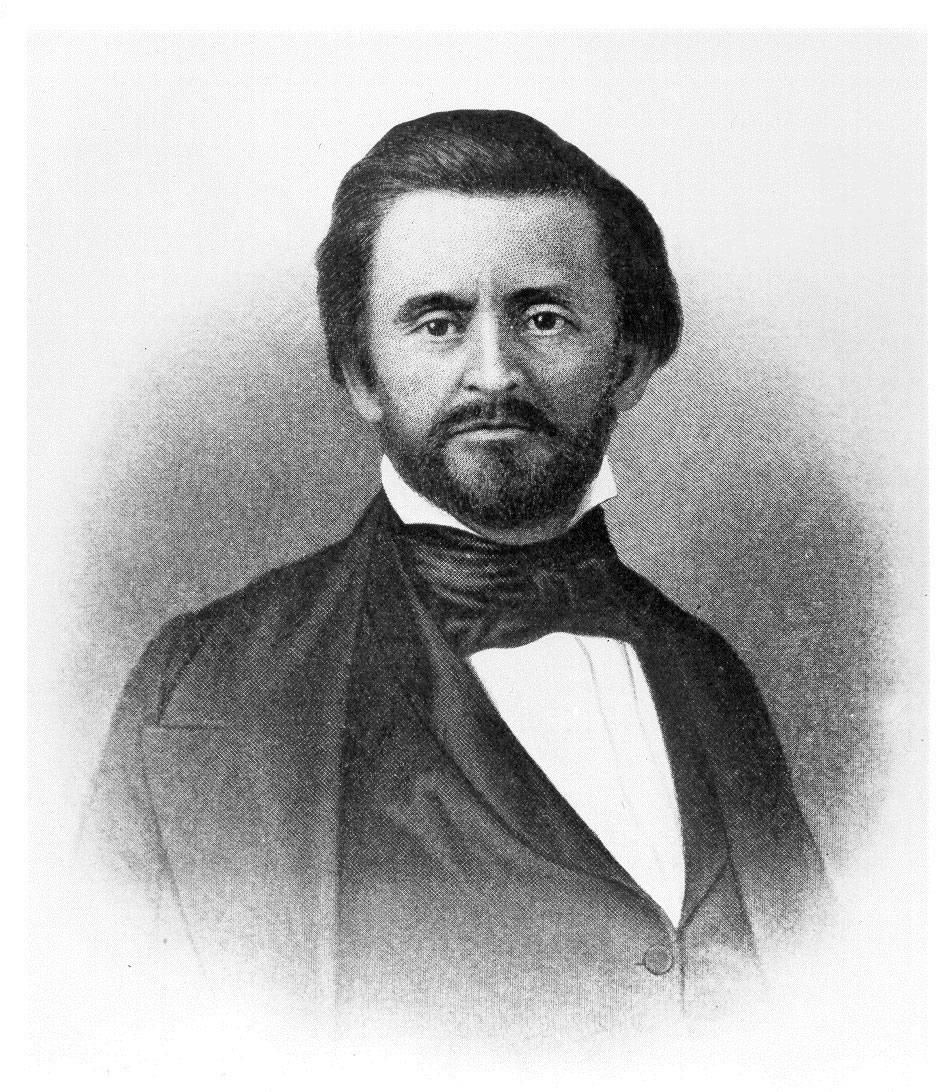

He never knew Fear… He spent much time, labor, and money opening and improving roads, constructing bridges, and helping every work which tended to develop the wealth of the new region (Warren, PA) about him.” These are the words used to describe Henry R. Rouse after his tragic death. He tried to drill to riches in Pennsylvania. His hunt for black gold led to an oil strike, the first oil well fire, and his untimely demise.

