At Rockville just above the capitol city, they have thrown across the Susquehanna a four track bridge of monolithic stone seven eighths of a mile long and stepped in graceful arches as enduring as the mountains that look down on the beautiful river. Bridges, like men, have their tables of mortality, but in the expectancy of the life according to American bridges here is a structure to which no limit of years may be assigned; it has been built to last forever.

— Frank H. Spearman, Strategy of the Great Railroads, 1914

All Aboard!” Passengers traveling from New York City to Chicago scurried around Penn Station preparing to board the Broadway Limited of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company (PRR). Porters grabbed the bags of boarding passengers and showed them to their sleeper cars where they would stay during the twenty hour trip to Chicago. Before planes, trains were the primary mode of transportation for American businessmen. The Broadway Limited was one of the most widely used railways for travel from the business centers of the Northeast to the expanding Midwest. Since the round-trip was nearly 1,900 miles, the Broadway attracted passengers by boasting high-speed travel and luxurious sleeper cars.

The Broadway’s interiors looked more like hotel rooms than train cars. There were writing rooms outfitted with bookcases and dark-wooden desks, smoking rooms, barber shops, and dining rooms. In Joe Welsh’s illustrated history of the rail line from 1902 to 1955, Pennsylvania Railroad’s Broadway Limited, a porter describes the sleeper cars to a first-time passenger: “Within it are comfortable sofa seats with arm rests, lights for reading, controls for heating and air conditioning, a fan, wardrobe, shoe locker, luggage rack, and mirror. In one corner is a toilet disguised as a seat with a portable wash basin. At night a pre-made bed can be pulled down from the wall.” This extravagant attention to detail attracted high-paid businessmen to Broadway’s train ticket booths.

The Broadway Limited was an icon of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s golden years. Its success was enabled by large infrastructure projects completed by the PRR during the first decade of the 20th century—such as the Rockville Bridge, still the longest stone arch bridge ever constructed, spanning the Susquehanna and heading west at Rockville.

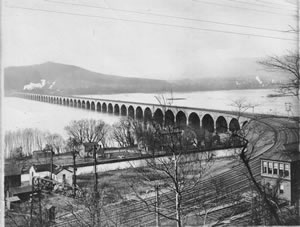

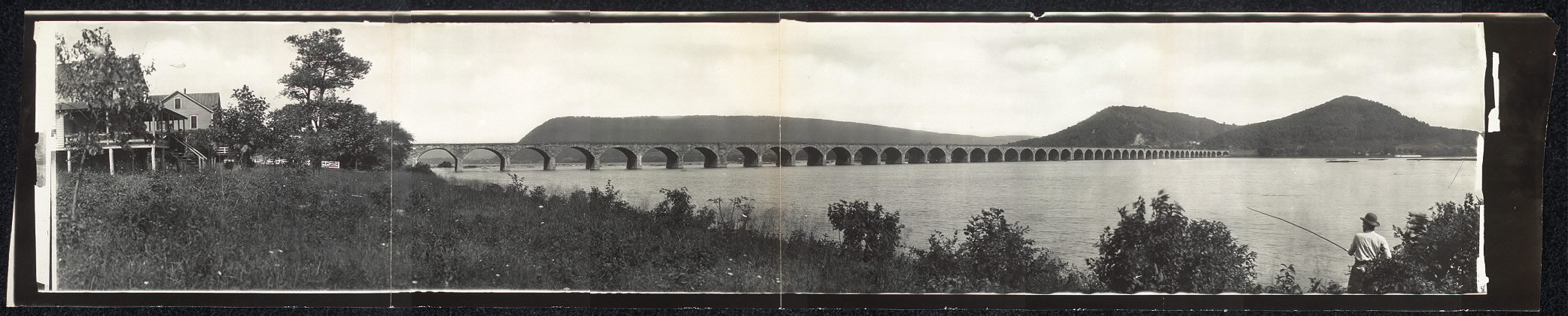

At the Marysville exit off U.S. highway 15, on the west bank of the Susquehanna River, a community sign reads: “Welcome to Marysville, Home of the Rockville Bridge.” Opening on March 30, 1902, the Rockville Bridge was the most important and expensive undertaking of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. Just north of the Enola train yards (once the largest train yard in the world), the Rockville Bridge is a National Historic Landmark and is currently used by Norfolk Southern and Amtrak railways.

