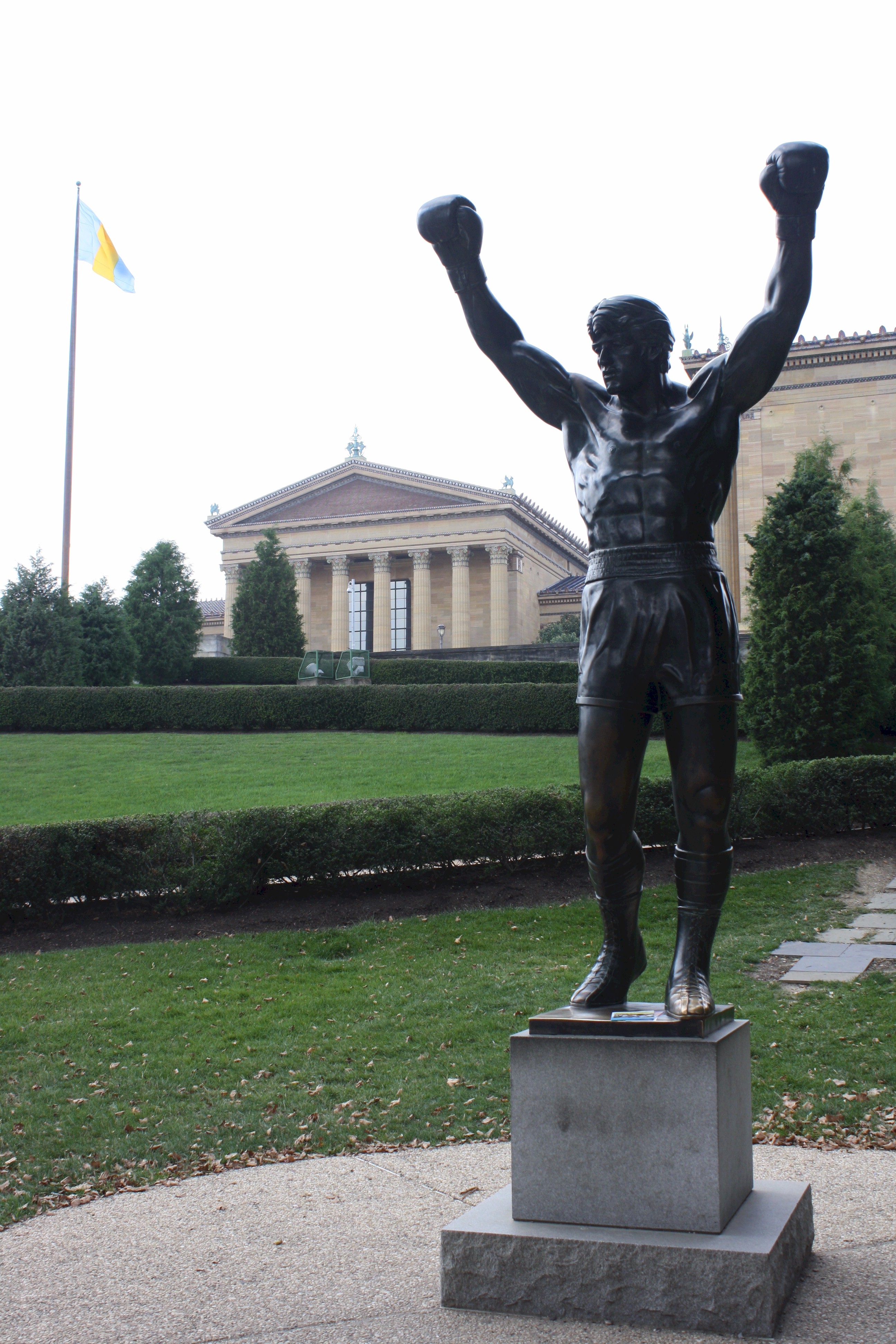

Atop the seventy-two steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art sit the bronze footprints that commemorate where film icon Rocky Balboa completed his fist-pumping training sessions. Rocky, the 1976 Academy Award winner for Best Picture, made the Philadelphia Art Museum recognizable in cinema houses throughout the world. Constructed during the 1920s, the Philadelphia Museum of Art was opened officially to the public on March 26, 1928. Known colloquially as "The Art Museum," it occupies a picturesque location at the west end of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Fairmount Park, overlooking the Schuylkill River. The Museum's exterior classical aesthetic both contrasts with and complements its contemporary exhibitions. Its Greek styled architecture houses over 225,000 pieces, including some of the most impressive artwork of the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries.

