"From this point to the base of the Blue Mountain the rocks formation is slate, excepting a narrow point of limestone on the Delaware, at the mouth of Cobus creek, below the Water gap, which, after extending a short distance westward, sinks beneath the overlying slate. The surface of this slate region is generally hilly, and the soil but moderately productive. Extensive slate quarries have been opened in this county, which yield slate of a superior quality, both for roofing and for manufacture into school slates." —Wm. H. Egle, Illustrated History of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 1876

As one travels through the region of the Blue Mountain mentioned by Egle, odd, hulking forms haphazardly decorate the otherwise sleepy, peaceful scenery on either side of the road. Massive piles of slate, pulled straight from the earth and deemed unworthy for use, stand as enduring sentinels to a once booming and pivotal industry in Pennsylvania. These sleeping giants herald a visitor’s entrance into the Slate Belt, an area of Northampton County, Pennsylvania rich in cultural influences and a history built around the durable and once very profitable industry.

Unbeknownst to Egle, this area would someday become the world’s leading slate producer, bearing the name “Slate Belt” as a result of its high-quality slate output.

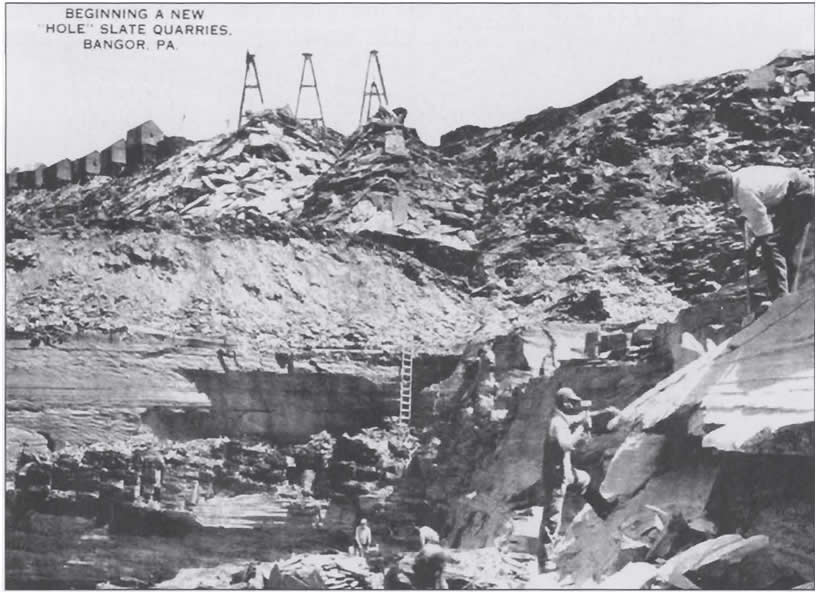

While independent slate quarries had existed for decades in the region, the slate industry proper in Northampton County had its humble beginnings with the enterprising Robert M. Jones, an immigrant from north Wales. An experienced slate worker himself, Jones came to America in 1848 in search of an area in which to begin new slate quarries. The area he found was Bangor, Pennsylvania, so named by him because it resembled Bangor, Wales in its overall appearance and slate characteristics. The industry started in Bangor soon spread to its surrounding towns of Pen Argyl and Wind Gap, making up the majority of the region now known as the Slate Belt. Many small quarries began to open up, run by individuals rather than large corporations. The quarrying of slate required large amounts of labor, employing many men and contributing to the immigration of many groups interested in profiting from the industry. Slate quarrying in the region grew steadily through the late 1800’s and hit its peak in production around the turn of the 20th century. By 1903, the year when slate production hit its highest point, the Slate Belt was the largest slate-producing region in the world. With millions of dollars in revenue generated every year during its heyday, the slate industry contributed significantly to the formation of Pennsylvania’s economy.

The beautiful, durable blue-gray rock produced in the area had its own illustrious history on a geologic time scale. A metamorphic rock formed from shale by the influences of heat and pressure, slate was formed over millions of years into a hard, resistant material suitable for use in many applications. It possesses a grain that contributes to distinctive physical characteristics, making it suitable for splitting into thin sheets. Depending on the mineral content within its precursor rocks, slate can take on many colors, including black, gray, red, green, purple, and other hues. In the Slate Belt, the mineral content led to the familiar dark blue-gray color.

