A train rolled into the train station at dusk on November 18, 1863, carrying an entourage of politicians and public figures from Washington, D.C. to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Four months after Union troops defeated the Confederates in one of the bloodiest battles of the American Civil War, Soldiers' National Cemetery was slated for its opening dedication just outside of the small Pennsylvania town. Local organizers and Union representatives planned music, prayer, and an oration by the Hon. Edward Everett, a former United States senator and Secretary of State, as well as a president of Harvard University.

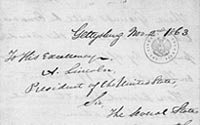

Almost as an afterthought, organizer David Wills, a prominent local banker, also invited President Abraham Lincoln to make "a few appropriate remarks." Wills made it clear that Lincoln needed to play only a small role. During the 19th century, federal participation was not necessary assumed or expected for state activities such as this. The states generally operated autonomously from Washington, and this instance was no exception. The Union states that had lost native sons in the Gettysburg campaign had funded and prepared the site without federal help.

Wills felt the need "for artful words to sweeten the poisoned air of Gettysburg." Five thousand horses and 8,000 people had perished in the early July fighting, and less than half of the bodies had been reinterred at the time of the cemetery commemoration. Some limbs still protruded out of their hasty coverings. Wills reasoned that a great speaker could perhaps lend the proceedings some much needed dignity. He first contacted the poets Longfellow, Whittier, and Bryan. Each turned down the offer.

Wills finally extended to Lincoln a casual invitation to make dedicatory remarks after Everett's oration. Although the speech was not supposed to be the highlight of the day's ceremonies, it became an enduring icon of American discourse and values. In 272 words and in less than three minutes, Lincoln would spark a new intellectual revolution.

On the afternoon of November 19, the town's population of 2,500 swelled to 20,000 as people gathered under clear, crisp skies for the commemoration. A spectacle of this magnitude was performance art for the contemporary folk. The audience completely surrounded a raised platform that seated the speakers, including Lincoln. After two bands played and a minister delivered a prayer, the featured speaker, Everett, took the stage. Everett, who had previously spoken at the battlefields of Lexington and Concord and Bunker Hill, had closely researched the Battle of Gettysburg. In two hours and 13,607 words, he chronicled the fighting. He blamed the Confederates for their atrocities while absolving Union General George Meade. The crowd clearly appreciated his attention to detail.

After a hymn, Lincoln unfolded from his seat for his remarks. He wore black attire with white gloves, as well as a mourning band for his recently deceased son on his trademark tall silk hat. Accounts of his exact words vary, even among the five versions he personally wrote. According to the version widely considered to be the standard — the "Bliss" version, which is the only one that Lincoln signed or titled — he said the following:

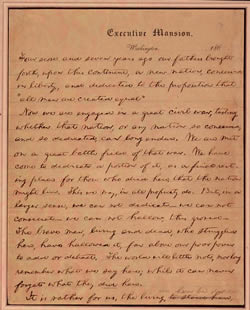

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation, so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

The length and content of the speech contrasted sharply with that of Everett, and the audience did not seem to know how to respond. Amid the muted reaction, Lincoln reportedly returned to his seat and told his bodyguard, "That speech won't scour. It is a flat failure." Some historians, however, dismiss that account as myth, citing the bodyguard's reputation for inaccuracies.

Regardless, the reactions were undeniably mixed. Some were stunned by the "inappropriate" brevity. Historian Garry Wills wrote that "myth tells of a poor photographer making leisurely arrangements to take Lincoln's picture, expecting him to be there for some time." Everett, however, was impressed, sending Lincoln a note the next day. "I should be glad," he wrote, "if I should flatter myself that I came as close in the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes."

Newspapers, which at the time generally catered to certain political audiences, portrayed the event in different lights. Some harped on the brevity. Others remarked on the elegance and heartfelt emotion of the carefully chosen words. The Chicago Tribune, for example, lauded Lincoln's address, saying, "The dedicatory remarks by President Lincoln will live among the annals of man." Cross-town rival the Chicago Times took another tack, saying, "The cheeks of every American must tingle with shame as he reads the silly, flat, and dishwatery utterances."

Both the criticisms and compliments revolved around the differences in style between Everett and Lincoln. Everett was a master of changing the tone of his voice to suit his needs. Lincoln, on the others hand, had a high, Kentucky accent that was quite unlike how his voice is portrayed in popular culture today. What he lacked in voice modulation, he made up for in carrying power and audibility. His delivery was emphatic, drawing interruptive applause five times.

The content of the rhetoric diverged as much as the speaking styles. "Everett succeeded with his audience by being thoroughly immersed in the details of the event he was celebrating," Wills writes. "Lincoln eschews all local emphasis. His speech hovers far above the carnage."

Lincoln never even mentioned slavery or sides. He went beyond the historical circumstances to a higher plane, evoking the ideals of equality promoted in the Declaration of Independence. Although Lincoln was not as outspoken for true racial equality as some of his contemporaries, he realized the necessity of guaranteeing basic levels of self-governance and self-possession. Equality, he reasoned, could not be denied if the United States were to live by its founding principles. Each newspaper's take on this reasoning certainly influenced how its coverage.

