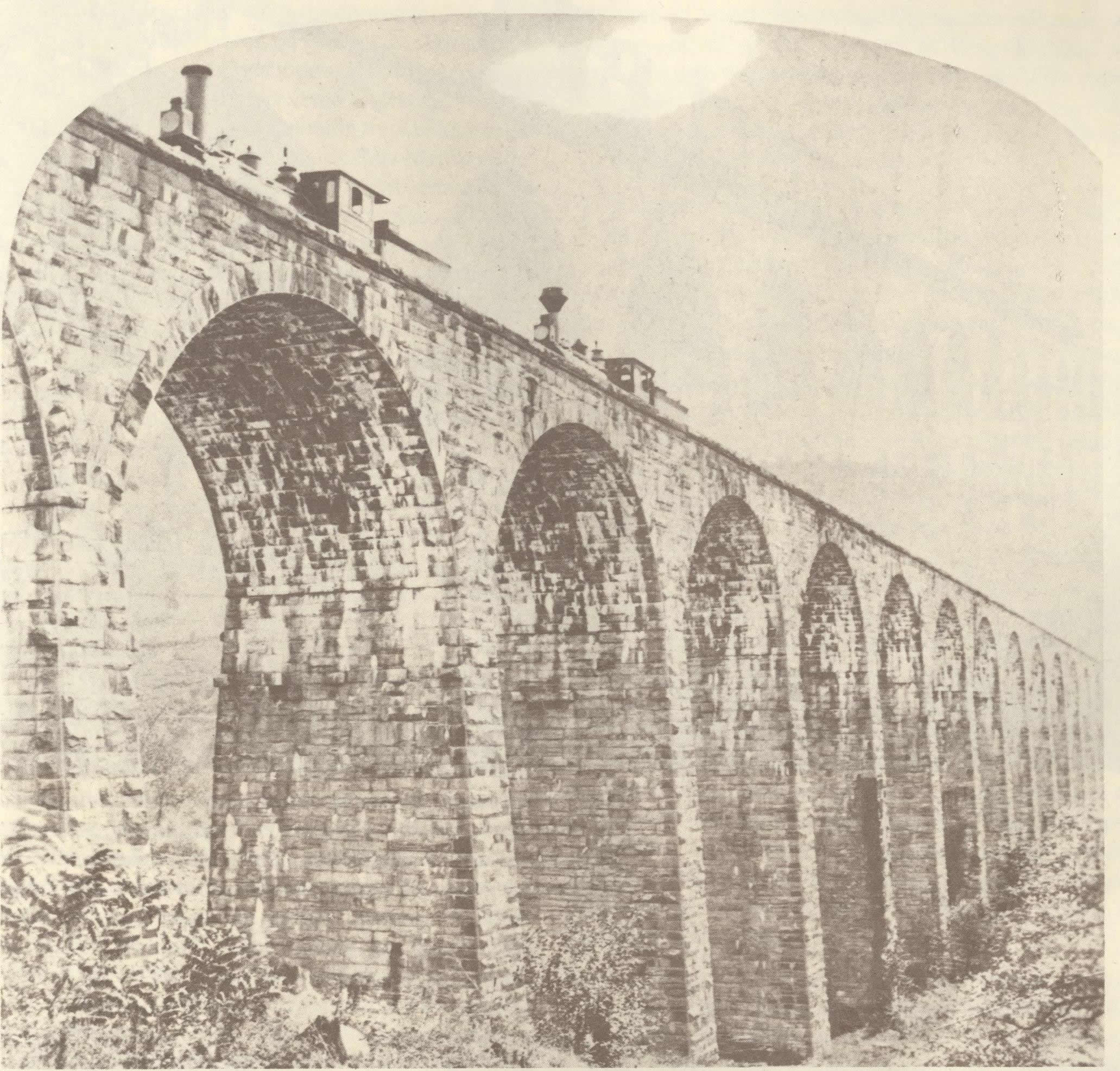

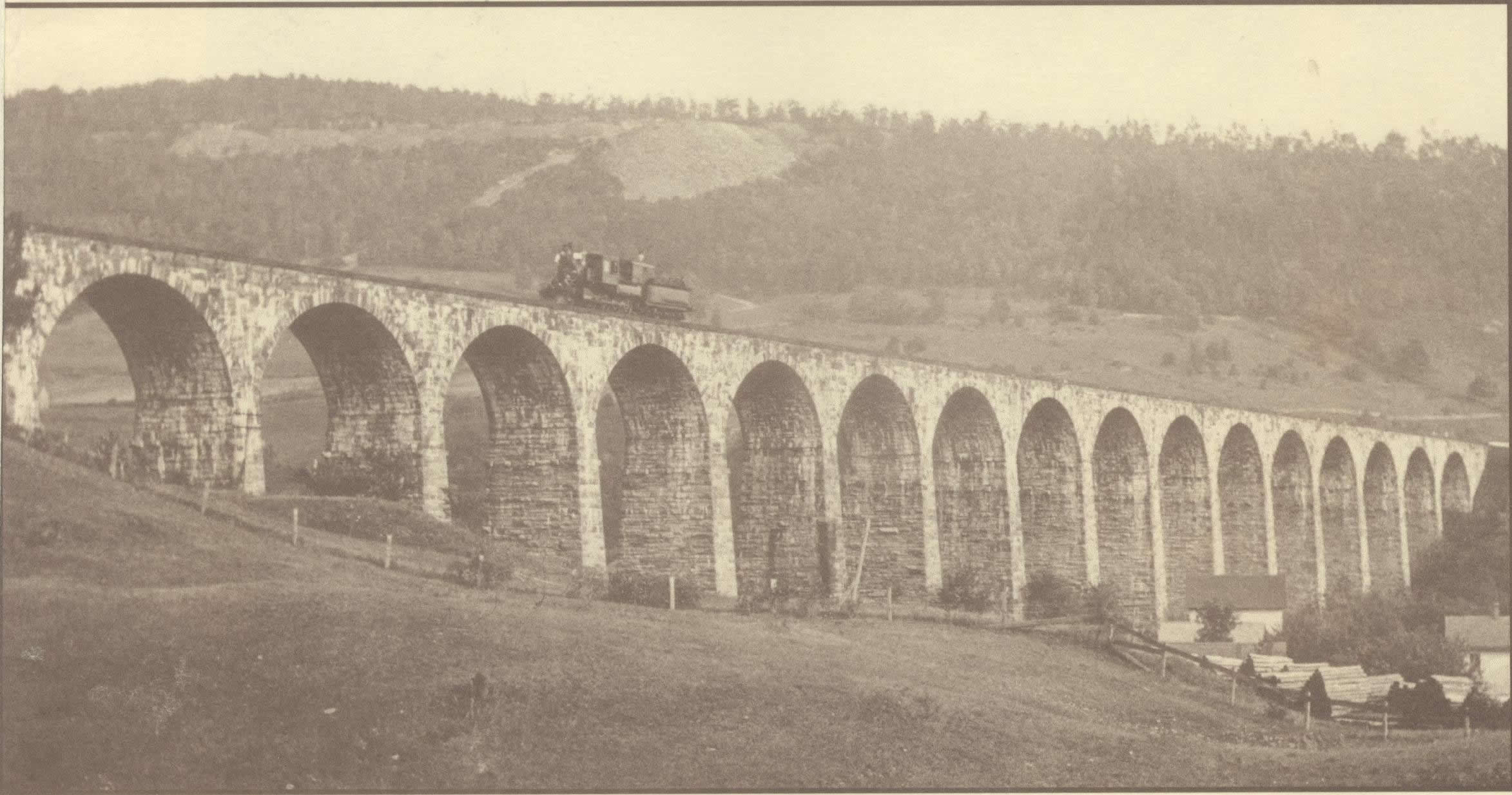

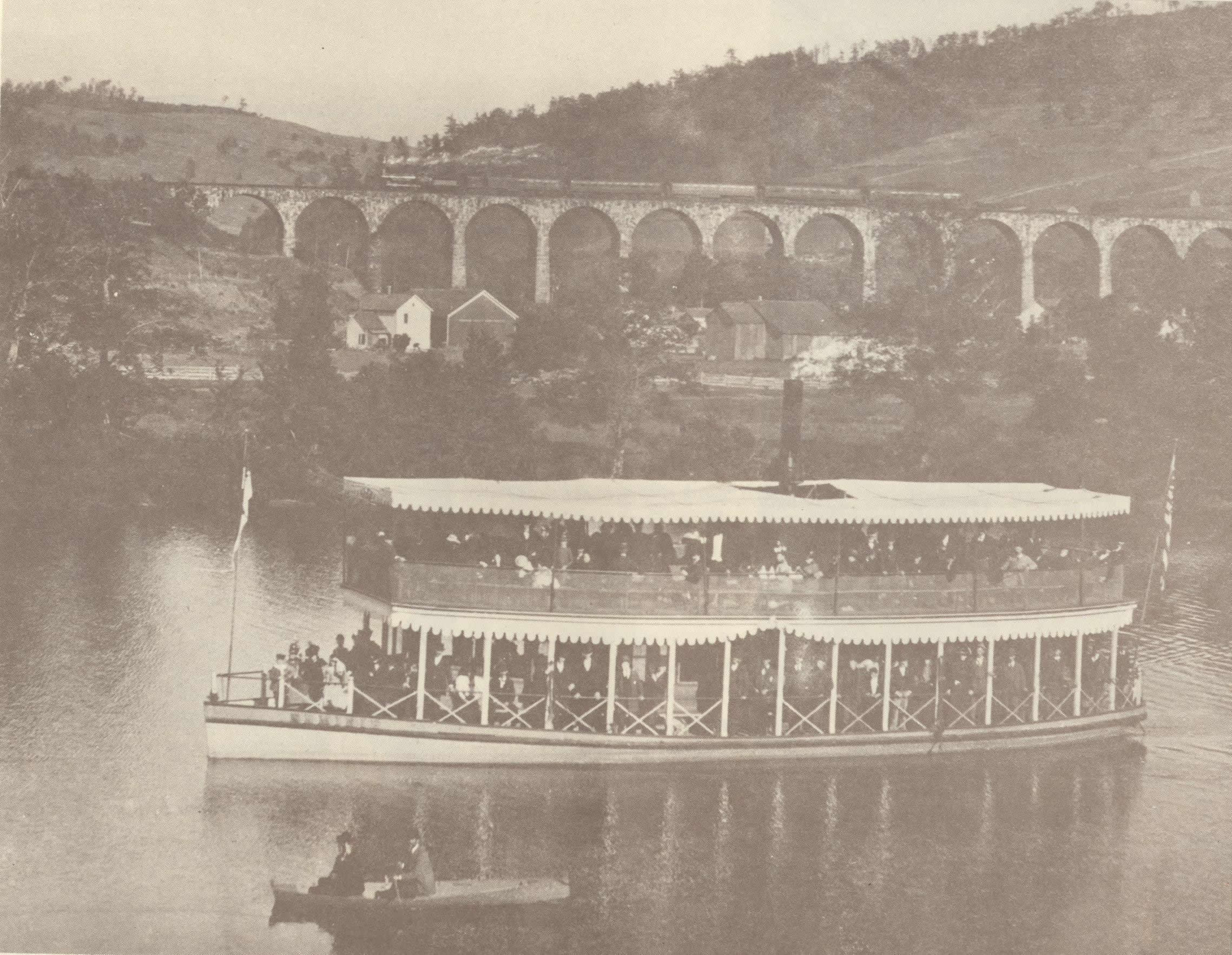

Joining two hillsides of the Starrucca Valley in Northeastern Pennsylvania, the Starrucca Viaduct stands. Gazing westward from the steel ribbon it supports, one sees the Susquehanna River meandering through rolling hillsides and country fields dotted with houses. Unlike so many other great bridges throughout history, the Starrucca Viaduct inhabits a landscape that is largely unchanged from when it was constructed. So too has the viaduct itself been unchanged. Built in 1847-48, it endures today, almost exactly the way it was over 150 years ago.