Due to slate’s durability and resistance to hard wear, slate production became profitable in the Slate Belt for a myriad of uses. Blackboards, slate gravestones, and miniature slate boards for use in classrooms of the time were significant uses of the rock. However, the vast majority of the slate was mined for a singular purpose— the production of roofing tiles. Slate is highly resistant to weathering and can last hundreds of years after installation on a roof. According to Charles Capozzolo, a co-owner of an operational quarry in Bangor, Pennsylvania, “Take a look at old houses from here to Philadelphia. They all have slate roofs. Those roofs could last hundreds of years.” Indeed, many houses built prior to the 1900’s in Pennsylvania still bear the unmistakable mark of the Slate Belt— enduring slate roofs protecting them from the elements.

Slate that could not be used for roofing was overwhelmingly wasted, left in the mountainous piles of slag that still dot the countryside of the Slate Belt. In E. Willard Miller’s Pennsylvania: Keystone to Progress, the geographer notes that between 60 and 80 percent of the slate quarried was deemed unfit for use, and it was subsequently left in refuse piles up to 100 feet in height.

The work of a slater (a local term for a quarry worker) was seldom easy. The typical day for teams of slaters consisted of hard, dangerous labor in a quarry sometimes hundreds of feet deep, where rock slides and other accidents were an ever-present reality. After the topsoil and debris were removed from the slate bed, the raw stone needed to be removed. In the early days of quarrying, the slate was removed from the beds using dynamite explosives, creating jagged chunks of rock. Because they left behind large amounts of shattered waste slate, explosives were eventually replaced by more efficient means of cutting and removing the rock. Melissa Hough notes in The Centennial Book that “the bar channeller, introduced in 1887, was a twelve foot bar supported on four legs on which drills were mounted and these made holes close enough together to form a line.” Ten years later the bar channeller was replaced by the track channeller, and then by the wire saw in 1926. Today’s quarries still employ the use of the wire saw in their operations.

After the rock was pulled from the bed, it was split across the grain and lifted from its place in the bed by teams of men with long metal bars. The giant slab was then hoisted precariously to the top of the quarry in a chain sling, a dangerous but necessary operation. From here, skilled workers split the slate along the grain to determine its usefulness for roofing slate. According to Hough, “If it split thinly, it became roofing slate; if not, it became blackboards or structural pieces.” The job was uncomfortable and damp, because slate can only be split while wet. Finished roofing shingles and other slate products, after trimming, were stacked in the quarry yard to await shipment. Charles Capozzolo, of the Capozzolo Brothers Slate Company, noted that the typical slater was generally paid by the piece, wherein each acceptable slate product he produced contributed to his pay. This increased the output of the slate workers.

So what happened to the slate industry in Pennsylvania? Once boasting numbers of operational quarries into the hundreds, the Slate Belt’s namesake industry has been reduced to but a shadow of its former glory. Only three operational Slate Belt quarries are in existence today— one each in Wind Gap, Pen Argyl, and Bangor. The massive reduction in slate production can be traced to several causes. Capozzolo accounts for a common reason for a quarry to shut down, even during the bustling heyday of slate production— hard tack. “Hard tack is a rock formation that runs through the earth like normal slate beds. Once you hit that, the quarry was done.” Hard tack is a deformed, unusable slate material that often accompanied useful beds of slate. Its discovery meant that the productivity of the quarry was at an end.

Another reason for the slate industry’s decline was the advent of asphalt roofing tiles in the early 1900’s. Cheaper and lighter, these tiles were easier to apply to a roof and required less skilled labor than the application of slate tiles. Houses that would have needed to bear the weight of the heavy slate tiles were built lighter and less durably, with thinner beams and loading-bearing structures. This left them unable to use slate roofs even after their much less durable asphalt roofs needed repair. This shift to asphalt roofs put more quarries out of business.

World War I also led to the shutdown of many quarries, as men who once worked in them moved to work for the war effort. Many of them never returned to the quarries after the war, keeping them closed forever. One of the largest contributors to the shutdown of quarries was, according to Capozzolo, the Great Depression. “No houses were being built, so you couldn’t sell slate for roofs. Many quarries went under as a result.”