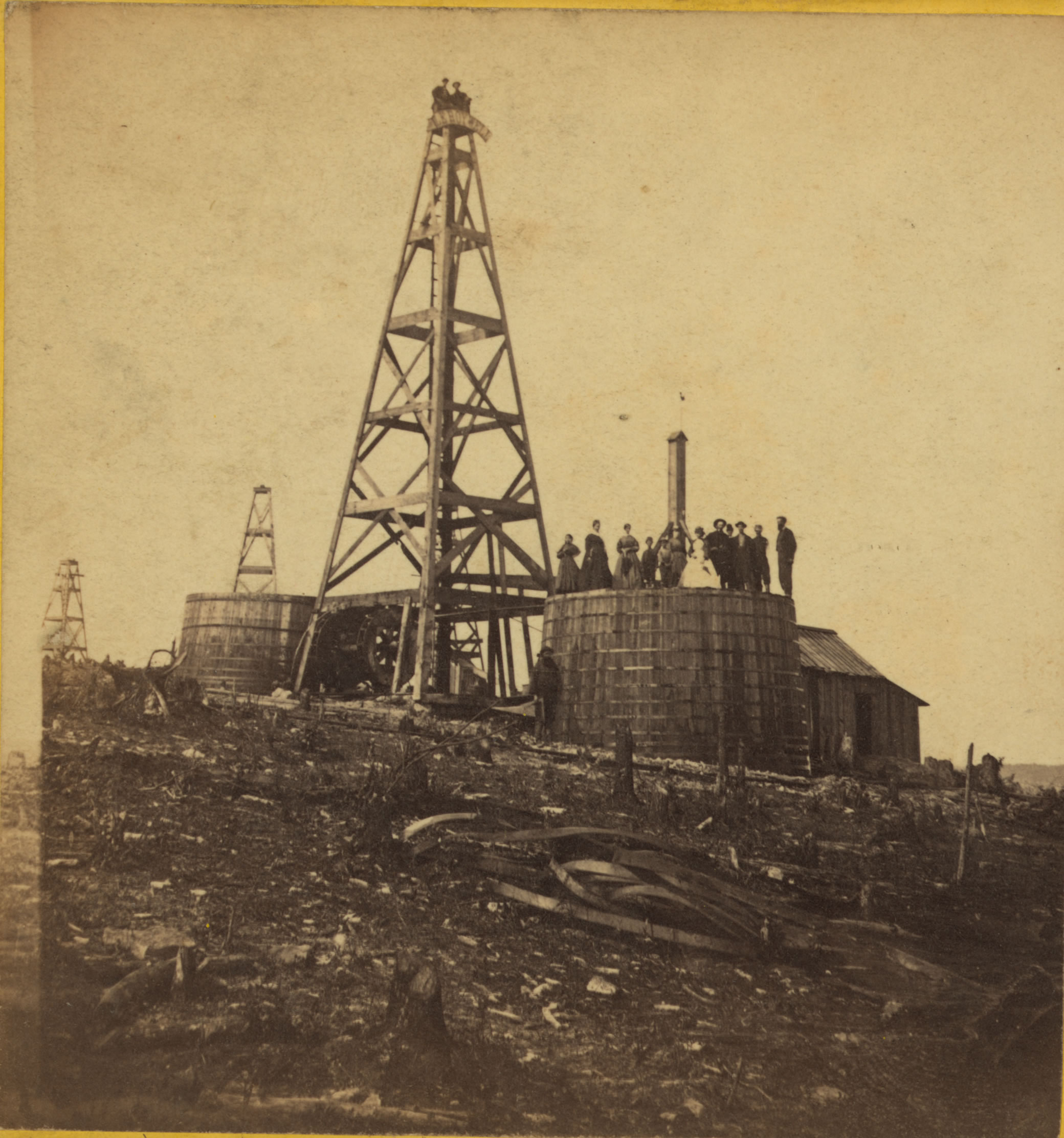

Black gold, as the old song says, runs rich in the history of Pennsylvania. The Drake Well, in Cherrytree Township, Venango County, was the first well drilled with the intention of finding oil, and certainly was not the last in Pennsylvania. After the Drake well’s success, many boom towns arose: Oil City, Titusville, Petroleum Center, Pithole, and Rynd Farm. These boom towns were along Oil Creek, a strip of land containing many reservoirs in the northwestern part of Pennsylvania along the Allegheny River.

The success and allure of Oil Creek came from the very shallow oil reservoirs in this area; anywhere from 50 to about 800 ft. The pioneering Drake well was only drilled to a depth of roughly 69 ft. This is very shallow compared to modern oil reservoirs. In comparison, the Marcellus gas shale wells in Pennsylvania is drilled to about 5,000 ft while wells offshore in the Gulf of Mexico are drilled to about an average depth of 15,000 ft. With the growing need for oil and the benefit of easy access, it is easy to see why so many boom towns sprang up in areas where the oil was so close to the surface.