But to say that the Starrucca Viaduct is a beautiful bridge in a picturesque landscape is not nearly enough. In its stones and mortar, its arches and pillars, and through the people who helped conceive it, lies a great story to be told. This story begins with the New York and Erie Railroad.

Welcome to nineteenth-century America. It was a time of great growth and optimism for a struggling young country. But life was still slow and labor hard in many ways. Most travel was done by wagons with teams of horses or mules and the only means of transporting goods or people in great quantity was by river or canal. A giant of transportation in its time, the Erie Canal brought wealth and population growth to the lands it connected, and with it, much political power to ensure its continued well-being. These were the forces that the New York and Erie faced and, ultimately, surmounted.

Nothing more than an idea at the time, the New York and Erie was the imagining of a man by the name of William C. Redfield. Edward Hungerford’s Men of Erie recalls Redfield and the chain of events that led to the Erie. He developed a zeal for the idea of a railroad from the Hudson River directly to upstate New York and across the southern tier counties to the Great Lakes. This plan he put into print, which soon gained much attention, and most importantly, from a man named Eleazar Lord.

After many political machinations, the New York and Erie, with its president Eleazar Lord, succeeded in gaining state approval in 1832 and ground was broken in the small village of Deposit, New York on November 7, 1835.

And so the construction of the New York and Erie began. From Piermont on the Hudson River to Dunkirk on Lake Erie, the railroad would stretch 483 miles. Contrary to what might be expected, construction took place at various points along the route and not at all in a continuous fashion.

Eleazar Lord and others along the way had a very particular vision of the path the railroad was to take, and in order to see that it not be altered, chose locations for construction that were well away from strongholds of their political opponents. By building sections at different points, it also ensured that the railroad did not deviate from its intended path significantly. But deviations were necessary when it came to the track of rails through the Delaware and Susquehanna River Valleys.

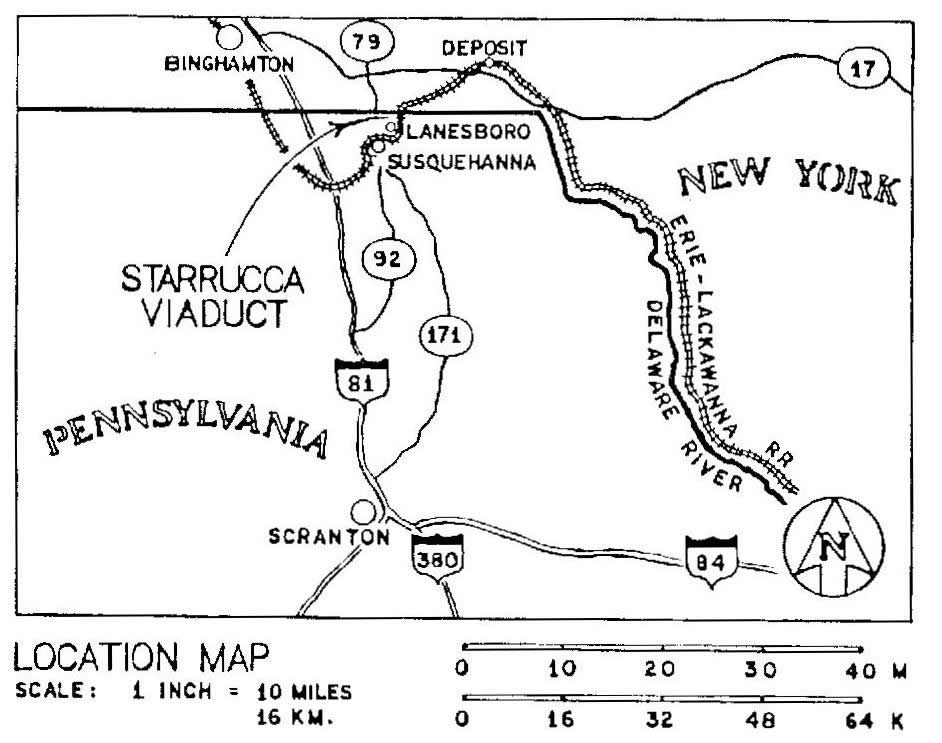

To fulfill its charter, the New York and Erie needed to complete its line from Piermont (on the Hudson) to Binghamton, New York by 1848. To do this, the only feasible option meant diverting the route into Pennsylvania two times to avoid areas that would have been prohibitively expensive to cross in New York. For the privilege of using its land, the New York and Erie agreed to pay Pennsylvania $10,000 a year, but by 1846, right-of-way for both crossings had been given by the Pennsylvania Legislature. It is in the second and last of these crossings that the Starrucca Viaduct lies.