All of these factors led to an overwhelming decline of the quarrying industry in the Slate Belt, leaving few Pennsylvanians with a sense of the Slate Belt’s influence in the state’s formation. However, the Slate Belt’s legacy is still visible through the enduring slate products still in existence in Pennsylvania, as well as through the descendants of the migrant slate workers in the areas surrounding the towns of the Slate Belt. One of the most noticeable legacies of the Slate Belt, the ethnic heritage of the area stands out as a miniature melting pot comprising many groups.

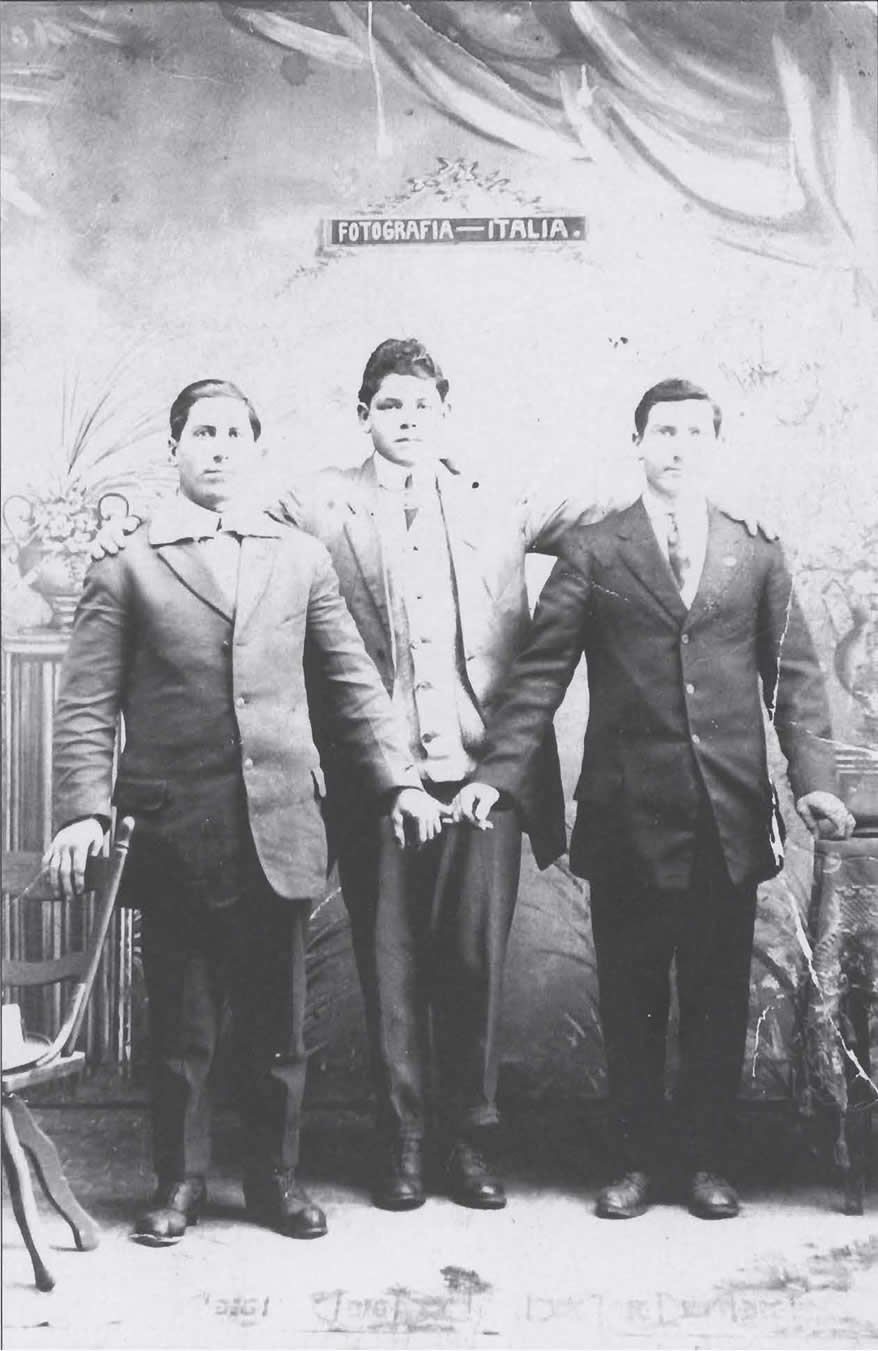

Italian immigrants to the Slate Belt pose for a picture. The Italians contributed a large amount of labor to the quarries and influenced the ethnic mix of the area.