Many Philadelphia Museum of Art visitors—including most Philadelphiansémay not know that the current address of the Art Museum is not its original location. In preparing for the Centennial Exposition of 1876, the Pennsylvania state government proposed plans to construct Memorial Hall, intended as the art gallery of the exposition. After the celebration, Memorial Hall would remain open as Philadelphia's permanent art museum, titled the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art. Unfortunately, Memorial Hall was built on the west side of the Schuylkill River, preventing many Philadelphians from visiting. During these first decades at Memorial Hall, the Museum focused on the industrial arts, eventually expanding into fine and decorative arts as well. However, the growth at Memorial Hall was constrained both by limited funds and a cramped interior. At the turn of the century, the city of Philadelphia began considering alternative locations to build a new museum.

A proposal for a replacement building in the west side of Fairmount Park, at the end of a new parkway to City Hall, was submitted in 1907. Construction on the new structure began in 1919 and would last almost a decade. The primary architect hired by the Commissioners of Fairmount Park was Horace Trumbauer, a native Philadelphian. Working under Trumbauer was chief designer and fellow Philadelphian Julian Abele, one of the first notable African American architects in the United States. After four years of construction, the foundation and seventy-two broad steps had been laid. The architects designed the Museum to mirror the Fairmount Water Works, a nearby group of neoclassical buildings that once housed the city's waterworks.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art opened formally on March 26, 1928, proudly displaying sections devoted to British and American art. Historian Fiske Kimball, appointed Director of the Museum in 1925, was responsible for creating the "walk through time" collection of galleries on the principal exhibition space on the second floor. Philadelphia's Museum was one of the earliest American museums to employ this new technique of arranging galleries in historical sequence. Because of this commitment to displaying international art, the Philadelphia Art Museum was one of the first museums in the United States to import works from abroad. Kimball sent numerous curators to art markets throughout Asia and Europe with the goal of acquiring appealing artwork. This multinational presentation of art foreshadowed the dynamic, international culture of today's Philadelphia.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art's first years at its new location, coupled with its "walk through time" galleries, equaled a great success. Attendance records estimate over one million visitors to the Museum during 1928. However, during the financial fallout of the Great Depression in the 1930s, the cash-strapped city budget forced the Museum of Art to turn elsewhere to fund construction on the uncompleted galleries. Luckily, aid came in the form of federal grants from the Works Progress Administration. In spite of these setbacks, the museum continued to make strides to improve its growing collection. Under Kimball's leadership, the Museum seized an opportunity in 1928 to acquire the collection of French connoisseur Edmond Foulc, which included Gothic and Renaissance sculptures and a marble and alabaster choir screen dated 1535-40. The collection had a price tag of one million dollars, the largest single purchase ever made by a museum. Although the figure sounds excessive for the decade, the acquisition was possible because it was secured by an interest-free bank loan prior to the Stock Market Crash.

In addition to the Foulc items, the Museum of Art acquired other important collections during the 1930s. A series of paintings by Philadelphia artist Thomas Eakins were donated to the Museum by his heirs. The first significant group of photographs, 48 pictures by photographer Frederick Evans, was given by Eastman Kodak in 1932. J. Stogdell Stokes, Museum President from 1933-47, was responsible for raising funds to create distinctive theme rooms, including the 1600s Dutch room, the Indian temple hall, and the Chinese palace hall. Complementing these period rooms were the additions of individual masterpieces of Poussin's The Birth of Venus (1635-36) and Cezanne's The Large Bathers (1899-1906).

Coming out of the Great Depression, Director Kimball continued the Museum's emphasis on expansion through acquisitions in the 1940s and 50s. In March, 1940, the Museum opened its new Oriental Wing, which included seven galleries devoted to the arts of China, India, and Persia. Three years later, in 1943, the Museum of Art bolstered its display of Oriental carpets with the J.D. McIlhenny Collection, the largest compilation of objects to enter the Art Museum during these two decades. At the turn of the 1950s, the Museum was bequeathed a collection of modern European masterpieces from Walter and Louise Arensberg. This endowed collection included the largest non-Paris group of Constantin Brancusi sculptures and one of the premiere gatherings of Marcel Duchamp art pieces. As a whole, Kimball's acquisitions for the museum enabled it to achieve national recognition for its masterpieces of early modern art.

