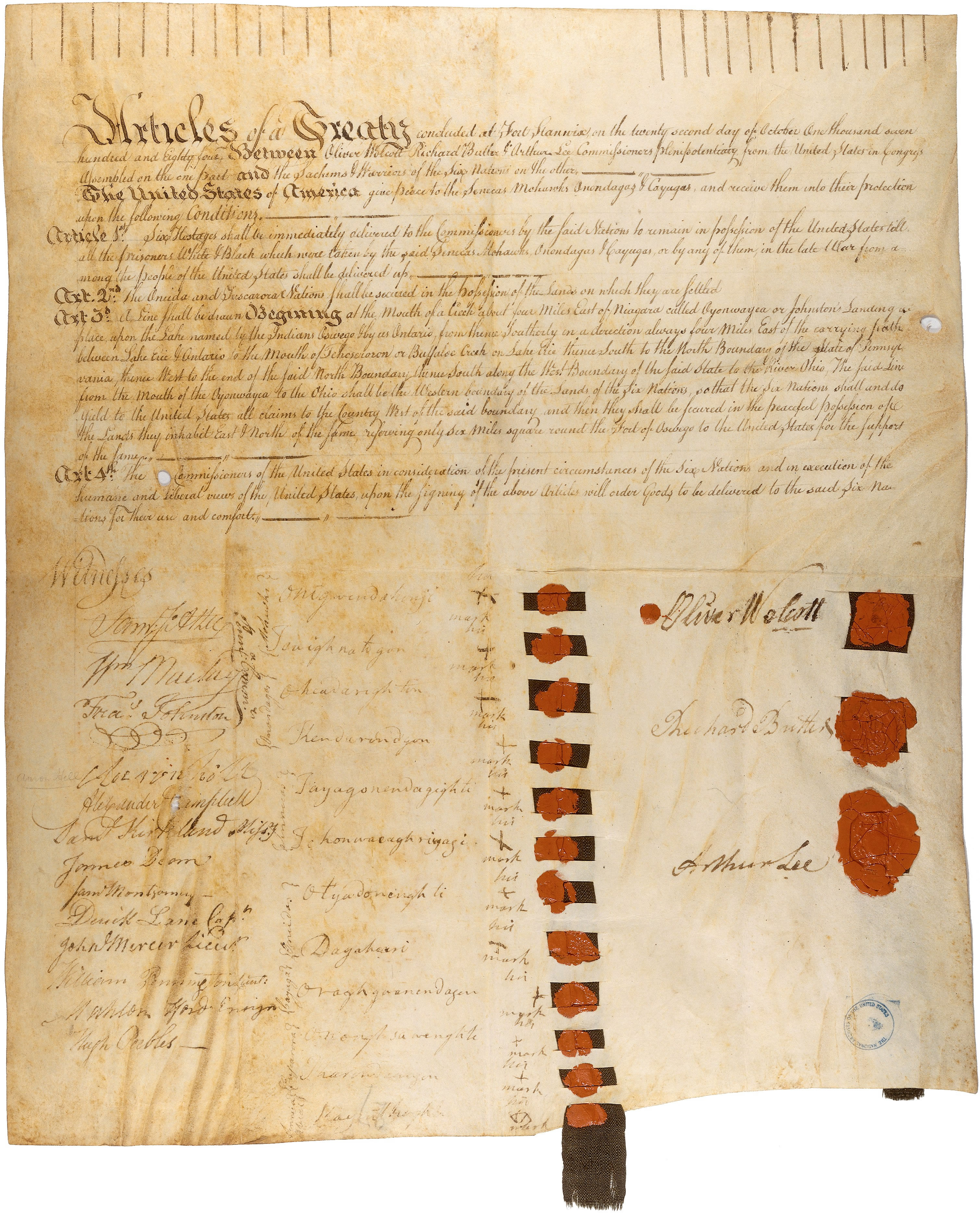

The early relationship between the United States and the Native Americans of The Six Nations was, at best, tumultuous. Tensions flared as both parties struggled to maintain control over their claimed territory, and the resulting atrocities from both parties fueled hostilities. In 1784, the earliest legitimate steps towards peace were taken with the signing of the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. It was the first agreement ever made between any Native American nation and the newly formed United States of America. This treaty successfully paved the way for Pennsylvania’s growth, and set a precedent for all future clashes between the United States and the Native Americans.