The first immigrants to the area were skilled slate workers from Wales and Cornwall, England, following in Robert M. Jones’ footsteps in the 1850’s. The Cornish hailed from a village known as Delabole, where they were quarrymen in the Old Delabole Quarry, now one of the oldest and largest quarries left in the United Kingdom.

The Pennsylvania Dutch (German) immigrants that steadily trickled into the area during the slate industry’s formative years contributed both labor to the quarries and a lasting mark on the agriculture in the Slate Belt region. Several Pennsylvania German farms are still in existence in the areas surrounding the Slate Belt. Large waves of Italians, most notably from Roseto, Valfortore, came to find work in the quarries that would give them any opportunity greater than what they could grasp in their homeland. They would later form their own small town between Pen Argyl and Bangor, named Roseto in honor of the village from which they predominantly came. The turn of the 20th century brought large numbers of the four most prominent slate quarrying groups- Welsh, Cornish, Germans, and Italians.

Small numbers of Scotch-Irish, French Huguenots, Irish, Jews, Poles, African-Americans, and Asians contributed to the area as well. With the influx of so many differing peoples, ethnic tensions arose inevitably among settlers in the Slate Belt. As the Commemorative Book Committee of Bangor’s 125th Anniversary Book stated, “there was a certain jockeying for position, and a changing definition of what constitutes being ‘American.’” People from a specific ethnic group generally associated with those in the same group, seldom mixing with other ethnic populations. Conflicts arose, and ethnic factions, by necessity, adapted to the new situations. Whatever the racial and ethnic strife between the groups, they were all united by the desire to make a better life for themselves through work in the Slate Belt, and the slate quarries were the primary reason for that work.

Today, the slate quarries that built the Slate Belt lie primarily abandoned, ghosts of a once booming and necessary industry in Pennsylvania’s economy. The towns in the Slate Belt are now primarily residential, no longer industrial centers of the state. However, to see the influence of the Slate Belt in Pennsylvania’s formation, one need only look at the beautiful, durable slate still in use from decades past, serving as rooftops, blackboards, and tombstones. They serve as enduring, stalwart reminders of an industry that helped build the state of Pennsylvania.

The Slate Belt Heritage Center in Bangor seeks to preserve the memories and artifacts of the Slate Belt and its heyday. In two floors in the former Bangor Town Hall, the Heritage Center offers self-guided exhibits on the various immigrant groups in the region, the tools of the slate trade and other aspects of life in the Slate Belt. Online exhibits and hours of availability can be found http://www.slatebeltheritage.com.

Sources:

- Bangor 125th Anniversary Commemorative Book Committee. The 125th Anniversary Book: Bangor, Pennsylvania. 1875-2000. Bangor, PA: Slate Belt Printers, 2000.

- Capitol Slate Company. Slate Roofs. 3rd ed. New York: National Slate Association, 1953.

- Capozzolo, Charles. “Interview With an Owner of an Operational Slate Quarry.” Personal interview. 9 Mar. 2010.

- Egle, William H. The History of Northampton County. Philadelphia and Reading, PA, 1877. History of Northampton County Pennsylvania. Northampton County Pennsylvania Genealogy Project, 2004. 8 Mar. 2010. <http://northampton.pa-roots.com/history.html>.

- ExplorePAHistory.com. 8 Mar. 2010. <http://explorepahistory.com/hmarker.php?markerId=1041>.

- Hough, Melissa, ed. The Centennial Book: Bangor, Pennsylvania. 1875-1975. Bangor, PA: Commemorative Book Committee, 1975. 47-50.

- LaPenna, Cindy. Images of America: Around Bangor. Charleston: Arcadia, 2005. 13-38.

- Miller, E. Willard. Pennsylvania, Keystone to Progress: an Illustrated History. Northridge, CA: Windsor Publications, 1986. 87-90.

- Pen Argyl Centennial Book Committee. Ring the Bells for Olde Pen Argyl: 1882-1982. Pen Argyl, PA: Pen Argyl Centennial Committee, 1982. 5.

- Schaumburg, William C. Pennsylvania Slate: An Introduction to One of North America’s Oldest Industries. Newton, NJ: Carstens Publications, 2007. 1-5.