Norm Adam’s appearance and biography aren’t anything out of the ordinary. He is a native Pennsylvanian, having spent his whole life in Kutztown. He is typical—a white, American male, over the age of 50, living his whole life in a rural, but developed and relatively affluent area of the country. Then he opens his mouth. Though Norm Adam is a native English speaker, to the untrained ear, his accent and vocabulary are so foreign that he is hard to understand. Norm is a Pennsylvania Dutchman, or Pennsylvania German.

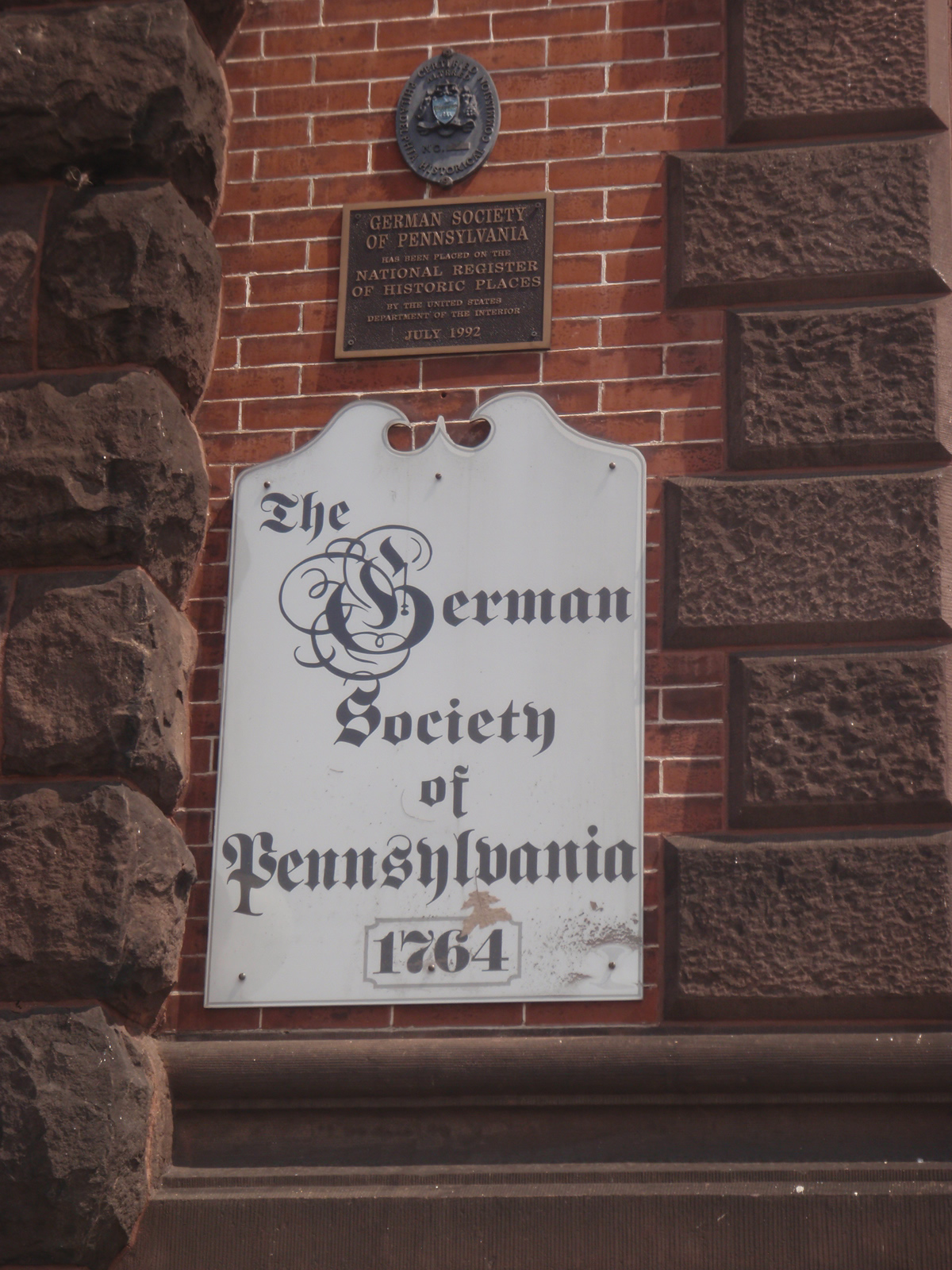

Despite his cultural and linguistic idiosyncrasies, Norm is not an anomaly in Berks County. German immigrants came to Pennsylvania in 1683 and settled in the appropriately-named “Germantown,” now a section of Philadelphia. As Pennsylvania grew, more Germans came to the colony and more them pushed further inland, settling in Berks and Lehigh counties in the 17th century. Many of their descendants, like Norm Adam and his family, still live there today. Over the past several decades, the usage and maintenance of the Pennsylvania German language among non-sectarians, people who are not Amish or Mennonite, has drastically dropped. But, as the population of secular, native Pennsylvania Dutch speakers ages, people like Norm are becoming rarities. The history of the Pennsylvania Germans is integral to the history of the state of Pennsylvania, and with the loss of their dialect comes a loss of part of the state’s history.

When people from outside Berks and Lehigh counties hear “Pennsylvania Dutch,” they usually think of the Amish and Mennonites—old order sects of Anabaptists that separate themselves from modern society. They picture horses and buggies, bonnets, and beards. But “Pennsylvania Dutch” is not necessarily synonymous with “Amish.” Rather, the Amish and Mennonites, or “Plain” Dutch, and the non-sectarians, or “Fancy/Gay” Dutch form two separate subcultures within the broader Pennsylvania German heritage.

Traditionally, both the Anabaptists and the non-sectarians have spoken their own dialect, a combination of the German of the Rhenish Palatinate and English, called Pennsylvania German, or Pennsylvania Dutch. The “Dutch” part does not refer to people from Holland, but is an English adaptation of Deutsch, the German word for “folk.” Though rooted in German, the Pennsylvania German that exists today is so different from Modern German that the two are not mutually intelligible. As studies by Buffington show, the original German settlers in Pennsylvania did not all speak the same dialect. However, through a process of blending over time, these diverse dialects evolved into the now fairly homogenous Pennsylvania Dutch language. These differences can be seen in pronunciation, morphology and syntax. For example, in Modern German the first four lines of the Lord’s Prayer are:

