In an episode of the children’s television show, Thomas the Tank Engine once said “Little engines can do big things.” This is a perfect way to describe the humble beginnings of the locomotive industry. In today’s America cars get you wherever you need to go and planes take you across the globe, while trains are left mostly to subway systems or commuter rails. Even where there are cross-country trains, they have evolved far beyond the classic steam engine, like the TGV in France that reaches speeds of well over 300 miles per hour, roughly 30 times faster than early American trains. With beginnings in northeastern Pennsylvania’s Wayne County, steam engine locomotives have played an integral part in adding chapters to both American and technological history.

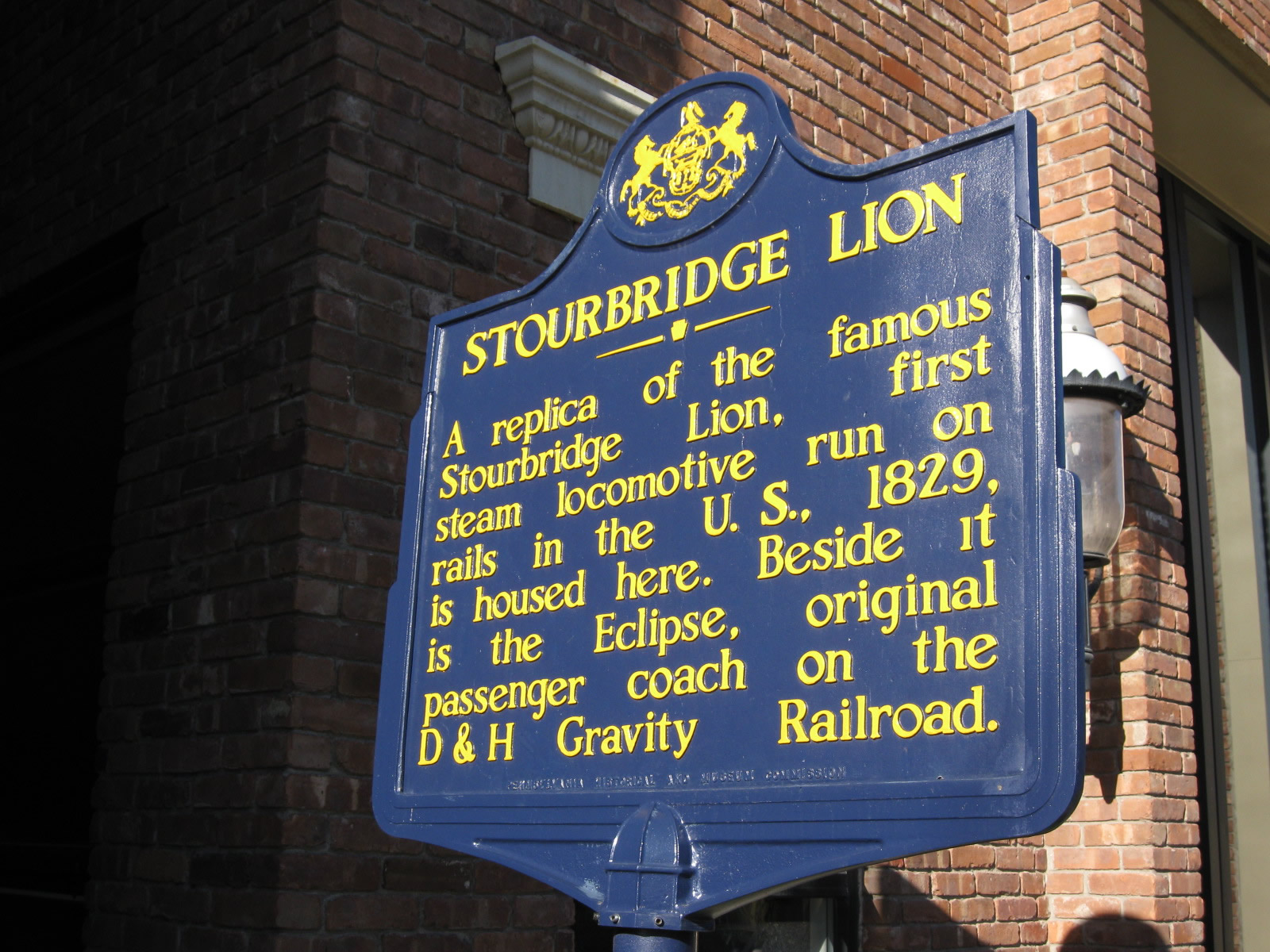

Trains came along as a result of the invention of the steam engine during the industrial revolution. British engineer George Stephenson, renowned as the “Father of the Railways,” completed building the first steam engine locomotive in 1814. The first practical use of these locomotives came 11 years later in 1825. The locomotive credited for being the first steam engine in America was also a British train, shipped to New York from England in 1829. Though it was not American-built, it was the first such locomotive to operate on American soil. This locomotive was the “Stourbridge Lion,” and it marked the official beginnings of an American industry that would lead to vast advancements in the decades that followed

