Several dozen miles from the Pennsylvania Capitol in Harrisburg, the town of Hershey pumps sweet chocolate smells from a 2-million-square-foot manufacturing plant. Street signs with cocoa-inspired names such as Chocolate, Java and Granada mark tree-lined avenues lit by lamps shaped like Hershey Kisses. Everything in this town of about 13,000 residents seems to reflect the Hershey's Chocolate Company that spawned it. To understand how an area once was home to little more than dairy farms was transformed into the headquarters of America's largest chocolate and confectionary maker, one must understand the man behind the transformation: Milton S. Hershey.

Hershey was not born with a clear, predestined path to becoming the king of a vast chocolate empire and one of the country's richest people. He was born in a fieldstone farmhouse on September 13, 1857, near Derry Church, the small town that would eventually become Hershey, Pennsylvania. He was the only surviving child of Henry and Fanny Hershey, both descended from the Pennsylvania Dutch. The family was of Mennonite stock, and the tradition instilled the young M.S. Hershey with hard-working and frugal values that he would keep for the rest of his life.

As soon as he started his schooling at seven years old, Hershey appeared headed for a rough education. He changed schools often, attending seven different ones as his family moved throughout the region. The lack of constancy led him to finally drop out at 14 and pursue an apprenticeship instead. He first worked with the publisher of the pacifist newspaper Der Waffenlose Waechter, German for "The Unarmed Watchman." There he slowly learned that he was not cut out for the printing business. He was fired when he angrily threw the owner's hat into the printing machinery.

Hershey's mother then paid to send him to apprentice with Joseph H. Royer, a confectioner in nearby Lancaster. Hershey worked at Joe Royer's Ice Cream Parlor and Garden, a popular spot for the townspeople. He enjoyed the work much more than that at the printer, and Royer soon promoted him to candy-making duties in the kitchen.

After four years of learning the trade, the 19-year-old Hershey decided to start his own candy business. With his apprenticeship savings and $750 from his mother and aunt, he headed to Philadelphia to make his fortune. He rented a three-story building on Spring Garden Street, spending his days boiling, stretching and cutting caramel and his nights selling them for pennies. He then expanded into selling nuts and baked goods. Yet despite his efforts and constant financial help from his mother's family, Hershey could not keep his fledgling business profitable. The venture folded after six years, and he returned to Lancaster.

Successive attempts at selling his candy ended similarly. He arrived in Denver in 1882 just in time for a local depression that hampered his work. Similar travels to Chicago, New Orleans and New York City also failed. Problems pestered Hershey, ranging from unforgiving landlords to young troublemakers setting his cart on fire and sending his horse bolting. Money problems followed him, and New York police finally confiscated his candy-making equipment after he defaulted on a payment. He used his last few dollars to buy a ticket back to Lancaster and to ship his remaining things home. At 30, he was nearly bankrupt.

U.S. Postal Service

These early failures did not squash Hershey's spirits. He set out to once again raise capital for another business, but this time no relative would offer help. None trusted his track record. He finally amassed enough money from loans to rent a warehouse that once housed one of Thomas Edison's electric plants. In addition to his caramel duties, he worked on the side as a handyman and salesman in order to make ends meet, and his mother and aunt helped wrap the candy that he churned out. And finally, luck smiled on him.

An English candy importer named Decies happened to taste one of the caramels. He asked Hershey if he could sell them in England. Hershey had never thought of that before, but he knew his product was suited for export; in Denver he had learned to use fresh milk in his creations, which would stay fresh longer than others.

Business boomed for his "Crystal A" caramels. Orders poured in faster than he and the workers he hired could fill them. Only four years after arriving back in Lancaster, he was not only renting the whole building but had also built two new floors and bought adjacent properties. He soon had to build plants in other cities, including branches in New York and Chicago. All of them churned out his many caramel creations, which he gave exotic names like Lotuses, Cocoanut Ices, Icelets and Uniques. Hershey continued playing an everyday role making them despite the newfound success. He would help in the Lancaster plant, shoveling cinders into dump carts and rolling candy. The boss who would eventually become known as "Dad Hershey" needed to be personally involved, eating with his workers in the cafeteria and persuading construction workers to teach him a little of their trade.

While keeping his hand in all areas of his business, Hershey reserved the bulk of his attention for the sweets. Although chocolate became vital to production, Hershey initially used it only to coat some of his candies. In 1892, he had attended the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It was here that the future chocolate king saw and bought chocolate-making machinery from Germany. More than a hundred "novelties" were coated with that chocolate, and they became some of his best sellers. He told his cousin, "Caramels are only a fad. Chocolate is a permanent thing."

