Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA

Of the various attempts in history that were made to solve the so-called "Indian problem" (relocation and extermination primary among them), an attempt at forced assimilation was made using education in the late 19th century. After the Civil War and Indian wars, most Native Americans were confined to reservations, reduced to a helpless state, and the American government knew little of what to do about the Indians' future status. Historian Francis Parkman once wrote in 1851 that "the aborigine was by nature unchangeable and by fate doomed to extinction."

A Civil War veteran named Richard Henry Pratt believed that the Indians could become a contributing part of the population through education. He started the system of Native American boarding schools as an effort to follow through with his advocating efforts of "assimilating the red man through total immersion." Pratt's goal of "assimilation" was to systematically strip away any trace of tribal culture and to train them to become "useful" in American industrial society. "Transfer the savage-born infant to the surroundings of civilization and he will grow to possess a civilized language and habit" he wrote; more succinctly put, "Kill the Indian, Save the Man." His philosophy brought about the Carlisle Indian School, the first off-reservation boarding school, once located in Carlisle, Cumberland County.

Archives and Special Collections,

Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA

In 1875, Pratt was assigned to guard a group of the most "hostile" prisoners from the Caddo, Southern Cheyenne, Comanche and Kiowa tribes at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida. He selected a group of 17 of these prisoners to test his theory about assimilating them into white society through Indian education and he sent them to the Hampton Institute in Virginia, which was then a boarding school for black children. The prisoners adapted completely to European-American ways which encouraged Pratt to open an all-Indian boarding school of his own.

In 1879, Captain Pratt convinced the Bureau of Indian Affairs to open the Carlisle Indian School in a small, rural town of Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He then traveled West to the Dakota Territory to recruit students by persuading tribal elders and Chiefs that the reason the washichu (Lakota word for "white man") were able to take their land was because the Indians were uneducated. Because of Pratt's arguments, many of the first children to be sent to Carlisle were sent voluntarily by tribal families with hope of having them educated. Descendants of famed chiefs Spotted Tail and Red Cloud were among the first sent to Carlisle School.

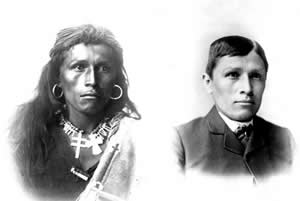

In anticipation of the first wave of students, Pratt hired a full complement of handpicked staff, for both academic and industrial instruction. One of the staff's first responsibilities was to hire a barber to cut the children's long hair. For the Lakota, the cutting of hair was symbolic of mourning and there was much wailing and mourning which lasted into the night. "In our culture, the only time we cut hair is when we are in mourning or when someone has died in the immediate family. We do this to show we are mourning the loss of a loved one," said Sterling Hollow Horn, a descendant of Carlisle students. After replacing Indian dress with military uniforms for the boys and Victorian style dresses for the girls, the Indians' physical appearance was transformed. Pratt even hired photographers to illustrate the before and after "contrast" photos of the students which were then sent to officials in Washington to prove that the school was in good order.

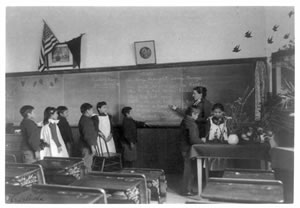

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was a formalized and well-structured institution that spent a half-day on academic classes and the other half learning various in trades. Classes included subjects such as English, math, history, drawing and composition. Carpentry, tinsmithing, blacksmithing were common trades for the boys, and cooking, sewing, laundry, baking, were common trades for the girls. Music was also a part of the program with many students who studying how to play instruments.

Heard Exhibition

Although the Carlisle Indian School taught the students the trades of "western culture," many critics still disagreed with the structure and the aim of the Indian boarding schools at the time. One of Carlisle's harshest critics was Gertude Bonnin, (Zitkala-Sa), a famous Indian author and artist who once taught at the Carlisle Indian School. She believed that Indian students were capable of and should be exposed to higher learning and academic subjects, and should not be limited to vocational training. She also disapproved of the military discipline and Christian evangelizing the school imposed on its students. According to Zitkala-Sa, the boarding school system was a "miserable state of cultural dislocation," that created problems long after the children returned home.

Pratt's initial motives of educating the Indians might have been noble, but his methods could be quite harsh. Military style discipline was strictly enforced with regular drill practices and the children were expected to march to their classes, and from the classes, to the dining hall for meals. Beatings were a common form of punishment for students' grieving behaviors, speaking their native languages, failure to understand English, or attempting to escape and violating the harsh military rules. According to Dr. Eulynda J. Toledo of the Boarding School Healing Project, children at Carlisle had their mouths washed with lye soap for speaking in any language other than English. If the children broke any rules their punishment was determined by an organized justice system of their peers.

