A simple trail through the woods on the left is all that can be seen from the parking lot. Just a quarter of a mile down the winding footpath, however, the trees suddenly open to reveal a Bucks County treasure – a seven-acre field of nothing but boulders. Located in the same county where General George Washington embarked on his famed Delaware River crossing, this geologic formation appears to defy science and reason. Seekers of the eerie and mysterious travel to this location to experience a peculiar quality that these rocks possess – they “ring” like bells when struck with a hammer. It is this phenomenon that has scientists baffled.

Ringing Rocks Park, situated near the small Delaware River community of Upper Black Eddy, contains the largest boulder field in Pennsylvania that possesses this “ringing” quality. Although the park is approximately 128 acres in size and densely covered in woods, the seven-acre section of boulders piled ten feet high is the primary attraction for visitors who arrive at the park armed with hammers. The park also boasts Bucks County’s largest waterfall, various picnic facilities, and endless displays of wildflowers.

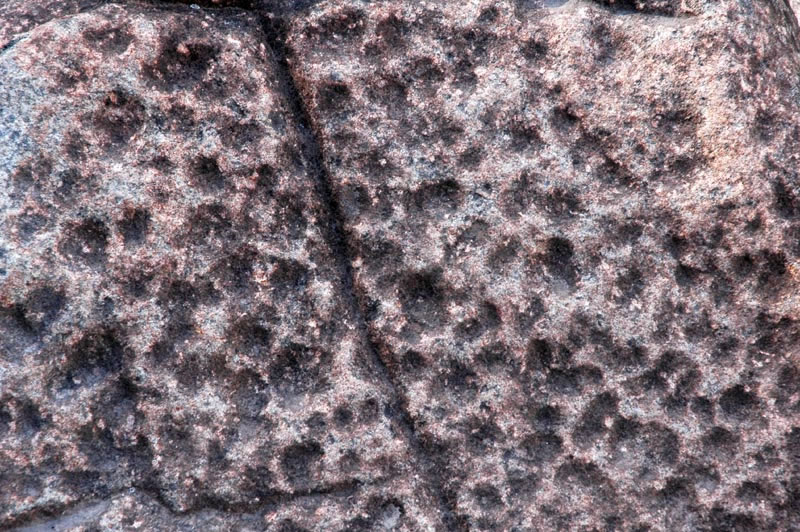

Despite these other attractions, the visual of countless boulders in varying shapes and sizes has the capacity to mesmerize. Scientist Nick Reiter describes the opening of the trees as a “sunlit scene that would, indeed, remind one of the Led Zeppelin album cover for Houses of the Holy.” Beyond the visual, however, resides the true mystique surrounding the boulder field. Native American stories passed through the generations to the first White settlers in the mid-1700s suggest that the field possesses an eerie aura. Animals were said to have steered clear of the rocks, and plant life was described as being completely absent from the surface. The seemingly cursed nature of the boulder field was only further supported by claims of the rocks’ “ringing” properties.

Today, these descriptions bear a close resemblance to reality. According to authors and explorers Matt Lake, Mark Moran, and Mark Sceurman, not only do the rocks “resound with a clear tone, like that of a blacksmith’s anvil,” they also appear to lack any evidence of substantial plant and animal life. Furthermore, while some rocks emit a hollow bell-like sound when struck with a hammer or rock, the other two-thirds of the rocks make no such sound at all, simply emitting a dull thud. This inconsistency perplexes scientists, especially since the “live” rocks are virtually indistinguishable from the “dead” ones. Additionally, although most boulder fields are the product of a mountainside collapse and reside at the bottom of a hill, this boulder field rests at the top of a hill. Without any indicators that a glacier could have formed the field, Ringing Rocks Park’s formation is another topic shrouded in mystery.

Scientific investigation concludes that these particular rocks may have taken over 175 million years to form. Ringing Rocks Park’s boulders are primarily composed of a substance similar to volcanic basalt called diabase, which is the main component of the earth’s crust. Doctor and photographer David Hanauer asserts that the park’s composition makes it one of the eastern United States’ largest diabase fields. Because the boulders have a high diabase content, they contain a healthy amount of aluminum and iron, which sometimes appears as veins of brown and red throughout the rock.

Science suggests that approximately 12,000 years ago, near the end of the Pleistocene Epoch, the boulders of Ringing Rocks Park split apart and experienced a series of freezing and thawing cycles. Hanauer points out that this process, specifically recognized as “frost wedging,” lasted for many years and produced numerous small, broken pieces of diabase. These separate pieces then underwent “solifluction,” a process in which saturated sediment, such as the soil underneath the boulders, slowly shifts downhill over an impermeable surface, carrying the contents above it. Some scientists claim that the underlying ground over which this saturated soil traveled was mostly permafrost, or permanently frozen earth. The downhill shift over permafrost, which most likely occurred during previous ice ages in the example of Ringing Rocks, is known as “gelifluction” and is very similar to solifluction. This movement of soil most likely carried the boulders to their current location and explains why they have accumulated in such a concentrated area. However, this is only a theory proposed by science, not a concrete account.

