When mass production of the automobile first began in the United States, traffic accidents and fatalities began popping up everywhere like daisies in the spring time. Not yet accustomed to the power of automobiles and the potential deadly results one would later expect through their misuse, the responsibility that came with operating them took time for Americans to develop. Norman Damon, former Vice President of the Automotive Safety Foundation, stated, “The first traffic fatality in the United States was recorded in New York City in September 1899… The millionth traffic death was recorded in December 1951.”

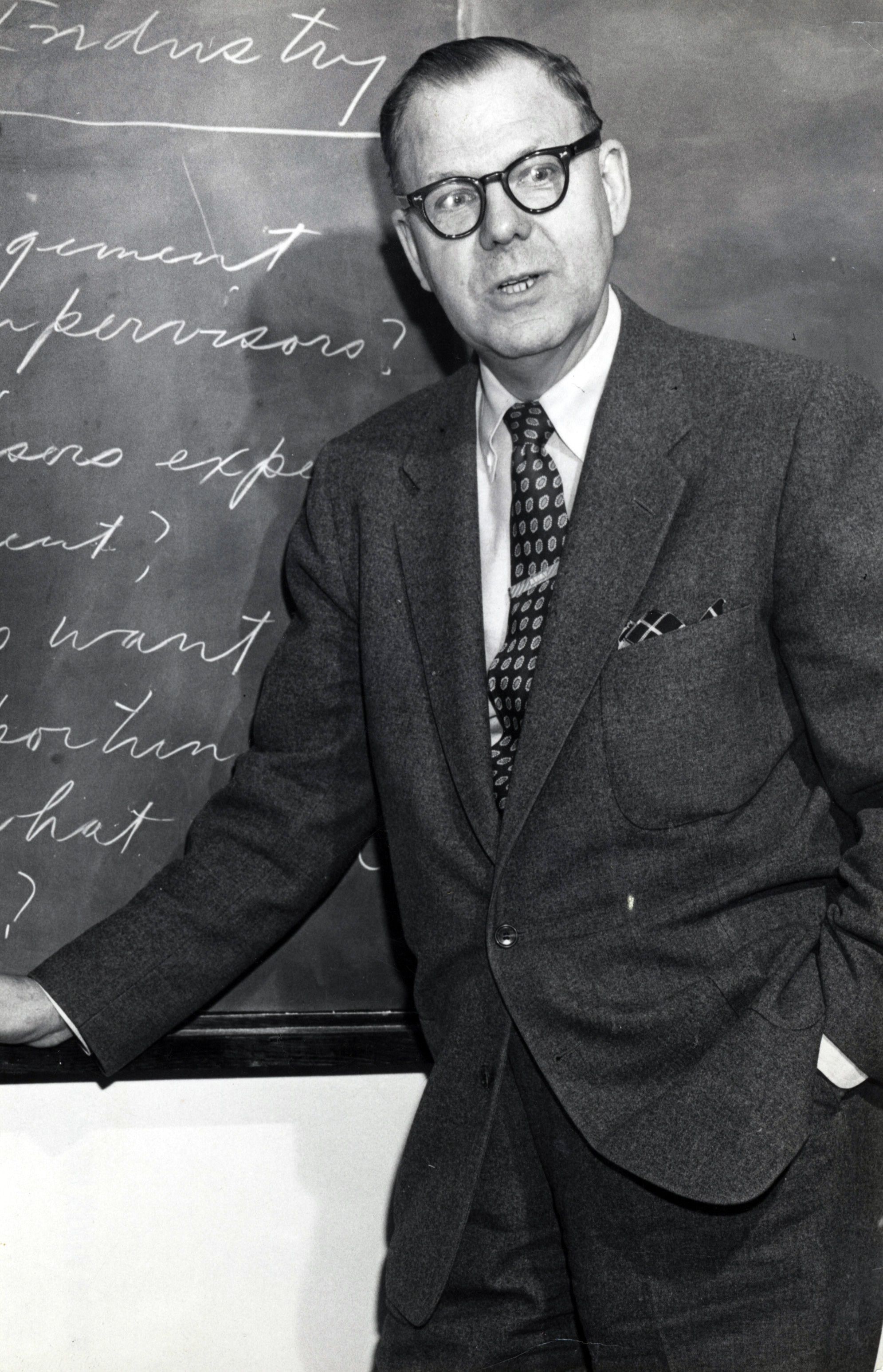

With the ever increasing number of traffic accidents, safety while driving an automobile needed to become a priority. Groups like the Highway Education Board and the Eno Foundation for Highway Traffic Regulation formed to promote highway safety in 1922 and “a general code of highway traffic regulation was adapted based on the continuation of work done by the Council of National Defense.” It was not until ten years later, in 1932, that the most obvious approach was undertaken to reduce traffic accidents – the development of a driver education course. Amos Neyhart, assistant professor at Penn State University initiated “the first organized high school driver education course [in the country] at State College High School, State College, Pennsylvania.”

