Barnes Foundation Archives

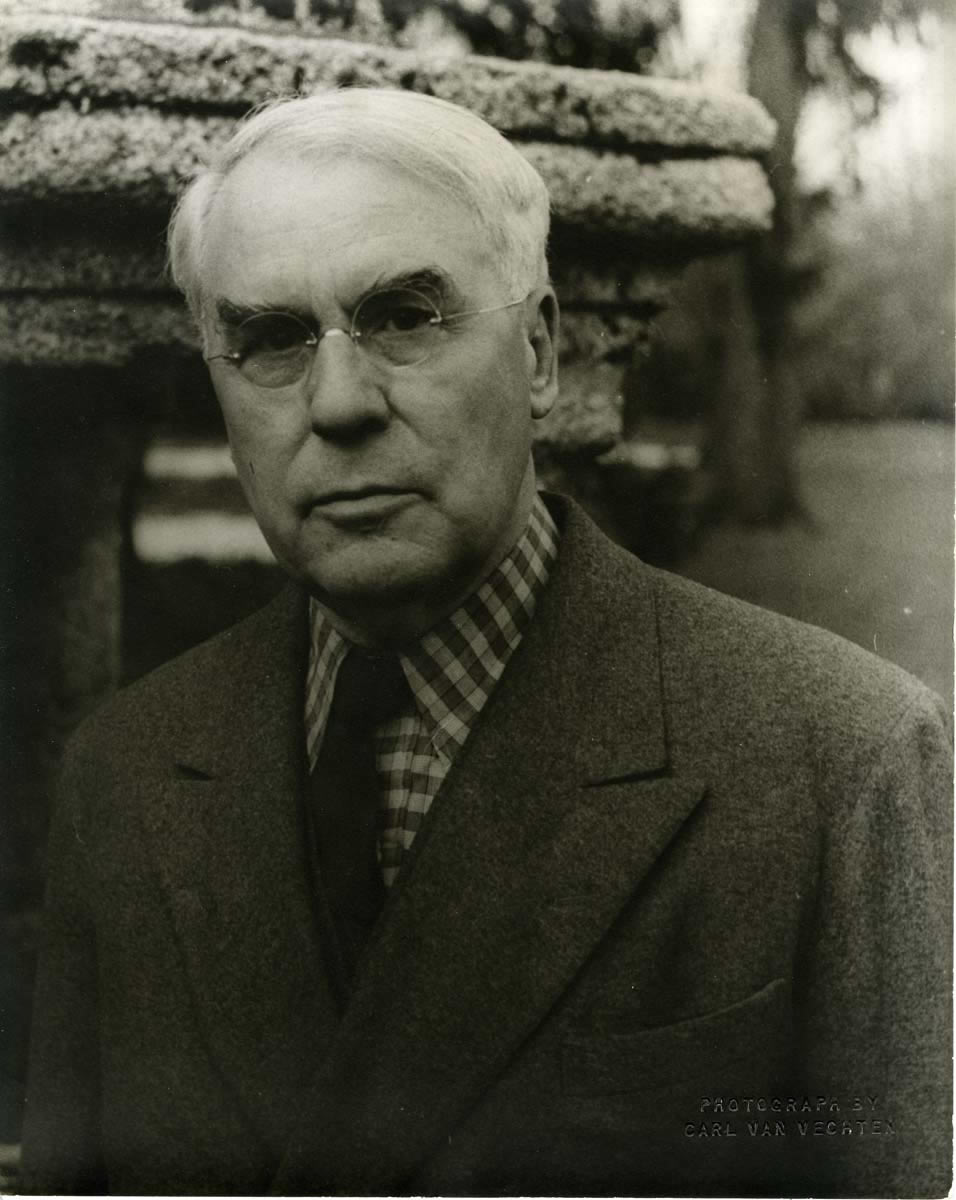

On the fourth of December, 1922, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania granted a charter to a new, unique educational institution—The Barnes Foundation. Despite later being hailed as “one of the most striking things in America” by the artist Henri Matisse, and as, “the most beautiful homage, rendered in America, to French art” by Waldemar George, a critic on Polish and French art, the Barnes Foundation did not elude criticism or debate. The unconventional display of art was the subject of much controversy, as was the founder, Albert C. Barnes, who challenged both the presentation and study of art by other academics and intellectuals.

Born January 2, 1872, Barnes grew up in the working-class community of Kensington, Philadelphia. In The Devil and Dr. Barnes: Portrait of an American Art Collector, Howard Greenfeld portrays Barnes’ childhood as a difficult one, one in which his family was no stranger to poverty or hunger. Barnes became interested in art as a young boy, and one of the most important early experiences for Barnes growing up resulted from his family’s devout Methodist practices. In his youth, he would attend African American revival meetings with his parents. These meetings opened his eyes to that culture’s different forms of creative expression—especially the unique paintings and sculptures, as Carol Soltis puts it. Sensing her son’s potential, Lydia Barnes encouraged him to pursue an education, and he was accepted to and graduated from Philadelphia’s Central High School and later from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School.