Vater unser im Himmel,

Geheiligt werde dein Name,

Dein Reich komme,

Dein Wille geschehe.

The Pennsylvania Dutch translation of the same four lines is:

Unsah Faddah in Himmel,

Dei nohma loss heilich sei,

Dei Reich loss kumma

Dei villa loss gedu sei.

Aside from the vocabulary differences (the German vater is, in Pennsylvania Dutch a German-English sounding faddah), there are also syntactical differences. The second line, for instance, in German translates one-to-one in English: Hallowed be thy name. In Pennsylvania Dutch, though, it translates literally to “thy name let hallowed be.” This passive construction, while permissible in standard German, is atypical of the mother tongue.

Additionally, after arriving to Pennsylvania, many German immigrants encountered objects and concepts for which they did not have words. This linguistic process of “convergence,” what Fuller describes as an “adoption of lexical and structure features from one language to another,” had its effects on Pennsylvania German and the English of both Pennsylvania Dutch and non-Pennsylvania German speakers, as studies by Huffines, Kloss, and Kopp also show.

The new “Dutchified” words that developed were combinations of German and English words, and continue to give Pennsylvania Dutch its unique linguistic character, distinguishing it from both German and English. A modern example is the Pennsylvania German word for “television,” gookbox. While the German word is Fernsehen, the Pennsylvania German word literally translates as “look box,” and is most likely an adaptation of the German word gucken and the English word “box.”

However, the language influence is not one-sided. While English affected (and continues to influence) the development of Pennsylvania German, Pennsylvania Dutch also affects the English of its speakers, and even non-speakers who live in areas like Berks and Lehigh Counties where the dialect’s influence has been historically strong. For example, as studies by linguist Michael Adams have shown, many lexical and syntactical idiosyncrasies, such as using the word “yet” to mean “still” as in, “Are you living at home yet?” are common. Additionally, distinctive syntactical differences, such as saying “Outten the light” for “Turn the light off” remain unique to people living in the Berks and Lehigh Counties.

