Positioned on the muddy west bank of the Delaware River, a historic structure still stands after more than 250 years. Located on Mud Island, just outside Philadelphia, Fort Mifflin has played a role in almost every war the United States has fought since the Revolution. Fort Mifflin was of great importance to George Washington and the Continental Army when the fort delayed British troops from proceeding down the frigid Delaware River in the cold month of November 1777. This allowed Washington and his army to relocate and reassemble at Valley Forge, a key moment in the development of this fledging army. Later in the war the fort suffered the biggest bombardment the North American continent has ever witnessed, yet it remains intact and accessible to this day. Despite a long and rich history as Philadelphia’s, and the nation’s, protector, Fort Mifflin remains one of the largely unknown and unacknowledged military sites in the United States.

Although Fort Mifflin was not constructed until 1771, plans for a fort on the Delaware to provide security began to unfold in 1626. The Swedish, Dutch and British all fortified the Delaware River from 1626 to 1774 and found a key defense point where the Delaware converged with the Schuylkill River near Mud Island. In 1626, the Dutch built Fort Nassau on the east bank of the Delaware River, which allowed them to exploit fur trade in the region. The Dutch controlled the Delaware with multiple forts until the 1660s. When the British took over the Delaware, the Dutch were forced to leave.

Fort Mifflin was built by the British in 1771 to strengthen the colony’s control over the Delaware River. Construction stopped after the south side wall was finished in 1773. In 1776, when the American colonies separated from England, the Americans continued construction of the fort in order to prevent the British from sailing ships to Philadelphia, the nation’s capital at the time. Washington relied on the Pennsylvania Navy to guard Fort Mifflin and nearby Fort Mercer from the British. He had such faith in this operation that he reportedly told Navy Commodore John Hazelwood, “I have not the least doubt but we shall by our operations by land and water oblige the enemy to abandon Philadelphia.”

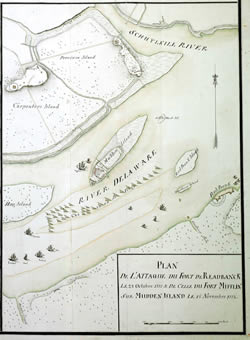

The British finally bombarded Fort Mifflin 7:30 a.m. on November 10, 1777. Captain Montresor of the British Army wrote after the attack, “We opened our Batteries against Mud Island Fort, the whole consisting of two 32-pounders, six 24-pounders Iron, one 18-pounder, two 8-inch Howitzers, two 8-inch mortars, and one 13-inch mortar for throwing round shot and car-cases.” For five long, brutal days, two thousand British troops and 250 ships shot over 10,000 cannon shells at the fort, trying to destroy it. Along with the Naval attack came a British Army assault with artillery guns from Providence and Carpenter’s islands, just five hundred yards away.

At the beginning of the bombardment, Fort Mifflin’s commander, Colonel Samuel Smith of Maryland, was urged by Washington to hold the fort “to the last extremity.” Cannonballs rained over the fort and the American soldiers inside it. The four hundred continental soldiers in the fort were greatly outnumbered and lacked the equipment to retaliate against the dual assaults from the British Navy and Army. The British first took out the northwest wall cannons of the fort, then destroyed the west stone wall of the fort. British cannons eventually destroyed twenty sections of Fort Mifflin’s palisade. Mortars landed on the cedar roofs of the barracks and blockhouses, setting the fort on fire despite the constant rain and efforts to extinguish the flames.

Without the fort’s main cannons, the soldiers could not resist the British. Soldiers at Fort Mifflin held the British for as long as possible, but after five days and the death of 150 soldiers, the Continental Army was forced to abandon the fort on November 15, 1777. This heroic defense inspired one of the United States founding fathers, Thomas Paine, to write, “The garrison, with scarce anything to cover them but their bravery, survived in the midst of the mud, shot & shells, and were obliged to give up more to the powers of time & gunpowder than to military superiority.”

After the British bombardment, Fort Mifflin was left in ruins until 1793 when the planner of Washington D.C., Pierre Charles L’Enfant, began reconstruction of the now historical landmark. In February 1795 L’Enfant was replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Stephen Rochefontaine when L’Enfant proved too difficult and expensive to work with. Rochefontaine completed the construction of Fort Mifflin in 1799, marking the end of the most expensive expenditure for fortifying ports and harbors of the past five years. The Department of War had spent over $100,000 dollars on fortifying Fort Mifflin, while only $30,000 was spent on Charleston, the next largest expenditure.