Dr. Barnes was an extremely intelligent and ambitious young man. His mastery of chemistry helped him in his jobs as a clinical medical doctor at the University of Berlin, as an advertising and sales manager for H.K. Mulford and Company, Philadelphia’s leading pharmaceutical manufacturer, and in his studies at the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität in Heidelberg, Germany. During his time at Mulford, Barnes came into contact with Hermann Hille, a German chemist with whom he later started a company producing a new type of antiseptic, Argyrol. Barnes and Hille later found themselves in an ongoing argument followed by a lawsuit, in which Barnes gained control of the entire company.

Barnes Foundation Archives

The history of Barnes is in a sense a rags to riches story—born into poverty, Barnes possessed the will, determination, and intelligence that led to his control of the A.C. Barnes Company and the millions of dollars that came with it. With newfound financial security, Barnes needed a new goal to pursue, and he returned to his childhood interest in art. The limited knowledge he had regarding quality art was reflected in his initial small collection that he showed to a childhood friend and artist, William Glackens. Barnes took his friend’s criticism because it was genuine, and his interest in modern European artists was born. Glackens was later convinced by Barnes to travel to Europe in 1912 to help expand his collection, authorized by the millionaire to spend up to $20,000 on work he felt was the best according to Greenfeld. Although Barnes was initially disappointed with the works obtained, by totally immersing himself in the study of various artists and genres, Barnes quickly developed his own way of analyzing and understanding different forms of art, and learned to appreciate the works he received.

Soltis writes that Barnes “focused on art's universal elements of line, light, color, and space and their relationships, and he explained that these elements created art when their unique combination became richly expressive of common human experience or values.” He worked tirelessly to expand his collection, making frequent trips to Europe and buying anything and everything that caught his eye.

By the 1920s, Barnes’ collection had become too large to be properly displayed in his home, and he set out to find a gallery for his it. Along with his desire to display his collection properly, Barnes longed to share his views and interpretations on art with others. In 1922, Barnes purchased the twelve acre Wilson Arboretum, located in the town of Merion, Montgomery County. He assured the former owner, Captain Josephy Lapsley Wilson that he would preserve the arboretum’s landscape. In September of that year, Barnes applied for a charter from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for his new educational institute, which would “promote the advancement of education and the appreciation of the fine arts.”

Monet, Manet, Renoir, Matisse and Cézanne paintings have decorated the walls of the Barnes Foundation in Merion since its founding in 1922. The grand entryway into the building and the exquisite garden provided primarily students an amazing opportunity to study art and nature for the past several decades. Among the 800 paintings housed within the building are van Gogh’s “The Smoker” and Cézanne’s “Valley of the Arc.” There are an impressive 181 paintings by Pierre-Auguste Renoir and 59 by Henri Matisse. Other artists include Picasso, Rousseau, Degas, and Seurat. These paintings are the “Crown Jewels” of Dr. Barnes’s impressive collection. For several years there was a great deal of controversy over the stringent viewing policies enforced by the Foundation.

Barnes had assembled “the finest collection of modern paintings in America” according to Alfred H. Barr, Jr., who would later become director of the Museum of Modern Art. Art critics as well as the public wanted a chance to view the collection. Dr. Barnes had his own opinions on the matter. The Foundation was an educational institute not a museum, and therefore any public viewing would interfere with his students learning. Upon the grand opening of the Barnes Foundation, Leopold Stokowski, famous director of the Philadelphia Orchestra expressed his annoyance with Barnes citing his “stubborn insistence that he didn’t want people to visit Merion merely to enjoy the paintings, and that the Foundation’s aim was a far loftier educational one.”

As Barnes’s collection continued to expand over the years, so did the public’s desire to view his collection. Barnes’s temper did not improve. He often quarreled with academics, critics, and the press over any criticism of his collection or teaching doctrines, as well as other institutions with whom he tried to work but ultimately failed to live up to his expectations. Prior to 1960, the only way to view the collection was by obtaining a personal invitation from Dr. Barnes, or enrolling as a student. Howard Greenfeld suggests in The Devil and Dr. Barnes: Portrait of an American Art Collector that in general, the more uneducated an applicant, the more likely they were to gain access. This was due to Barnes’s belief that educated people had already had their views corrupted, and would be unable to learn his doctrine.

On July 24, 1951, Dr. Barnes was killed in an automobile accident at the age of 79. His Foundation’s viewing policy was taken to court in 1952, an attempt to open the Foundation to the public due to its tax-exempt status (barnesfoundation.org). The suit was dismissed, but on December 10, 1960, nine years after the death of Dr. Barnes, the Foundation he created reached an agreement with the Pennsylvania Attorney General to “open the gallery to the public two days each week.”