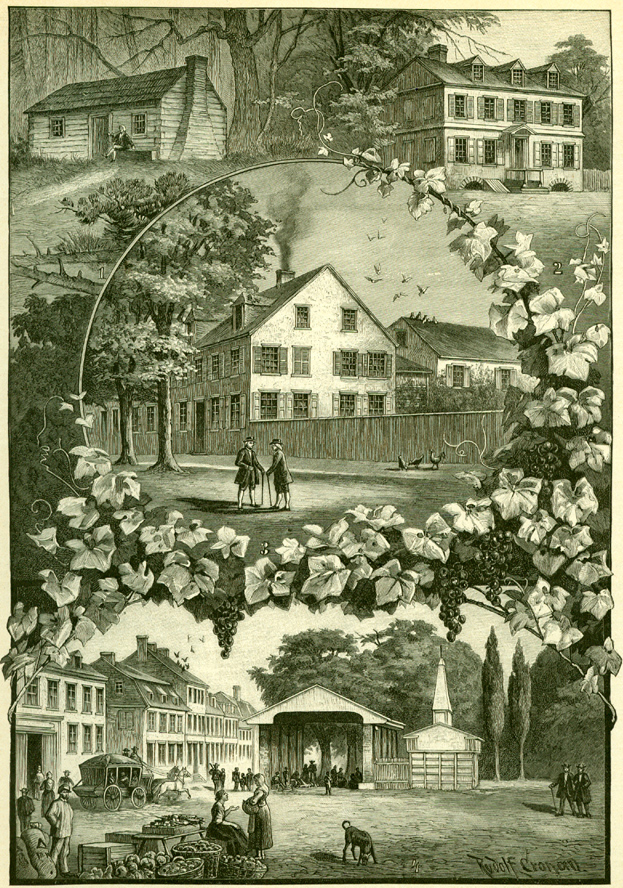

Ralph Wood, one of the most respected historians of Pennsylvania German, describes the history of the Pennsylvania Germans, and their importance to Pennsylvania’s history. In Pennsylvania’s early settlement, founder William Penn needed more settlers. Because of their similar religious convictions and state of persecution, German Anabaptists and reformists were attractive candidates for Penn, a Quaker. By 1727, Pennsylvania’s reputation as a haven for German immigrants was so strong that Germans ignored most of the recruitment of other colonies.

In the year 1749 alone, more than 6,000 emigrants from German states found home in America. The German settlers, by many early accounts, were superior farmers, and thus contributed largely to the success of the colony, particularly in the French and Indian War, thanks to their prosperous farming communities. Despite their numbers and tightly-knit communities, Pennsylvania Germans began to assimilate soon after immigrating, largely because of governmental regulations. In 1727, for instance, England passed a law that forced all “foreign” settlers in the British colonies to pledge an oath of allegiance to the British crown. After the Revolution, Pennsylvania Germans were no longer foreigners; they were Americans with social freedoms, and thus assimilated even more.

With this process of assimilation, the language began to change, and fewer people learned to speak it. Though the language remains intact among Amish and Mennonite communities, non-sectarians like Norm Adam are no longer using or even speaking Pennsylvania Dutch. Though Norm was raised speaking both English and Pennsylvania German, he is the only member of his immediate family who speaks the dialect. “I feel so guilty about it,” Norm says, “I didn’t teach either one of my children.”

Norm Adam’s case is not rare. In fact, he follows a trend common to almost all non-sectarian Pennsylvania German speakers. As studies by Huffines, Louden, Williamson, and other linguistic scholars have shown, the vast majority of secular fluent Pennsylvania Dutch speakers are over the age of 50, and have not passed the language to their children. The language is dying, and quickly among the non-sectarians; it continues to thrive among sectarian Germans.

