Fedders, Proprietor, Plainandsimplequilts.com

I must be a Christian child,

Gentle, patient, meek, and mild;

Must be honest, simple, true

In my words and actions too.

I must cheerfully obey,

Giving up my will and way.

-A traditional Amish school verse

Lancaster County is home to the most well-known Old Order Amish communities in the North America. In 2000, an estimated four million tourists visited this county hoping to experience a bucolic slice of Amish life. There is no doubting that the Amish are disproportionately financially and culturally important to this area.

From a 1959 tourist guide book advertising the "quaint" and "simple" practices of the Amish to the 1985 movie Witness, the curiosity of outsiders has grown, while impressions of the Amish—a simple, quiet people rejecting modernity—have remained largely static and simplified. A better understanding of the core values and aspirations of this group exposes a complex culture, approaching modern values and technology in a remarkably different way than the rest of society.

In the 1940s and 1950s sociologists declared that the Amish were a culture in decline that would soon disintegrate under the pressures of technology and urbanization. Contrary to these predictions, the Amish flourished in the second half of the twentieth century. The Old Order Amish population in Lancaster County, a mere 4,100 in 1950, grew exponentially to 22,300 by 2000. This was part of a national trend of growth.

A significantly above average birthrate contributes to this increase, as does a remarkable retention rate—90% of children who are born Amish choose to remain Amish. Those who admire the Amish suggest the high retention rate as evidence of the superiority of leading a simple, traditional existence, while critics maintain that the nature of education and home life leave Amish youth with few viable alternatives. Either way, trends suggest that the Amish will not be disappearing any time soon.

The resiliency of this group can be attributed to the strength of its identity. Members commit to live according to well-defined core religious and social values and hold the preservation of these values to be essential. According to sociologist Donald Kraybill, "religious meanings pervade the fabric of Amish life." The Amish hope to model their lives after a straightforward interpretation of the New Testament by practicing Gelassenheit—submitting or yielding to a higher authority and, ultimately, to God. Humility, simplicity, obedience, and self-discipline are keystone values in the Amish community and inculcate this submission.

The uniquely traditional dress and technology of the Amish are important symbols of humility, simplicity, and the submission to community, which juxtapose sharply with the ambition and individuality that they view as inherent in modern American culture. Standardized Amish garbs prevent expressions of individuality and reinforce equality between members. Subtle differences in dress within groups also provide indicators of important information like age and marital status, while differences in dress between Amish congregations can convey how "plain" or orthodox each one is.

The horse-and-buggy carriage, a technology commonly associated with the Amish, engenders important cultural values. The limited speed and durability of horses makes these carriages incapable of traveling far from home. This is meant to keep the scale of the community small. Some Old Order Amish will ride in the car of a non-Amish neighbor, usually for business purposes, but ownership is strictly forbidden.

In matters of technology, Amish businesses are often fairly flexible. As with cars, many Amish will use local payphones for business and long-distance calls, but ownership of a convenient home phone is forbidden for fear that it might replace face-to-face communication within the community. Technologies that are used in the home or affect the home are more scrutinized because family life is viewed as the foundation of Amish society.

Debates over the use of new technologies are a constant process and the results are not universal across Amish communities. Occasionally, these debates facilitate the formation of new Amish sects. The orthodoxy of a specific community is often indicated by what technologies are accepted. In an area like Lancaster County, a discerning visitor is likely to observe a wide-range of technology use between different Amish congregations.

The religious rituals in Amish life are endowed with the values of humility and simplicity. Old Order church services are held in the homes of members on a rotating basis. When a congregation becomes too large to fit in a single home, a new congregation is usually formed to maintain the small scale of the services. The Amish are congregational, meaning that there is no formal religious structure or organization beyond the local level.

The Amish derive from the Anabaptist tradition and practice adult baptism, meaning that one must choose church membership as an adult. Rumspringa, the period before an Amish youth officially joins or leaves the church, can be used for experimenting with the values of the "English" world. In this context, tourists are often baffled when they see young Amish driving cars, talking on cell phones, and wearing jeans.

