On a typical work day hundreds of people on their way to Philadelphia ride the R5, the most heavily utilized commuter regional rail line within The Southeastern Pennsylvania Transit Authority (SEPTA). About thirty miles west of the city, SEPTA’s R5 passes through Malvern, a quaint town that seems no different than others along the renowned Main Line. But every town has its secrets.

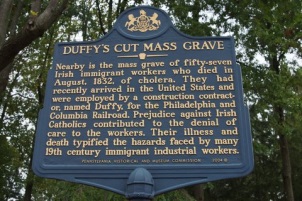

What most passengers aboard the R5 don’t realize is that seconds before the brakes bring the train to a screeching halt at Malvern station, they are passing over the site of a mysterious scandal. Just beyond the railroad station is Duffy’s Cut, the focal point of the tale of 57 Irish immigrants who left their deeply divided homeland in search of a better life in America, only to be discriminated against, struck with disease, and tossed into a mass grave beside the tracks within two and a half weeks of their arrival.

Their mass grave is believed to lie in the woods near the corner of Sugartown and King roads in Malvern, Chester County. The tale of Duffy’s Cut is more than a local story; it’s even more than an Irish story. It’s a story of human indifference and cruelty, of family legends, and of the power of technology to uncover the truth.

In April 1832, a ship called the John Stamp embarked on a journey from Derry, Ireland, to Philadelphia. Aboard the ship were about one hundred Irish immigrants. They left poverty and religious strife in Ireland; they came in search of “The American Dream.” After a long journey, the John Stamp arrived in Philadelphia safely on June 23, 1832, during an unusually hot and humid summer. Historian Earl Schandelmeier III sums up what it was like for an immigrant at this time, “you came over and either made your way or you didn’t.”

Coinciding with massive immigration was the industrial revolution. The third decade of the nineteenth century drastically changed the economic landscape of America. It was general consensus among political and business leaders that there was a need to expand west. Historian Dr. William Watson discusses the interstate competition and the immense pressure it put on Pennsylvania in the 1820s. New York State and Maryland had just constructed the Erie Canal and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad respectively, drawing traffic and business to them. Finally, in 1826, Pennsylvania passed a state legislation to create the Main Line of Public Works, a canal and railroad system connecting Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. As Watson proclaims, “this was one of the greatest industrial projects of the modern age.” The Main Line was broken down into four parts, the first of which was the Philadelphia to Columbia stretch, an eighty two-mile railroad connecting the Schuylkill River with the Susquehanna River and traveling through Montgomery, Chester, Delaware, and Lancaster counties.

In charge of a particularly difficult portion of this stretch was Phillip Duffy, an Irish contractor who lived in Willistown Township, Chester County. He had many contracts with the Philadelphia & Columbia and West Chester Railroads from 1829 to 1849. Track Mile 59 of the former was significantly more difficult than any other mile and delayed the whole project for over a year. It was the hardest to build and went over budget by about $7,000. According to historian Schandelmeier, “the contract involved three steps: to fill the valley, create a culvert for the stream, and grub away the existing hillside.” Today, these tasks would be easily completed with construction equipment, but by hand it was extremely time consuming and dangerous. As Lancaster resident Dr. Matt Patterson states, “human beings were used like disposable parts.” Track mile 59, later known as Duffy’s Cut, was a setback. Duffy was in need of men who would work tirelessly for little pay.

Phillip Duffy ventured down to the Philadelphia docks on June 23, 1832, and met the immigrants who had just come ashore from the John Stamp. He greeted the immigrants and persuaded 57 of them to work for him on track mile 59 (Duffy’s Cut). The men were put up in a shantytown and given strict orders not to leave the camp. Duffy’s new laborers were loathed by locals; they were looked upon as less than human. As Watson mentions, “these men were not liked, these men were not wanted.” They were ignorant of American customs and norms. It is possible that Duffy exploited these men. What is sure is that within two and a half weeks all 57 were dead.

Phillip Duffy and the local farmers were not the only foes these immigrants faced. In 1832, a global cholera pandemic had just reached Philadelphia, peaking in August. This intestinal disease induced uncontrollable vomiting and diarrhea. The cause of and cure for cholera puzzled even the finest doctors at the Philadelphia College of Physicians, the nation’s leading medical training center at the time. A wide range of ineffective treatments, such as bleeding out, exemplified how little was known about the disease. Even the Philadelphia Board of Health made inaccurate declarations about which goods were predisposed to cholera, such as liquor. Also, the prisons emptied nonviolent criminals who were healthy. There was turmoil in Philadelphia.