Spanning the Starrucca Creek and the valley it is in was no easy task. No matter how it was to be done, the New York and Erie needed to gather huge amounts of materials and labor. Initially, a massive fill was considered. A fill quite literally means dumping tons of soil into the valley to raise the ground to track level. However, this idea was abandoned after determining that it would cost more than a bridge. So finally, a stone viaduct was to be the solution.

According to William S. Young, the bridge’s leading authority and author of Starrucca: The Bridge of Stone, Julius W. Adams designed and proposed the plans for the stone bridge, and it was Adams who selected his brother-in-law, James P. Kirkwood, to build the bridge. Young also recalls much of the history of these two men.

Produced by Company Forces, 1959.

Julius Walker Adams grew up in a well-connected family tied to some of the greats of military and civil engineers in America at the time. He worked with some of the family’s railroad enterprises, meeting Kirkwood along the way. Kirkwood had been working for Adams’ uncles on other early railroad projects, so when Adams sought an engineer to be in charge of construction, Kirkwood was an obvious choice. Some dialogue between Adams and Kirkwood is remembered in Between the Ocean and the Lakes: Story of Erie, by Edward Harold Mott. With deadlines were fast approaching for the railroad, New York and Erie’s representatives asked Adams who could build the viaduct. To this Adams replied, “I know of no one who can do it unless it is Kirkwood.” And when asked whether he was up to the task, Kirkwood replied “I can build that viaduct in time, provided you don’t care how much it cost.” Fortunately for Kirkwood, the New York and Erie didn’t care.