Skeptics have more intriguing explanations behind the formation’s origin. Radioactivity and the impact of meteorites have been suggested as well as the influence of mysterious magnetic fields. Seekers of the paranormal even suggest Native American curses hang over the boulder field and cause compasses to malfunction. Writer and zoologist Ivan T. Sanderson, after observing the uncanny nature of the “ringing” and the lack of wildlife throughout the field, commented in 1967, “something was not right here…”

The true splendor of the boulders of Ringing Rocks did not emerge until the late nineteenth century when a Bucks County local, Dr. J. J. Ott, ventured to create music with the rocks’ acoustic qualities. After collecting specific rocks that possessed varying pitches, Dr. Ott arranged a concert in 1890 for the Buckwampum Historical Society of Bucks County. Accompanied by the Pleasant Valley Band, a brass ensemble, Dr. Ott performed various selections using the rocks. In an article entitled “Rock Music” for Natural History magazine, John Gibbons and Steven Schlossman portray Ott’s performance as possibly the first ever “rock” concert.

Inspired by history, local musicians have recently followed in Dr. Ott’s footsteps and performed their own private concerts on the rocks. Assorted instruments such as hammers, sticks, and even railroad spikes are popular means to create this “rock” music.

Why do these rocks “ring” after all? The proposed properties that lead to this phenomenon are manifold and hotly disputed. The first scientist to seriously investigate the sound qualities of these unusual boulders was geologist Richard Faas of Lafayette College in 1965. In his laboratory Faas tested the rocks’ acoustics by striking their surfaces to emit their unique tones. However, most rocks created tones that were well below the audible frequencies of the human ear. Faas determined that what made certain rocks produce a noticeable frequency was the interaction of various tones together from within the same rock. Faas was never able to pinpoint, however, the actual physical aspect of the rocks that produced these sounds.

Researchers and scientists have proposed a number of explanations that help clarify which physical properties of the rocks may be the source of the ringing. Author Marcia Bonta asserts that scientists have come to agree “that the phenomenon is caused by high amounts of iron within the rocks.” When the rock is struck, the iron and hard mineral contents create ringing sound waves. Bonta further states that the rocks that do not ring either lack sufficient amounts of iron or are wedged too tightly between other rocks.

Other scientists support the idea that the sounds are a product of differing stress levels within the rocks. Scientists from the Physical Geography Department of Aristotle University, Greece, and the Department of Geological and Geophysical Sciences of Princeton University claim that the boulders ring “because the unweathered slabs of coarse-grained diabase are supported at a few points by other blocks in an open fabric.” These researchers suggest that the layering of the boulders contributes to their sound. However, this explanation does not justify why individual rocks still ring in the laboratory when taken from their natural location.

Scientist Nick Reiter, after conducting his own experiments at the boulder field, agrees with the majority of proposed reasons. He elaborates, though, that no single explanation can be held as the ultimate rationale. Reiter notes that the rocks are not hollow, they are not magnetic, and they rest at points on other boulders. Furthermore, he discovered that the size of the boulder does not show a direct relationship to the frequency emitted. Reiter’s most important finding, however, is that while only one-third of the rocks ring, their internal and external appearances do not “show any visible difference in color, grain size, or texture between ringers and non-ringers.”

Although many theories exist to help shed light on the science behind Ringing Rocks, no definitive conclusion has been reached, leaving a cloud of mystery over the park. Researchers still cannot explain why none of the rocks in the adjoining forest produce any such ringing sound.

Why plant and animal life seems to avoid the surface of the boulder field is another perplexing anomaly. Perhaps the warm rays of the sun create a surface temperature that is too hot to handle. Additionally, the ten-foot depth of the boulder field does not provide a hospitable environment for plant life to grow. Nonetheless, Reiter noticed on his trip to Ringing Rocks that absolutely no birds flew over the field. He saw no evidence of bird droppings and very little lichen growth, an observation that “struck [him] as peculiar.”

Ringing Rocks Park is a destination for scientists, thrill-seekers, and families. Multitudes of tourists visit the boulder field to expand their scientific knowledge or to learn about geology. Others arrive at the park prepared to study the paranormal and supernatural. However, most visitors flock to the boulder field to experience the pure joy of hitting a hammer against an endless collection of “musical” rocks. In fact, the image of children and adults running around with hammers in hand is quite unique. The rich history and rare musical quality contained in these boulders makes Ringing Rocks Park a timeless destination for Bucks County sightseers. “If you turn off your analytical mind long enough,” say authors Matt Lake, Mark Moran, and Mark Sceurman, “you start to feel the fear of an ancient and mysterious place surrounding you. Then some kids will bang a tune out of stone, and you’ll forget all about that fear.”

The Center wishes to thank David Hanauer for his assistance in illustrating this article.

Sources:

- Bonta, Marcia. Outbound Journeys in Pennsylvania. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1987. 47-49.

- Hanauer, David. "Ringing Rocks." David's Photographic Tour of Bucks County, Pennsylvania. N.p., June 2004. 24 Sept. 2010. <http://www.davidhanauer.com/buckscounty/ringingrocks/>.

- Krystek, Lee. "Weird Geology: Ringing Rocks." The Museum of Unnatural Mystery. N.p., 2001. 26 Sept. 2010. <http://www.unmuseum.org/ringrock.htm>.

- Psilovikos, A, and F. B. Van Houten. "Ringing Rocks Barren Field, East-Central Pennsylvania." Sedimentary Geology 32.3 (1982): 233-43.

- Reiter, Nick A. "The Ringing Rocks of Pennsylvania: A Musical Mystery along the Delaware." The Avalon Foundation: Paranormal Investigation and Research. The Avalon Foundation, 17 Aug. 2006. 28 Sept. 2010. <http://www.theavalonfoundation.org/docs/rrocks.html>.

- Sceurman, Mark, Mark Moran, and Matt Lake. Weird Pennsylvania: Your Travel Guide to Pennsylvania's Local Legends and Best Kept Secrets. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2005. 48-50.