On January 22, 1959 a tragedy so corrupt and catastrophic occurred at the River Slope mine in Port Griffith, Pennsylvania that it changed the future of the Anthracite coal industry forever: The Susquehanna River had ruptured the mine. “I no more than put my foot in the place and looked up then the roof gave way. It sounded like thunder. Water poured down like Niagara Falls,” testified John Williams.

The River Slope Mine, whose walls and ceiling were adjacent to the Susquehanna River, had been quarried without the required benefit of surface boreholes to determine the thickness of the rock cover and without proper surveying. Despite the fact that the Federal, State and County authorities discovered these safety concerns months earlier and ordered all digging in this particular vein to stop, the Knox administration nevertheless instructed mineworkers to keep digging at an upward angle towards the river bed. Although the minimum width of land recommended between the mine and river was 35 feet, the walls had been excavated to an estimated 19 inches from the raging Susquehanna.

The River Slope Mine, under the ownership of the Knox Coal Company, was one of many to be found in the Northern Anthracite coal field during the flourishing mining era. After a significant rise in temperature over a few days preceding the incident, the Susquehanna River began to thaw and climb to a staggering twenty-two feet on January 22nd. Eighty-one men, all of whom worked for The Knox, Stuart Creasing, and Pennsylvania Coal Companies, arrived ready to work on this seemingly normal day. Six of these men were sent to the Pittston vein in the River Slope Mine, while the rest were dispersed to the interconnecting May shaft.

At approximately 11:20 a.m., two laborers in the Pittston vein heard a sharp “popping.” They quickly called upon John Williams, the assistant foreman. The three employees hurried to escape and notify superintendant Robert Groves, who immediately ordered an evacuation, although he withheld the severity of the situation. Unfortunately, the other three men who were stationed in this vein could not escape in time and the fierce waters of the Susquehanna took their lives.