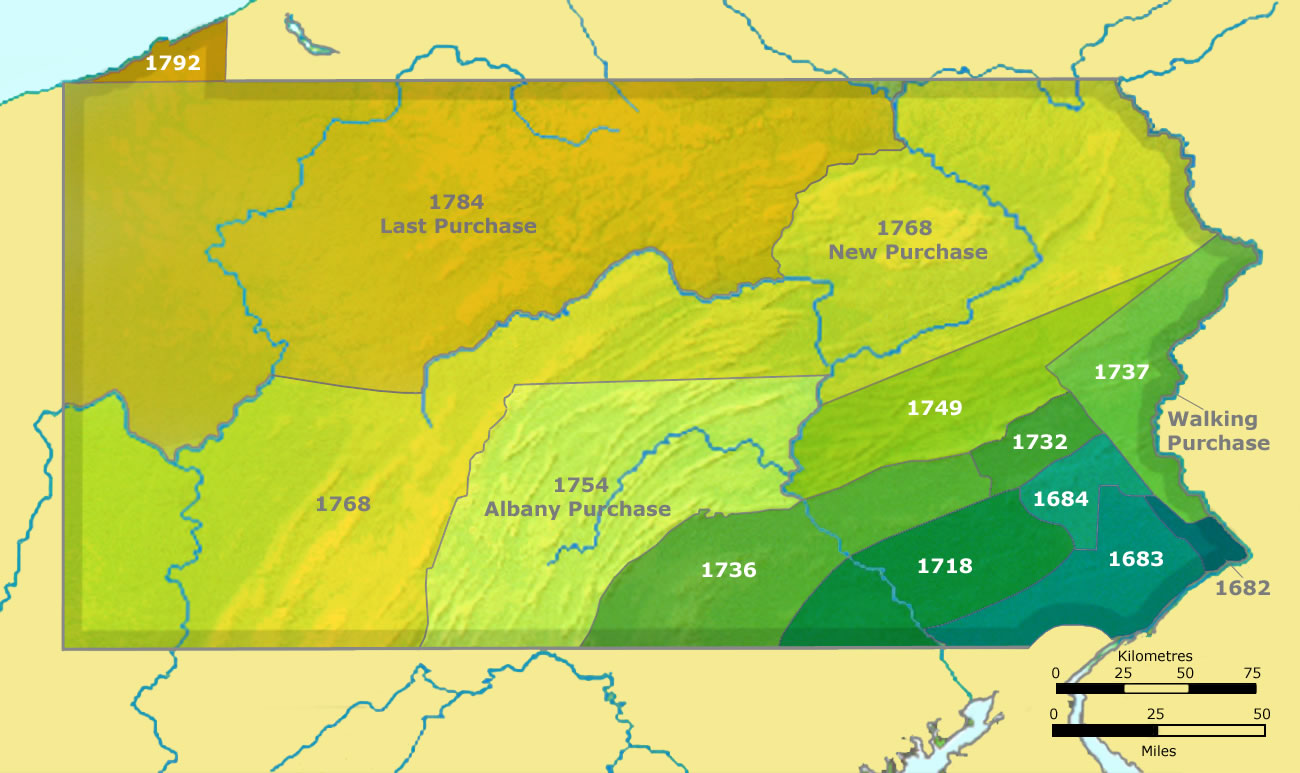

Before American independence in 1783, the British handled all conflicts with the Native Americans. There had been countless treaties between native tribes and the British dealing with such topics as trade and the western border of the colonies. In 1768, at the first treaty of Fort Stanwix, the frontier in Pennsylvania followed the western branch of the Susquehanna River and then continued westward along the banks of the Ohio River. Essentially, the Native Americans controlled the Northwestern quarter of modern Pennsylvania. For a time, agreements like this had effectively kept the peace in North America.