The Rockville Bridge is the successor to two previous bridges in the same location. The first was a single-track wooden bridge, completed in 1849. This bridge survived a fire in 1868, but by the late 1870s, as a report on the modern bridge to the National Register of Historic Places program had put it, it was “not large enough for the enormous traffic now being handled” at the apex of the Industrial Revolution. The original bridge was replaced by a double-track iron bridge in 1877 which was placed on the piers remaining from the wooden bridge. But with the twentieth century right around the corner, rail travel continued to steer American industrial growth and trains and their cargo became heavier. Iron truss bridges became infamous for tragic structural failures and began to be replaced. [Photos 2 & 3] The Marysville iron truss bridge began to limit the capacity of one of the PRR’s most profitable lines, and, thus, was replaced by the current bridge at the turn of the century.

The current Rockville Bridge was built in an effort by the Pennsylvania Railroad Company to provide more durable structures along its rail lines. Alexander J. Cassatt, the president of the PRR during the early 1900’s, is best known for vastly increasing rail capacity by laying more mainline tracks, expanding rail yards, and building bigger passenger terminals. He is also known for building large, durable stone arch masonry bridges during the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. Chief Engineer William H. Brown implemented Cassatt’s plan by designing and constructing two or three heavy-duty stone arch masonry bridges each year from 1900-1906. He built enough such bridges to earn the nickname of the railroad’s “Stoneman.”