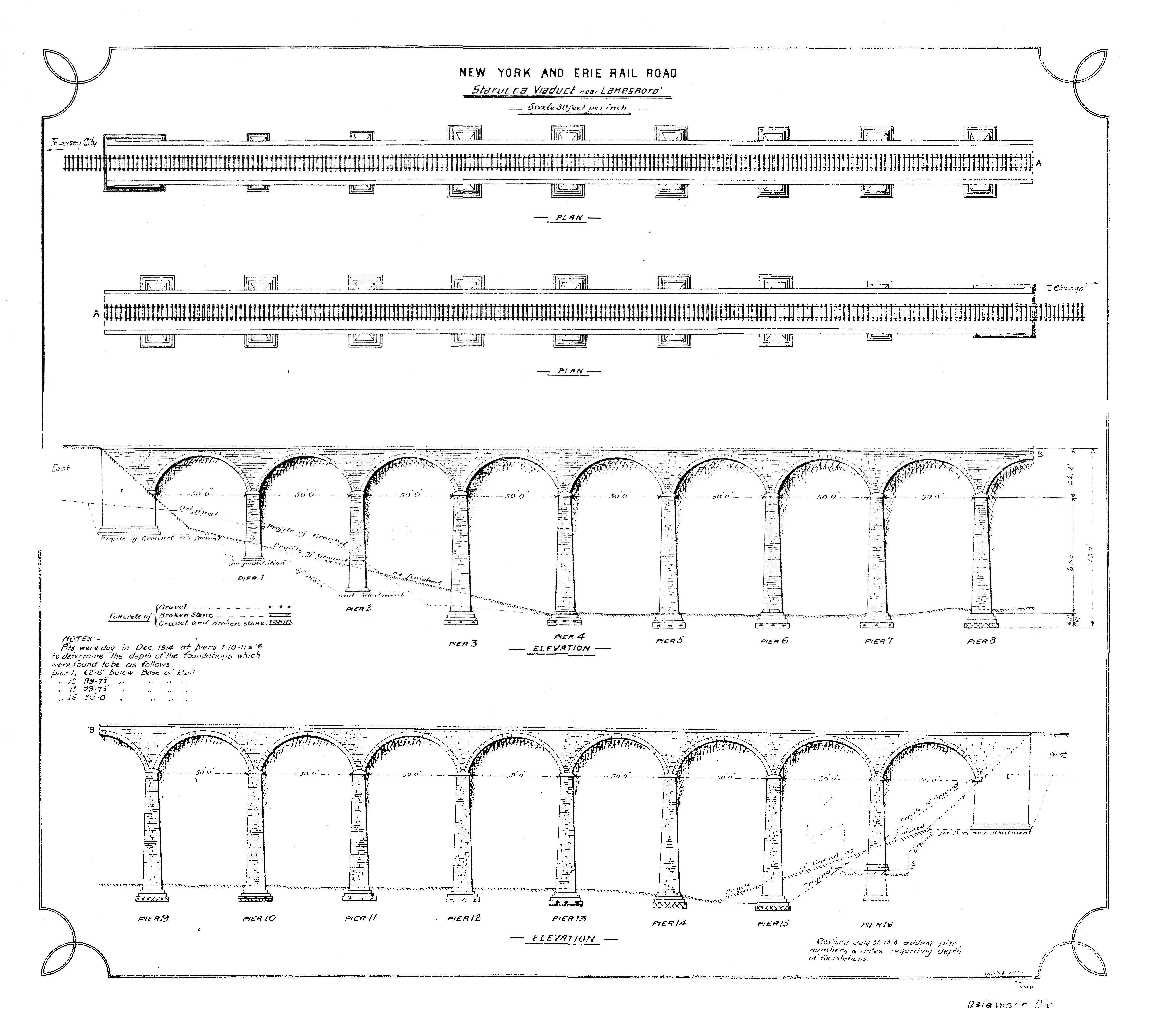

Young’s Starrucca: The Bridge of Stone offers more details of the bridge and its construction. At 1040 feet in length, 25 feet wide at the deck level, and 90 to 100 feet high, the Starrucca Viaduct was the largest and most expensive stone arch bridge built in America at the time. In 1850, Kirkwood determined the total net cost of the bridge to be $316,770. Built almost entirely from locally quarried Pennsylvania bluestone that varied from 9 to 18 inches thick, a makeshift railroad hauled the stone from the quarry, four miles up the Starrucca Creek, to the construction site. Wagons transported some stone from another neighboring quarry as well. The pier footings, dug 6 to 9 feet deep into the valley floor, were poured concrete, and are among the earliest uses of concrete as a structural building material in American bridges. The only other exception to bluestone use was three brick spandrel arches, or interior walls that run parallel to the tracks to help distribute the load of a train to the stone arches and piers.

The labor required for the bridge drew men from all of the surrounding area, totaling about 800. Because of the rush to get the railroad to Binghamton by the time the charter demanded, labor, supplies, and all necessary provisions were amply provided.

One example of this ample supply is the falsework needed to construct the stone arches. Falsework is wooden timber frames that are built between each pier to support the stone arches as they are being built. Normally, only one set is needed. Arches would be constructed one at a time, and after the completion of each arch, the wooden framing would be disassembled and then reassembled for the next arch. But because this would take up all too valuable time, each of the 17 arches had its own set of falsework made. More of the building process is remembered by Hosea M. Benson, a civil war veteran, who was eleven years old at the time of the project. The Montrose Independent first printed his remembrances in 1931, and the following is taken from them.

“There was great commotion among the people when the first report came that there was to be a railroad built from New York to Lake Erie, there to connect with boats for the far west. It was in the year 1845. It was some time before the surveyors got up to the Gulf Summit [,] Cascade and to Lanesboro…My father and I visited the scenes and work of the railroad building very often, which was very interesting and exciting to us all…

The stone was cut and numbered and loaded on the stone cars drawn by horses and mules over the piers and were unloaded by derricks down on the piers. They drilled two holes in the large stone, about two feet apart. They had a short chain with ring in center and short plugs on each end. They would stick these plugs in the holes with the derrick, hook in the ring and let them down on the piers where they were fitted to go. The stone was … marked with black paint. The masons on the piers knew where to lay [it].

