Almost everyone who thinks about Pennsylvania and the Civil War immediately thinks of the Battle of Gettysburg. What they may not know is that the outcome of that battle could have been significantly different had it not been for one encounter in the small York County town of Hanover. The Battle of Hanover tested the cavalry forces and artilleries of both the Union troops led by General Judson Kilpatrick and by the Confederates commanded by General J.E.B. Stuart. This confrontation delayed General Stuart’s armies’ arrival in Gettysburg until nightfall on the second day of the battle, forcing General Robert E. Lee to fight without the eyes of his cavalrymen and to succumb to eventual defeat.

The battle itself started with a wagon train. General Stuart was passing through Rockville, MD, on his way to Gettysburg when he heard news of a wagon train coming from Washington, DC, traveling north for Union General George Meade’s forces at Gettysburg. Stuart intercepted the train, which included 125 wagons full of supplies—a huge blow to the Union forces; but a silver lining would soon be realized.

The considerable booty commandeered by the rebels would slow down their troops making it more difficult to rendezvous with General Lee’s men for the planned attack on Gettysburg on July 1, 1863. According to Prelude to Gettysburg: Encounter at Hanover by the Hanover Chamber of Commerce, “to reach the same place Stuart must traverse more than ten miles; but an early start and an unimpeded march would have placed him in advance of his adversary. As it was, he struck the rear of [Union General Elon] Farnsworth’s brigade at about 10 o’clock on the morning of the 30th, in the town of Hanover.” The wagon train slowed General Stuart just enough to force a confrontation with part of the Union armies traveling through Hanover on their way to Gettysburg.

A spirited fight broke out that included hand-to-hand combat, cavalrymen riding horses, slashing sabers, and the use of an assortment of guns, ranging from small pistols to large cannons shooting artillery shells. Before the rebels slammed into the rear of a Union regiment on June 30, 1863, citizens were already prepared to meet the Confederates. According to the official Hanover newspaper, The Evening Sun, a farmer spread the word, yelling, “The enemy will soon be here! They are now in McSherrystown!” Citizens didn’t have time to react as the rebels arrived minutes after. The rebels were given the duty of destroying telegraph lines and bridges to delay the Union forces from reaching Gettysburg in time. Tom Huntington’s Pennsylvania Civil War Trails quotes the Reverend K. Zieber, the pastor at the Emmanuel Reformed Church and the head of Hanover’s Committee of Safety: “We received no newspaper; the telegraph wires were cut, and all we could learn of the movement of the Union of Confederate forces toward Gettysburg was gathered from rumors.” After the rebels left to disrupt a railroad north of Harrisburg, Hanover was left alone with no means of communication. Later General Kilpatrick’s forces would arrive to put citizenry at ease.

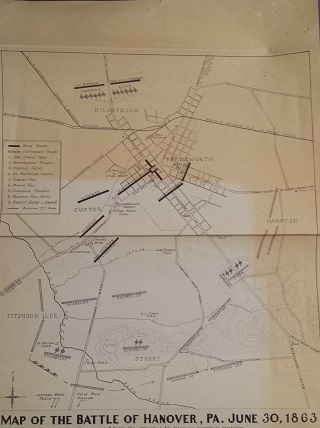

The Union regiments, who were resting in Hanover, received gifts such as food, cigarettes, and other supplies from the very patriotic and willing citizens. They were soon bombarded by rebels who cut the Union force in two, seizing the town in a very quick and forceful manner, driving the Union troops out of town. General Kilpatrick and the troops he led had already passed through Hanover, when a messenger delivered a letter from General Alfred Pleasanton in Maryland that warned him of a possible rebel engagement. As soon as he read the warning, the first shot signaling the start of the Battle of Hanover was heard, compelling Kilpatrick to countermarch his troops back to Hanover. General Farnsworth’s men of blue drove the rebels back out of the town just in time for Kilpatrick’s forces to occupy it. With the help of the citizens, the Union soldiers barricaded the streets with anything they could find. According to The Prelude to Gettysburg: Encounter at Hanover, “Baltimore, York, and Frederick Streets were blocked with store boxes, wagons, hay ladders, fence rails, barrels, bar iron and anything that would prevent the enemy from dashing into town.” Each side took up defensive positions on each side of town during the lull. The Union set up artillery cannons on Bunker Hill west of the Carlisle turnpike to the rear of the present Eichelberger High School; the Confederates set up their artillery cannons on Baltimore Pike near the Mount Olivet Cemetery.

©Christopher Birster

©Christopher BirsterNot so long after each side was set up, artillery shells started raining over the town. Tom Huntington quotes Ambrose M. Schmidt, a boy who was in Hanover at the time with his mother, and a Union cavalry soldier. Schmidt remembered, “Suddenly, a shell exploded in the direction of Frederick Street. He at once leaped to his feet, ran to his horse, and exclaimed, ‘My God, woman, the Confederates are upon us! Get your children into the house.’ He then dashed out Abbotstown Street. We could not have been there more than a few moments when the cavalry forces met on Broadway, right before us. We ran into the house, crying.” This artillery duel lasted for a couple of hours, while all the while General Stuart was adamant about protecting his prize of wagon trains. He decided the town was too well-guarded for him to pursue. He called upon one of his officers to take his plunder through the village of Jefferson to York and eventually to Gettysburg.