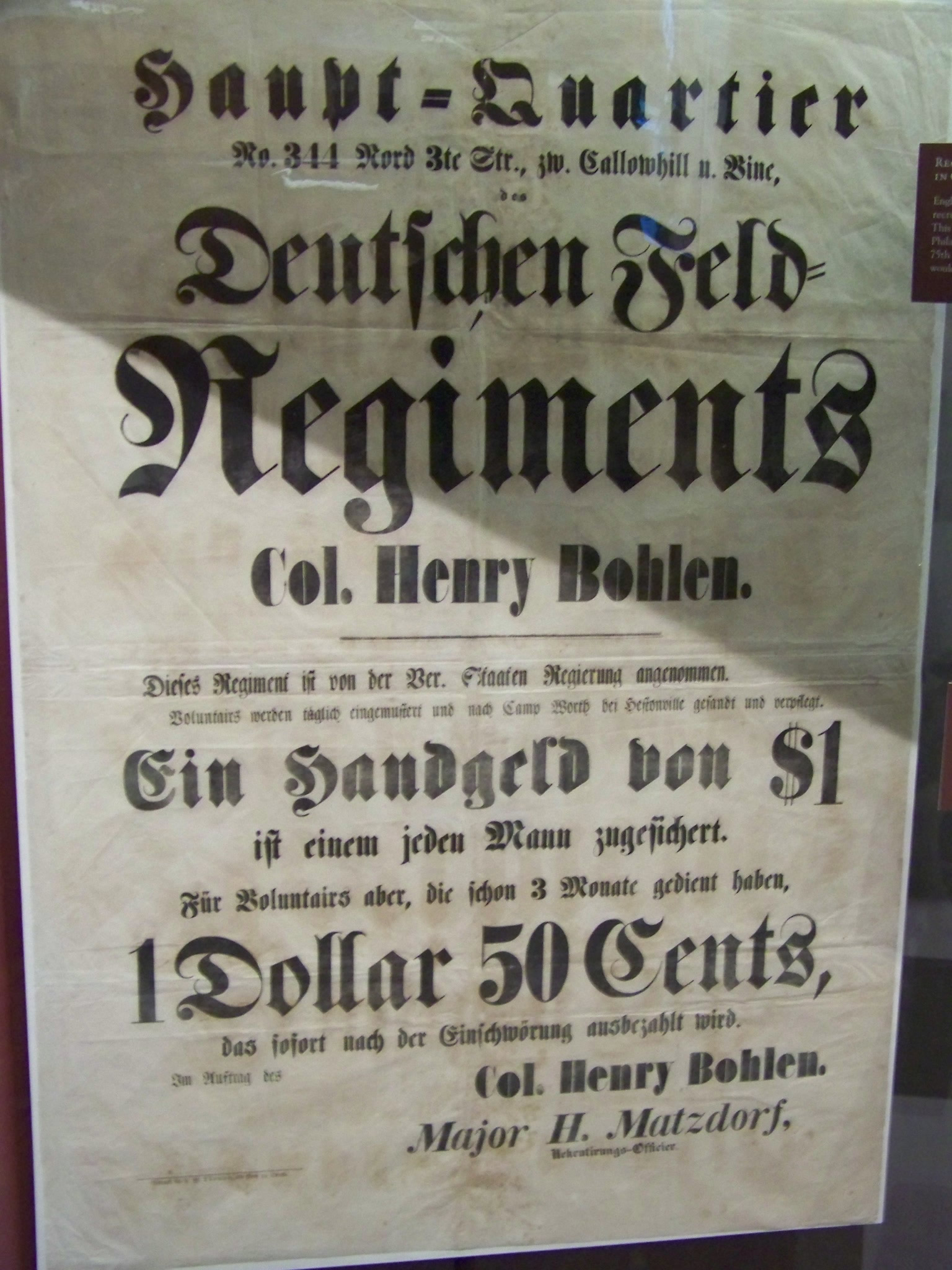

Why is the language disappearing so rapidly, particularly in the last 50 to 60 years, among non-sectarians? As a minority language in an English commonwealth, was Pennsylvania German doomed from the start? To better understand the language’s decline, it is useful to examine the origins of Pennsylvania German assimilation. A great deal of Pennsylvania Dutch assimilation solidified in the 1800s. With the development of state-organized education, and legislature regarding mandatory attendance, Pennsylvania German children began to stop attending German-only or bilingual schools. Though, according to Wood, over 75% of Pennsylvania Germans were literate (higher than the national average at this time), many people saw the Pennsylvania Germans’ lack of English-speaking abilities as a sign of stupidity. The stigma of the “Dumb Dutchman,” which played a large role in later years, was born. Seeing a problem with the Pennsylvania German language and subculture, the state said, in 1857, that the “language problem” would only be solved with time. At a time when language was a symbol of patriotism, the existence of non-English speaking groups threatened preconceived ideas of national identity. Add to this the social and geographical movement that the Civil War imposed on families and soldiers, and the reasons for more assimilation make sense. In 1911, the state passed a law requiring English to be the only language of public school instruction.