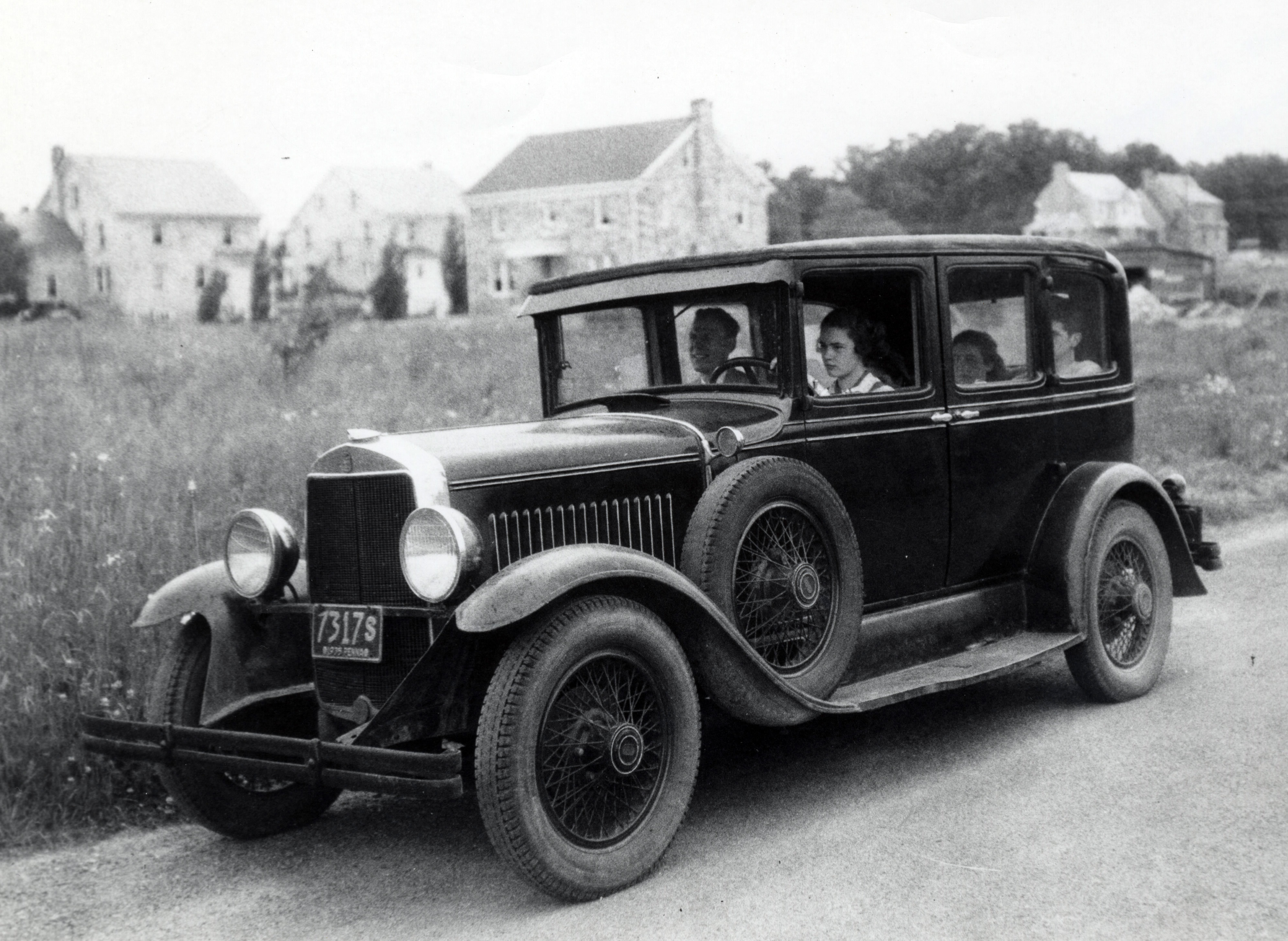

Neyhart decided it was time to begin teaching future drivers how to drive, and how to do it safely, after a drunk driver reportedly hit his parked car. In his mind, Neyhart believed that the frequency of traffic related accidents was largely due to the fact that “at the present time [1934], the effort put forth in teaching new drivers is very small.” He began teaching safe behind-the-wheel practices to students at State College Area High School in his own car, a 1929 Graham-Paige.

