When Thomas Paine wrote that “These are the times that try men’s souls,” he embodied the spirit of the hopeless situation George Washington, his soldiers, and supporters of the Patriot cause were facing in December 1776. In need of fresh troops and funds, Washington found himself in a desperate state. Continental soldiers served for a calendar year, and Washington was about to lose a majority of his troops on December 31, 1776. After being defeated by British troops multiple times in the previous months, financial donors and military volunteers were apprehensive about supporting a losing cause. George Washington needed to win the war immediately or accept defeat.

Washington succeeded at the Battle of Trenton on December 25, 1776 when the Patriot Army defeated the Hessians. Washington chose to sail across the Delaware River on Christmas night from what is now called Washington’s Crossing, Pennsylvania to Trenton, New Jersey while the Hessians slept after eating and drinking to celebrate the holiday. When asked about his thoughts on Washington’s daring move, Stephen Willey, president of the Durham Historical Society, vividly exclaimed, “Washington had a Hail Mary. He needed to win this battle or the war was over.” To obtain a victory, the Washington Crossing Historic Park notes that Washington wrote Governor William Livingston of New Jersey requesting him to secure Durham boats for the voyage.

Originating in the small Bucks County town of Durham, Durham boats were significant because of their flat- bottomed design. In shallow, Eastern waters this allowed for the carrying of large loads of cargo, including troops. Measuring sixty-six feet long, six feet wide, and three feet deep; these boats held up to seventeen tons while only displacing twenty inches of water. They were double-ended, meaning they were sharp at both the bow and the stern, allowing for swifter navigation. Forty soldiers comfortably fit in the Durham boat, along with their equipment and a crew of six men to propel the vessel. Crew members used oars along with a steel pole that would be dug into the river bed, while one crewman held the opposite end against his shoulder as he walked from the bow to the stern. This was the most efficient way to navigate the waters.

In its original function, the Durham boat was used daily to support the Durham Furnace. Established in 1727, the furnace was located in a region rich in timber and iron. This allowed for the creation of steel that was used to make a variety of products, including Franklin Stoves, for the people of Bristol and Philadelphia. All goods of the furnace were transported on Durham boats. At its peak, there was a fleet of one thousand Durham boats sailing the Delaware River, employing thousands of men along the way. A trip from Durham to Philadelphia was a swift and downstream voyage, taking only a day to complete. The return trip was more difficult going against the current and required increased effort from the crew. During the Revolutionary War, the Durham Furnace began to produce cannon balls, or “shot,” for the Continental Army.

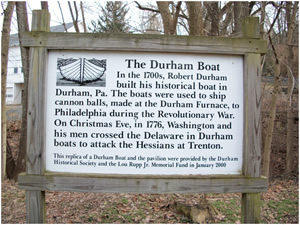

The origin of the Durham boat is surrounded in much controversy. According to the Durham Historical Society, some Bucks County historians such as W.W.H. Davis and J.H. Battle claim the Durham boat was created by Durham Furnace employee Robert Durham around 1730 in Durham, Pennsylvania. These men base their stance on the written paperwork left by B.F. Fackenthall, Esq., a Durham native, who recorded Robert Durham as a boat builder by trade. Others, such as historian Richard H. Hulan, argue that the boat has ties to the Church boat and Rapids boat of Scandinavia which were used to transport immigrants to Pennsylvania and to transport cargo in the Swedish iron industry. Hulan contests that both Swedes and Finns were the boatmen during this period of time and were skilled boat builders. They also were in the business of transporting people and goods along the waterways. Hulan also claims there was no record of Robert Durham being an employee of the Durham Furnace and there is no way an English foundry man had the knowledge or skills available to engineer such a sophisticated boat. In response to these allegations, Stephen Willey joined the majority of Bucks County historians in his belief that Robert Durham “was the real deal.”

Even with the Durham boat’s sturdy construction and unmatchable craftsmanship, the crossing of the Delaware River would not have been possible without an expert crew to navigate George Washington and his boat through the icy waters of the Delaware River. Patriot soldiers from Marblehead, Massachusetts under the command of John Glover met these vital criteria. Author Ann Hawkes Hutton discusses the skills and perseverance of these professional fishermen in her book, “George Washington Crossed Here.” Together, these men loyally followed Washington from the Battle of Brooklyn, through Manhattan, and finally to New Jersey. As a testament to their courage Hutton writes, “The crossing had looked too difficult to several of the other generals who had agreed to make the crossing that night…But General Washington crossed!” The men of Marblehead, Massachusetts put their knowledge of dangerous waters to use as they expertly navigated their way from the shores of Pennsylvania to Trenton, New Jersey in the Durham boats.

