In the middle of winter, walking through the streets of Eckley, the eerie silence weighs heavy upon the air. The crunching of dirty, gray snow underfoot is by far the loudest sound. The abandoned houses, in alternating states of remodeling and disrepair lean to one side or another, and the small sheds and outhouses lack doors or roofs. The town has just a single street that stretches far into the distance, with houses and company buildings lined up on each side. The road through the town may now be paved, but it is in dire need of repair. Only forest lies beyond the wooden houses, and it is easy to believe that no one lives anywhere near this old and forgotten town. The dirt and slush mix together to muddy shoes and the creaking of the dilapidated buildings grows stronger as the wind picks up. Without a doubt, Eckley looks and sounds like a ghost town. However, after ascending the first small hill, the illusion breaks. A brand new Prius sits parked next to one of those old buildings and a kindly looking man waves to greet visitors.

Contrary to its initial appearance, Eckley houses about a dozen full time residents, descendants of the miners that at one time lived in the village. “I’ve lived in Washington, and other cities, and I came back to Eckley, so that tells you something” says George Gera, a current village resident. Residents like Gera are all that remain of this once thriving mining community that lives on as an tangible piece of Pennsylvania’s history.

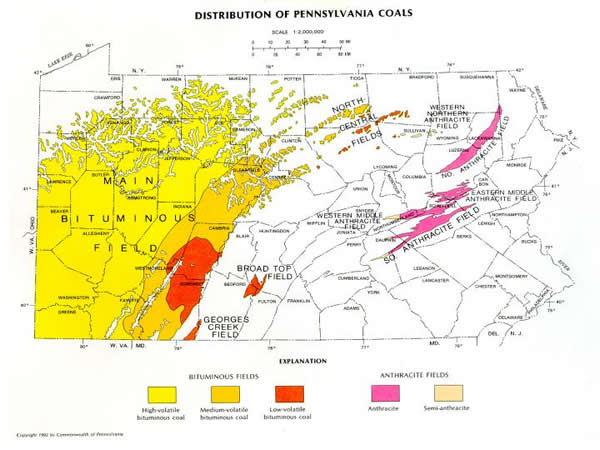

Eckley Miners’ Village, like many small mining towns in Luzerne, Carbon and Schuylkill counties, grew from the interest in mining anthracite coal. In 1853, prospectors first stumbled across a tiny and mostly self-sufficient village in what would later become Luzerne County. The people of this village, at that time called Shingleton, farmed and produced wooden shingles which they traded for technology and luxuries in nearby larger villages. Below and around this village, large coal deposits promised the chance for profits for the prospectors and their associates and they quickly became interested in this isolated area.

Richard Sharpe, a coal contractor, Francis Weiss, a surveyor, and Judge John Leisenring banded together to form Sharpe, Leisenring and Company, and wasted no time to attempting to secure rights to the land so that they could commence operations. Their main obstacle in this task was Judge Charles S. Coxe, the executor for the Tench Coxe Estate and son of Tench Coxe, a political economist, assistant secretary of the treasury under George Washington and prominent Philadelphian. As the land owner of substantial portions of northeastern Pennsylvania, Charles Coxe was well aware of the value of the land that his father had invested in. By 1854, Sharpe, Weiss and Leisenring, joined by Lansford Foster, a merchant, had negotiated a lease for the fifteen hundred acre plot from Coxe and the rights to mine and transport coal from those grounds.

Within the year, construction of the coal mines at Shingleton had begun. The urgency for the purchase of the rights and building of the colliery (the coal mine breaker and associated buildings, including houses for the miners and engineers) is typical of the era, and common to most of the entrepreneurial companies hoping to capitalize on the rising value of coal.

Since 1833, the year that saw the invention of the hot blast furnace, coal quickly gained popularity and value as a heating and fueling source. Not all coal is equal however, and some varieties obviously had much greater merit for home heating or industrial applications, the top uses for coal in the 19th century. Coal comes in multiple grades depending on its hardness and energy density. One common way to classify coal is by percentage of volatiles, or substances trapped in the coal that lead to easier ignition. Increased concentration of volatiles also decreases the overall energy density of the coal. As a result, coal with a low percentage of volatiles has the highest amount of energy per pound and tends to have a lower risk of accidental ignition. Additionally, a low quantity of volatiles causes the coal to give off less smoke when burned.