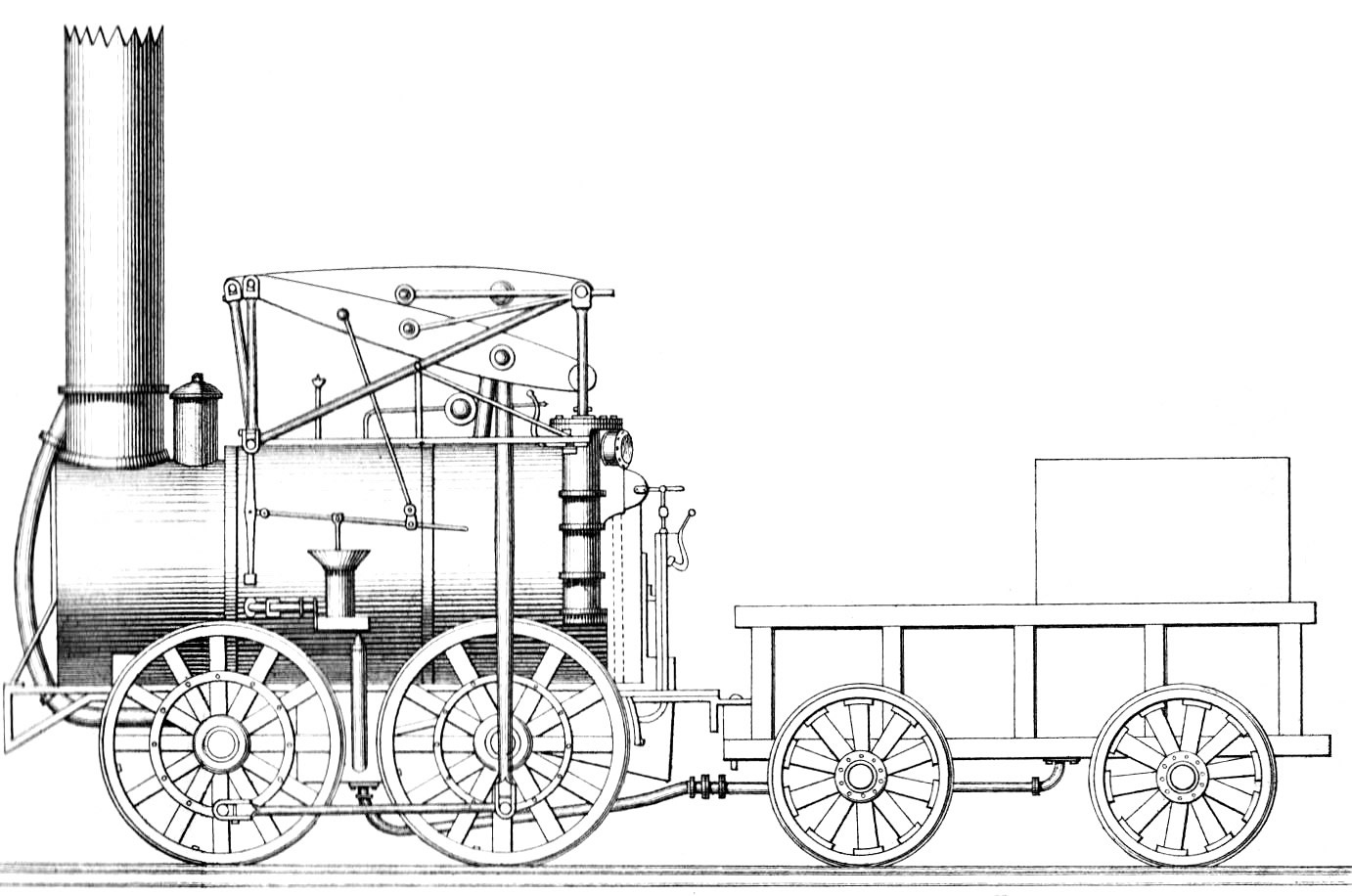

The Stourbridge Lion was one of four locomotives to be originally ordered from England, but it was the only one that ended up actually operating. It was also not the first locomotive to be sent from England, that title goes to the “Pride of Newcastle,” which arrived nearly two months earlier. The Stourbridge Lion was named for the location of its manufacturer and the lion that was painted on the front. The design was plain and utilized simple thermodynamic principles. The pistons in the engine were connected to walking beams mounted above the boiler. A driving rod was then connected to both the front and rear axles, which was how the locomotive utilized the steam engine to produce motion by turning the wheels.