However, with all the success came accidents and tragedies. The oil industry, like any other industry, is not perfect. The early years of drilling and production saw a number of problems. With oil reserves at such shallow depths, the easiest part was to drill the well. Once the oil had been reached, however, the first oil wells did not have the proper equipment and knowledge to deal with the ensuing gushing of oil. There were no pipe systems to move the oil and gas to storage systems away from the well. The well couldn’t be controlled and the oil would gush at its own rate. The very first disaster in the industrialized production of oil occurred in Pennsylvania’s own oil patch, in Venango County, in 1861.

To understand how the fire was started, it is first important to understand the oil reservoirs of Oil Creek. These reservoirs were conventional reservoirs. A conventional gas reservoir is when oil, natural gas, and sometimes water occupy the small air pockets in rocks. The oil, natural gas and water flow upwards until they reach an impermeable rock layer, a “barrier,” which traps the fluids creating a reservoir. Once the fluids have reached the barrier, they settle in order of their respective densities: natural gas, oil and then water.

When a reservoir was finally reached, the drill first came in contact with the highly pressurized natural gas. Daniel Yergin describes it as: “lightest gas fills the pores of the reservoir rock as a “gas cap” above the oil. When a drill bit penetrates the reservoir, the lower pressure inside the bit allows the oil fluid to flow into the well bore and then to the surface as a flowing well. ‘Gushers’ – ‘oil fountains.’” This event is described as a blowout.