When the piers were up to the track they built another section of false-work and so continued to raise the track over the piers until the work was done. When the piers were high enough for the arches, they left projecting a row of stone to set the wood arches to [,] to lay the stone on. They were now one hundred feet from the ground and every pier was fastened just the same and stands in a perfect row, just the same as was built…

When the bridge was completed it was a wonderful view to behold, to see that bridge with the false-work of timbers filling the space between the piers from the ground to the arches… The contract [to remove the falsework] was let to a man by the name of Purdy. He built a boarding house, or shanty like, very long on the ground, where the school house now stands, boarding many of his men and paid them $1.00 a day… He soon had a lot of men who were not afraid to work on that dangerous job. A number… went from Jackson. My father was one…” —Hosea M. Benson, November 24, 1931

When all was said and done, the bridge consisted of 21,259 cubic yards of masonry. The concrete footings for the piers were made from Rosendale cement, famous for its use in the Brooklyn Bridge and Statue of Liberty, among other structures. The piers, originally intended to be hollow, were built solid after bluestone of substantial thickness was found to be available. Railings, although typical of many bridges of the era, were never present by any account. Each arch spanned a diameter of 50 feet, and the piers at their base were 11 feet 4 inches by 32 feet 10 inches. Such a wide bridge was proved to be good foresight.

The Erie originally ran a broad gauge track (6 feet wide from center to center of each rail, as opposed to 4 feet 8 ½ inches), unique among railroads. As remembered by Robert E. Woodruff, a later President of the Erie Railroad, this allowed for wider cars, more comfortable travel, and larger loads. It also ensured other railroads could not connect to it, potentially taking away business.

Upon the completion of the line to Binghamton, celebrations were in order, as was customary of Erie after each of its many achievements. By now a man named Benjamin Loder had succeeded Eleazor Lord as President of New York and Erie. Loder ordered two excursion trains to be run through as a way of christening the newly completed section of line. At each little town, from Port Jervis, then onto Callicoon and Deposit, townspeople gathered to welcome the trains. Finally at Binghamton, bands played, feasts enjoyed, and speeches given by many of the distinguished guest that came from New York City. Among them, was President Loder. On the way back, passengers disembarked to view both the Cascade Bridge and the Starrucca Viaduct.

As Hungerford recalls in Men of Erie, cattle, pork, grain, butter, and all manner of produce were being brought to market in New York City by freight. Before the Erie, these products could only be transported from nearby counties, and had to be hauled by wagon and then by the Canal. Now all of Northern Pennsylvania and the Southern counties of New York could contribute. Milk quality in New York saw drastic improvements, and the benefits in price passed on to the farmer and consumer alike.

Later, the New York and Erie became synonymous with fresh meat from the Midwest, something previously thought impossible by those on the eastern seaboard. By the end of April, 1851, the Erie was completed. On May 14 of the same year, its inaugural train ran the entire length carrying, among others, President of the United States Millard Fillmore, and Secretary of State Daniel Webster. Celebrations took place at every town of significance along the way.

Edward Harold Mott recalls the inaugural trip in his book, Between the Ocean and the Lakes: The Story of Erie:

When Starrucca Viaduct came into view as the train glided down the western slope of the mountain between Deposit and Susquehanna, there was great enthusiasm among the passengers, and the trains were stopped for a few minutes at the viaduct. The President’s party and many others left their car to inspect and admire this greatest and most beautiful work of masonry then in this country, and enjoy the landscape scene of which it was the center, then, as now, one of the fairest on the continent.

Moreover, the New York and Erie brought a degree of prosperity to northeastern Pennsylvania, as Mott continues:

“Susquehanna [a depot just several miles past the viaduct] had then the most extensive railroad yard on the line.”

Change came to the towns along the Erie Railroad over time, and the viaduct has been there to witness them all. Susquehanna rose to be an important railroad junction and has since then declined in significance. As Young continues in his story, narrower, standard gauge track was installed, as standardization became necessary. This and other improvements came at great cost to the company. But the width of the Starrucca proved useful yet again, as two tracks were able to be installed side by side.