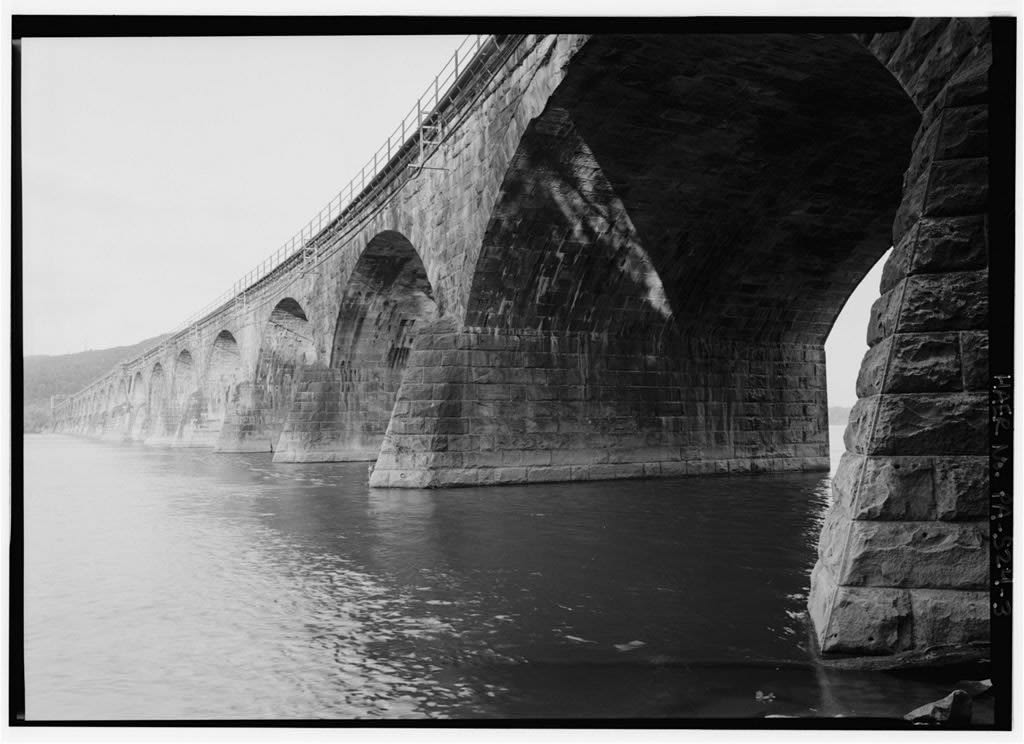

Resembling the aqueducts of the Roman Empire, the Rockville Bridge is truly a spectacle to behold. Spanning 3,380 feet, or nearly nine and a half football fields, it boasts forty-eight arches of seventy-foot span each. The bridge is concrete to the core and surrounded by sandstone mined in Clearfield County. Its construction required 220,000 tons of stone and 150,000 cubic yards of concrete—a volume equivalent to nearly forty-six Olympic size swimming pools. As many as 300 stonemasons, many of them Italian immigrants who relocated from Curwensville in Clearfield County, worked on the sandstone rock facade, perhaps the major aesthetic appeal of the landmark.

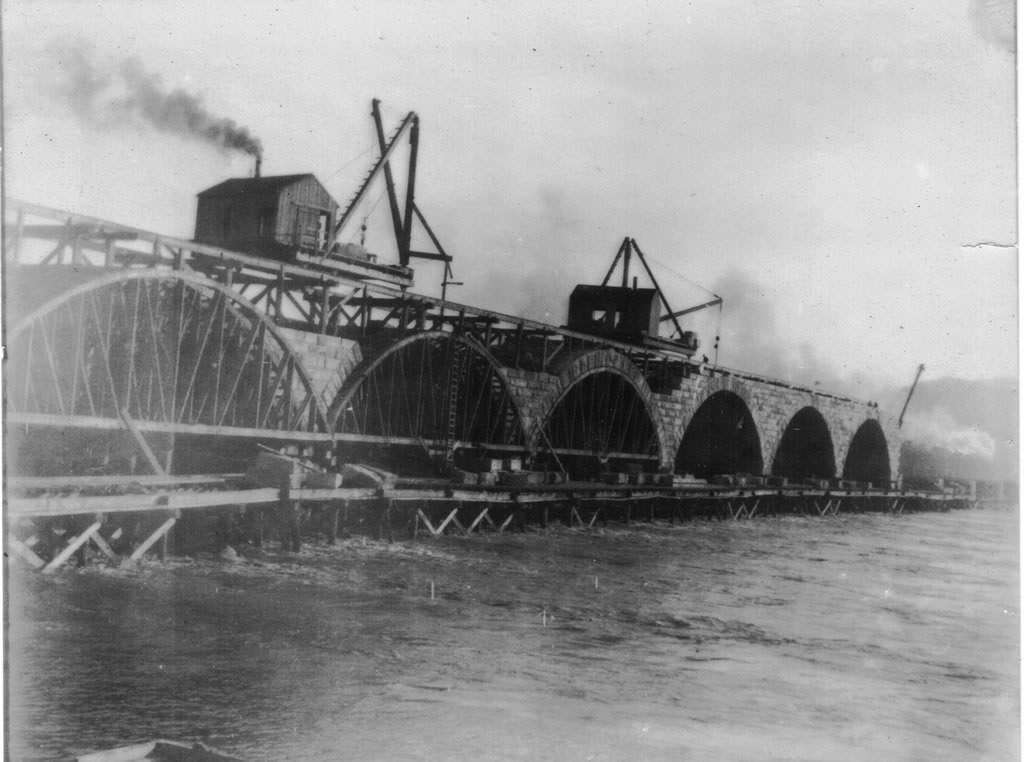

The construction of the bridge took nearly two years. Beginning in 1900, two Philadelphia contracting companies began laying the groundwork for the bridge at opposite ends of the Susquehanna: Drake & Stratton on the east end, H.S. Kerbaugh on the west. Although the chosen location of the 1849 wooden bridge had been criticized for the breadth of the river and sharp turns required on both of the river’s banks, the shallow water in the Susquehanna provided an opportunity to hasten the construction of the bridge in 1900.