Recently the Barnes Foundation has announced that they will be moving to a location in Philadelphia in 2012 in order to bring more revenue and reach more visitors. The Friends of the Barnes Foundation, a “citizens group dedicated to educating the public about the unique legacy and mission of the Barnes Foundation,” have battled to prevent this from happening. They believe that the building is a national landmark and needs to be preserved in its original location.

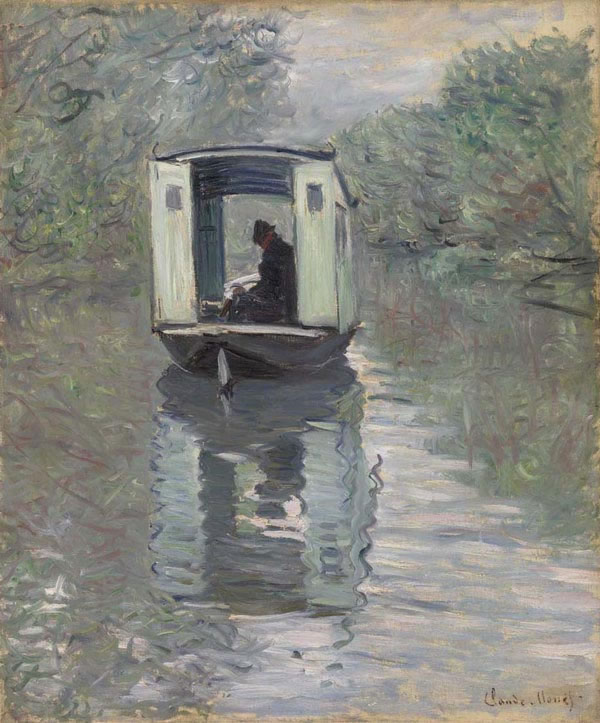

The Studio Boat (Le bateau-atelier), 1876

Oil on canvas, 28 5/8 x 23 5/8 in. (72.7 x 60 cm)

BF730, The Barnes Foundation, Merion, PA

On February 29 2007, artist and member of the Friends of the Barnes Foundation, Nancy Herman, wrote an op-ed piece in the Philadelphia Inquirer, entitled, “Keep the Barnes and Build Another.” In the article, Nancy suggests the construction of a separate museum that would hold only contemporary art. This would allow the original building to remain in place and a new one in Philadelphia to attract more visitors. In 2009, the documentary The Art of the Steal was released that chronicled the Friends of the Barnes Foundation’s struggle to keep the Foundation in its current location.

While the controversy surrounding the Barnes Foundation’s expansion from Merion to Philadelphia continues, it is important to recognize it is an expansion. The Cret building in Merion which housed Dr. Barnes art collection and was the site of educational classes will remain a part of the Foundation, and will become the primary site of the Foundation’s archives. The Barnes arboretum and herbarium which included over 200 species of plants at the time of its origin, a number which can still be found there today will also remain in the Foundation’s care.

The new location on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway will provide more space for the art and sculptures, more classrooms for the courses to be taught, and improved lighting in order to better see the artwork. The new design termed a “gallery in a garden” will contain outdoor gardens and an atrium that visitors would walk through in order to get into the museum. Dr. Bernard C. Watson, the Chairman of the Barnes Foundation Board of Trustees, stated that “the guiding principle in this project has been to respect the underlying educational mission of the Barnes Foundation, to replicate the galleries and ensembles as well as the garden setting, and to create additional opportunities for increased access.”

While The Barnes Foundation is scheduled to open its new building on Benjamin Franklin Parkway in 2011, the historic beginnings of the Foundation and its magnificent art collection and arboretum, will forever rest in Merion, Montgomery County.

The Center would like to thank the Barnes Foundation for its assistance in illustrating this article.

Sources:

- The Barnes Foundation. 2 Mar. 2011 <http://www.barnesfoundation.org>.

- “The Barnes Foundation Unveils Design by Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects for the New Building in the Heart of Philadelphia.” The Barnes Foundation. 7 Oct. 2009. 31 Mar. 2010 <http://www.barnesfoundation.org/about/press/media-info/pr-100709>.

- Greenfeld, Howard. The Devil and Dr. Barnes: Portrait of an American Art Collector. Philadelphia, PA: Camino, 2006.

- Herman, Nancy, “Keep the Barnes, and Build Another.” Editorial. The Philadelphia Inquirer 28 Feb. 2007 <http://articles.philly.com/2007-02-28/news/25237851_1_barnes-museum-barn....

- Kern, Steven, et. al. A Passion for Renoir. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996.

- Raymond, Jay. “The Barnes Foundation and Education.” Friends of the Barnes Foundation. 2006. 26 July 2008 <http://www.barnesfriends.org/downlload/com-BarnesFoundationEducationRaym....

- Soltis, Carol Eaton. “Barnes, Albert Coombs.” American National Biography Online. Feb. 2000. American Council of Learned Societies. 29 Mar. 2010 <http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-00049.html>.

- Wattenmaker, Richard J., et. al. Great French Paintings from The Barnes Foundation: From Cézanne to Matisse. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993.