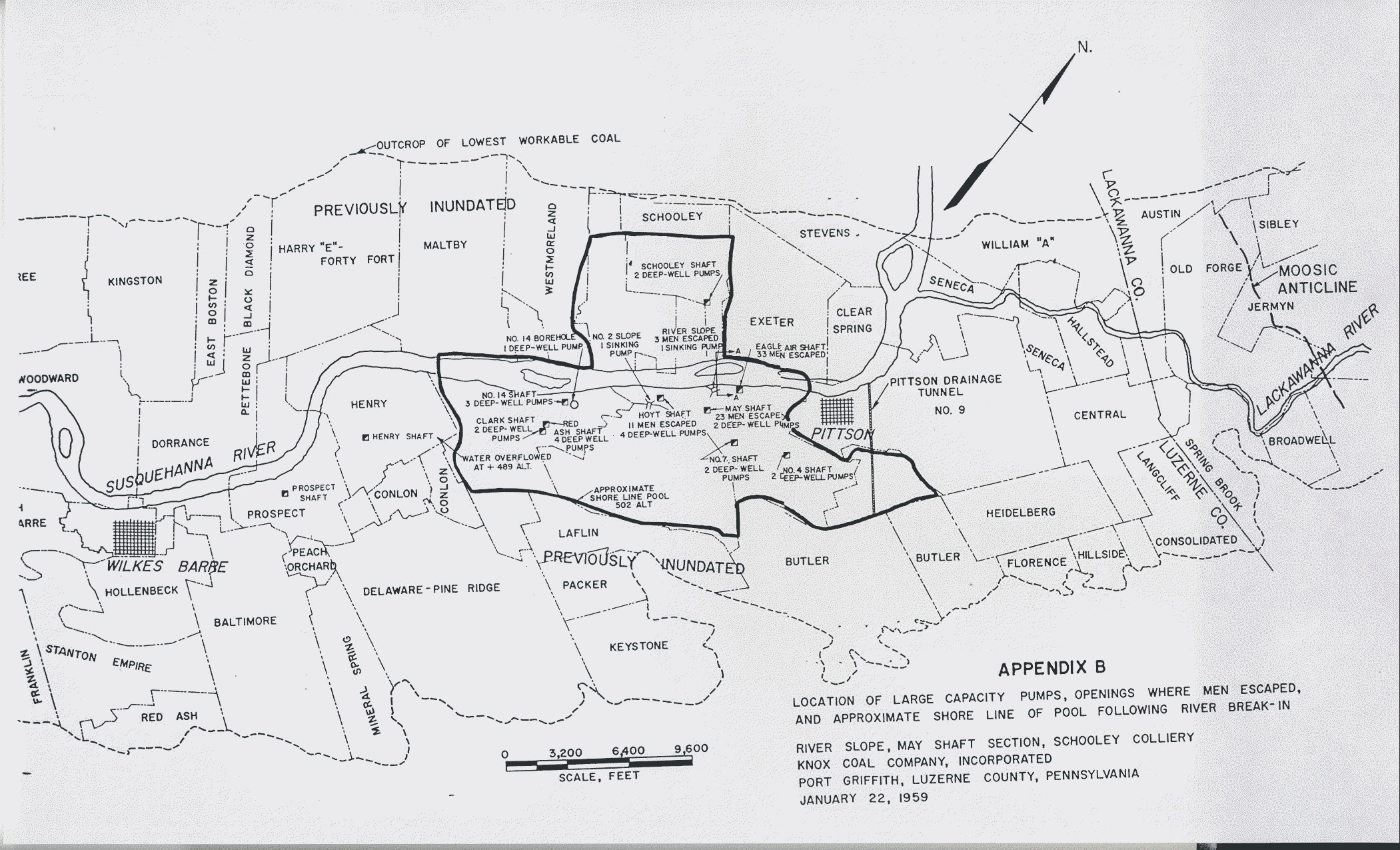

While millions of gallons of water flooded into the mine, thirty-three men managed to catch the last elevators at the May shaft, but forty-five others remained trapped, desperately seeking their own outlet. During the first sixty four hours of the emergency, an estimated 2.7 million gallons of water per minute streamed underground from an enormous whirlpool near the riverbank.

Up above, friends and family members gathered around the site and anxiously awaited the outcome of the men left behind. Many townsfolk wondered how long their husbands, fathers and brothers could survive without food, clean water and air. Rose Rynkiewicz remembers this frightening experience like it was only yesterday as she stood by with her mother and father while family members waited for their loved ones to emerge from the rocky destruction. She remembers comforting friends and neighbors while the community and members of nearby churches joined in prayer to hope for a miracle.

Down below, thirty-two men wandered in two separate groups until they managed to escape through the abandoned Eagle air shaft. Pennsylvania Coal Company surveyor, Joe Stella, led the first group of seven. He not only knew the mines well, but also possessed maps which allowed his group to find a direct course to the opening. The second group, led by Myron Thomas, consisted of twenty-five men who wandered for hours before they found their way to safety. Unfortunately, twelve of the original remaining bodies have ever been recovered.

The Pennsylvania Department of Mines and Mineral Industries began to pump water from the mine in hopes to save the adjoining veins and thus salvage what was left of the Anthracite Coal Industry. The state of Pennsylvania also covered the expenses of sealing the breach with sand and concrete to bring the total cost of recovery to an estimated five million dollars. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania presented bills totaling 1.5 million dollars to the Knox and Pennsylvania Coal Companies, but Knox paid nothing because it declared bankruptcy, and the Pennsylvania Coal Co. successfully argued that, as the lesser, it was not liable. The men at the top of the Knox administration as well as the Pennsylvania Coal Company were indicted with an array of charges such as mining and labor law violations, conspiracy and manslaughter. With the help of bribes and appeals none of the men were held responsible for the event that took place on that tragic day. However, the Knox men were convicted for income tax evasion and paid minimal fines, served minor jail sentences and probation.

Regardless of the actions of the common wealth, nearby mines were forced to close due to permanent damage. One estimate of the disaster’s impact put the direct and indirect job loss at 7,500 and the payroll withdrawal at 32 million. Although deep mining still operated in Luzerne County until the early 1970’s mining employment plunged.

This event caused major changes in the mining laws of Pennsylvania today. According to section 302 in the Pennsylvania Anthracite Coal act, just one of 1,405 sections; Maps of all mines should accurately show the boundary lines of the lands of the said coal mine or colliery and the proximity of the workings thereto, all pipelines, streams or other bodies of water, buildings and structures, roads and highways and in case any mine contains any water dammed up in any part thereof, it shall be the duty of the operator or superintendent to cause the true location of the said dam to be accurately marked on said map or plan, together with the tidal elevation, inclination of strata and area of said workings containing water, and whenever any workings or excavations are approaching the workings where such dam or water is contained or situated, the operator, superintendent, or mine foreman, shall notify the inspector of the same without delay. If this law existed and was enforced at an earlier time it could have eliminated many of the factors which led to the disaster such as mining so close to a body of water in the first place.

There are two memorials along the Susquehanna River located on the newly renovated trails. One of the memorials is located outside of the River Slope entrance and the other outside of the Eagle Shaft where the majority of the men escaped. Recently, at the annual river festival the citizens of the local community commemorated the 50th anniversary which honored those 12 men who died and the brave survivors of that cold tragic day in 1959.

In the end this unpleasant incident revealed the fraudulent activity of the Northeastern coal industry and the repercussion was the reformation of the coal industry as Pennsylvania knows it today. Although it took the lives of twelve innocent men to raise this awareness, they will be missed by their friends and families and always be remembered as heroes.

Sources:

- “Deepminesafety: Mining Laws.” PA Department of Environmental Protection. 11 Nov. 2009.

- “Heritage: Knox mine by Robert Wolensky.” PA Department of Environmental Protection. 15 Oct. 2009. <http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/knox_mine/18688....

- John Williams Testimony, Joint Legislative Committee to investigate the Knox Mine disaster, March 19, 1995, 893.

- Rynkiewicz, Rose D. “Remembering the Knox Mine Disaster.” Personal interview. 3 Sept. 2009.

- Wolensky, Robert C., Kenneth C, Wolensky, and Nicole H. Wolensky. Voices of the Knox Mine Disaster. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission, 1999.