The capture of the train of wagons was a misfortune for the Union army. But it delayed Stuart from meeting up with General Lee at Gettysburg. General Farnsworth drove the rebels from town where they had to backtrack and take a longer way to Gettysburg. As Farnsworth drove the rebels out of town, Stuart and his men were cut off on the road and had to leap a ditch. Stuart retired to the hills south and east of Hanover, which gave him a good position that caused the Union forces to stop their own advances. Kilpatrick kept a presence in front of Hanover. He moved northward the next day to Abbotstown and sent an officer to follow Stuart’s trail as far as Rossville unknowingly by Stuart. The night march to Jefferson proved difficult as the wagons and passengers were a hindrance; they had nearly 400 prisoners. The mules were starving for food and water, making them unmanageable. The prisoners who were driving the train kept falling asleep, making every rebel officer’s job more difficult to keep the train in motion.

After the battle, the newspaper at the time, according to The Prelude to Gettysburg: Encounter at Hanover, called the Hanover Spectator wrote about the war. The Spectator’s account follows: “Our town on Tuesday for the first time saw and felt all the incidents, scenes, and horrors of actual war.” Local historian John Krepps recounts that the citizenry rose to the occasion; he told York Dispatch reporter Erin James that “Hanover's civilians, especially the women, received an unusual number of accolades for that heroism.”

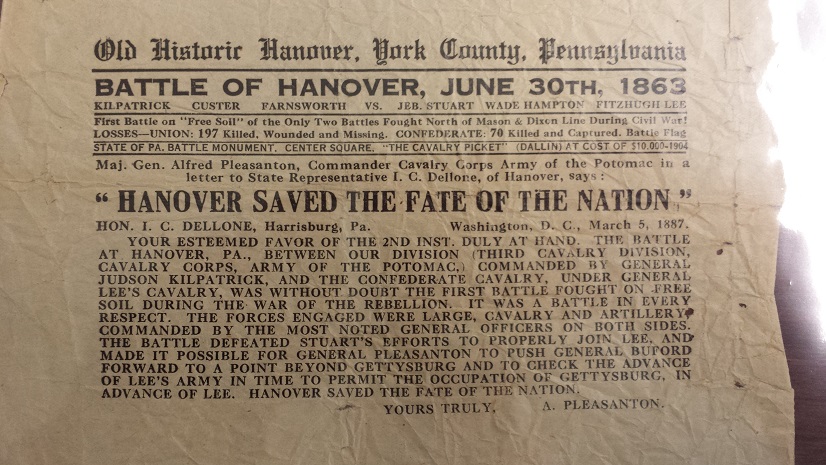

Kilpatrick wrote down the casualties he endured during the battle. He reported having two officers killed, six wounded, and five missing. The enlisted men included seventeen killed, thirty-five wounded, and 118 missing. The total Union casualties were 197 killed, wounded, missing. The report also includes the enemy having an upward of twenty killed, fifty taken as prisoners, and one captured battle flag.

In 1887, Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasanton wrote to PA State Representative I.C. Dellone that “Hanover saved the fate of the nation.” Local historians J. David Petruzzi and John Krepps very much agree with the general on the encounter at Hanover being vital in the outcome of the battle at nearby Gettysburg. Even well-known national historian James McPherson is quoted as saying the engagement “…delayed Stuart. His late arrival probably had an impact, with the wear and tear on his horses and the casualties suffered in Hanover.” Others acknowledge its part, but largely in conjunction with the delay caused by Stuart’s capture of the slow-moving wagons in Maryland.

In 2013, the 150th anniversary of the battle was commemorated throughout the Hanover area. The major feature of the festivities was a re-enactment of the battle on the Sheppard farm south of Hanover. While some phases of the battle had indeed taken place in the open countryside, most of it had occurred in the town itself, making an on-site re-enactment impossible. Heather Sheppard said of the re-enactment: “It’s really for locals. A lot of locals don’t go to Gettysburg because they know it’s going to be nuts so this is for them.” She added, as Lillian Reed reported in the Hanover Evening Sun, that “she wanted her kids to know that the town they came from was an important place.” Periodic re-creations of the battle and historians’ increased attention on the battle continue to support that goal.

Sources:

- Charisse, Marc. “Cavalry troopers to maneuver on actual battle ground for Hanover re-enactment.” Hanover Evening Sun 1 Jun. 2013.

- “Farmer Gave Hanover Word Of Invasion.” The Evening Sun 22 Jun. 1963.

- Hanover Chamber of Commerce. Prelude to Gettysburg: Encounter at Hanover. Shippensburg: Burd Street Press, 1963.

- Hanover Community Bi-Centennial Corporation. Official program of the bicentennial of the founding of Hanover and the centennial of the Battle of Hanover with historical sketches & pictures June 23-30, 1963. Hanover: Hanover Community Bi-Centennial Corporation, 1963. 7-23.

- Huntington, Tom. Pennsylvania Civil War Trails: The Guide to Battle Sites, Monument Museums and Towns. Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 2007. 87-97.

- James, Erin. “Re-enacted in hay field, Battle of Hanover was fought in the streets.” York Dispatch 2 Jul. 2013.

- “Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasanton, Commander Calvary Corps Army of the Potomac in a letter to State Representative I.C. Dellone, of Hanover.” The Evening Sun 22 June 1963 [Hanover, PA].

- Reed, Lillian. “Battle re-enactment at Hanover held ‘with military precision.’” Hanover Evening Sun 2 Jul. 2013.

- Sheffer, John M. The Battle of Hanover June 30, 1863. Map. (1962). Print.