Visit PA Media Room

In 2010, Pennsylvania was named Best in the Nation for state parks. To celebrate the honor, the state held a large ceremony in Ohiopyle State Park, about sixty miles south of Pittsburgh. Ohiopyle State Park is one of Pennsylvania’s largest parks, and boasts a unique beauty, a historic past and over a quarter million guests each year. Ohiopyle’s fourteen-mile-long Youghiogheny River contains some of the best-loved water recreation areas in the state. Organizers of the celebration could think of no better place for the celebration than Ohiopyle. Park manager John Hallas optimistically calls Ohiopyle State Park a place for “recreation with a purpose.”

Before the establishment of Ohiopyle State Park, southwestern Pennsylvania was scarcely explored or settled. In the mid-1700s Native American tribes, such as the Monongahela, owned the land. However, Native American populations were depleted due to frequent wars with the Iroquois Nation. The name Ohiopyle derives from the word ohiopehhla, meaning “white, frothy water—” an adequate description for the rapid-flowing Youghiogheny River.

Tim Palmer, the author of the Youghiogheny River, describes Ohiopyle as "like an island— to get there, you [had] to want to get there." Early European travelers relied on the Youghiogheny to explore and discover alternate routes in the Ohio River Valley region. Europeans recognized the importance of the Youghiogheny River— it could be a strategic route to the area that is now Pittsburgh. Europeans bought Native American’s land for complete control of the area. By the mid-1750s, the British, the French and the Iroquois all desired the Ohio River Valley region.

The Youghiogheny River played a pivotal role in the French and Indian War when British General Edward Braddock and his troops— including a young George Washington— used the river to confront French troops at Fort Duquesne. Braddock’s battle against the French was a devastating defeat for the British; however, the roads that Braddock and other British Generals constructed to reach the Ohio River Valley region brought many European settlers to Ohiopyle. These same roads led to the eventual defeat of the French and secured the Ohio River Valley for the British. However, the British declared the land to be Native American territory and asked European settlers to leave, though they were reluctant to do so. This exodus was brief, as King George III re-purchased the land from the Iroquois in 1768— leading to the return of European settlers in the Ohiopyle region.

After the American Revolution, problems arose in the Ohiopyle region after citizens revolted against a tax on whiskey. President Washington imposed the tax in order to centralize and fund national debt in the newly-formed country. To alleviate the problem, Washington sent militiamen to the region and effectively disarmed the violent dissenters.

In the 1800s, more settlers moved to the Ohiopyle region. These settlers were mostly farmers, hunters, and trappers. During 1811, a road was built that passed near Ohiopyle, giving people and markets better access to the area. Easy accessibility allowed lumber industry to thrive, and became an economic stronghold in Ohiopyle. The lumber industry erected a large mill by Ohiopyle Falls, bringing workers from outside of the region. By 1871, three major railroads— Baltimore, Ohio and Western Maryland— made routine stops in town. The railroads offered tourists easy access to Ohiopyle. A ride from Pittsburgh to Ohiopyle and back only cost $1. The area became a popular destination for Pittsburgh residents on vacation. Increased tourism led to the town’s development. Hotels, a bowling alley, walking paths, tennis courts, ball fields, fountains, a boardwalk at Ferncliff Peninsula and a dance pavilion were established by the 1880s.

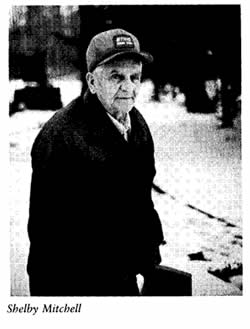

Ohiopyle was growing fast, and the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy saw the natural beauty of the area and purchased much of the property. Pennsylvania purchased the land in the mid-1960s and sought to return Ohiopyle to its former natural state. Forests thrived at the removal of buildings. Now known as Ohiopyle State Park, it caters to over a quarter million visitors per year and recently constructed a state-of-the-art visitors center. The park offers various activities such as camping, biking, hiking, whitewater rafting, gorgeous scenery and natural habitats. Many vacationers love travelling to Ohiopyle during the summer months. However, local resident, Shelby Mitchell— who was born in the Ohiopyle House, now the office of Ralph and Mike McCarty’s Mountain Streams and Trails rafting company— recognizes how different the area used to be and states:

Old Ohiopyle was a very different place. There was none of this rafting business. But we sure had a good time. Right there at the Falls, on the Ohiopyle side, sat the old power plant— a big three-story building that was first used as a mill, later changed by the Kendall Lumber Company to make electricity for their sawmill and for lights in the town.

