Chandler-Ullman Laboratory.

In 1975, a new chemistry laboratory was built at Lehigh University leaving only the Center for Health Sciences to occupy the Chandler-Ullman lab. The lab has since been remodled for offices and classrooms but still houses a few small labs.

The Chandler Chemistry Laboratory housed chemists for over a century and was an amazing example of a modern chemistry lab. The influence of its design has left a legacy no other individual laboratory comes close to matching. Dr. Chandler was supremely proud of his innovative lab, as he should have been. His pride can be seen in a quotation from the Lehigh University yearbook, The Epitome, published in 1887, “Students wishing to take friends through the laboratory must make a deposit of fifty cents with Professor Chandler, to provide for wear upon the building.” With the improvements made to labs by Dr. Chandler through contributions like those, gone were the days of chemists toiling away in dark, dingy dungeons.

The Center would like to thank Ilhan Citak of Special Collections, Lehigh University Libraries for his assistance illustrating this article.

Sources:

- Billinger, R.D. “The Chandler Influence in American Chemistry.” Journal of Chemical Education. 16.6 (1939): 253-257.

- Billinger, R.D. “Seventy-Five Years of Chemistry at Lehigh University.” Journal of Chemical Education. 19.2 (1942): 82-85.

- “Chandler Chemistry Laboratory.” Content Portal. American Chemical Society, 2010. 10 Oct. 2010 <http://portal.acs.org/portal/acs/corg/content?_nfpb=true&_pageLabel=PP_A....

- Cushman, Allerton S., “Contributions of the Chemist to the Iron and Steel Industry.” Ind. Eng. Chem. 7.11 (1915): 934-935.

- Frayling, Christopher. Mad, Bad and Dangerous? The Scientist and the Cinema. London: Reaktion Books LTD, 2005.

- Holmes, Frederic L. “The Complementarity of Teaching and Research in Liebig’s Laboratory.” Osiris. 2.5 (1989): 121-164.

- Hyde, E.M. The Lehigh University: A Historical Sketch. South Bethlehem, PA: Lehigh University Alumni Bulletin Publishers, 1896: 32, 41, 54. 14 Oct. 2010 <http://www.lehigh.edu/library/speccoll/hyde.pdf>.

- “Images – Science and Education.” German History in Documents and Images. German Historical Institute. 15 Oct. 2010 <http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/sub_image.cfm?image_id=2278>.

- National Research Council (U.S.) Committee on Design, Construction and Equipment of Laboratories. Laboratory Planning for Chemistry and Chemical Engineering. New York: Reinhold Pub. Corp., 1962.