Traveling long distances before the early 20th century was no easy task. Despite the invention of automobiles, travelling was still a long and arduous process. Anyone who wanted to travel the 3,400 miles from coast to coast across the United States would have to have taken between 60 and 90 days to complete the journey. Travel was usually done on dirt roads that were better-suited for horses and carts than for cars, as paved roads were practically nonexistent in the early days of automobiles. There were no direct paths from one side of the United States to the other, though there were seven “trails” that could be taken across the continent. It was possible to travel long distances by train, but this option was subject to train schedules and railway routes.

That all changed in 1913 with the creation of the Lincoln Highway. The first road of its kind, the Lincoln Highway spanned the entire continental United States from New York City to San Francisco. It wound its way through 13 states, giving travelers a uniform route from one side of the country to the other.

The idea of a road that spanned the entire United States was conceived by Carl Fisher, who, together with some other businessmen, established the Lincoln Highway Association on July 1, 1913. The highway was not the first major project Fisher worked on. A successful entrepreneur who focused on automobiles, Fisher’s Prest-O-Lite Company made headlights that were used on most early automobiles, which made him rich. He had also helped develop the Indianapolis Speedway a few years before starting work on the Lincoln Highway, and he would go on to create Miami Beach a few years after. Throughout his life, Fisher was involved in projects that had big impacts on society. He had the creativity, financial ability, and determination needed to suggest that building a road as massive as the Lincoln Highway was possible, despite how overwhelming the idea seemed at first.

Fisher’s cross-continental highway was mapped out and dedicated to President Abraham Lincoln, one of Fisher’s heroes, in 1913. It was the first national memorial to President Lincoln, as the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. would not be built until 1922. Thanks to the Lincoln Highway, a cross-country road trip could be accomplished in only 30 days. According to H. C. Ostermann, the Field Secretary of the Lincoln Highway Association, “the entire expense of a car and four passengers from New York to San Francisco...via the Lincoln Highway, should not at any time exceed $5.00 a day per passenger under normal conditions.” Ostermann’s calculations included money for “gasoline, oil, and all provisions.”

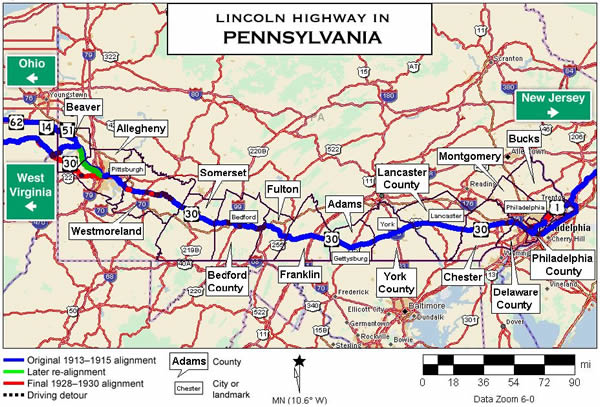

While constructing the Lincoln Highway, many already-existing roads served as bases for the route to follow. For this reason, the highway was mapped out and completed rather quickly. According to Dr. E. Kenneth Vey, “in Pennsylvania, the greater part of the roadway utilized pre-existing roads linking up those roads for practical application and economy, paving them with gravel and macadam.” In the west, the highway followed the Forbes Road, an old route built by Brigadier General John Forbes in 1758 to keep supply lines running during the Seven Years’ War. In the east, the highway was based on the Lancaster Turnpike, which, upon its completion in 1794, was the nation’s first toll road and was “praised as the finest highway of its day.”

In Pennsylvania, the Lincoln Highway stretches for 292.2 miles from west of Pittsburgh to Philadelphia. Traffic laws of the time originally kept motorists driving at a cautious speed limit of 25 miles per hour--and there was no fast lane! The speed limit was even lower in many small towns, even going as low as 12 miles per hour, and it was often strictly enforced. The Complete Official Road Guide of the Lincoln Highway, a guidebook released every few years by the Lincoln Highway Association, gave its readers a town-by-town description of what lay in store for travelers, including speed limits for each individual area. Road conditions and types were also listed, with such labels as “paved,” “dirt roads,” and “gravel.” Conditions were listed as “good,” “fair,” or “poor,” and sometimes included notes like “bad in wet weather.” The book also offered tips on how to handle one’s car on certain stretches of road or different types of terrain.

Road conditions and driving tips were not the only notes the guidebook gave its readers; it also told them about places of interest they might want to stop to explore, and also described the scenery of the more beautiful stretches of the highway. The following excerpt gives a good example of how the guidebook combined notes on the road with notes on the scenery:

The Lincoln Highway is of bituminous macadam or brick the entire distance from Bedford to Pittsburg [sic]. The country traversed is quite hilly but the grades are easy and the scenery is magnificent. Seventeen miles west of Bedford the tourist will encounter a spot known as Grand View from which point one is treated to one of the most magnificent of scenic views on the American continent--in the foreground the pastoral beauty of Pennsylvania’s most fertile and highly cultivated region, the rolling hills of Maryland in the distance and far beyond a glimpse of the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia.