He was able to pursue this when the American Caramel Company, his chief competitor, offered $1 million — roughly $24 million today — to buy Crystal A in 1900. After the sale, he surrendered the factory, machinery, stock, formulas and trademark. However, he refused to sell his chocolate rights and the needed equipment. He rented a wing of his former factory and was soon selling his new line. "This was the best business deal I ever made, because most of my competitors became my customers," he said.

Business soon outgrew the rented wing in Lancaster, and Hershey began looking for a new place. He considered another site in Lancaster and places in Baltimore and Yonkers, New York. Eventually, he decided to forego cities entirely and picked a spot next to Spring Creek near his hometown of Derry Church. The site was near the many dairy farms that he would need, and a nearby quarry could supply building materials. The location was also relatively close to the ports of Philadelphia and New York.

Surveyors arrived in January 1903, and construction began that March. In a race with construction, M.S. Hershey tinkered with a new formula for making chocolate. Milk chocolate in particular was not popular at the time; it was a luxury good produced exclusively and in secret in Switzerland and Germany. Hershey wanted to produce it in mass quantities and make it affordable for all. He spent weeks experimenting, using powdered milk as the Swiss used and then trying cream and sugar. The heating temperature, cooking time and order of ingredients were all subject to manipulation during the many 16-hour workdays put in by Hershey and his staff. For a while it seemed as though construction might finish before the right recipe was found.

The breakthrough finally came from John Schmalbach, a trusted worker from the Lancaster plant who visited for a single day. After a few hours, he found the combination of chocolate-making elements that Hershey wanted. The many trials finally yielded the Hershey Process, which would form the basis for the company's production for decades. The chocolate made with this recipe could be stored for several months without spoiling and although the fermentation of milk fat caused a slightly sour hint that Swiss chocolate lacked, Americans would come to expect the taste from their chocolate. In fact, other American manufacturers would have to add that taste to suit public demand.

The factory officially went into operation in the winter of 1904. Work slowed in Lancaster, and then transferred completely to Derry Church. As workers changed locations and new ones were hired, Hershey set about accommodating them. From the outset, he planned to build an entire town around his manufacturing complex. As Michael D'Antonio described it, the plan called for "a perfect American town in a bucolic natural setting, where healthy, right-living, and well-paid workers lived in safe, happy homes." Experience had taught the boss that employees appreciated being treated fairly. The town plan allowed them to live independently in a true community, complete with churches, stores, public trolley transportation and a fire department where he volunteered. Homes had modern amenities such as electricity, indoor plumbing and central heating during a time when less than 8% of American homes were wired for power. Architects also had instructions to give each new house its unique style and charm. In the following years, an amusement park, golf courses and a zoo were added to the budding community.

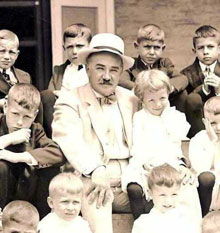

Milton Hershey credited his wife Kitty with the idea for his next great venture: a school for underprivileged boys. Kitty noted that although the childless couple traveled all over Europe and lived comfortably, they still had more money than they could spend. She suggested putting some of it toward a boarding school. Hershey dreamed of guaranteeing the students the well-rounded education that he never had. In addition to the usual writing and math, he wanted them to learn practical skills. "I want to see that every one of them learns a trade," he said. "Let them learn to earn their own livings. Some will want to be farmers, and they ought to be taught the best methods of farm management. But there will be others who want to be electricians, carpenters, type-setters or plumbers. We'll give them a chance to learn all these things."

Hershey thereby deeded 486 acres of farming land to the Hershey Trust Company for the construction of a school for orphaned boys. The Hershey Industrial School, which would later be renamed the Milton Hershey School, took in its first two students in 1909, followed by others from Lebanon, Harrisburg and beyond.

Jack Kerstetter, one of the thousands who have attended the school, compiled some of his recollections in his memoir, Behind the Chocolate Curtain. He described the place as one "set apart from the outside world, not as a fence around any school, or as a stone wall separating East and West Berlin, but just an invisible curtain founded by a man who had an idea and shared his love" (Qtd. Hinkle, 2004). Kerstetter wrote of how Hershey established a student work program whereby twelve-year-old pupils could earn 25 cents and then graduate to 50 cents at 15. The businessman also taught them to budget, encouraging them to put half of their earnings and allowances into a savings account. Upon graduation, he sent them into the world with $100, the same amount he had carried sewn into his jacket pocket as he had struggled to make a living.

In the early years, students lived in the very homestead on which Hershey had been born. Eventually the student body increased to the point of needing additional rooming space, and other buildings were converted to dormitories and kindergartens. Almost every year brought additional students, and that trend accelerated when the school started accepting girls as well as boys.

