Since the 1800s, when industrial advancements led to the growth of booming, densely populated cities, American families have been looking for ways to escape the hustle and bustle of city life. Amusement Parks have long been cherished destinations for such adventures. The light hearted, whimsical atmosphere offered by amusement parks is irresistible to people of all ages and can bring out the child in just about anyone. Nestled in the Laurel Mountains of Ligonier, Westmoreland County, Idlewild is the oldest amusement park in Pennsylvania, the 3rd oldest in America, and the 12th oldest in the world.

Idlewild is the perfect destination for a scenic, action filled family getaway. Although not greatly known across the country, Idlewild has earned some impressive accolades. It was voted among the top five parks for families by the National Amusement Park Historical Association and it was voted second-best kids’ park in 2009 for the sixth consecutive time by Amusement Today.

Since its creation in 1878, Idlewild has been known and loved for its natural beauty and graceful balance of man-made attractions and lush, dense wilderness. Gerard DeFlitch of the Pittsburgh Tribune Review describes how, “It was under that naturally aesthetic umbrella that Idlewild Park was gently carved into the peaceful landscape.” Sandy Smetanka, daughter of Idlewild’s superintendent, recalls growing up on the park grounds: “It was like living in a candy store, […] The woodland setting makes Idlewild what it is and it’s great that it’s not so commercial.” These attributes are what have made Idlewild a favorite destination for Pennsylvanians for over one hundred years.

Idlewild Park owes its creation to an entrepreneurial visionary named Judge Thomas Mellon. Mellon, founder of T. Mellon and Sons Bank in Pittsburgh and large financial supporter of corporate titans such as Gulf Oil, Alcoa, Westinghouse Electric, and PPG Industries, purchased the partially completed Ligonier Valley Railroad at a sheriff’s sale in 1875. The railroad was originally built to transport coal and timber to Pittsburgh and surrounding areas. Mellon’s economic ambition led him to expand the operation to include passenger transportation, allowing for city dwellers to enjoy the scenic woodlands of the Laurel Mountains.

Mellon soon inquired to purchase a plot of land from William M. Darlington. The site was a 350 acre plot in a wooded mountain valley, split by the serene Loyalhanna creek. In 1878, Darlington wrote to Mellon, “In compliance with your request, I will and do hereby agree to grant to the Ligonier Valley Rail Road Company the right and privilege to occupy for picnic purposes or pleasure grounds that portion of land in Ligonier Township, Westmoreland County […] provided no timber or other trees are to be cut or injured – the underbrush you may clear out if you wish to do so.” With this agreement, Idlewild was born.

This plot of land is of particular historical significance. During the French and Indian War, Fort Ligonier was constructed along Loyalhanna creek as a supply post for the final attack on Fort Duquesne, a French-occupied fort in what would become Pittsburgh. In November 1758, a group of volunteer Virginia militia led by Colonel George Washington was stationed at Fort Ligonier. Washington received news that a group of American troops, led by Lieutenant Colonel Mercer, was under attack a few miles away. Washington and his troops were sent to the aid of Mercer and his men. By the time they reached the site of the skirmish, dusk had fallen and the enemy had retreated. Cloaked by darkness, Washington and his troops were mistaken for the enemy and fired upon by Mercer’s men. Many American soldiers were killed before Washington ran through his ranks, knocking up his soldiers’ muskets with his sword to end the skirmish. This account is taken from a narrative written by George Washington himself. In his report, Washington claims that between those firing lines his life was never in more imminent danger. This unfortunate exchange of friendly fire is believed to have taken place on the land that would become Idlewild.

In its early days, Idlewild was more of a nature park than a theme park. Original attractions included camping, hiking trails, bicycle courses, ball fields, tennis courts, shaded walks, and picnic pavilions. Between 1880 and 1896, three lakes were dug, adding fishing and boating to the park’s activities. One of these lakes, Lake Bouquet, encloses a large island called Flower Island. Thousands of species of flowers, grasses, and shrubs were planted here to make Flower Island a true botanist’s paradise. There were only a few buildings originally, including an auditorium, a dance hall, a dining hall, a boathouse, and a pavilion. Idlewild’s popularity grew rapidly as word spread about the scenic wilderness offered by the park. According to a Ligonier Echo article from 1890, describing that summer’s Fourth of July, the trains to Idlewild were so crowded that, “the tops of the coaches were covered with boys.”

The park’s natural appeal was not the only reason for its growth and success. Mellon advertised heavily throughout Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania. Idlewild: A Story of a Mountain Park, a promotional brochure printed in 1900 states, “The woods and dells, the trees and shrubs and flowers bid you be happy; bid you cast care and the world to the winds and woo contentment and repose in nature’s arms.” Idlewild catered to family picnics as well as large group outings. According to records, groups of over 1,200 guests would board the rails for a single visit. Upon the death of Judge Thomas Mellon in 1908, his sons, Andrew and Richard took control of the Park.