In fact, during the eighteenth century, amidst the numerous armed conflicts between England and France, the American colonies had been actively helping the Indian tribes that agreed to take up arms against the French colonies. In 1746, the governor of Pennsylvania, George Thomas, wrote a letter to the state assembly in which he expressed an interest in preparing The Six Nations Indians by providing “arms, ammunition, and other necessaries, for acting offensively against the French.” He continues by saying that it “seems next to impossible for them to maintain their neutrality much longer.” This observation would prove to be eerily accurate.

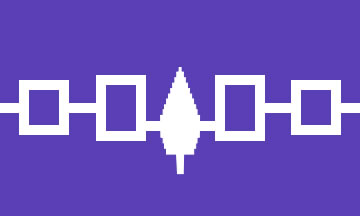

However, three decades later, the American colonies rebelled, and the Revolutionary War began. The British forged alliances with many Native American tribes from Georgia to Canada, including the tribes of The Six Nations. The Six Nations, otherwise known as the League of The Iroquois, was a confederacy of six Midwestern Indian Tribes: Mohawks, Oneidas, Onodagas, Cayugas, and Senecas, and Tuscaroras. Thus, the colonies officially entered a bloody war against the Native Americans. American colonists living in frontier settlements were under constant threat of attack, and the Indians showed no mercy. According to Henry Knox, the first Secretary at War in George Washington’s cabinet, “great numbers of inoffensive men, women, and children, fell as sacrifice to the barbarous warfare practiced by the Indians,” and he called these brutal killings “entirely unprovoked.”

One notable example of these attacks actually took place at Fort Stanwix. On August 14, 1777, the Massachusetts Spy published an excerpt of a letter dated July 28. It reports that on the previous day, soldiers in Fort Stanwix heard four gunshots and sent troops to investigate. The author continues by describing what these soldiers discovered five hundred yards from the fort:

The villains were fled, having shot, scalped, and tomahawked two girls and wounded a third. The girls had been out gathering raspberries. By the best discoveries we could make, they appeared to have been four Indians who perpetrated these murders.

Yet, in 1783, the British conceded at the signing of the Treaty of Paris, with no mention of their Native American allies. They withdrew their troops from the colonies, and essentially left the allies to fend for themselves. The Native Americans found themselves trapped directly next to their enemy without any assistance from the British. The war was over with England, but tensions were boiling over in North America, where there were continual attacks on civilians living in the frontier. It was clear that something needed to be done.