Belief that the Irish brought cholera to Philadelphia was becoming widespread. It didn’t matter in the public imagination that the Lazaretto, a quarantine station for incoming ships, had been established in 1799 for immigrants just outside the port of Philadelphia. The epidemic eventually reached the shantytown in Duffy’s Cut by August 1832. Scared and disgusted, a few of the men immediately tried to flee to local homes for assistance but to no avail. Watson speculates that the immigrants were forcefully quarantined in the shantytown because of prejudice and an attempt to prevent cholera from spreading. None of the workers left Duffy’s Cut ever again.

Nearly one hundred and eighty years later in September 2000, Watson sat in his office with a friend Tom Connor. Watson is a history professor at Immaculata University on King Road in Malvern. Conner directed his attention to bright lights at the faculty center, a venue that hosts university events from time to time. As reported by Watson, these lights were “shimmery like neon, in the figure of three thin men.” The two admired the flickering lights for a moment, and in that instant, the lights were gone.

Photo credit: Annemarie McGinley Patton

Immadculata University in Malvern, Chester County, is where Dr. William Watson heads the History Department and is also where Dr. Watson and friend saw the mysterious "shimmery" figures.

Watson was certainly puzzled by what he saw, but as time went on the memory began to fade. Two years after the eerie encounter, Watson went to his brother Frank’s house in New Jersey. Rev. Frank Watson is also a historian and Lutheran minister. When the two brothers met, they frequently reflected on their late grandfather, Joseph F. Tripician. As they were growing up, he told them many stories about the ghosts of Duffy’s Cut. Like many Malvern locals, the brothers dismissed these tales as folklore, yet they cherished his stories. Unlike most ghost stories, the Watsons’ tales had a degree of authenticity.