Travelers were able to enjoy beautiful scenery throughout the Pennsylvania stretch of the highway, often from high elevations in the Allegheny Mountains. Frank B. McClain, who contributed to one of the first Lincoln Highway road guides in 1920, said that the highway was “one of the most scenic drives to be found in the state of Pennsylvania or the entire east coast.” Many other people shared his opinion, and the beautiful drive added to the highway’s appeal to adventurers wealthy enough to own an automobile.

There was a downside to the highway in Pennsylvania, however. In the official guidebook, McClain claimed that “tolls are the bane of the Pennsylvania road system.” The guidebook gave a listing of tolls along the highway, and McClain went on to assure readers that “every endeavor is being made to eradicate them.”

The Lincoln Highway was home to a number of attractions and interesting places for its travelers to explore. In Pennsylvania, tourists had many interesting and historical stops to choose from, including Valley Forge and Gettysburg. The highway also boasted many examples of novelty architecture--which, as explained by Debra Jane Seltzer, is a type of architecture that has “buildings that imitate or look like something else (giant food, animals, people, objects, etc).” In the early 20th century, business owners used novelty architecture to make their businesses stand out and attract more customers.

Perhaps the most eye-catching piece of novelty architecture on the Lincoln Highway was the S.S. Grand View Ship Hotel. This famous ship-shaped hotel perched on the edge of a cliff in Bedford County, at the aforementioned Grand View. According to the official guidebook, Grand View was “one of the finest views in the Alleghany [sic] Mountains.” The Ship Hotel offered its guests a view of “63 miles...three states and seven counties.” It was created in 1932 by Herbert Paulson and his rampant imagination. According to his granddaughter Clara Gardner, who was born and raised in the Ship Hotel, “he made it look like a ship because the fog in the valley looked like the sea.” The hotel attracted all sorts of people, from everyday tourists to celebrities. Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, Greta Garbo, and Pennsylvania’s very own Western film star, Tom Mix, and his horse, Tony, can all be counted among the Ship Hotel’s patrons.

With the creation of newer roads, the Lincoln Highway became less traveled and the Ship Hotel began to lose business. In 1978, it was bought by Jack and Mary Loya, who covered it in wood to make it look like Noah’s ark and added a petting zoo. Their attempts to attract business failed, and the building sat unused and decaying for years. In the late ‘90s, the Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor, a preservationist group, offered to buy the building from the Loyas for the appraised price of less than $50,000. The Loyas demanded $900,000. The standoff lasted until October 26, 2001, when the dilapidated hotel suddenly caught fire and burned to the ground.

Another beloved attraction on the Lincoln Highway is the Haines Shoe House. A giant shoe-shaped building, the Shoe House was built in 1948 in Hellam, York County. It originally served as a self-advertising shoe store for owner Mahlon Haines, who was known as the “Shoe Wizard” and “invited elderly couples and honeymooners to stay at no cost if they lived in a town with a Haines shoe store.” Today, the building offers tours as well as ice cream to its visitors.

Yet another famous piece of novelty architecture found on the Lincoln Highway is the Coffee Pot. A giant building shaped like a coffee pot, it opened in 1927 in Bedford and was originally a restaurant before it was transformed into a bus station, and then a bar. It was a popular place to socialize and many people hold special memories of it. Popular Lincoln Highway artist Keven Kutz recalls, “I had painted the Coffee Pot in Bedford six times before I got the nerve to go inside. A few years later, I met my daughter’s mother there.” Kutz also had the opportunity to help paint the lettering on the exterior of the Coffee Pot when it was restored by the Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor in 2003.

The Lincoln Highway sparked an American road revolution, inspiring the construction of similar roads across the country. In Pennsylvania, other long-distance roads began to form when people saw the popularity and economic benefits enjoyed by the Lincoln Highway. Brian Butko, a Lincoln Highway enthusiast, points out that “State maps from the early 1920s show almost 50 named highways.” Within a mere seven years of the Lincoln Highway’s completion in 1913, almost 50 other named highways had popped up. With support from the State Highway Department, donations, and eager Americans with adventurous spirits, Pennsylvania’s road system erupted.

Pennsylvania was not the only state whose transportation routes benefited from the Lincoln Highway, however. According to the Federal Highway Administration, “one of the Lincoln Highway’s greatest contributions to future highway development occurred in 1919, when the U.S. Army undertook its first transcontinental motor convoy.” The convoy was meant to show the need for better highways and Federal aid to help maintain them. One young officer who took part in the convoy was Lt. Colonel Dwight David Eisenhower, future president of the United States. Eisenhower’s experience on the Lincoln Highway and his appreciation of Germany’s cross-country Autobahn in World War II caused him to support the creation of what is now called the Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways—or, more familiarly, the Interstate Highway System--in the 1950s.