The duo continued in their father’s footsteps until 1931, when Idlewild was sold to the Idlewild Management Company, a partnership between Richard Mellon and Clinton Macdonald. Andrew Mellon had gone on to become the Secretary of the United States Treasury under presidents Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover. The new partner, Macdonald, had over 30 years of amusement park experience and would later become the park’s general manager. Until this point, the only rides offered consisted of two carousels. Macdonald began to reinvigorate Idlewild by bringing electricity to the park and adding concession stands, a giant swimming pool, and several amusement rides: a new carousel, a circle swing, a Ferris wheel, a Whip, a miniature railroad, and the main attraction, a wooden roller coaster named the Rollo Coaster. The Rollo Coaster is a classic wooden coaster that cuts through Idlewild’s woodlands, providing an exciting roller coaster experience to riders of all ages. Macdonald brought in traveling performance shows such as circuses, rodeos, and fireworks displays to entertain patrons. He also made large investments in landscaping to further the natural beauty offered by the park.

The early 1940’s marked the beginning of the America’s involvement in World War II. This commitment led to national rationing that began to hinder Idlewild’s operation. By 1943, Macdonald decided the most economically logical response would be to temporarily close the park; it remained closed for the remainder of the war. With the war drawing to an end in 1945, Macdonald spent $50,000 renovating the park, reopening in May 1946. The Caterpillar was introduced to park patrons in 1947 and still operates today. It is one of only a handful still in operation and of only three with an operating canopy. By 1950, Macdonald had purchased the land and the park, assuming complete control of Idlewild.

In 1952, the Ligonier Valley Railroad, a key element of Idlewild’s birth and growth, was abandoned. By this time the automobile was a household amenity and the Lincoln Highway had been constructed. The Lincoln Highway spanned from New York City to San Francisco and ran right past Idlewild. The closing of the coal mines in the area, combined with a decline in passenger traffic marked the end for the historic Railroad.

In 1956, Macdonald teamed up with Arthur Jennings, a performance clown at Idlewild, to expand the park and capture a new market created by the baby boomers by adding an attraction designed for children. They conceived the Story Book Forest, which was largely inspired by a roadside attraction in New England that Macdonald had visited. The Story Book Forest is a section of the park themed around fairy tales which features objects and characters from children’s stories and nursery rhymes. This addition was a huge success and greatly boosted park attendance, ushering in eighty-four thousand patrons in its inaugural season.

Macdonald’s adherence to the park’s traditional values, paired with his expansive ambition, allowed the park to grow and prosper through some of the toughest times in our nation’s history, including the Great Depression and World War II. In 1957, Macdonald passed away and left the park to his sons, Jack and Dick. The pair continued with their father’s expansive ambition, adding several new rides and attractions throughout their tenure. These included a zoo called Frontier Safari, a colonial town called the Historic Village, and a miniature train ride called the Loyalhanna Express. They also introduced the Ligonier Highland Games to the park in 1959.

The Ligonier Highland Games is an annual event honoring the soldiers of the 42nd Highland Regiment, also known as the Black Watch Regiment, who served in the French and Indian War. This was a Scottish regiment led by General Forbes that was stationed at Fort Ligonier. General Forbes led the Black Watch to the French Occupied Fort Duquesne and in 1758, Forbes and his men defeated the French and burned Fort Duquesne to the ground. This area, where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers meet to form the Ohio River, would be settled and named Pittsburgh after the British Prime Minister, William Pitt. The Ligonier Highland Games includes bands, dancers, and athletes who gather to compete and honor many aspects of Scottish culture. The competition includes many track and field events and many events rewarding strength and power, such as the hammer throw, the stone putt, and the caber toss, which involves flipping 14 to 17 foot tree trunks end over end. Currently, annual attendance of the Ligonier Highland Games averages about 10,000.

After years of operating and expanding the park, the Macdonald Family put Idlewild up for sale in 1982. In 1983, the Kennywood Entertainment Corporation, operators of West Mifflin’s Kennywood Park, bought the park. The first addition made by the new management was the Jumpin’ Jungle. This attraction includes a large tree house with climbing nets and other obstacles for children to conquer. They proceeded to relocate the Historic Village and remodeled it after an old Wild West town under the new name, Hootin’ Holler. The H2Ohhhh Zone, a waterslide facility, was added in 1985, increasing Idlewild’s allure. The largest contribution made by the new management, and the largest single investment made to the park at the time, was the addition of Mister Rogers Neighborhood in 1989. The million dollar attraction involves a trolley ride through a re-creation of the settings of the hugely popular children’s show, Mister Rogers Neighborhood. The experience offers an interactive experience with many of the characters from the show as well.