In 1934, after becoming an instructor for the classroom and in-car portions of the Driver’s Education course, Neyhart wrote a guide-book for instructors entitled, Instructors Guide Book – For Training Drivers For Emergency Driving, and submitted his thesis to the university, The Relation Of The Training And Other Characteristics Of Automobile Drivers To Their Proneness To Accidents. Neyhart’s first concern with implementing driver education courses in schools was determining whether or not instructors possessed the necessary qualifications needed to fulfill their job requirements.

In his Instructors Guide Book – For Training Drivers For Emergency Driving, Neyhart advises instructors to: volunteer for at least forty hours of training, be willing to use their own car and tires no less than five hours a week, be between the ages eighteen and fifty, have a valid driver’s license, have driven at least 3000 miles in the last three years, pass a diagnostic road test to show proficiency in handling a vehicle under varied driving conditions, and have good hearing and vision. “Such drivers,” Neyhart explains, “must know much more than the average driver about motor vehicles so that they can intelligently maintain their own automobile or motor corps equipment and even make certain emergency repairs on the road.”

These qualifications may seem excessive to modern day drivers, but Neyhart’s research supports his strict qualifications. Neyhart stresses the importance of teens developing the correct driving habits and skills. “Youth is eager and anxious to learn” Neyhart argues; “Both muscle and mind are pliable,” and thus there are several factors the instructor must consider in training young drivers. Does the length of the teacher’s driving experience have an appreciable effect on the accidents of the learner? What effect has the teacher’s style of driving on the learner’s driving habits? Has the personal relationship of the instructor and learner any effect on proneness to accidents? These are just three of thirty-two factors Neyhart desires instructors to consider while teaching students, and are why he suggests teachers be even-tempered, sympathetic, have unusual patience, and not be easily excited or angered.

Neyhart similarly suggests that students in driver’s education courses need to take the course seriously, and listen attentively to what the instructor has to say. In Neyhart’s additional text, Instruction Book on the Safe Operation of a Motor Vehicle For Teachers and Learners, he states “The learner should realize that every careless and inattentive act on his part, not only endangers his life, but the lives of his passengers, pedestrians, and occupants of other vehicles.”

Neyhart believed that the key to successfully implementing driver education in schools, and seeing an improvement in teen driving, would be placing the course early in the semester, prior to the students reaching the minimum driving age. It was additionally important that the course count for credit, and not be regarded as an extra-curricular activity or club. As he put it, “In the adult world driving a car is definitely not a hobby.”

The guidelines Neyhart established for driver’s education courses during his time have mostly survived and continue to be taught in classrooms today. With improvements to technology, some of the requirements Neyhart would have required for one to obtain a driver’s license have disappeared – for instance when Neyhart taught his in-class portion of the course, he emphasized the importance for his students to have a “general knowledge on how a car runs and how to keep it running properly.” While he acknowledged that it was not a course that was designed to make mechanics out of its students, knowing the parts of a car’s engine and how they worked was something he believed would contribute to his student’s safety on the highway.

With the constant improvements to technology today, Neyhart would surely be astounded by the invention of cars like the Lexus LS 460L, which parallel parks itself. In the 21st century there are still men and women who know a great deal about the inner workings of automobiles, but it isn’t information that is absolutely necessary for a driver to know. If one notices irregularities in the performance of one’s automobile, the simple solution is to take it to a repair shop. If Neyhart’s “general knowledge” was still widely taught today, drivers could probably save a significant amount of money performing manual repairs themselves. Neyhart standardized teaching guidelines for driving instruction and “sportsmanlike driving,” which range from what a driver should do before starting the engine, to brake time, how to properly shift gears, to driving on the open highway. These guidelines and many others are still used today, and can surely be said to have made an impact on the safe driving habits of millions of American drivers.

Sources:

- “Amos Neyhart; Father of Driver Education Classes.” Los Angeles Times 21 Jul. 1990:28.

- Damon, Norman. “The Action Program for Highway Safety.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 320.1 (1958): 15-26.

- Eno, William Phelps. “Street Traffic Legislation and Regulation in the United States of America.” Journal of Comparative Legislation and International Law 7.4 (1925): 238-247.

- Neyhart, Amos Earl, and Mary Helen Neyhart. AAA Instructor’s Guide Book for Training Drivers for Emergency Driving. Washington, DC: American Automobile Association, Traffic Engineering & Safety Dept., 1944.

- Neyhart, Amos Earl. Driver Education; the Key to Safe Operation of Motor Vehicles. Washington, DC: N.p., 1954.

- Neyhart, Amos E. The Driver. Washington, DC: American Automobile Association, 1936.

- Neyhart, Amos E. 1934. The Relation of the Training and Other Characteristics of Automobile Drivers to Their Proneness to Accidents. Masters Thesis, Pennsylvania State University, State College. 97 p.