He also explains the Youghiogheny River’s improvement since the inception of the Ohiopyle State Park:

That river's a whole lot better now than it was. There were no fish- the tannery and the mine'd killed 'em all. We cut ice in the winter and pack it in sawdust. People'd come’n get it, and the hotel and different places had it, but then we got typhoid epidemic. A lot of people died, maybe from that ice, some thought. That was back around World War I.

The splashing waters of Ohiopyle Falls roar in the heart of Ohiopyle State Park. It stands twenty-feet tall and can be seen from an observation deck or on a hiking adventure through the Ferncliff Peninsula. Tourists can view the frothy water best in the springtime, when the water flows most heavily. For hikers, a trail that begins on the side of the observation deck allows for a closer view of the side of the waterfall. Visitors picnic here and enjoy lounging in the cool mist of the waterfall.

The Ferncliff Peninsula offers breathtaking views of the Ohiopyle Falls. Fernwood Trail permits hikers to stroll along the riverbank and straight through the large peninsula. Oddly, the Youghiogeny River flows northwards beside the peninsula. The director of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy’s natural areas programs, Paul Weigman states, “The north-flowing river is unique in its transit of southern seeds to a northern gorge, protected by its deepness from the coldest weather.” The northward flow of water brings a plethora of rare plant life to the Ferncliff Peninsula. In 1916, Dr. O. E. Jennings, Pittsburgh botanist, and other scientists found eighty-seven species and varieties of woody plants. Rare plants drew attention: Barbar’s Buttons and Carolina tassel-rue, are found in no other place in Pennsylvania. Other rarities of Ferncliff Peninsula include: Slender blue iris, autumn willow, and buffalo-nut. Old-growth trees and the state flower, mountain laurel, can also be found in abundance.

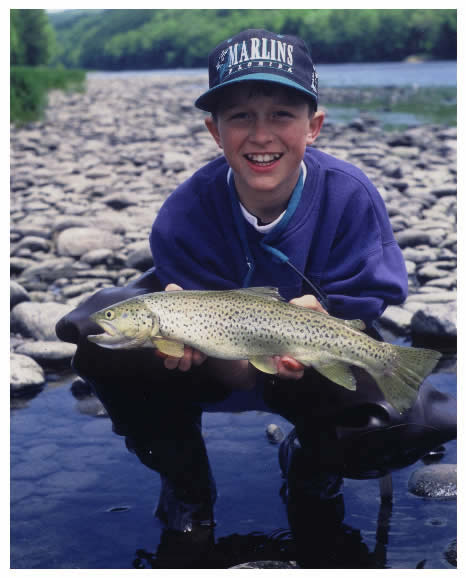

Nestled in the park is Meadow Run. The most popular attractions at Meadow Run are the natural waterslides. Years of erosion from stream water carved the rocks to form the slides. The flow of Meadow Run can change drastically due to the heavy rainfall or no rainfall at all. Visitors leap into cool waters from a huge boulder found beside a serene waterfall.

The most visited attraction in the park is Cucumber Falls. It has a beautiful ravine and a thirty-foot drop. The Cucumber Falls’ Trail Head offers a great view of Ohiopyle’s natural surroundings. During rainy months, the Cucumber Falls swell at their fullest with the rush of whitewater. At the bottom of the falls, visitors relax and swim in a shallow natural pool. The trail also leads to the Youghiogheny River, where kayakers or rafters tackle the Cucumber Rapids.

Ohiopyle State Park not only flaunts its natural beauty— but also its splendid camping accommodations. Ohiopyle is home to many stunning woodlands campsites as well as affordable hotels for a luxurious stay. There are over 27 miles of flat trails and about 14 miles of mountain biking trails, and over 90 miles of hiking trails around the park and campsites.

George Washington may be well known for crossing the Delaware River, but he certainly struggled with the Youghiogheny River. As Washington paddled downstream in a canoe, he wrote, "at last it became so rapid as to oblige us to come ashore." The rapid waters of the Youghiogheny River attract enthusiasts from all over the world to enjoy their terrifying delight. Adventure-seekers can splash through rapids named Entrance, Cucumber, Camel and Walrus, Dartmouth, Eddy Turn, Railroad, Dimple Rock, Swimmers, Wine in a Bottle, Double Hydraulics, River’s End, Schoolhouse Rock and Bruner Run. These rapids fit any experience level and are open to kayakers, closed-deck canoes and rafts. Four parts of the river include the Middle Yough, the Lower Yough, the Cheat River and the Upper Yough. The Middle Yough is a popular with families and young children. The Lower Yough, the last 7.5 miles, is a great experience for everyone of the age 12 and older. The Cheat River is the “undisputed king of the spring time rafting.” Finally, the Upper Yough is one of the hardest commercially run rivers in North America.