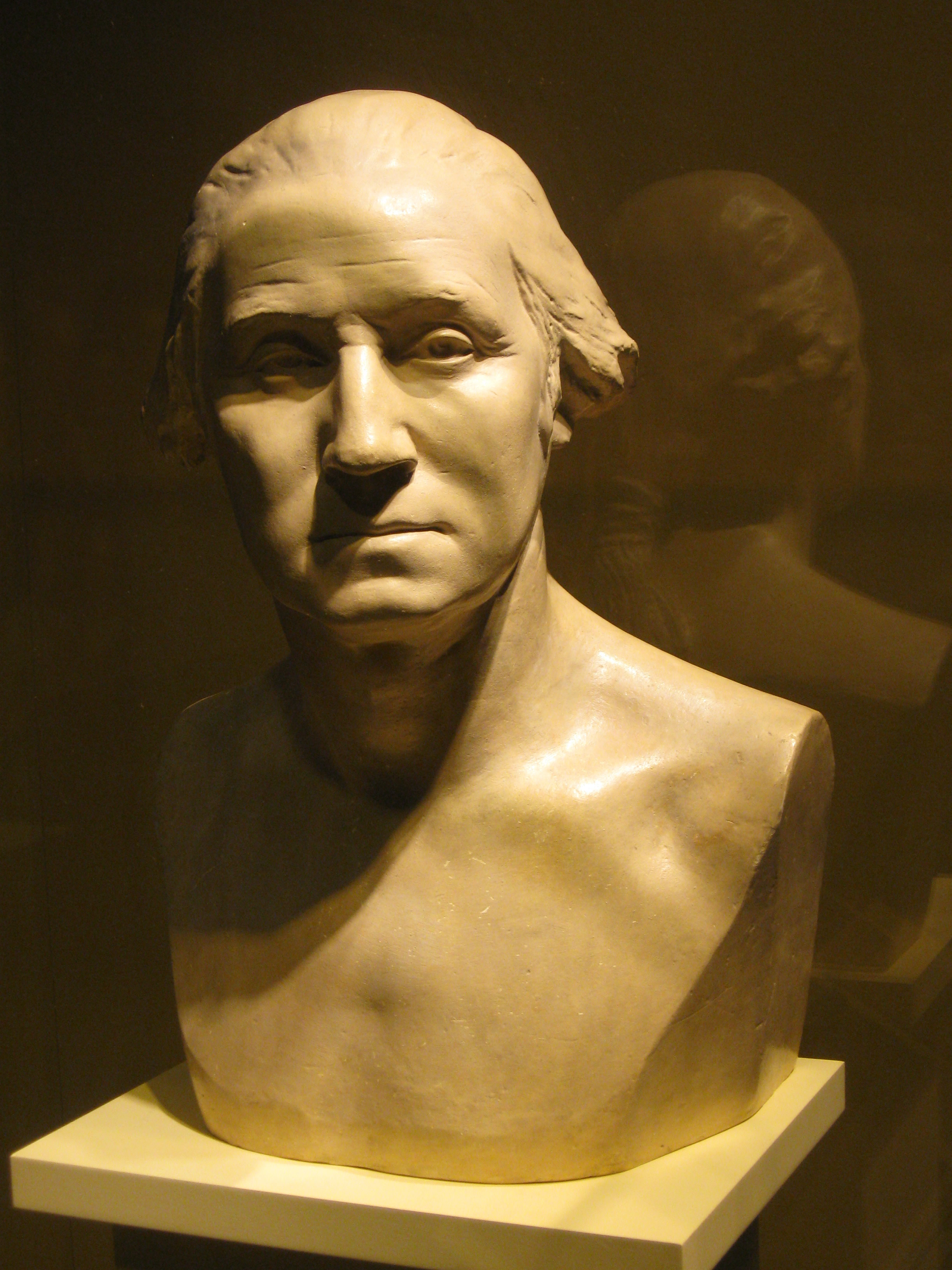

At that point, many Americans wanted to strike the Natives and end the war on their own terms, but General George Washington was the voice of reason. After visiting Fort Stanwix to understand the situation on the frontier, Washington stated that the Indians

were determined to join their arms to those of Great Britain and to share their fortunes, so consequently, with a less generous people than the Americans, they would be made to share the same fate, and be compelled to retire along with them.

He continued by broaching the subject of land cessions, stating, “That they would compromise for a part of it, I have very little doubt and that it would be the cheapest way of coming at it.” In the end, Washington convinced his countrymen to find a middle ground and peace was pursued.

Moreover, Washington knew that the Indians were in a precarious position after being abandoned by the English, and he was prepared to use their predicament as leverage. His ultimate goal was to form a boundary that both parties could respect and, in the process, push the Indians out of the contested territories, including much of what is now the state of Pennsylvania. Thus, the British treaties of 1775 and 1776 were obvious starting points for negotiations with The Six Nations Indians. In The American Apollo, however, Henry Knox summed up the general disdain of these agreements: “Those treaties were too feeble to resist the powerful impulses of a contrary nature, arising from a combination of circumstances at the time.” Significant changes had to be made.

Nonetheless, in the wake of the new U.S. independence, it wasn’t clear if states could independently make treaties with the natives that occupied their lands, or if that power was reserved for the federal government. Initially, Pennsylvanians attempted to deal with the issue on their own, but the United State Congress put an end to this in 1783. It was decided that the federal government would deal with the Native Americans and, to placate the state, they agreed to appoint a Pennsylvanian as one of the several commissioners in charge of holding the peace talks.