Though the state passed laws stipulating the use of English, according to Wood, it did not adequately provide for Pennsylvania German children in public schools who did not speak English as a native language. The means of enforcing the English-only law became ridiculing the dialect. Teachers told children who could not communicate in school to, “Speak English.” Not only did this result in several generations who did not receive quality education, but also it aggravated the pre-existent stereotype of the “Dumb Dutchman.”

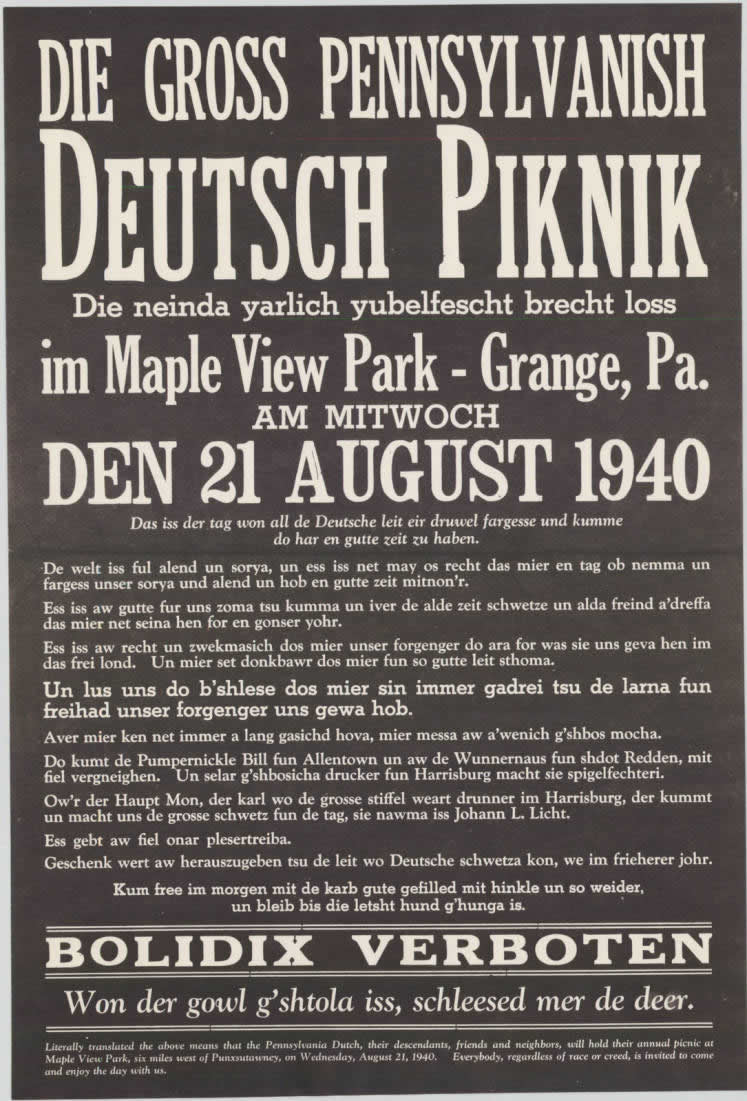

While this early tradition of assimilation had its effects on the usage of Pennsylvania German, at home and family or community situations, the dialect remained intact. The time between the two World Wars presents a tension in the possible reasons for the continued decline of Pennsylvania German. In fact, during this time, a paradox emerges from both the climax of Pennsylvania German cultural production, and the anticlimax of the language’s usage. A common thought, especially among Pennsylvania Germans, is that anti-German sentiment contributed heavily to the language’s disappearance.