With the creation of the Interstate System and the Pennsylvania Turnpike, the Lincoln Highway was assigned the new designation of U.S. Route 30. No longer the only cross-continental highway, it now had competition from other routes, especially U.S. Route 80, which followed the same basic path as the Lincoln Highway but in a much straighter fashion. With competition from the Pennsylvania Turnpike and Route 80, the amount of traveling done on the Lincoln Highway declined. Drivers preferred the newer, faster roads to the old cross-continental highway. Though Carl Fisher died in 1939, long before the Interstate System was created, his entrepreneurial nature would probably have prevented him from mourning the Lincoln Highway’s decline. In 1938, during the highway’s 25th anniversary, he sent a message to NBC radio for a nationwide broadcast. In it, he said that the Lincoln Highway had “accomplished its primary purpose, that of providing an object lesson to show the possibility in highway transportation and the importance of a unified, safe, and economical system of roads.” He also added, “Now I believe the country is at the beginning of another new era in highway building (that will) create a system of roads far beyond the dreams of the Lincoln Highway founders.”

Still, the Lincoln Highway remains beloved by many people and has a sizable following of fans. Brian Butko, a noted author, has written many books about the Lincoln Highway. Artist Kevin Kutz is famous for his many paintings of scenes that can be found along the highway, including well-known architecture and natural Pennsylvania scenery.

A number of groups and associations have been founded to maintain the old highway and what remains of its attractions. In Pennsylvania, the state works to preserve the highway by sponsoring the Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor, one of twelve preservationist groups that protect Pennsylvania’s historic heritage. The LHHC works tirelessly to preserve, restore, and promote pieces of the highway’s past, such as the Coffee Pot and the Shoe House, before these irreplaceable structures go the way of the S.S. Grand View Ship Hotel. Without the efforts of the LHHC, much of the highway—and with it, an important part of Pennsylvania’s cultural heritage—would be lost.

The Lincoln Highway may no longer be the only cross-country road in the United States, but its still has many fans, and its legacy lives on in the Interstate System. Carl Fisher and the Lincoln Highway Association showed that fast, easy, and fun cross-country travel was indeed possible, and the Lincoln Highway paved the way for an even bigger and faster highway system that helped bring the country even closer together. Before 1913, traveling across the country was a slow and arduous task, and not easy to do with a car. After the creation of the Lincoln Highway, however, the other side of the continent did not seem so far away after all.

Sources:

- Butko, Brian. Books by Brian Butko: Fun Stuff Taken Seriously. 2000. 4 May 2011. <http://www.brianbutko.com/>.

- Butko, Brian. Greetings from the Lincoln Highway: America’s first coast-to-coast road. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2005.

- Butko, Brian. The Lincoln Highway: Pennsylvania Traveler’s Guide. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1996.

- Gibb, Tom. “The Ship Sails Choppy Seas $900,000 Price Tag Might Sink Old Route 30 Hotel That Is Dying Of Decay.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 15 Nov. 1998: B-2.

- Kutz, Kevin, Brian Butko, and Mary Thomas. Kevin Kutz’s Lincoln highway. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2006.

- Kutz, Kevin. Kevin Kutz Art. 2009. 4 May 2011. <http://www.kevinkutzart.com/>.

- Lowry, Patricia. “Dream Boat - The Ship Hotel Has Sailed, But A Jaunty New Book Honors Its History And Heyday.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 12 Apr. 2010: C-1.

- Ohio Lincoln Historic Byway. “What is the Lincoln Highway.” Ohio Lincoln Historic Byway. 2009. 3 May 2011. <http://www.olhhc.org/index.php/information/what-is-the-lincoln-highway>.

- Seltzer, Debra Jane. Roadside Architecture. 2000. 3 Apr. 2011. <http://www.agilitynut.com/roadside.html>.

- The Lincoln Highway Association. The Complete Official Road Guide of the Lincoln Highway, 3rd Edition. Detroit: The Lincoln Highway Association, 1918.

- The Lincoln Highway Association. The Lincoln Highway: The Story of a Crusade That Made Transportation History. New York: Dodd, Mead & company, 1935.

- The Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor. The Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor. 2009. 4 May 2011. <http://www.lhhc.org/>.

- The Lincoln Highway Tuscarora Summit to Rays Hill. Lincoln Highway Home Page. Web. 20 May 2010. <http://roadsidephotos.sabr.org/LH/centpenn03.htm>.

- United States. Department of Transportation. Federal Highway Administration. “The Lincoln Highway.” Highway History. 7 Apr. 2011. 4 May 2011. <http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/lincoln.cfm>.

- Vey, Dr. E. Kenneth. “Lincoln Highway.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 19 Oct. 2006: F-7.

- WITF, Inc. ExplorePAHistory.com. 2010. 3 May 2011. <http://explorepahistory.com/index.php>.