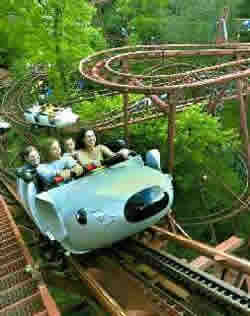

The park went through some reconstruction in 1990 to improve its roads and facilities. This included the creation of Raccoon Lagoon, a kiddy area offering several rides designed for younger children. In 1993, the park’s second roller coaster was added, the Wild Mouse. This is the park’s one and only steel roller coaster. Built into the wooded landscape, the Wild Mouse twists, turns, dips, and dives through Idlewild’s massive trees, providing riders with an exhilarating experience. In response to the growing popularity of the H2Ohhhh Zone, Idlewild’s largest investment doubled the size of the water park and renamed it Soak Zone. The expansion included six new waterslides and a 300 gallon water bucket that tips over periodically, drenching the swimmers below.

The Kennywood Entertainment Corporation has remained faithful to the ideals of the previous park owners and has certainly done a great job improving the park while maintaining the park’s original values. This point is illustrated by Jeffrey Croushore, Idlewild’s Public Relations and Marketing Manager, ““Idlewild is the finest, family-oriented entertainment facility in the country, […] It is a privilege for me to promote Idlewild’s fundamental ideals of family fun and nature’s true beauty.” Dick Macdonald, former park owner, voiced his pleasure with the Kennywood Entertainment Corporation; “I remember the days when there wasn’t any electricity here and we used to run the cows across the creek. I’ve been so happy to see what Kennywood has done for us.”

Today, Idlewild offers a wide variety of rides and attractions while maintaining the quaint, fanciful feel it has enjoyed throughout its history. The park’s General Manager, Brandon Leonatti, provides a great description of the park: “While Idlewild & SoakZone appeals to people of all ages, it is especially appealing to families with young children because we go to great lengths to carefully balance our low- tech classic attractions such as Story Book Forest with unique ones like Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood of Make-Believe and more high-tech attractions like Captain Kidd’s Adventure Galley. It’s nice to know that as America’s third oldest amusement park, we have the admiration of our peers and still create summer fun memories that last a lifetime for three and four generations of families.” Idlewild offers seven different themed sections of the park, with each providing a unique atmosphere and personality: Story Book Forest, Hootin’ Holler, Jumpin’ Jungle, Soak Zone, Raccoon Lagoon, Mister Rogers Neighborhood, and Olde Idlewild, which holds most of the park’s original rides, attractions, and buildings. There is certainly no shortage of activities to be enjoyed at Idlewild and the experience is one that no Pennsylvanian family should go without.

There are many amusement parks in the world, but none provide quite the same atmosphere as Idlewild. The strict adherence to the founders’ vision of a family and nature oriented theme park is what sets Idlewild apart. Leonatti describes how, ““The chief reason for Idlewild Park’s success for nearly 130 years - and why it is recognized as one of the best Parks in the world for families and kids - is that we never forget our roots, carefully blend the best of the old and new and strive to be part of the fabric of the communities in which we do business.” This lack of over-commercialization is a quality not to be overlooked in this day and age. A trip to Idlewild provides a look at our past, as well as a reminder of the family values our nation was built upon.

Sources:

- Albert, George D. “Fort Ligonier.” The Frontier Forts of Western Pennsylvania 2 (1896): 204-06.

- Croushore, Jeffrey S. Idlewild. Portsmouth, NH: Arcadia, 2004.

- DeFlitch, Gerard. “Idlewild Park’s 125th Anniversary Gathers Familiar Faces.” TRIBLIVE. Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, 16 June 2002. Web. 02 June 2010. http://www.pittsburghlive.com/x/pittsburghtrib/s_75872.html

- Futrell, Jim. “Idlewild and Soak Zone.” Amusement Park’s of Pennsylvania. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole, 2002. 51-63.

- “Idlewild and Soak Zone - Recognition.” Spiritus-Temporis.com - Historical Events, Latest News, News Archives. 24 June 2010. <http://www.spiritus-temporis.com/idlewild-and-soak-zone/recognition.html>.

- “Idlewild Park and Ligonier Valley Rail Road Association Save Historic Landmark; Kennywood Entertainment, Richard King Mellon and Allegheny Foundations help protect Darlington Station.” PR Newswire 11 Oct. 2006. Wire Feed.

- “Idlewild Park Author to Lead Public Relations Effort.” Arcadia Publishing - Local History Books. Arcadia Publishing, 21 Apr. 2005. 22 June 2010. <http://www.arcadiapublishing.com/news_article.html?id=92>.

- Idlewild Park Three-Peats as the World’s Second Best Amusement Park for Kids; Awarded third Golden Ticket in a row by Amusement Today Magazine.” PR Newswire 30 Aug. 2006.

- “Pennsylvania: Ligonier Highland Games.” American Memory from the Library of Congress. Web. 28 June 2010. <http://lcweb2.loc.gov/diglib/legacies/PA/200002950.html>.

- Washington, George. “The Braddock Campaign.” Scribner’s Magazine XIII.5 (1893): 537.

- Welcome to Idlewild and SoakZone. Web. 8 June 2010. <http://idlewild.com/>.