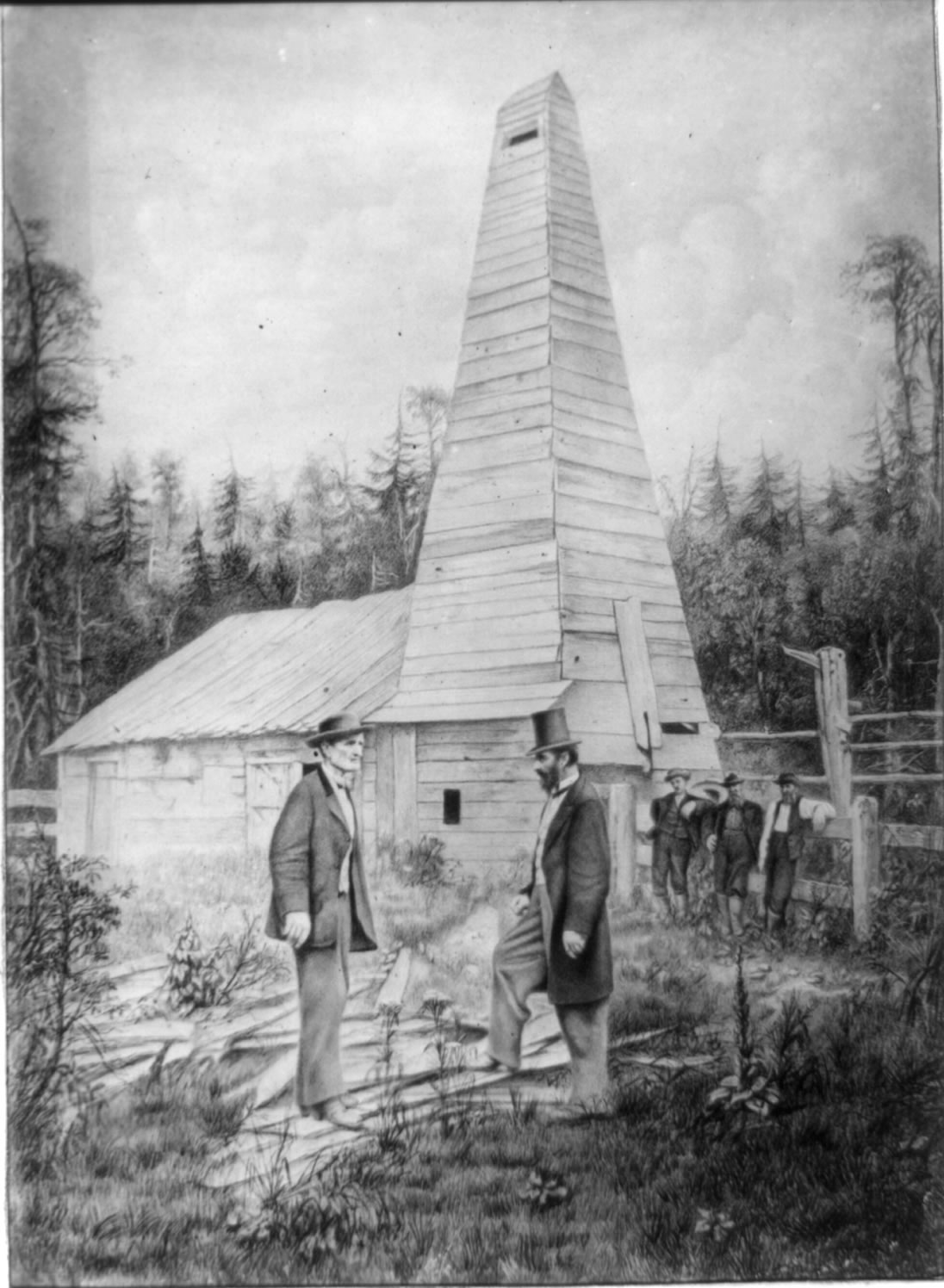

This lack of well control in early times led to what is generally accepted as the first oil well fire. The well was Little and Merrick Well on the Buchanan Farm on Oil Creek in Cornplanter Township, Venango County. On April 17, 1861, the crew drilling the Little and Merrick Well struck an oil vein with a gas cap.

The Little and Merrick well was Henry R Rouse’s second attempt to find oil in the “Creek.” His first well, the Barnsdall, was drilled with friend William Barnsdall. That well was only able to produce five barrels a day, a very small amount. Determined to make it in the oil industry, Rouse talked to farmers Archie and James Buchanan, who had a farm on Oil Creek, about leasing property from them to drill. After the first well on the farm was a bust, Rouse subleased the land to the Little and Merrick partners.

On April 17, the well was drilled to a depth of about 320 feet when an oil pocket was struck. News traveled fast, and most of the town, including Henry Rouse, was present, except George Dimmock. Dimmock ran in the opposite direction in hopes of finding barrels or tanks to hold the oil.

According to Dimmock’s account, the well was flowing at the rate of three thousand barrels per day. Many of the individuals in awe of the well became covered in oil. According to the April 1861 Clearfield Republican, at 6 p.m. the well ignited in flames. The cause of the fire is still debated. Some claim that the fire was ignited by a cigar in Rouse’s mouth. Based on the account of Dimmock, however, Rouse was very careful in making sure that cigars and pipes were not in close vicinity of the well. Another theory holds the fire was caused by a boiler about “8 to 10 rods” away (44 to 55 feet) at another well. The entire derrick was engulfed in flames. The well continued to produce as a 6 inch diameter of oil flowed into the air at a rate that did not subside. The oil continued to add to the fire as flames shot 30 to 40 feet in the air.

As the oil had covered the people who had been watching the well, so did the flames. A gruesome sight that Dimmock bore witness to: “Above the well and against the foot of the hill had been rolled two long tiers of barrels. One of the victims it would seem had been standing on theses barrels near the well when the explosion occurred; for I first discovered him running over them away from the well. He had hardly reached the outer edge of the field of fire, when coming to a vacant space in the tier of barrels from which two or three had been taken, he fell into the vacancy, and there uttering heart-rending shrieks, burned to death with scarcely a dozen feet of impassable heated air between him and his friends.”

Dimmock also saw Henry Rouse as he became engulfed in flames: “Mr. Rouse [was] standing probably within twenty feet of the well and among the very nearest of the spectators did not lose possession of his mind for an instant. He remembered the ravine, and dashed toward it. In the breast pocket of his coat was a book containing valuable papers, and in the pocket of his pantaloons a wallet containing a large sum of money. These he jerked from their places and threw them far outside of the fire where they were afterwards found in safety. He had accomplished but half a dozen steps when he stumbled and fell, still being within the circuit of the fire. He buried his face in the mud to prevent inhalation of the flames; then recovering himself bounded up the ravine, falling for a second time completely exhausted at a point where two men barely endured the heat long enough to seize and drag him forth.”

Rouse was dragged from the fire and flames by two men. Burned severely, and expecting the worst, Henry Rouse dictated his will to the men surrounding him as they fed him water spoonful by spoonful. Unable to write his own mark, the men who fed him water gently rolled him over so he could give his mark of approval. In his will Rouse was a very generous man, leaving much to others and providing for the poor of nearby Warren County, Pennsylvania.