Other forms of punishment included being set to hard labor and confinement to the guardhouse. Built in 1777 by Hessian prisoners during the Revolutionary War, the guardhouse contained four cells in which children were locked, sometimes for up to a week. It still stands as a haunting reminder of the school's rigidity.

The children at the Carlisle Indian school had extremely difficult times adjusting to their new living conditions. The health of many Indian students was in peril after European contact due to the lack of natural immunity. Food was scarce and of poor quality. Illness and death among the children were common. Many of the children suffered from separation anxiety, smallpox and tuberculosis which at that time quickly resulted in death because of the lack of medical treatment. While most of the children were sent back to their reservations, hundreds of others passed away at the school. A hundred and ninety two children died and were buried in the school cemetery, a majority of whom were buried from the Apache tribe.

The Carlisle Industrial School did, however, provide many programs to benefit the Indian children. One particular program was the "Outing System" where students were sent out to different towns and live with white families to learn how they lived. Pratt referred to the "Outing System" as "The Supreme Americanizer." It provided a means through which students could obtain special training in skilled occupations which eventually would lead to profitable employment. During the first summer of the school, Pratt found places at individual homes, including homes of Quaker families in eastern Pennsylvania and local businesses for twenty-four students. The students were paid for their services and the money earned was deposited in an interest-bearing bank account by the school, and then given to the student when he or she graduated. The second year, the program grew to 109 students. The Outing System succeeded in placing the Indian children closer to the culture they were to absorb and continued throughout the school's thirty-nine years of existence.

Throughout Pratt's twenty-five years of supervision, he often conflicted with government officials over his outspoken views on the need for Native Americans to become absorbed into Euro-American society. He was against the reservation concept and continued to fight with the Indian Bureau. Pratt was eventually relieved as Superintendent of the Carlisle Indian School in 1904 and soon his strict disciplinary ideals for the school were relaxed.

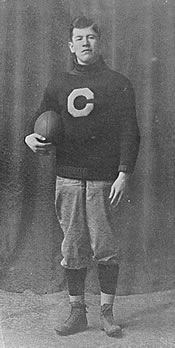

Pratt's successor, Captain William A. Mercer, bought changes to the school in an effort to appease the Indian Bureau. A diminution of the military style industrial and academic programs took place and an increased emphasis on athletics was enforced. The Outing System and the school's athletic program were recognizably the two of the best supported and recognized programs during the school's history. The new emphasis on athletics helped pave the way the arrival of a particular famous individual Jim Thorpe, eventually hailed the world's greatest athlete. Thorpe, having a mother from the Sac tribe who originally named him Bright Path, began his athletic career at Carlisle Indian School in 1904 playing football and running track. He led the Carlisle football team that bought the school nationwide attention. Later on in his career, Thorpe played six years of professional baseball as an outfielder for the Cincinnati Reds and the Boston Braves and even holds the decathlon record winning six of ten events at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics.

Till this day, the Carlisle Indian School and the ideas of "assimilation" are very controversial. Pratt may be considered dogmatic by today's standards, but his views of Indians' education were considered necessary, and even enlightened, 100 years ago. He and most people who regarded themselves as advocates for Native American education considered Carlisle a "noble experiment." Most students at Carlisle, however, found themselves an alien in both worlds after returning home to their reservations. They were too white for the Indians and too Indian for the whites.

Information concerning the Carlisle Indian School can be found at the Cumberland County Historical Society home to the most extensive collection of archival materials and photographs from the Carlisle Indian School. It is located in the heart of Carlisle, Pennsylvania the lives and identities of thousands of Indian children were once totally transformed. Whatever the outcome, Pratt's efforts at the Carlisle Indian School mark a significant chapter in the history of education in the United States and of its native peoples.

Dickinson College's Archives and Special Collections have created an extensive online gallery of pictures of the Carlisle school in a Flickr photostream. Click here to go directly to that photostream.

Sources:

- Adams, David W. Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875 - 1928. Lawrence: UP of Kansas, 1995.

- Brunhouse, Robert L. "The Founding of the Carlisle Indian School." Pennsylvania History 6.2 (April 1939): 72-85.

- Gansworth, Howard. "First Days at the Carlisle Indian School: An Annotated Manuscript" Ed. Todd Leahy and Nathan Wilson. Pennsylvania History 71.4 (October 1, 2004): 479-494.

- Witmar, Linda F. The Indian Industrial School, Carlisle, Pennsylvania, 1879-1918. Harrisburg, PA: Huggins Printing Company, 1993.