One rapid in particular, Dimple’s Rock, often makes its name in newspapers due to the danger that it can pose to individuals who are brave enough to tackle it. Tim Palmer explains:

Thirty percent of the river slams into a rock on the left shore, then splays 90 degrees to the right to pillow over another rock. White caps and more rocks follow. This rapid was named by some of the first canoeists who scouted the drop and discovered a sunken canoe called ‘Dimples’.

Rafts and kayaks can easily capsize in the treacherous turn— a few have drowned. Several fatalities have been blamed on Dimple’s Rock, however, many believe that pre-existing health conditions have played some role in these deaths. To combat future incidents, Park Manager Doug Hoehn has established a safety focus group. Group members consist of park managers, outfitters and paddlers, the U.S. Corps of Engineers, the PA Fish and Boat Commission and DCNR management from Harrisburg. Safety expert Charlie Walbridge states: “I believe that most people who flip above the rock stay in the pillow and are washed to the right and safety.” However, others suggest that Dimple’s Rock should be removed or blown up. If the rock was blown up, many rafters or kayakers may be “carried towards a number of large undercut rocks on the river left, which would pose new hazards and serious dangers.”

Visit PA Media Room

The Ohiopyle Falls Race is the ultimate event for thrill-seekers. One day a year, the twenty-foot Ohiopyle Falls open to kayakers seeking to take the plunge over the falls’ edge. Since 1999 a large annual festival has celebrated the event, bringing tons of tourists to view the spectacle. However, 2010 saw the introduction of a pilot program that opens the Ohiopyle Falls to kayakers from May to September each year. According to Chuck Parker, kayaking enthusiast, “It can be a really, really safe sport if you do it right.” Since the program’s inception there have been over fourteen thousand runs over the falls with no fatalities.

Pennsylvania conservation agencies are currently battling large oil companies seeking to drill for natural gas beneath the Marcellus Shale deposits in Ohiopyle State Park. Sadly, Pennsylvania only holds twenty percent of the subsurface rights in its state parks— rendering parks helpless to stop much of the drilling. Environmentalists fear the desecration of Ohiopyle’s beauty and the aftereffects of “fracking fluid” a chemical used to fracture shale deposits to obtain natural gas beneath. The chemical is unregulated by the United States or Pennsylvania Governments and can potentially harm wildlife and heavily pollute Ohiopyle’s pristine waterways if used in moderate amounts.

Ohiopyle State Park is found to be a beauty of nature in itself and was established to be re-grown to its fullest potential. Shelby Mitchell accepts the fate of Ohiopyle and states, “This is what Ohiopyle was to be.”

Sources:

- Come to Ohiopyle. <http://www.cometoohiopyle.com/>.

- Erdley, Debra. “Pennsylvania parks seen as vulnerable to Marcellus developers.” Pittsburgh Times-Review. 20 Aug. 2010.

- Forrey, William C. History of Pennsylvania’s State Parks. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Bureau of State Parks, Office of Resources Management, Department of Environmental Resources, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 1984. 43–44, 60.

- Fort Necessity and Historic Shrines of the Redstone Country. Uniontown, PA: Pennsylvania Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 1932.

- Hoffman, Mark. “PA parks named ‘Best in Nation’.” Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. 30 May 2010.

- Kaufman, Edgar Jr. Fallingwater. New York: Abbeville Press.

- National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior. Fort Necessity. 2 June 2010. <http://www.nps.gov/fone/index.htm>.

- Oakley, Amy. Our Pennsylvania: Keys to the Keystone State. New York: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., 1986.

- Palmer, Tim. Youghiogheny, Appalachian. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1984.

- Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Ohiopyle State Park. 1 June 2010. <http://www.dcnr.state.pa.us/stateparks/parks/ohiopyle.aspx>.

- Pickels, Mary. Kayakers take plunge over Ohiopyle falls.” Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. 22 Aug. 2010.

- Walsh, Lawrence. “River Rafting at Ohiopyle.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 25 Apr. 25. DD-1.

- “Western Pennsylvania History.” 13th Historical Tour of the University of Pittsburgh and The Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania to Fort Necessity and Mountain Lake Park 37: 3-4. 1954-1955.

- White Water Rafting. Pamplet. Ohiopyle, PA: White Water Adventurers, Inc., 2010.