Lynn Boyer, a native Pennsylvania German speaker from Berks County, has strong memories from this time. “I remember being called a dirty kraut in school,” Lynn says. “We and our neighbors were persecuted for sounding German.” This theory of anti-German sentiments contributing to the death of Pennsylvania German is not without grounds. Historians, like Kloss, reinforce Lynn Boyer’s conclusions, discussing how many states prohibited the use of German (and Pennsylvania German) at meetings, over telephones, and in the street. People known for “pro German activities” faced mob persecution that sometimes resulted in tar and feathering, whipping, and public humiliation. The very real memories of humiliation as an adolescent have carried throughout Boyer’s life. “If you sounded like a German, they thought you were a Nazi,” Lynn says, “So we tried to cover our accents.”

Scholars like Huffines and Louden acknowledge that anti-German feelings during the wars existed, and that this xenophobia might have contributed to Pennsylvania German speakers feeling ashamed of their dialect. Yet because of the paradoxical flourishing of Pennsylvania German cultural products during this period, scholars also feel that the anti-German sentiment explanation is not entirely sufficient. During the time between the two World Wars, Pennsylvania German literature (such as Edith Thomas’ poems and George Frederick’s culture and history books), cultural clubs (like the Groundhog Lodges), and efforts to maintain the language were at an all-time high. These facts push scholars to look for other explanations for the language’s gradual decline.

Linguists Enninger and Springer, agree that geographical mobility, often brought by the wars, and continued stereotypes of the “Dumb Dutchman” contributed most significantly to the disappearance of Pennsylvania German within the last century. Not only did many Pennsylvania Germans enlist as soldiers during the two World Wars, and so come in contact with people who did not speak the dialect, but also, the effects of the war enabled people to leave their farms in Berks and Lehigh Counties, and move elsewhere. The post-war G.I. Bill enabled many Pennsylvania Germans to obtain college educations, thus removing them from the concentrated areas of Pennsylvania Dutch culture in which they grew up.

Many Dutchmen and women left their farms and relocated, often marrying non-Pennsylvania Germans. These new cultural situations worked to lessen the diglossic state of Pennsylvania German. Linguists argue that when two languages exists simultaneously, but do not have separate and equally valid spheres of usage, speakers will invariably choose one language over the other. As Pennsylvania Germans left the isolated areas of Berks and Lehigh counties, they also were leaving the social situations that required them to speak Pennsylvania German. Without this requirement, for the sake of practicality and convenience, they began to use English, and forget Pennsylvania Dutch.

If geographic mobility provided the opportunity for Pennsylvania Dutch to decline, the “Dumb Dutchman” stereotype provided the motivation. Norm Adam, more than a decade younger than Lynn Boyer, vividly remembers this phenomenon. “I believe there was a stigma, because people thought of you as not intelligent when I was in high school. Even some of my teachers made fun of me,” Norm says of his experiences with the “Dumb Dutchman” stereotype. “When I was in the navy, I got poked fun of a lot—I wasn’t mature enough to be proud of my accent. I actually tried to get rid of it.” Like many Pennsylvania Dutch speakers, Norm decided not to teach his children the language. “We didn’t want our kids to be poked fun at either,” Norm says.

Lynn Boyer also remembers feeling like a “Dumb Dutchman” during school. “I had problems with English,” Boyer remembers. “I would say things like ‘Make the light out,’ and my sentence structures would be wrong because of German. Sometimes I got made fun of, but I was a scrappy person, so they got bloody noses from me.”

The phenomenon that Norm and Lynn describe is consistently the process that scholars like Fishman, Fuller and Kopp, who study the language’s disappearance are finding. Pennsylvania German speakers in an increasingly delocalized society were ashamed of their accents and unique way of speaking. Because they didn’t want Pennsylvania Dutch to interfere with their own children’s English or social lives, they did not pass the language to the next generation.