In 1955, Fiske Kimball resigned as Director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but his successor, Henri Marceau, would continue to expand the Museum. Through the rest of the 1950s, the Museum of Art acquired three notable collections: the J.L. Williams Memorial Collection of Oriental carpets (1955); fifteen galleries of Philadelphia furniture and silver (1958); and a suite of thirteen Roman tapestries depicting the life of Constantine the Great (1959). These noteworthy additions expanded the diversity and quality of the Museum's possessions.

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, the Art Museum continued growing through key acquisitions and capital development. In 1964, under the capital program of the city of Philadelphia, the Museum began construction of the Armory atop the Great Stairs. The Armory would function as a display for the Otto Kretzschmar von Kienbusch Collection of Arms and Armor. When these galleries finally opened the next decade, they were some of the most visited spots in the Museum. In addition to the Arms and Armor Collection, Director Kimball acquired two impressive collections of nineteenth and twentieth century French paintings. In 1964, after nearly a decade in service for the Museum, Kimball stepped down, enabling Dr. Evan H. Turner to become the new Director.

In preparation for its centennial celebration, the Museum finally approved plans for building-wide air conditioning in 1973. The project was completed over three years, just in time for the gala. At the same time, the Museum designed and constructed a new 13,500-square-foot special gallery for touring exhibitions. The year 1976 marked the centennial celebration of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, highlighted by over five hundred pieces of art received through its "Gifts to Mark a Century" donation campaign. These gifts included photographs by American Ansel Adams and modern paintings by artists De Kooning, Monet, and Pollock. Responding to the growing interest of fine craft arts the following year, the Museum played host to the first Philadelphia Craft Show in November, 1977. Organized by the Women's Committee, this annual Craft Show became one of the finest exhibitions and sales of contemporary American crafts. Today, this show remains the largest yearly fund-raising event for the Art Museum.

At the close of the decade, the Museum acquired three noteworthy collections: the C.D. Wright Collection of fifty-one Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings; the A.M. Clark Collection of over 500 Italian prints, with strengths of the eighteenth century; and the F.P. and A.N.B. Garvan Collection of roughly 4,000 Dutch tiles from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The Museum would continue this practice of acquisitions through purchases, donations, and bequeaths throughout the rest of the twentieth century.

Despite the numerous additions during its first hundred years, the 1980s and 90s proved to be one of the most active acquisitions periods for the Museum. As the 80s decade opened, the Museum appointed a new Director, Jean Sutherland Boggs. Around the same time, the Museum received a staggering 500 original prints from the Estate of Paul Strand. Through a major grant from the Pew Charitable Trusts in 1985, the Museum acquired the wood sculptures Comedy and Tragedy of Pennsylvania native William Rush, considered America's foremost sculptor. The next year, in 1986, the Art Museum received an even more impressive gift than acquisitions earlier in the decade. One of the finest private collections of the century, the H.P. McIlhenny Collection included nineteenth century masterpieces by artists like Seurat, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Van Gogh.

That same year, the Museum's trustees endorsed the Landmark Renewal Fund (LRF) of $50 million, allocated for the repair and renovation of the sixty year old building. Three years later, in 1989, a court decision facilitated the Museum to combine the J.G. Johnson Collection of private European art, previously installed in its own gallery, with the Museum's other holdings of the same periods. This combination enabled the Museum to display European art from 1100-1900 as an interrupted "walk through time" exhibit, one of its favorite display methods. To balance with these investments in older art, the Museum pursued acquiring works by contemporary artists in the 1980s. These recent pieces include an installation by Joseph Beuys, a sculpture by Anselm Kiefer, and a ten part room-sized painting by Cy Twombly.

During the 1990s, the Museum underwent a series of repairs and renovations. It raised the initial LRF campaign goal by $10 million in order to renovate several dozen European galleries and period rooms, over one-third of the Museum's exhibition space. In the midst of reconfiguring its layout of artwork, the Museum acquired an important portrait by African American artist Henry Ossawa Tanner, a native of Philadelphia. In addition to this portrait of the artist's mother, the Art Museum had already been the first American museum to purchase a major painting by Tanner. With its increased endowments and impressive compilation of art from all time periods, the Philadelphia Museum of Art celebrated its 125th anniversary in 2001.