Organized from lowest to highest percentage of volatiles, the main types of coal are: Anthracite, Steam, Bituminous, Lignite, and Peat. As a home heating source, Anthracite quickly proved to be the most effective. Anthracite can be identified by its shiny black appearance and smooth hard texture that does not rub off on the hand when touched. For prospectors in the 19th century, the specific physical appearance and texture of anthracite made it easy to identify, and the occasional surfacing of coal veins enabled identification without any preliminary digging. This ease of identification, along with the rising value of Anthracite coal led Sharpe, Leisenring and Company to quickly and confidently establish the new mining town at Shingleton.

The town that rose up at Shingleton resembled many of the other towns that had recently grown in the area. The mining towns of northeastern Pennsylvania had many characteristics in common and were referred to as “shanty” towns for the cheapness of their dwellings and the low quality construction. In Eckley, Sharpe, Leisenring and Company continued to expand its operations and quickly started to require on site housing for its employees and laborers. The housing was divided into four clearly demarcated regions to separate workers and supervisors based on their level of prestige within the company. Keith Parrish, a tour guide at the Historical Anthracite Museum in Eckley, notes that “the farther down the town we go, the richer the people.”

At the entrance to the town lie the houses for the lowest classes: laborers, second-class miners, and their families. These shacks provided cramped and bare-bones living for the large majority of people in Eckley. Serious skimping on construction materials was evident on these, with construction completely done in wood and lacking any insulation. The builders painted the houses in black and red, because they were the two cheapest colors of paint at the time. Karl Zimmermann describes the insides of the houses as decorated with sparse “rudimentary, makeshift furnishings.” The exhibits at the Eckley Anthracite Museum further elaborate on this, describing the newspaper used as insulation and flooring, mixed with mud or dirt, depending on the weather. In the winter, cold air easily found its way through the open board walls and floor, and in the summer the heat was inescapable. The lack of individual plumbing meant that outhouses were commonplace and water had to be retrieved from communal wells and, later, water mains.

Further down the street the houses of the miners and contractors stood, barely an improvement over the rickety houses of the lowest class but housing fewer families. At least in these dwellings a family’s four rooms were not additionally sublet to others in order to minimize costs. Like the houses for the lower social tier, the employees were almost entirely responsible to provide their own furniture and amenities. To some extent the rent they paid to the company barely got them anything other than a roof over their heads and the right to work for the company.

The next group of dwellings was for upper supervisors and engineers. These houses generally stood alone and contained plenty of space, though their construction differed little from the earlier houses. Notably, the renters of these houses could afford higher quality furnishings and proper insulation.

In the open area beyond the majority of dwellings rested Richard Sharpe’s elaborate gothic revival style house, by far the largest building on site. In the 1800’s the area around Sharpe’s mansion would have had the only pleasant recreational area nearby. Most likely grass and trees were properly maintained against the coal dust and dirt that covered the rest of the town.

Miners and their families in Eckley lived harsh and difficult lives, but often, this was an improvement over their previous condition in either their home country or another part of the United States. In Eckley, they had a steady job and home, even if both of those were less than desirable. The wages paid at Eckley were often superior to those gained in other uneducated professions, and while the company certainly did not coddle its employees, the conditions provided were superior to other “patches,” small mining towns, in the area.

Miners and laborers saved money and expanded their families, letting some of their sons and daughters escape the drudgery of the mines by providing better education. However, many families, especially those that worked as laborers, simply did not have money to spare for those things. Their sons had no choice but to work in the mine or associated buildings. The most common job for young boys was as “breaker boys” who, as Fred Lauver puts it, were in charge of “sitting astride breaker chutes through which the coal roared, and picking out slate and other debris by hand.” These boys were paid a fraction of that paid to their parents and worked from ages as young as eight. Many stories circulated of boys who had been injured by the rushing coal and slate, and stories of boys falling into the chutes were not only very common but also probably true. According to Lauver, in 1900, one sixth of the personnel in anthracite mines were boys below age 20, and even after the first child labor laws were passed, the number of boys employed this way failed to change significantly.