These factors also help to explain the stark difference between language maintenance among non-sectarians versus maintenance among Amish and Mennonite communities. Though English is primarily the language of schooling and outside business for Amish and Mennonite communities, the language of home, church, and all in-group social relationships is Pennsylvania Dutch. Because these sectarian communities are sequestered, there remains a very strong diglossic state, and all age groups in the community speak the language equally well. Generally, Amish and Mennonite communities and “Gay Dutch” communities rarely overlap. However, with the recognized disappearance of Pennsylvania Dutch among non-sectarians, some non-Sectarians nostalgically seek communication with Amish and Mennonites.

Norm Adam talks of how his knowledge of Pennsylvania Dutch has been a positive influence on relationships with Amish and Mennonite communities. Because Anabaptist groups separate themselves from mainstream society, there are often legal problems that occur between non-sectarians and sectarians, especially where land regulations and codes are concerned. “When I was on the board of supervisors for the township,” Norm says, “We would sometimes run into problems with the Amish, and no one would want to negotiate. If you speak Pennsylvania Dutch with the Amish, though, you’re in with them and they are willing to bend a little more and conform to some of the rules.”

As the population of native non-sectarian Pennsylvania Dutch speakers continues to age, the prospect of the language’s eventual extinction has become alarming, both to members of the Pennsylvania German community and to linguists. Practically, a language is a tool—and when it loses its utility, it is rational for it to disappear. Yet on a more culturally sensitive level, the death of a language is disconcerting. According to Ken Hale, a cultural linguist, language loss is serious because it also entails the loss of cultural and intellectual diversity. Hale compares this loss to the loss of biological diversity, arguing that language diversity is important to human intellectual life and the “priceless product of human mental industry.”

Words that have no equivalent in English or German are lost and expressive capability diminishes as the Pennsylvania German language dies among those in the non-sectarian community. For example Pennsylvania Dutch’s word schlecky—an adjective that describes foods that are sickeningly sweet, rich, fatty, or all three— as in “I can’t eat any more of that cake, it’s too schlecky,” has no English or German equivalent to really convey the speaker’s meaning. Such terms are generally maintained by the Old Order Amish and the Old Order Mennonites who still speak the language, but interact less with the English speakers.

Like groups in Ireland, Wales, and other places facing similar situations, members of the Pennsylvania Dutch community have reacted by rallying to create local maintenance efforts. The Kutztown University Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, for instance, offers Pennsylvania Dutch language courses and cultural activities both to students and community members. Folk festivals, dialect concerts, and associations, like Groundhog Lodges (clubs that hold meetings in Pennsylvania Dutch and organize cultural events) have also been popular in Berks and Lehigh Counties.

“I believe that today people respect anyone who is bilingual, so the stigma of being a Dumb Dutchman isn’t there anymore,” Norm Adam says. “Now that we’re older and more mature, we don’t care as much what people think of us and we’re trying to keep the dialect alive. Now I’m proud of my accent.”

But these preservation efforts present their own problems. Often, efforts to preserve the language by attracting the attention of tourists have discredited the language and culture, contributing to the “Dumb Dutchman” stereotype. Books like Gates’ How to Speak Dutchified English and comedy performances that urge audiences to, “Come and hear a hilarious talk on the funniest regional accent, Pennsylvania Dutch!” (The “Dutchified English” performance at the Kutztown Folk Festival) mock and minimize the culture. Even Pennsylvania Dutch jokes tend to be self-consciously aware of the Dumb Dutchman stereotype and play upon it. Alfred Shoemaker’s My Off Is All: A Treasury of Pennsylvania Dutch Humor writes,

“Dutch-English jokes poke fun, good-naturedly of course, at the way the Pennsylvania Dutch talk. Who has, for instance, not heard of the college freshman who comes home to spend the Christmas holidays on the farm? His parents meet him at the railroad station. ‘Well John,’ they say, ‘what have you learned at college?’ And John answers, ‘Why, before I went away to school I used to sound awfully Dutchy; I used to say NORSE and SOUSE, but now I can say BOSE correct.’”

Also, though some non-Pennsylvania Dutch speakers take classes, they rarely attain the level of native speakers, because there just aren’t very many places to practice and use the language.