Though taking place so long ago, the monumental night of December 25, 1776 can be visualized by most Americans today thanks to painter Emanuel Leutze. The crossing of the Delaware River was depicted in his famous painting, “Washington Crossing the Delaware,” in 1851, but the Durham boat was not. The boat shown is much smaller in length and width than a true Durham boat. A Durham boat was capable of carrying more soldiers than are shown in the painting as well. Since Washington had to transport all of his men across the river, he would have used the boats to their full capacities. On average, a Durham boat would displace only twenty inches of water when fully loaded. In the painting, the boat is nearly completely submerged in the water. Despite its inaccuracies, this painting is a vital part of American culture and is in the permanent collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

In time, the creation of the Delaware canal system in 1832 and the use of canal boats phased the Durham boat out of use. Canal boats were created to navigate the shallow waterways more efficiently than the Durham boat due to its slender and long design. Canal boats were still capable of carrying large amounts of freight while displacing minimal amounts of water. The canal system and boats lost popularity to a more efficient steam boat around the turn of twentieth century. Steam boats were larger and deeper than canal boats, which allowed for larger loads and faster travel. Due to sheer size, these boats could not travel along the canal system. Despite its replacement as a means of transportation, the Durham boat continues to be used in the present day by historical re-enactors of the crossing.

Today, Washington’s crossing of the Delaware River is re-enacted by local volunteers. These men dress in time- appropriate garb and make the courageous crossing in Durham boat replicas every Christmas Day to honor this momentous event. Once hosted by the Washington Crossing Historic Park, as of 2009, the Bucks Conference & Visitors Bureau organized this event due to cuts in the state budget. The Bucks Local News re-enactment boasted both a dress rehearsal and colonial encampment in addition to the Christmas day crossing where thousands of visitors flock to the county. In 1947, a Durham boat was constructed in Maine for the re-enactors of the crossing. The boat was used in the crossing every year until 1989 when a dispute between the re-enactors and the Washington Crossing Historic Park broke out as to who was the rightful owner. The Durham Historical Society stepped in and placed an offer on this replica; purchasing the boat at a large discount. They placed the boat on display next to the Durham Post Office and mill which once served as the Durham Furnace.

From its original function as a transporter of steel products, to a carrier of cannon balls during a time of war; the Durham boat was a faithful vessel for the products of the Durham Furnace. Making the daily journey from Durham to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, it built a reputation of quality and reliability along the way. In 1776, it transported its most precious cargo to date: George Washington and his soldiers. Through the craftsmanship of the Durham boat, the skill of the crewmembers, and the courage of the soldiers, American freedom became a reality as the Patriot army sailed across the Delaware River on Christmas night to defeat the Hessians. As time passed, this noble voyager was replaced by more modern and efficient boats and its use became purely ornamental. To this day, the Durham boat is proudly displayed in Durham, Pennsylvania for all to see and be admired for its significance in American history.

Sources:

- “The Chesapeake & Delaware Canal.” US Army Corps of Engineers. 13 Apr. 2010. <http://www.nap.usace.army.mil/sb/c&d.htm>.

- The Durham Boat. Washington Crossing Historic Park. 20 Jan. 2010. <http://www.ushistory.org/washingtoncrossing/history/durham.htm>.

- History of The Durham Boat. Durham Historical Society. Durham Historical Society. 20 Jan. 2010. <http://durhamhistoricalsociety.org/history2.html>.

- Hutton, Ann Hawkes. George Washington Crossed Here. Philadelphia: Franklin Company, 1966.

- Leutze, Emanuel Gottlieb. Washington Crossing the Delaware. 1851. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Met Museum. 24 Feb. 2010. <http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/97.34>.

- Ward, Christopher. The War of the Revolution. Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky, 1952.

- Werner, Jeff. “Oarsmen Navigate Swift Currents, Biting Winds in Prelude to Washington’s Historic Crossing.” Bucks Local News. BucksLocalNews.com. 7 Dec. 2009. 18 Apr. 2010. <http://www.buckslocalnews.com/articles/2009/12/07/the_advance/news/doc4b....

- Willey, Stephen. Personal Interview. 29 Jan. 2010