Some say it was radiation, some say there was acid on the microphone,

Some say a combination that turned their hearts to stone,

But whatever it was, it drove them to their knees.

Oh, Legionnaires’ disease.I wish I had a dollar for everyone that died within that year,

Got ‘em hot by the collar, plenty an old maid shed a tear,

Now within my heart, it sure put on a squeeze.

Oh, that Legionnaires’ disease.Granddad fought in a revolutionary war, father in the War of 1812,

Uncle fought in Vietnam and then he fought a war all by himself,

But whatever it was, it came out of the trees.

Oh, that Legionnaires’ disease (“Legionnaires’ Disease,” Bob Dylan).

Bob Dylan’s song lyrics capture the feeling of confusion and conspiracy that diffused throughout the nation after an American Legion convention in Philadelphia left members with a deadly pneumonia.

The Legion members were celebrating America’s bicentennial; the momentous occasion brought them all to the Bellevue Stratford Hotel on a hot weekend in July of 1976. The illness progressed in the members after they returned to their homes, all suffering from headaches, chest pains, fever, and lung congestion. Dr. Ernest Campbell, a physician from Bloomsburg, Columbia County, was the first to see a pattern in the outbreak of illness after he found that three of his patients with similar symptoms had attended the conference.

Among the 182 persons infected, 147 required hospitalization, and 29 died. It was a disheartening time for members of the American Legion. They mourned their friends who had survived wartime, only to fall ill celebrating the legacy of their homeland. Scientists at the Center for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia, scrambled to identify what kind of infectious agent was responsible for such a lethal outbreak. The American public waited in anticipation. Was it bioterrorism? Foul play? Was it an infectious microorganism, or a toxin? “Sabotage is an easy possibility to consider,” said Dr. Lewis Polk, Philadelphia’s health commissioner, “but there is no evidence to lead us to that conclusion.”

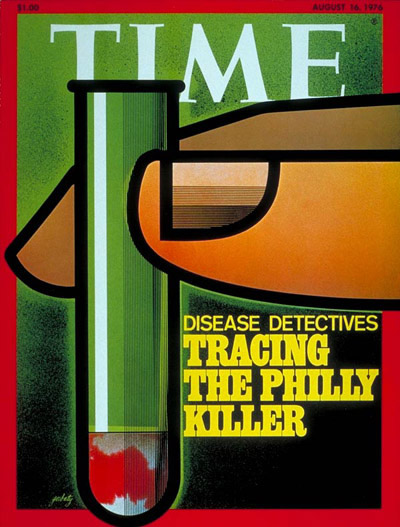

TIME Magazine’s August 1976 cover story “Disease Detectives: Tracing the Philly Killer” glorified the efforts of CDC scientists on the trail, citing not only the need to determine “whodunnit”, but the noble sleuth’s responsibility of finding out how. The cover article sheds light on the elusive nature of the pathogen. Though it is now known that a microorganism caused the pneumonia outbreak, the journalist claimed the “detectives” had ruled out microorganisms and had moved on to toxicological agents - chemicals and heavy metals.

After nearly six months of head-scratching, scientists at the CDC were downright embarrassed that no one had yet found the culprit, let alone how the infection had spread. TIME Magazine ran another story in January, 1977 called “Found: The Philly Killer, Perhaps,” that reported a persistent CDC scientist Dr. Joseph McDade’s success in identifying a novel rod-shaped bacteria. He recalled later that the process by which he found the bacteria was, “like searching for a missing contact lens on a basketball court with your eyes four inches away from the floor.” After finding nothing looking like a known pathogen, McDade set out to look for something—anything—that he didn’t recognize. Although he had no idea what he was looking for, the molecular and immunological techniques he used were perfect for identifying the culprit bacterial pathogen. The bacteria were later named Legionella pneumophila.

Library of Congress

It is now known that Legionella pneumophila thrives in warm water and warm, damp places. The month of July is hot and balmy in the city of Philadelphia and the Bellevue Stratford Hotel offered air-conditioned rooms for the comfort of their guests. Unfortunately, cooling towers are the perfect breeding ground for Legionella pneumophila, and its dissemination through the Bellevue Stratford Hotel was facilitated by the air conditioning.

Since its discovery in 1977, Legionella pneumophila has been extensively characterized. Scientists have found the pathogenic microorganism to be responsible for outbreaks since then. There are classical symptoms that set Legionnaires’ disease apart from other pneumonias. Symptoms include high fever, headache, dry cough, chest pain, difficulty breathing, diarrhea, confusion, delirium, vomiting, nausea, and failure to respond to beta-lactam antibiotics, the type of antibiotics usually used for pneumonia. If Legionnaires’ disease is suspected, beta-lactam antibiotics can be given in conjunction with another antibiotic.