Though the dialect may remain as an historical artifact of Pennsylvania, its future is almost certain—with the passing of its native speakers, it will become, at least among non-sectarians, a phenomenon of the past. Perhaps, though, efforts to preserve the language will help to protect its legacy.

“It’s important to preserve any kind of history,” Norm says, “and most of your Pennsylvania Dutch people are really hardworking, honest people who care about others. It’s part of our culture. I’ll probably try to teach Pennsylvania Dutch to my granddaughter, but it won’t be like it was fifty years ago,” Norm Adam says. “People will still use the words, but the accent won’t be there. People who have the accent are getting older, and with them, it will die. And I helped to let it die. And I’m ashamed of that part.”

The Center would like to thank Dr. Richard Page of Pennsylvania State University for his assistance with this article.

Sources:

- Adams, Michael P. “About ‘Like’ in Berks County, Pennsylvania.” American Speech Winter 68.4 (1993): 439-40.

- Adams, Michael P., and Newton A. Perrin. “Unless ‘In Case’ in Berks County, Pennsylvania.” American Speech Winter 70.4 (1995): 441-42.

- Buffington, Albert F. “Similarities and Dissimilarities between Pennsylvania German and the Rhenish Palatinate Dialects.” Four Pennsylvania German Studies. Vol. 3. Breinigsville, PA: Pennsylvania German Society, 1970. 91-116.

- Enninger, Werner. Studies on the Languages and the Verbal Behavior of the Pennsylvania Germans. Stuttgart: Steiner, 1986.

- Fishman, Joshua A. Language Loyalty in the United States; the Maintenance and Perpetuation of Non-English Mother Tongues by American Ethnic and Religious Groups. The Hague: Mouton, 1966.

- Fuller, Janet M. “When Cultural Maintenance Means Linguistic Convergence: Pennsylvania German Evidence for the Matrix Language Turnover Hypothesis.” Language in Society Dec 25.3 (1996): 493-514.

- Gates, Gary. How to Speak Dutchified English. Intercourse, PA: Good, 1987.

- Hale, Ken. “On endangered languages and the Safeguarding of diversity.” Language Mar. 68.1 (1992): 1-3.

- Hale, Ken. “Language endangerment and the human value of linguistic diversity.” Language Mar. 68.1 (1992): 35-42.

- Huffines, Marion L. “The English of the Pennsylvania Germans: A Reflection of Ethnic Affiliation.” The German Quarterly Spring 57.2 (1984): 173-82.

- Huffines, Marion L. “Pennsylvania German in Public Life.” Pennsylvania Folklife Spring 39.3 (1990): 117-25.

- Kloss, Heinz. 1966 “German-American Language Maintenance Efforts.” In Fishman, Joshua A. (ed.) Language Loyalty in the United States, 206-252. The Hague: Mouton.

- Kopp, Achim. The Phonology of Pennsylvania German English as Evidence of Language Maintenance and Shift. Selinsgrove, PA: Susquehanna UP, 1999.

- Louden, Mark L. “Minority-Language “Maintenance by Inertia”: Pennsylvania German among Nonsectarian Speakers.” “Standardfragen“: Festschrift Fur Klaus J. Mattheiser. 2003. 121-37.

- “Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center.” Welcome to Kutztown University -- College of Visual and Performing Arts, College of Education, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, College of Business, Office of Graduate Studies. Web. 13 Sept. 2010. <http://www.kutztown.edu/community/pgchc/index1.htm>.

- Shoemaker, Alfred L. My Off Is All! Lancaster: Pennsylvania Dutch Folklore Center, 1955.

- Springer, Otto. “The Pennsylvania Germans.” American Speech Apr 19.2 (1944): 130-34.

- Williamson, Robert C. “The Survival of Pennsylvania German: A Survey of Berks and Lehigh Counties.” Pennsylvania Folklife Winter 32.2 (1982-83): 64-71.

- Wood, Ralph Charles, and Arthur D. Graeff. The Pennsylvania Germans. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1942.

- Yoder, Don. The Pennsylvania German Broadside: a History and Guide. University Park, PA: Penn State UP for the Library of Philadelphia and the Pennsylvania German Society, 2005.