In the years prior to the engine’s arrival, William Wurts, a Philadelphia merchant, realized that there was a lot of value in the anthracite coal fields in the area around Carbondale, Lackawanna County. At the time, New York City was struggling with restrictions on the import of British bituminous coal, upon which it depended. Wurts thought of building a canal to connect the coal fields of Carbondale to Kingston, New York where it was then taken by canal to supply the city. Out of this idea came the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company, which was opened to navigation in 1828. The company then went on to build a railroad, on which originally ran unpowered gravity-driven trains to carry the coal over the Moosic Mountains to the canal at Honesdale. It was then that the historic maiden voyage of the American steam engine took place.

Honesdale, a borough in Wayne County, has come to be known as the birthplace of American railroading because it is the site of the very first run of a steam engine locomotive in the United States. Located northeast of Carbondale not far from the New York state border, Honesdale was an important location in the transport of coal both before and after the steam engine. It began as the site of the gravity railroads, where coal would arrive from the mountains to be shipped by canal. Later, the state of Pennsylvania authorized the construction of a railroad to be used by steam engines. This ran from Honesdale to Kingston, New York, and the company hoped its construction would make it possible for coal to be transported to the canals faster. It was on this track that the steam engine would enter into American history.

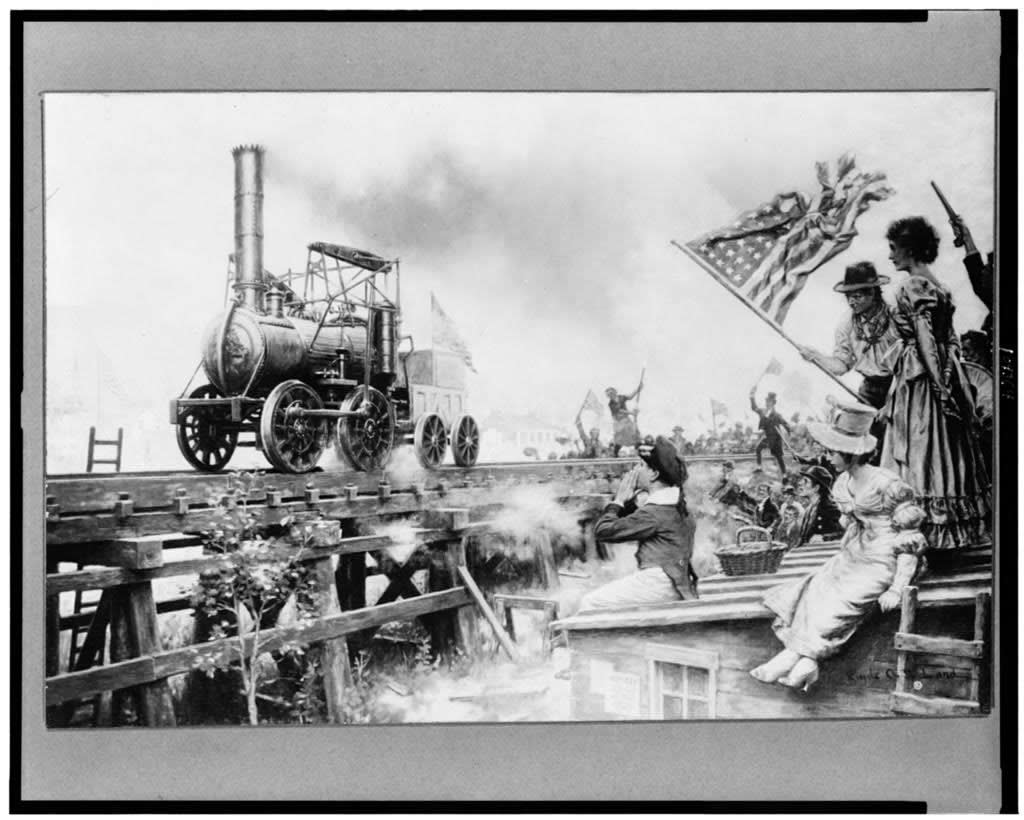

The historic first run of the Stourbridge Lion took place on August 8, 1829 in Honesdale. This milestone journey totaled six miles round-trip as the train made its way to and from nearby Seelyville. The engine itself performed well in its first test, but it ran on a track that was built to support four tons, when the Stourbridge Lion weighed nearly seven and a half tons. This could possibly be the reason that the Stourbridge Lion did not go on to carry passenger trains. The actual Stourbridge Lion engine has largely been lost. By 1845, only the boiler remained. Some parts of the train are currently in possession of the Smithsonian Institution, although there are some doubts as to the authenticity of these parts as some may be from replicas that were created in the years following the 1829 test run.