L. pneumophila thrives in warm, damp places. The bacteria are ubiquitous in freshwater environments like lakes, rivers and wet soils (Phares). L. pneumophila is primarily spread via inhalation of infected aerosols. One perfect place for this bacteria to grow is cooling towers and air-conditioning systems, as was the cause of the 1976 outbreak in Philadelphia. However, L. pneumophila preference for aquatic environments has proven to be a global health issue, as it has been the major pathogen in six notable outbreaks around the world. These outbreaks have caught the attention of the World Health Organization (WHO) which has devised approaches to control cooling tower environments, and develop water safety plans.

According to the World Health Organization, “the fact that Legionellae are found in hot-water tanks or thermally polluted rivers emphasizes that water temperature is a crucial factor in the colonization of water distribution systems.” These characteristics mark Legionella pneumophila as a fastidious bacteria, which means it thrives in artificial conditions.

The World Health organization has taken initiative in the characterization of Legionnaires’ disease and its epidemiology. Epidemiology is the branch of medicine dealing with the incidence and prevalence of disease in large populations and with detection of the source and cause of epidemics of infectious disease. Common environments for Legionella pneumophila are potable water distribution systems, cooling towers and evaporative condensers, health care facilities, hotels and ships, and natural spas, hot tubs, and swimming pools. Hospitals and other health care facilities pose challenges for L. pneumophila prevention because these often have older, more complex plumbing systems, and many persons who may be highly susceptible to infection. The concern for this pathogen has spread far outside the city limits of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

WHO has described ways for disease surveillance and public health management of outbreaks to be possible at a national level. Though implementing surveillance systems in countries depends greatly on such factors as: infrastructure and public health laws, surveillance law, notification law, data protection, and patient confidentiality, WHO stresses that it is of great importance. Efficient identification and communication of an outbreak is essential because time is a major factor for the survival of those who become infected.

The WHO is a leading authority on disease outbreak and epidemiology. Their thorough recognition, surveillance, and regulation of Legionnaires’ disease, has surely improved the lives of many.

Thankfully, the “Philly Killer” is no longer at large in Philadelphia. Though more is known now about Legionnaires’ disease, it is still a significant health concern throughout the world. The historic event at the Bellevue Stratford Hotel inspired a race for knowledge that resulted in the ultimate characterization Legionnaires’ disease, and the identification of a novel human pathogen – Legionella pneumophila.

Sources:

- Cantwell Jr., Alan, MD. “The Lessons of Legionnaires’ Disease.” AIDS: The Mystery and the Solution. 2nd Edition, Revised. Los Angeles: Aries Rising Press, 1986. 118-123.

- Dylan, Bob. Lyrics, 1962-1985. New York: Knopf, 1985.

- “epidemiology.” Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. 13 Apr. 2010. <http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/epidemiology>.

- Fraser, D.W., Tsai, T.R., Orenstein, W., Parkin, W.E., Beecham, H.J., Sharrar, R.G., et al. “Legionnaires’ disease: Description of an epidemic of pneumonia.” New England Journal of Medicine, 297 (1977): 1189-1197.

- McDade, J.E., Shepard, C.C., Fraser, D.W., Tsai, T.R., Redus, M.A., & Dowdle, W.R. “Legionnaires’ disease: Isolation of a bacterium and demonstration of its role in other respiratory disease.” New England Journal of Medicine. 297 (1977): 1197-1203.

- Phares, Christina R., Moore, Matthew R. “Legionellosis, Legionnaires Disease and Pontiac Fever.” Emerging Infectious Diseases. Ed. Felissa R. Lashley Jerry D. Durham. 2nd Edition. New York: Springer Publishing Company, 2007. 243-254.

- TIME Magazine. “Medicine: Found: The Philly Killer, Perhaps.” 31 Jan. 1977. Mar. 2010 <http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,918638,00.html>.

- TIME Magazine. “Medicine: The Disease Detectives.” 16 Aug. 1976. Mar. 2010 <http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,914555-1,00.html>.

- TIME Magazine. “The Philadelphia Killer.” 16 Aug. 1976. Mar. 2010 <http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,914553-1,00.html>.

- World Health Organization. “Legionella and the Prevention of Legionellosis”. Ed. Yves Chartier, John V Lee, Kathy Pond and Suzanne Surman-Lee Jamie Bartram. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007.