In the meantime, Hershey's company was growing as quickly as his school. In 1919, it earned $58 million, roughly equivalent to $273 million today according to the U.S. Federal Reserve. Mounting sugar prices associated with the ongoing world war caused problems, but even they could not topple the company. Although his company ran a deficit and had to allow a bank to mortgage the property and oversee control, M.S. Hershey increased production and efficiency company-wide to return Hershey's to the black by 1921.

Hershey also took the lead in securing his workers. During the Great Depression of the 1920s and 1930s, he gave jobs to about 600 construction workers from the area. Hershey ignored the advice of those close to him who said it was not the proper time to start a building campaign. Hershey saw that the community needed help and that supply costs were low. While much of the rest of the country sat unemployed, Hershey's workers built new hotels, schools, a community center, a stadium and a sports arena. All these new sights also created jobs in the tourist trade.

The Hershey influence stretched far beyond American soil. During World War II, for example, Hershey's supplied American troops in Europe and the Pacific with more a billion chocolate bars. Special "Ration D" or "Tropical" bars did not melt in the hot and humid Pacific theater. Parts of the plant in Hershey were even dedicated to churning out munitions. After the war, the company was awarded five Army-Navy E Production Awards for its service.

The Hershey brand expanded beyond those iconic chocolate bars and Hershey Kisses with such goods as Twizzlers, Icebreakers, Reese's, Almond Joy, Milk Duds, Mr. Goodbar, Bubble Yum and dozens of other varieties. Besides becoming the largest chocolate maker on the continent, the company also started new ventures. Hershey's Chocolate World, a visitor's center, opened with mascots, presentations, shows, shops and restaurants. The trust company ran, and continues to run, the Hershey Bears professional hockey team, Hersheypark, Hersheypark Stadium and the GIANT Center, all of which are situated in the town of Hershey.

Hershey kept busy in his old age with these investments and others things. He opened the doors of his mansion for the country club. He continued having business lunches with his managers, keeping close tabs on the company he founded. He still made regular appearances in the experimentation grounds at the factory. His nurses listened to many stories about his youth and his time with Kitty. On his 80th birthday, 6,000 Hershey's employees threw him a party at the arena, complete with a 3-foot-tall cake, four local bands, flowers, speeches and the children from his school.

Time finally caught up to Milton S. Hershey on October 13, 1945, when he died of a heart attack at 88. He died at the Hershey Medical Center a year after retiring from the board, and he is buried next to his parents and wife in the cemetery of the town that bears his name.

Before he died and without public fanfare, Hershey had willed the vast majority of his wealth to the Milton Hershey School through the Hershey Trust. Thanks to the stock shares and assets, the school is one of the wealthiest in the world. Its 1,300 students and staff enjoy about $66 billion in assets for its programs. More than for the huge company he built — with its nearly 14,000 employees and $4 billion annual sales — or for his personal riches, M.S. Hershey's legacy will endure through things such as his school. After all, this was a man who often proclaimed, "Business is a matter of human service." His public projects, his philanthropies and the true community he built all serve as lasting reminders of that conviction.

The new era without the long-time leader brought new challenges for the Hershey's. The brand's different branches developed sometimes strained and confusing relationships among one another. The commercial enterprises grumbled over their ownership by the Milton Hershey School and its trust. Other candy giants, particularly Mars and Nestlé, posed new competitive challenges.

Even if fierce competition within the industry and internal problems slowed growth, Hershey seems to have risen to the challenges. The company recorded about $4 billion in sales in 2005, led in part by active development of new goods for the new century, such as candy for dieters and variations of old favorites. Times have changed dramatically since the business officially began operating under the Hershey name in 1894, but it has shown it can adapt. Perhaps still greater challenges lay ahead.

Sources:

- D’Antonio, Michael. Milton S. Hershey’s Extraordinary Life of Wealth, Empire, and Utopian Dreams. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006.

- Hershey’s. 2008. The Hershey Company. 24 Mar. 2008. <http://www.hersheys.com/>.

- Hershey Company, The. 2008. The Hershey Company. 26 March 2008. <http://www.thehersheycompany.com/>.

- Hinkle, Marla. “Behind the Chocolate Curtain.” The Morning News (Ark.) 8 Feb. 2004. 26 March 2008 < http://taxguru.org/family/choccurtain.htm>.

- Shippen, Katherine B., and Paul A.W. Wallace. Milton S. Hershey. New York: Random House, 1959.

- “What is a dollar worth?” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. 2008. 25 April 2008 <http://woodrow.mpls.frb.fed.us/Research/data/us/calc/>.