The advantages of the bridge continued to become apparent. Where wooden bridges were destroyed in fires, and steel trusses rusted beyond repair or loads became too heavy for them, the Starrucca Viaduct required little expense. In fact, a bridge just several miles farther up the track, the Cascade Bridge, was a wooden arch bridge and a wonder in its time, but was replaced by a fill because of fire concerns, despite the original cost of $72,000. The Starrucca Viaduct, designed in an era where train engines only amounted to ten or fifteen tons, each car being even less, now bears engines in excess of 400 tons, and cars of 125 tons. The enduring strength of the bridge is testament to much. From Thomas Telford and his work with stone arches, to Julius Adams, its designer, and James Kirkwood, responsible for its construction, the bridge exemplifies sound engineering practice and the wisdom of building to endure.

As David Plowden so succinctly states in his book, Bridges, The Spans of North America:

Their [stone bridges] disadvantage is the time it takes to build them, piece by piece, each stone needing to be quarried, dressed, and individually fitted. In an abstract sense, to “take time” has never been a basic part of the pioneer approach to doing things. American building, with few exceptions, has generally emphasized the art of accomplishing rather than the accomplishment itself…

Though stone-masonry construction was the exception, its long-term advantages were clearly understood by the American engineers who used it… Today it [the Starrucca Viaduct] ranks as one of the finest pieces of masonry construction anywhere.

And yet the bridge is not without need. Young notes many of these needs in his book, which include the following events: Over its lifetime, it has seen its stone sandblasted and mortar repaired. Crawl spaces have been added to assess the spandrel walls, which were repaired in places by cement and rebar. The deck has been waterproofed twice, and side walls have been reinforced. But despite all these repairs, the bridge appears almost entirely the same in its appearance as it has since its construction.

In 1973, it was nominated for an appearance on the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission’s Register of Historic Places, the federal government’s National Register of Historic Places, and the American Society of Civil Engineers’ list of National Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks. On October 14, 1973, the National President of the ASCE, John E. Rinne presented a plaque to the Erie Lackawanna Railway Company’s chief engineer, Robert F. Bush and general manager, Robert L. Downing. A ceremony was conducted, and two Erie Lackawanna trains passed each other on the viaduct.

Throughout history, the Starrucca Viaduct has made its way into Appleton’s Journal of Literature and Art, New York’s The Independent, various area newspapers, and many books of bridge and railroad history. Jasper Francis Cropsey, a famous American landscape artist, painted the Starrucca Viaduct, Pennsylvania currently housed in the Toledo Museum of Art.

Today the Starrucca Viaduct has come to stand for much. Built in the narrow time period when stone arch bridges were economical options in America, it exemplifies the art of bridge building and civil engineering practice. It is also a small, but nonetheless important, part of our nation’s transportation infrastructure. In its own capacity, the Viaduct has helped people and goods to travel great distances and serve many purposes for over 150 years. For those who have made the bridge a part of their lives by building, maintaining, using, visiting, or even living near it, it has doubtlessly formed memories they will not soon forget. For these things the Starrucca Viaduct stands testament.

Sources:

- Benson, Hosea M. “How The Stone Bridge Was Built At Lanesboro.” Montrose Independent. 24 Dec. 1901.

- Berry, Paul. “Erie Railway: Starrucca Viaduct – 1848.” Historic American Engineering Record, National Park Service. 1984.

- Hungerford, Edward. Men of Erie, a Story of Human Effort. New York: Random House, 1946.

- Mott, Edward Harold. Between the Ocean and The Lakes: The Story of Erie. New York: Ticker Publishing Co. 1908.

- New York Daily Times (1851-1857). New York, N.Y.: May 6, 1853. p. 4 (1 page)

- Nolan, Robert E. Jr. “Lehigh Valley Section, American Society of Civil Engineers.” Letter. 28 Sept. 1973.

- Plowden, David. Bridges: The Spans of North America. London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2002.

- Woodruff, Robert E. Erie Railroad –its beginnings! Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1945.

- Young, William S. Starrucca: The Bridge of Stone. Privately Published. 2007.