Further developments in American steam engine locomotives followed soon after the arrival of the Stourbridge Lion. One of the more notable engines that followed was nicknamed “Tom Thumb” because of its small size. Peter Cooper, a merchant from New York City built Tom Thumb because the directors of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad had investigated the tests of the Stourbridge Lion, and decided there was nothing to lose in investing in a second model. Cooper bought a small steam engine, built a boiler out of iron, and used two old musket barrels for boiler flues. Tom Thumb was meant simply to show that rotary motion could be achieved without using a crank, and that short turns could be made. Cooper did not intend for the engine to be used for actual service.

Just 395 days after the Stourbridge Lion’s run, Tom Thumb officially began the first trip by an American-built locomotive, journeying from Baltimore to Ellicott’s Mills. The engine carried six men plus an additional passenger car with 36 men. The trip in total took 72 minutes, with the train averaging five and a half miles per hour. What was more interesting was the return trip. On this trip, Tom Thumb demonstrated its ability to take short turns without slowing down much below 15 miles an hour, and reached a maximum speed that day of 18 miles per hour. It was a peculiar event that solidified Tom Thumb’s place in history and removed all doubt that trains would soon take over as the best mode of transportation of the day.

At the halfway point of the journey, while refueling, proprietors of the Baltimore & Ohio railroad, Stockton and Stokes, who were confident that horses still had superiority over this new form of technology challenged Tom Thumb to a race. The men with Tom Thumb accepted the challenge and agreed to race against the horse. At times, the race was neck and neck, but eventually Tom Thumb took the lead. Despite this, a band driving a pulley slipped from the drum, which caused the engine to malfunction, and thus allowed the horse to win the race. Even though the horse won, Tom Thumb demonstrated the capability to move faster, and it would only take a slight tweak to prevent a similar malfunction to make transportation by horse and horse drawn carriage obsolete.

The development of the steam engine dramatically improved the ability to travel. As the models moved forward, it became easier to travel longer distances in shorter periods of time. The Baltimore & Ohio railroad itself connected several states in the northern United States, reducing travel times between these places from days to hours. The construction and implementation of the transcontinental railroad was a major development that continued to improve this new form of transportation. By 1869, when the railroad was completed, four decades had passed since the initial run of the Stourbridge Lion. Steam engines and trains were no longer an experimental idea; they were becoming a very important method of travel.

The transcontinental railroad spans much of the western half of the country from Council Bluffs, Iowa to Sacramento, California, was built during the Civil War to unite the East and the West. It was built as two separate railroads heading east and west, with the celebratory connection at Promontory Point, Utah. It revolutionized the westward migration that was in progress in the United States. No longer would migrants need to withstand months of hazardous travelling in covered wagons on the Oregon and California Trails. Interestingly enough, it would be a Pennsylvania company, the Baldwin Locomotive Company, that would be the leading maker of train engines for the remainder of the train era.

Who knew that so much could come from what originated as a simple thermodynamic model? This simple model was brought to life first in England, and later in America in the form of locomotives and these locomotives went on to revolutionize travel as they were part of an early step in making the globe smaller. From simple test runs and horse races to railroads connecting two halves of the nation, from barely going above 15 miles an hour to speeds up to 20 times that; the steam engine certainly has come a long way since the Honesdale test ride of the Stourbridge Lion.

Sources:

- Atack, Jeremy. “The Regional Diffusion and Adoption of the Steam Engine in American Manufacturing.” The Journal of Economic History 40 (1980): 281-308.

- Crosby, David. Scranton Railroads. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2009.

- Hoexter, Corinne K. “A Colorful Corner of Pennsylvania.” New York Times. 31 May 1987: A21.

- Kinert, Reed. Early American Steam Locomotives. New York: Crown Publishers, 1962.

- Lamb, J. Parker. Perfecting the American Steam Locomotive. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003.

- Sinclair, Angus. Development of the Locomotive Engine. New York: Angus Sinclair Publishing, 1907.

- Temin, Peter. “Steam and Waterpower in the Early Nineteenth Century.” The Journal of Economic History 26 (1996): 187-205.