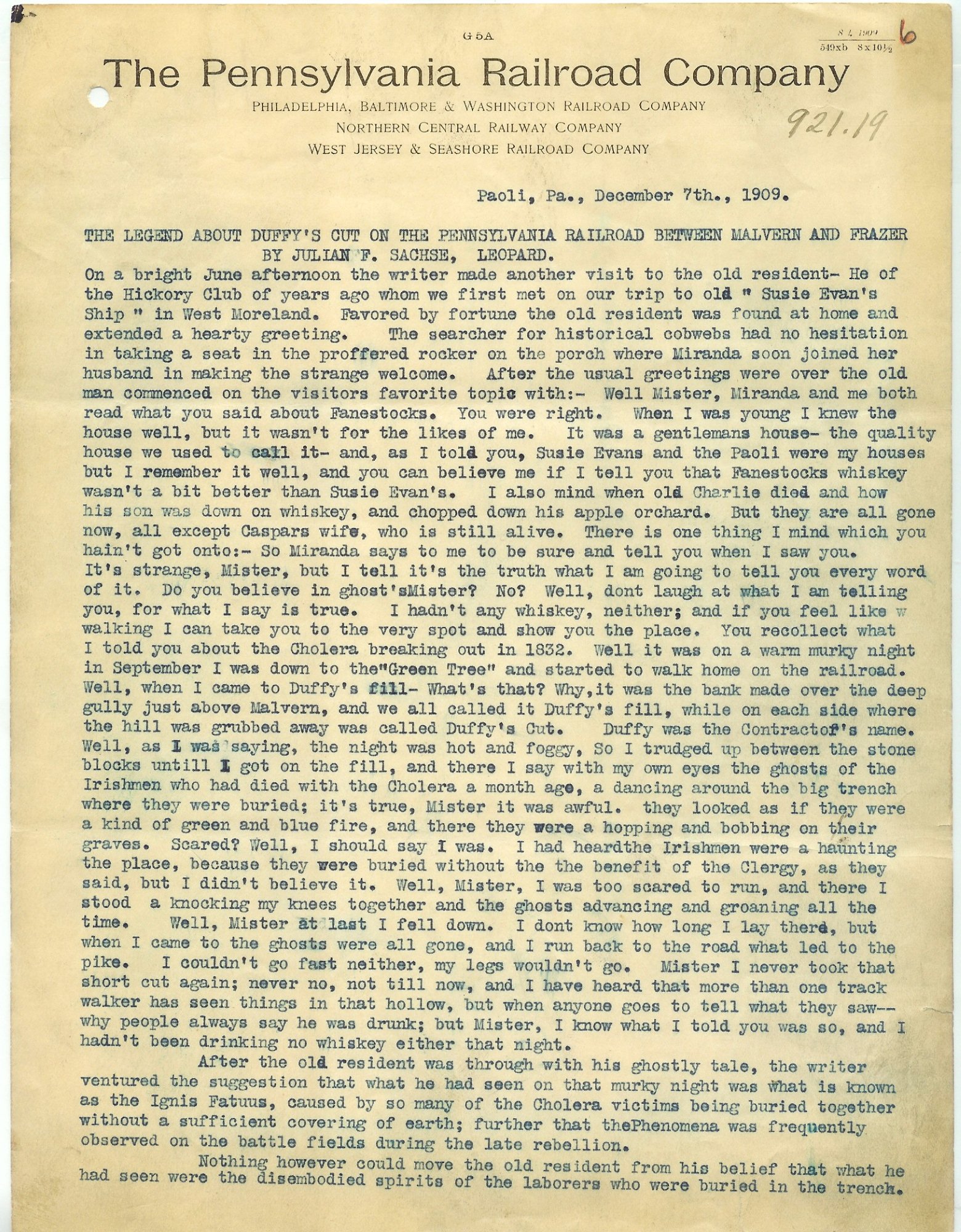

Tripician had been a secretary to Martin Clement, the 11th president of The Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), part of which would eventually become SEPTA. According to William Watson, in 1909, while in Paoli, Clement learned the story and began delve into what really happened, assembling a file with conclusive evidence along the way. The file included two statements by PRR employee Julian Sachse that were transcribed on PRR stationery by the Watson’s grandfather, and correspondence between PRR employees. Clement was so adamant about commemorating these men that he constructed a stone wall before the file was even complete.

The wall still stands today. He also intended on hanging a metal plaque that briefly described the details, but according to Clement, he was “turned down by the Division Engineer.” Clement held the file until his death in 1966. Frank Watson continues, saying that the file was given to Clement’s assistant, Watson’s grandfather in 1968. Upon Grandfather Tripician’s passing, the file was given to Frank by his grandmother in 1977.

The Watson brothers began to read the secret file, considering their grandfather’s old ghost tales in a different light. According to the Sachse document, “I saw with my own eyes the ghosts of the Irishmen who died of cholera a month ago; dancing around the big trench where they were buried…they looked as if they were a kind of green and blue fire.” The mention of a “big trench” was alarming, not to mention a description identical to what William Watson saw on that September night two years earlier. He called his friend instantly. “I know what we saw [Conner],” Watson insisted. There was no time to waste. The Watson brothers assembled a team of historians and volunteers, and began their research frantically. According to Frank Watson, they were plowing through state and local archives “like a mob scene.”

Photo credit: Rev. Frank Watson

This is a scanned page from the Sachse documents that were concealed for over a century and eventually handed down to the Watson brothers from their grandfather.

As the team researched, a scandal slowly emerged through discrepancies among the details of the story. Varying accounts of the virulence of the cholera epidemic increased skepticism among the team. For example, on September 8, 1832, Philadelphia’s National Gazette and Literary Register published a piece called “Cholera Intelligence.” Their coverage of cholera in Duffy’s Cut read as follows: “It is reported that several cases have occurred lower down the [Great] Valley, among the labourers on the Pennsylvania Railroad.” On the worst day in the Philadelphia cholera epidemic, August 7, there were 176 cases with 71 deaths. A 100% percent mortality rate for “several cases” was unlikely, but a 100% mortality rate for 57 cases was impossible. The team had all the research they needed. It was time to dig.

To investigate further, the Watsons recruited specialists. The newest additions included: geophysicist Timothy Bechtel of the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn); Chester County Deputy Coroner Norm Goodman; Janet Monge, the Keeper of Skeletal Collections at the UPenn Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology; and Dr. Matt Patterson, a forensic dentist. After two years of research, the team began to dig on a hot morning in August 2004.

Many locals wrote off the brothers’ efforts. William Watson recalls, “people told us we were chasing ghosts; we would never find the bodies.” Bechtel’s geological surveys and sonar technology were advantageous, but the excavating itself would still be guesswork.

In November 2005, the team found evidence: the bowl of a clay pipe. According to University of Maryland professor of Archeology, Stephen Brighton, this clay pipe is “the oldest example of Irish nationalism found in North America.” The team’s latest discovery assured them that they were on the right path. Though hopeful, Bechtel pointed out, “there’s a lot of territory out there.”

Photo credit: Annemarie McGinley Patton

In March 2009, after five tireless years of seemingly unproductive digging, the team finally found what they had been searching for. Amongst a grove of trees just behind a housing development near the R5, they discovered a tibia, skull fragments, and more than eighty other human bones. After 200 years the team expected to see decomposition, but they discovered more than that. This skull had blunt force trauma.