The publications also offered varying accounts of what exactly Lincoln said. Civil War historian Gabor Boritt compiled 30 pages of discrepancies for his book The Gettysburg Gospel. Most of the differences are small and understandable; some of them occurred because of reporters' impatience. The Centralia Sentinel, for example, recorded the "Four Score and seven years ago" introduction as simply "Ninety years ago."

Some newspapers inserted religious spin and additions. Although Lincoln had indeed grown more religious and the Gettysburg Address contained some Biblical allusions, he relied much more heavily on lawyerly speech, according to Garry Wills. The speech was more classical than it was religious. Still, certain papers took liberties with their transcriptions.

The five known Lincoln-written copies also contain differences, further contributing to the public debate over the wording on November 19. Each of these manuscripts is known by the name of the person who received the copy from the president. The first two went to two private secretaries, John Nicolay and John Hay, who traveled with Lincoln to southern Pennsylvania. These copies were written as thanks for their companionship and service, and they now reside in special sealed containers on display at the Library of Congress.

The other three copies were written considerably longer after the address. One went to Everett, the very man whose oration would forever live in Lincoln's shadow. The Everett copy is now at the Illinois State Historical Library. Another version, which is held at Cornell University, was presented to George Bancroft, a historian. The fifth Lincoln-made copy landed in the hands of Col. Alexander Bliss. For a time it was owned by a wealthy Cuban ambassador who had bought it at an auction in 1949 for a then-record price of $54,000. Before his death in 1957, the ambassador willed the document to the American people. It now hangs in the Lincoln Room of the White House.

Despite the Bliss copy being widely considered the standard version, it is quite possible that Lincoln did not stick exclusively to any of the five versions. The Nicolay version, which is the sole version thought to have been penned before the speech, may have been taken onstage. Matching folds in the two sheets suggest that the president may have pulled it out of a jacket pocket. However, he may have spontaneously added material. Several eyewitnesses recounted an aura of improvisation. "That is the emphasis in these accounts," Wills writes in Lincoln at Gettysburg, "that it was a product of the moment, struck off as Lincoln moved under destiny's guidance. Inspiration was shed on him in the presence of others."

The historical record, of course, paints Lincoln as a man of intense preparation. Improvisation would seem to go against his nature, and most historians agree that he wrote the first draft in Washington before November and revised it the night before the dedication. Still, a certain appeal lies in the idea of a "democratic muse" dictating one of America's great public commentaries, which almost never happened.

Lincoln had almost not been at Gettysburg to make his now-famous address. His staff had scheduled him to leave by train at 6 a.m. of the day of the dedication for the noon start. If he hadn't decided to leave a day early, he would almost certainly been delayed by the throngs that crowded the roads leading to the site.

By being there, Lincoln was able to revolutionize the very thinking behind the United States constitution. By basing the Gettysburg Address on the principles of equality and human rights in the Declaration of Independence, he appealed to the spirit of the constitution rather than its words. Its written tolerance of slavery excluded many from the full rights of citizenship. The speech subverted those words. Willmore Kendall, a conservative commentator of the day, commented that "Abraham Lincoln and, in considerable degree, the authors of the post-Civil War amendments, attempted a new act of founding, involving concretely a startling new interpretation of that principle of the founders which declared that "all men are created equal."

Lincoln stood on that platform with his long-standing goal to win the war ideologically as well as militarily. In many ways, he succeeded; most Americans today view the Civil War through his lens, the lens he crafted in part through the Gettysburg Address. Garry Wills put it so aptly: "Words had to complete the work of the guns."

Sources:

- “An Official Invitation to Gettysburg.” Library of Congress. 5 Dec. 2002. 25 Feb. 2008. <http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/trt031.html>.

- Borritt, G.S. The Gettysburg Gospel: The Lincoln Speech that Nobody Knows. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006.

- [Editorial]. Chicago Times 23 Nov. 1863. Louis A. Warren. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Declaration: “A New Birth of Freedom.” Fort Wayne, IN: Lincoln National Life Foundation, 1964. 148.

- [Editorial]. Chicago Tribune 20 Nov. 1863. Louis A. Warren. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Declaration: “A New Birth of Freedom.” Fort Wayne, IN: Lincoln National Life Foundation, 1964. 145.

- “Eyewitnesses at Gettysburg.” National Public Radio. 15 Feb. 1999. 25 Feb. 2008. <http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1045619>.

- Gopnik, Adam. “Angels and Ages.” The New Yorker. 28 May 2007: 30. <http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2007/05/28/070528fa_fact_gopnik>.

- “The Gettysburg Address.” Cornell University Library. 2002. 25 Feb. 2008. <http://rmc.library.cornell.edu/gettysburg/>.

- “The Gettysburg Address Drafts.” Library of Congress. 29 Sept. 2005. 25 Feb. 2008.<http://myloc.gov/Exhibitions/gettysburgaddress/Pages/default.aspx>.

- Toppo, Greg. “Honestly, is that really Abe in 3-D?” USA Today. 16 Nov. 2007: A3.

- Wills, Garry. Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words That Remade America. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992.