As the Museum took time to cherish its history, it also outlined its future goals for the next decade in a 10-year master plan. The proposal entails a thorough expansion and renovation of the interior without changing its familiar exterior, adding 80,000 square feet for public space. Although the Museum appears massive from the outside, its interior designs are too small to adequately display the Museum's holding. The project, estimated to cost $500 million, will be under the direction of famed architect Frank Gehry. However, since the Museum does not want to disrupt its iconic exterior, the expansion will be entirely underground. This commitment to presenting masterworks of art in dynamic galleries will ensure that the Philadelphia Museum of Art remains one of America's finest museums.

Responsibility for the impressive acquisitions and planned renovations at the Philadelphia Museum of Art during the last few decades can be assigned to the legacy of Director Anne d'Harnoncourt. She occupied the director position from her appointment in 1982 until her death in 2008. After a nationwide search for a successor, the Museum named Timothy Rub as its thirteenth director in 2009. Rub, a previous director at the Cleveland Museum of Art, summarized his art museum philosophy to Bobbi Booker of Philadelphia Tribune: "It's about access to the arts." Under Rub's direction, the Art Museum will continue its exciting combination of continuity and change.

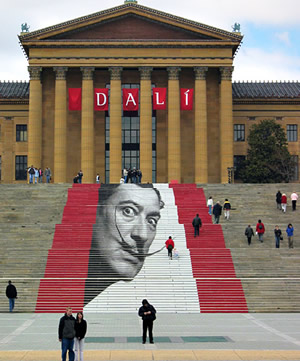

In her 1928 article, "Philadelphia's New Museum," in The Burlington Magazine, an international periodical for fine arts, Ella S. Siple boasted that "this great museum of art will dominate the scene" of Philadelphia. She continued her praise of the Art Museum with an extraordinary comparison to antiquity: "Philadelphia looks up to it as Athens looked to her Acropolis." The Museum functions as impressive beacon of art from the past to the present for both international and local visitors. International exhibitions such as Cézanne (1996), Van Gogh: Face to Face (2000-01) and Frida Kahlo (2008) have all appeared at the Art Museum in Philadelphia. In addition, the Museum proudly holds artwork from native Pennsylvanians like impressionist Daniel Garber and realist Thomas Eakins in its permanent collection.

In addition to its interior galleries and exhibitions, the facade of the Philadelphia Museum of Art—and its seventy two steps—have become cultural icons. These steps are not just the location of July 4th concerts celebrating Independence Day, but they were also the only U.S. concert location during the international Live 8 festival on July 2, 2005. Estimates suggest that over one million visitors converged on Ben Franklin Parkway to see Will Smith, Maroon 5, Stevie Wonder, and other musicians perform on the Art Museum steps. The Philadelphia concert, like the other ten shows, was simulcast throughout the world on television and the internet. As a result of this publicity, the Philadelphia Museum of Art steps can be recognized internationally, even to people unfamiliar with Rocky.

Providing a rich cultural influence of the city of Philadelphia, the Art Museum is a masterpiece inside and out. Like the exhilaration that film character Rocky experienced, the climb up the seventy-two stairs rewards each visitor for every footstep. The combination of an expanding collection of art with engaging exhibitions ensures that no two trips are ever the same. Traveling to the Philadelphia Museum of Art remains a captivating experience for the first-time tourist and regular visitor alike.

Sources:

- "Awards for Rocky (1976)." The Internet Movie Database. 2009. 24 Jul. 2009. <http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0075148/awards>.

- Booker, Bobbi. "Philadelphia Museum of Art Board Names New Leader." Philadelphia Tribune. 125:66 (30 Jun. 2009): A1.

- "The Concerts: Museum of Art, Philadelphia." LIVE 8 Concerts. 17 Jul. 2006. 25 Jul. 2009. <http://www.live8live.com/theconcerts/index.shtml>.

- Gelbart, Marcia. "Philadelphia Mayor Sees Live 8 Benefit Beyond Costs." Philadelphia Inquirer. 9 Jul. 2005: B1.

- "Museum History." Philadelphia Museum of Art. 2009. 25 Jul. 2009. <http://www.philamuseum.org/information/45-19.html>.

- Pogrebin, Robin. "Philadelphia Museum Job Sends Gehry Underground." New York Times. 26 Oct. 2006: E1.

- Siple, Ella S. "Philadelphia's New Museum." The Burlington Magazine. 52:302 (1928): 254—56.