All of the remains discovered were catalogued by archaeological experts and sent to UPenn. Bechtel compared it to a “monstrous jigsaw puzzle.” Over the next two years the team unearthed six more sets of skeletal remains. They also found evidence of a seventh under a poplar tree, but delayed excavation to ensure the remains were preserved.

The tulip poplar tree delayed excavation of the seventh body until July 2011. After the tree was felled, the team discovered that the bone had actually fused with the tree roots; the tree had fed off of the human remains over the years. Overall, the wait was worth it because excavation was done without damaging the remains.

At UPenn, Dr. Monge was able to determine signs of blunt force head trauma in three more of the seven sets of bones. The team speculates that some of the immigrants escaped the quarantine and were slaughtered, only to have their bodies returned to the shantytown in nailed coffins to avoid a riot among remaining immigrants. According to Dr. William Watson, it is well documented that a local vigilante group named the East Whiteland Horse Company existed in the area. He continues: “It is likely the rest were victims of vigilantes driven by anti-Irish prejudice, class warfare or intense fear of the dreaded disease.”

In February 2011, forensic dentist Patterson began testing one of the sets in which he found a strange dental anomaly. It was a defect in the upper right molar that occurs in 1 in 100,000 people, a feature that he referred to as “exceptionally rare.” Through this anomaly, DNA blood samples from residents in Ireland, and the John Stamp’s ship manifest, he was able to identify the remains. The skeleton was that of 18-year-old John Ruddy. At this point, the story began to draw global attention.

Six of the bodies were ceremoniously laid to rest at West Laurel Cemetery, Bala Cynwyd, in March 2012. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, there were over 500 people in attendance. Amongst the crowd was Kevin Conmy, Deputy Chief of Mission at the Irish Embassy in Washington. Conmy stated that the burial was important “for the millions of Irish people who have made this leap over the centuries.” In March 2013, Mr. Ruddy was given a ceremonial burial at the Church of the Holy Family in Ardara, Co. Donegal, Ireland. Finally seven of the immigrants from the John Stamp were put to rest. But the search for the other 50 goes on.

Currently, the team speculates that the mass grave is located in a spot dangerously close to the railroad tracks on Amtrak property. They await executive approval to begin the dig. If granted, an Irish contractor named Joe Devoy will do the excavating and Janet Monge will analyze the samples. As historian Schandelmeier wryly states, “it is ironic that an Irish contractor will be digging up bodies buried by an Irish contractor.” Although there may be skeptics, the team remains persistent.

Historian Dennis Downey says, “the team’s research offers insight into 19th-century U.S. attitudes towards immigrants, industrial work, disease, and culture.” The tale of Duffy’s Cut is sadly similar to that of the average 19th-century Irish immigrant and continues to be uncovered. As historian and late team member John Ahtes once reflected, “throughout history, human lives have different values, at different places, at different times.”

Sources:

- Barry, Dan. “With Shovels and Science, A Grim Story Can Be Told.” The New York Times 31 Mar. 2013: A-6.

- Callahan, Jim. “A cut above Duffy’s - Research into fate of Irish rail workers requires an aerial approach to a grave.” Daily Local News 17 Jul. 2011: A4.

- Callahan, Jim. “Beer and brew to raise funds for Duffy’s Cut. Organizers want to place memorial near 1832 mass grave for immigrants.” Daily Local News 14 Feb. 2011: 3.

- “Cholera Intelligence.” National Gazette and Literary Register 8 Sept. 1832: 1.

- “The Cholera.” Village Record.

- Holmes, Kristin E. “Long-forgotten dead of Duffy’s Cut get proper rites.” Philadelphia Inquirer 10 Mar. 2012: A01.

- Kanaley, Reid. “The R5: Commuter lifeline defines Main Line.” The Philadelphia Inquirer 15 June 2005: G09.

- “The Passengers on board the British Barge John Stamp.” April. 1832. Document from the collection of Dr. William Watson.

- Rutter, Jon. “Local Dentist, Using Skeletal Remains, Dental X-Rays, Helping To Give Some Belated Respect To 19Th Century Railroad Worker - Trying To Unravel Duffy’s Cut Mystery.” Intelligencer Journal 2 Mar. 2013: B1.

- Sachse, Julian F. “The Legend About Duffy’s Cut On The Pennsylvania Railroad Between Malvern And Frazer.” 7 Dec. 1909. Document from the collection of Dr. William Watson.

- Watson, Frank. Personal Interview. 21 February 2014.

- Watson, William. Personal Interview. 21 February 2014.

- Watson, William, Frank Watson, Earl Schandelmeier, and John Ahtes. The Ghosts of Duffy’s Cut. Westport CT: Praeger Publishers, 2006.