Rouse truly “never knew fear.” As he lay on the ground in incredible pain, Rouse turned to a physician and stated “I will to know my exact condition.” Slowly the doctor came to Henry’s side and quietly said “Henry, you will have to die and that soon.” Upon this statement, a pastor emerged and offered religious comfort to the almost unconscious Rouse. Instead of asking for forgiveness or prayer, with his final breaths Rouse declared “My account is already made up. If I am a debtor, it would be cowardly to ask for credits now.”

Rouse closed his eyes for the last time, but the problems did not stop. The fire continued to burn the surrounding area. The nearby wells of Dobbs, Mason, Wadsworth, and Maxwell-Rice burned in addition to the Little and Merrick. The fire engulfed the entire Buchanan farm. As the fire raged, workers began digging ditches to move the excess oil from the other wells out of the reach of the fire. Once the oil had been moved to a safe distance, all attention was placed on the actual fire. It was finally extinguished after 70 hours by smothering the fire with dirt and manure. In all, some 19 people were killed in these 70 hours. An estimated two to four thousand barrels of oil were destroyed.

Even after the fire, the Rouse legacy goes on. Rouse’s name lives on in the good works of the Rouse Estate Foundation. The Rouse Estate consists of a nursing home and children’s facilitates which continues to serve Warren County as Henry Rouse himself wished to have done. The Rouse Estate was purchased by the Warren County Commission with the funds bequeathed to them in Rouse’s will. Every year the Warren County Commissioners make a trip to Henry Rouse’s grave in Westfield, NY to decorate his grave, just before Memorial Day.

It would be ideal to say that this well fire was the first and last, but it was not. Blowouts, the cause of this fire, are still a major problem for the oil industry. However, from tragedies like this one, has come knowledge. But the quest for complete oil well safety is still a work in progress. Every year new technology is created to prevent fires. When the Little and Merrick well was drilled, the workers had no place to store the oil that came gushing out. Now, pipe systems move the oil to a safe distance away from the well. Technology has also helped to prevent the rush of oil out of the well. No longer does the oil shoot to the sky, and all open flames are kept far from the well. In 1901, the first Christmas Tree was invented by Al Hamills under the supervision of Captain Lucas, Galey and J.S. Cullinan. 1922 brought Harry Cameron’s invention of the BOP (Blow Out Preventer). The wellheads and Christmas trees help to control the flow into storage tanks.

The fire of Little and Merrick cause immediate devastation, 19 dead, but the knowledge gained from the well along with other accidents has help paved the way for new and safer ways to drill. These inventions and precautions have become very important and helpful, especially considering many Pennsylvanians are back on the rigs again, this time drilling for the Marcellus Shale natural gas.

The Center appreciates the Rouse Estate’s assistance in illustrating this story.

Sources:

- Bourgoyne Jr., Adam T. Applied Drilling Engineering. Richardson, TX: Society of Petroleum Engineers, 1986.

- “Celebrate the 2009 Sesquicentennial of Oil Heritage.” Rouse Estate. 21 Mar. 2010 <http://www.rouseestate.org/Content/AboutUs/History/HenryRouse.cfm>.

- “Celebrate the 2009 Sesquicentennial of Oil Heritage.” Warren County Historical Society. 14 Feb. 2010 <http://www.warrenhistory.org/oil%20heritage.htm>.

- “Clearfield Republican, 1861 Issues.” PA-ROOTS. 10 Feb. 2010 <http://www.pa-roots.com/index.php/clearfield-county/167-clearfield-repub....

- “Extreme Oil.” PBS. 12 Feb. 2010 <http://www.pbs.org/wnet/extremeoil/>.

- Gillespie, Robert H. “Rise of the Texas oil industry, Part 2 Spindletop changes-the world.” THE LEADING EDGE 1995: 116-117.

- Henry, J. T. The Early and Later History of Petroleum. Cambridge, MA: J.B. Rodgers Co., Printers, 1873.

- “Historical Marker- Henry R Rouse.” Explore PA History. Feb. 10, 2010<http://explorepahistory.com/hmarker.php?markerId=1-A-AD>..

- “Legendary Drill and Production Equipment.” Cameron Marketing. 1995. Web. 1 Apr 2010.

- McLaurin, John James. Sketches in Crude-Oil: Some Accidents and Incidents of the Petroleum Development in All Parts of the Globe. Cambridge, MA: The author, 1902.

- Yergin, Daniel. “History of Oil.” US Oil and Gas Corp. 20 Mar. 2010 <http://www.usoilandgas.net/learnaboutoil.htm>.