Secretary of State Alexander Hamilton had big plans for the fort and wanted to expand and solidify its defenses before Thomas Jefferson was elected president in 1800. Hamilton believed that Fort Mifflin was the most strategic military base and pushed for development, no matter the cost. After Jefferson was elected, he decreased the funding from $15,000 dollars in the year of 1800, to $1,000 dollars in 1801. Since the nation’s capital had moved from Philadelphia to Washington D.C. the year before, officials no longer saw the importance of Fort Mifflin.

As a precautionary protection measure for Philadelphia in the War of 1812, Fort Mifflin was once again actively manned. Captain James Nelson Barker was appointed commander of the fort on July 16, 1812. Although the fort was prepared to defend Philadelphia, it saw no action during the War of 1812. The fort remained abandoned after the war’s end, until Congress granted more than $70,000 dollars between 1835 and 1839 for repairs. An additional $15,000 dollars was provided for removal of a sandbar in front of the fort. Although the U.S. Army abandoned the fort in 1853, the U.S. Navy began using it for the storage of cannon shells and gun powder two years later.

During the spring of 1861, several local volunteer units manned Fort Mifflin in order to defend Philadelphia from Confederate invasion. By the end of the Civil War, Fort Mifflin had not shot one cannon at the enemy, but instead served as prison for Confederate and Union solders beginning in July 1963. Fort Mifflin held Confederate soldiers captured at the Battle of Gettysburg, Union draft dodgers, and Union military criminals. In 1864, 70 percent of the prisoners held at Fort Mifflin were civilians, and only half were draft dodgers.

Though President Abraham Lincoln often discouraged the death penalty, he wanted to make an example of Private William Howe, a wanted killer and deserter from the Union Army. Howe was hanged at Fort Mifflin in front of the other deserters on August 26, 1864, to show that Lincoln and the Union Army would not tolerate cowards.

After the Civil War, the military only used Fort Mifflin as an ammunition depot in WWI and WWII. In 1954, the fort was closed and no longer used as a military post. When Fort Mifflin closed, it was the oldest fort in continuous use in the United States, having served from 1771 to 1954.

Fort Mifflin’s history following WWII was a fifty-year struggle over historic preservation. Today, it has been restored to its 1834 appearance and is open to the public from Wednesday through Sunday, year round. The fort offers daily weapons demonstrations and still has 14 authentic restored buildings, which include casemates, the Northeast Bastion, the arsenal, various batteries, soldiers’ barracks, officer’s quarters, and a blacksmith shop. All of these buildings can be explored by the public through self-guided or organized tours. The fort hosts many different activities throughout the year, including Fourth of July fireworks, birthday parties, Boy Scout overnight trips, and multiple reenactments of the battle that saved Washington and his troops in the Revolutionary War.

Recently, Fort Mifflin has had visitors searching for ghosts. Many people have heard and claimed to see “The Screaming Lady” Elizabeth Pratt and “The Man Without a Face” William Howe. Elizabeth Pratt lived with her husband and daughter in the officer quarters at Fort Mifflin. Her daughter fell in love with an enlisted man, causing her husband to disown her daughter and never reconcile with her. After the death of her daughter due to typhoid fever, Elizabeth Pratt hanged herself from the balcony. It is said that visitors of the fort still hear Elizabeth’s desperate screaming at night in the officer quarters. Howe, hung as a deserter at Fort Mifflin during the Civil War, has been reported to be seen, with no face, sewing in casement 5. This paranormal activity has caused shows like Ghost Hunters and Ghost Hunters Academy to visit the fort and investigate the sightings.

Fort Mifflin has had many different roles in the security of the United States over its 175 years of service. Although Fort Mifflin is most prominently known for its delay of the British Navy on the Delaware in the Revolutionary War, it has also served as a garrison in the War of 1812, a Confederate prison during the Civil War, and an ammunition depot in the first and second World Wars. Although the fort only saw action once in November 1777, it has remained an unflagging, and often unacknowledged, protector of its country’s interests.

Sources:

- Alotta, Robert I. Old Fort Mifflin: The Defenders. Philadelphia: Shackamaxon Society, 1973.

- Dorwart, Jeffery M. Fort Mifflin of Philadelphia: An Illustrated History. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998.

- Jackson, John, “Fort Mifflin: Valiant Defender of the Delaware.” Norristown, PA: James & Sons, 1986.

- Laumark, Sandra and Barbara Liggett. “The Counter fort at Fort Mifflin.” Association for Preservation Technology International, 1979.

- Sharp, David. “Ghost Hunters Academy’ premieres tonight and we’ve seen it.” The Birmingham News 11 Nov. 2009

- Writer, Ghost. “Most Haunted Places in America: Fort Mifflin.” Ghost Eyes. 7 Aug. 2009. 23 Nov. 2009 <http://www.ghosteyes.com/haunted-fort-mifflin-pa>.