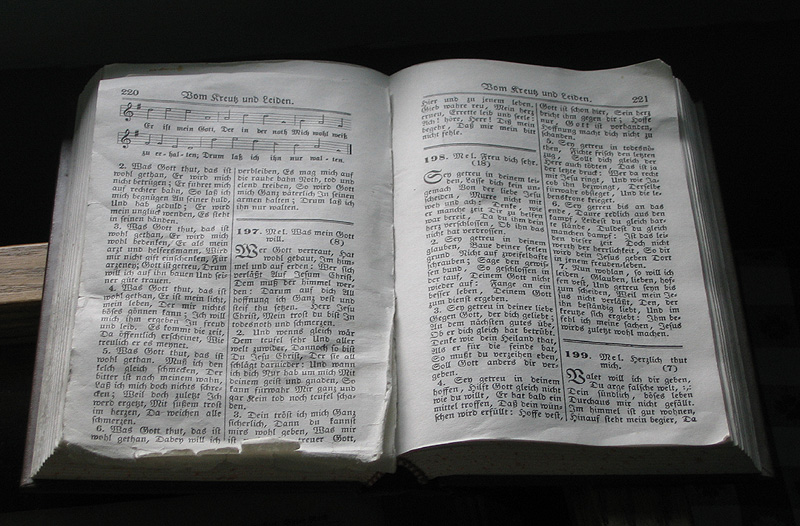

Religious services are generally held every other Sunday and typically last from the morning into the early afternoon. Traditional hymns from the Ausbund—an Amish book of songs dating back to the 1600s—are sung and several sermons and Bible readings are included. The service is usually led by a Bishop, which is a lifelong appointment chosen by drawing lots. The ritual of "visiting" is practiced on Sundays when there is no service. A "visit" is usually a low-key affair spent discussing community issues and enjoying homemade treats.

Agriculture is the bedrock of the Amish lifestyle and economy. Sociologist John A. Hostetler claimed that "soil has, for the Amish, spiritual significance." The practical benefits of small-scale farming from an Amish viewpoint—the rural setting that it requires, the simple values that it teaches, the hard work that it demands—are complemented by a commitment to tending to and protecting God's land, guided by the Old Testament principle of stewardship. The Amish connection to the land also dictates the pace and rhythm of Amish life. For example, weddings are usually held during the winter months to avoid interfering with the busy planting and harvesting seasons.

The massive growth of the Amish population coupled with the skyrocketing cost of farmland has necessitated an increasingly diverse array of non-agricultural jobs in many Amish communities, including Lancaster County. Although it varies by community, many unmarried Amish men work as carpenters, blacksmiths, or even on assembly lines in factories. In Lancaster County, most of these young men work within the Amish community, but it is also not uncommon in other communities for a majority to work for non-Amish businesses. These jobs are also often taken with the eventual goal of saving money to purchase farmland, an indication that agriculture remains the ideal profession of the Amish.

The skills traditionally emphasized by modern American education, such as literacy, critical analysis, and scientific rationality, are not the focus of Amish schooling. Amish one-room schoolhouses are not dramatically different than rural schools throughout early the twentieth-century U.S. In fact, until the 1930s, the Amish largely attended local public schools.

Basic literacy and arithmetic, essential skills for running a successful farm, are taught in Amish parochial schools. Some studies have found Amish children to be more proficient in these areas than "English" peers. The Amish shun higher-learning as prideful and withdraw children from school after eighth grade, believing that to be an appropriate time to begin learning the necessary skills of farming and home-making through experience.

The consolidation of rural public schools and the enforcement of mandatory schooling laws led to a drawn out struggle between the Amish and state authorities. From the 1940s until the 1970s, newspapers printed pictures of Amish men being brought to jail in handcuffs for refusing to send their children to public high schools. Despite arguments by state officials that Amish education limited the possibilities of its pupils, Wisconsin v. Yoder, a 1972 U.S. Supreme Court case, affirmed the Amish right to establish and run their own schools as a matter of religious freedom. The Amish have clashed with state and national governments over a host of other issues, including: military conscription, social security taxes, and mandatory insurance.

Any characterization of the Amish as either outside of modern concerns and problems or as religiously backward is, at best, an exaggerated idealization. Those who idealize in this way often use a simplified version of the Amish to serve a personal agenda. One key aspect of Amish values, maintaining a respectful separation from the non-Amish, has prevented them from shaping or changing their public image significantly. The Amish, who are uniquely tied to Lancaster County where they first settled, deserve to be recognized and studied as a unique American subculture.

Sources:

- Buck, Roy C. "Boundary Maintenance Revisited: Tourist Experience in an Old Order Amish Community." Rural Sociology. 43, 2 (1978): 221-234.

- Hostetler, John A., ed. Amish Roots: A Treasury of History, Wisdom, and Lore. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989.

- ______________. Amish Society, Fourth Edition. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.

- Hostetler, John A. and Gertrude Enders Huntington. Amish Children: Education in the Family, School, and Community, Second Edition. Fort Worth, Tex.: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1992.

- Kraybill, Donald B. The Riddle of Amish Culture, Revised Edition. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

- _______________. "Negotiating with Caesar." The Amish and the State, Second Edition. Ed. Donald B. Kraybill. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003. 3-22.

- Nolt, Steven M. A History of the Amish. Intercourse, Pa.: Good Books, 1993.

- The Pennsylvania Dutch Tourist Bureau, comp. and ed. Pennsylvania Dutch Guide Book. Lancaster: The Pennsylvania Dutch Tourist Bureau, 1959.

- Weaver-Zercher, David. The Amish in the American Imagination. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

- Yoder, Paton. "The Amish View of the State." The Amish and the State, Second Edition. Ed. Donald B. Kraybill. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2003. 23-42.