The water was unusually low in the Susquehanna River in the summer of 1900. The contractors took advantage of the low water and constructed all of the piers at once and as many of the arches as possible during the construction season. The first step in each arch’s construction was a wooden scaffolding, also known as falsework. The falsework was used as a form, over which voussoirs, the stones of the arch were set in place. The middle stone was called the keystone. The wooden falsework alone would not withstand a Pennsylvania winter, so the construction crew had to complete all the stonework for the arches during one construction season, in 1900. [Photo 4]

The design of the arch was ideal for carrying heavy loads over large spans. A bridge’s piers must be able to support applied loads—the trains that run across its tracks, as well as the weight of the bridge itself. The arch enables the bridge to handle heavier cargo by transferring the applied load and self-weight to compressive stresses centered in the arch’s keystone. The stone masonry arch bridge was an ideal design to handle the ever increasing weight in cargo the PRR was shipping across its rail lines through Harrisburg.

Throughout its more than one-hundred year history, the Rockville Bridge has proven to be durable and reliable. The bridge was a known military target during both World Wars, and armed guards stood watch at both its banks. Rockville Bridge survived a flood in 1936. In 1972, the 28-arch Shocks Mill Bridge, located only thirty miles downstream from Rockville, was washed away in tropical storm Agnes—Rockville withstood that as well.

Repeated freeze and thaw events that occur in Pennsylvania put some wear and tear on Rockville Bridge. In 1997, some of its stones were forced out of line, causing a passing train to topple over the bridge, and its tons of stone, rails, ties, and four 100 ton rail cars filled with coal to fall into the Susquehanna River. The repairs and environmental cleanup totaled 100 million dollars. But despite minor repairs, the structure of the bridge has remained intact for over one hundred years.

The Rockville Bridge is a historical symbol and reminder of the economic boom that was driven by the railroad. Although a twenty hour ride on a luxurious sleeper car is no longer the desired transportation method, we still use railroads to ship freight throughout the country. The bridge that was described as “built to last forever” still spans the Susquehanna. Nearly 110 years after its completion, the Rockville Bridge continues to be a serviceable and durable bridge to this day. The Rockville Bridge, said to be “built to last forever,” hasn’t let us down yet.

The Center wishes to thank Gregg L. Sloan for his assistance illustrating this article.

Sources:

- Boothby, Thomas E., and Arthur K. Anderson. “The Masonry Arch Reconsidered.” Journal of Architectural Engineering 1.1 (1995): 25-36.

- Cupper, Dan. Rockville Bridge- Rails Across the Susquehanna. Halifax, PA: Withers, 2002.

- Hain, H. H. History of Perry County, Pennsylvania. Harrisburg: Hain-Moore, 1922.

- Jackson, Donald C. Great American Bridges & Dams. Washington, DC: Preservation Press, 1988.

- Lesley, Robert W. History of the Portland Cement Industry in the United States. Philadelphia: American Cement Company, 1900.

- Arnold, Walter S. “Still Practical.” Rev. of Modern Practical Masonry by Edmund George Warland. Traditional Building Apr. 2007. 9 Apr. 2010 <http://www.traditional-building.com/Previous-Issues-07/AprilBR07Practica....

- “Pennsylvania Railroad, Rockville Bridge, Spanning the Susquehanna River, North of I-81 Bridge, Rockville, Dauphin County, PA.” Historic American Engineering Record (Library of Congress) (1999): 1-6. <http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.pa3731>.

- “Rockville Bridge: Marker Details.” ExplorePAHistory.com. 31 Mar. 2010 <http://explorepahistory.com/hmarker.php?markerId=638>.

- Spearman, Frank H. The Strategy of Great Railroads. New York: Charles Scribner’s Son, 1914.

- Treese, Lorrett. Railroads of Pennsylvania: Fragments of the Past in the Keystone Landscape. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole, 2003.

- Welsh, Joe. Pennsylvania Railroad’s Broadway Limited. St. Paul: MBI Company, 2006.