For the fathers of these boys, the conditions were hardly any better. Mine work had extremely long shifts of up to 16 hours and most of that was spent underground. Mine collapses and poisonous or explosive pockets of gas were common killers, and the coal dust that miners continuously inhaled lowered their lifetimes significantly by causing considerable lung damage. This affliction, called “black lung,” was common among all of the mining patches in the area and was considered an unfortunate, but expected hazard of mining. However, the money was completely worth the risks for the miners in Eckley, and there was never a shortage of people to replace those that died to the dangers of mining anthracite.

Over the course of the town’s existence, prospects were not always as rosy as the founders originally expected when founding the town. Tony Wesolowsky mentions that around 1860 “the high cost of transportation, poor markets, and meager profits” hounded the company. Along with lengthy and unproductive winters, the future of the town of Eckley often looked grim. In 1861, however, the steamboat trade “breathed new life into Sharpe, Weiss and Company” and the Civil War produced an enormous demand for a clean burning fuel. These events caused a threefold increase in coals selling price, from $2.10 to $6.25 a ton, according to Wesolowsky. While the productivity and viability of the town wavered over the years, it wasn’t until the 1920s that the town truly began to fade in importance.

New advancements in mining technology, including the steam shovel and strip mining, reduced the need for large numbers of miners. By 1920, the population of Eckley was about a third of its 1870 levels, and the Coxe estate leased the mining town to a series of coal companies. By the 1950s and 1960s, the anthracite industry had mostly subsided to a minor level, with coal being mined only for legacy operations and some household use. After all, the conveniences of oil, natural gas, and, most importantly, electricity pushed anthracite out as a viable source of energy and heat.

The town of Eckley continues to stand due to two separate efforts that maintained interest in the town. In 1968, Paramount Pictures leased the town for one year in order to film the film The Molly Maguires, a story about the organization in Ireland and northeastern Pennsylvania dedicated to vigilante activities and fighting mine owners for better living conditions and pay. For this movie, Paramount added a number of buildings to recreate the feel of an active mining town, including a three-quarters scale coal breaker. Additionally, a new company store was added and a number of buildings were covered with boards to imitate the appearance of old coal mining towns. Many of these changes persist today, though quite a few have been replaced by more modern refurbishing. While the movie was a moderate success, the true benefit of the filming was the attention it drew to the town of Eckley.

Vance Packard mentions that the filming of the movie simply brought more attention to the town. “Some people became so enthused by the whole filming of the movie that they began to look at Eckley - and perhaps their general culture - in a different way,” Packard mentions in an interview quoted by Lauver.

The coal mining culture that had always existed in the town and its remaining residents was noticed by a number of people that subsequently banded together to preserve the town as a historical site. As such a prominent and suddenly good looking example of anthracite mining history in Pennsylvania, Eckley was further designated as the future site of the Pennsylvania Historical Anthracite Museum. Today, Eckley Miners’ Village is open to the general public and continues to house the remaining descendants of the town’s miners. In a region in which there were once dozens of small mining villages, only one remains. However, this village, Eckley Miners’ Village, and all of its rich history, truly serves as a window into the past.

Sources:

- Aurand, Harold W. Coalcracker History: Work and Values in Pennsylvania Anthracite. London: Associated University Presses, 2003.

- Blatz, Perry K. Eckley Miners’ Village: Pennsylvania Trail of History Guide. Harrisburg: Stackpole Books, 2003.

- Fey, Arthur W. Buried Black Treasure: the Story of Pennsylvania Anthracite. Bethlehem, 1954.

- Lauver, Fred J. “Visiting the Museum of Anthracite Mining: A Walk through the Rise and Fall of Anthracite Might.” Pennsylvania Heritage 27.1 (2001): 32-39.

- Parrish, Keith. Pennsylvania Anthracite Heritage Museum. Eckley Miners’ Village. Personal Interview. 14 Mar. 2010.

- Richards, John S. Early Coal Mining in the Anthracite Region. Charleston: Arcadia, 2002.

- Wesolowsky, Tony. “A Jewel In the Crown of Old King Coal: Eckley Miners’ Village.” Pennsylvania Heritage 22.1 (1996): 30-37.