New York State Historical Society, see information below.

Pennsylvania effectively fell into line and agreed to work with Congress, but the New York legislature decided to ignore the federal government and deal with the Six Nations on its own. The authorities in New York invited the Indian leaders to Fort Stanwix, modern day Rome, NY, in 1784. They prepared to proceed while the federal commissioners were left behind in the colonies gathering troops for protection. However, when Congress received news of this ruse, the federal commissioners demanded that New York assemble 165 soldiers to act as escorts for the federal commissioners. In response, New York Governor Clinton, with the support of his own commissioners, used hollow administrative excuses to refuse the sending of any troops at all. Furthermore, he admitted that he was negotiating peace with the Six Nations and that New York would allow the federal authorities to attend the meeting, “excepting however and positively stipulating that no agreement be entered into with the Indians, residing within the jurisdiction of this state (and with whom only I mean to treat).”

On August 31, 1784, representatives from the Six Nations, New York, and Congress began to trickle into Fort Stanwix. Conferences were set to begin immediately, but no representatives from the Oneidas or Tuscaroras were present. According to tradition, each of the Six Nations needed to be present in order to form a binding agreement. It was quickly revealed that the Oneidas and Tuscaroras were reluctant to attend the gathering for fear of losing their lands. Consequently, a committee was dispatched to send a message of goodwill to these tribes, and on September 3, the necessary representatives arrived. The very next day, formal negotiations began and the uncomfortable issue of land cession was brought to the forefront. Against the recommendation of Congressman Duane, Governor Clinton opened the talks by denying the rumors that the United States planned to claim Indian lands, but declared that boundaries needed to be established. On the subject of the rumors, representatives of the Oneidas and Tuscaroras said, “We have utterly rejected and disbelieved these Reports,” but continued by reminding the commissioners that the boundaries had already been established in the 1768 Treaty at Fort Stanwix. Thus, members of both parties stubbornly entered a deadlock situation and progress came to a halt.

By stitching together the bits of information that is known about the fort itself and the activities of its inhabitants, one can paint a fairly bleak picture of life in Fort Stanwix during this time. According to Henry S. Manley in The Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1984), “The road seems to have been little improved. Washington had said that it was not passable for carriages… there were some bad places, which in the dark of night might be dangerous.” The road, it seems, provided the incoming commissioners with some insight as to the condition of Fort Stanwix. Twice in the preceding three years, in 1781 and again in 1783, the fort had been destroyed by fire and very little had been done to renovate it. Beyond the construction of some storage facilities and a council house, it seems that the fort was in complete disrepair. Rumors also swelled that the negotiations were hindered because the men were imbibing too much, and all of the “spirituous liquors” were seized and held until an agreement could be reached to finally put an end to the intoxication.

By October 20, the talks finally began to proceed, although stern words were not rare. One of the commissioners, for instance, told the Indians, “When we offer you peace on moderate terms, we do it in magnanimity and mercy. If you do not accept it now, you are not to expect a repetition of such offers.” The terms of the treaty were laid out and were broken into four articles: the release of hostages, the lands that would remain under Indian rule, the re-drawing of the United State’s borders, and an offering of goods to the Indians “for their use and comfort” in “consideration of the present circumstances of the Six Nations.” The members of the Six Nations were somewhat divided on the subject of land cessions, but a chief from the Seneca Nation, named Cornplanter, took a cooperative stance. He believed that seeking peace through diplomacy was in the best interest of his people, and was instrumental in bringing the negotiations to a close. After being presented with the terms of the treaty, Cornplanter commended the Americans by saying, “You have this day declared your minds to us fully, and without disguise. We thank you for it.” Ultimately, the Six Nations Indians were persuaded to accept the fact that some of their lands would be ceded as spoils of war and that their American hostages would, of course, need to be released for peace to be established.

Two days later, on October 22, 1987, the treaty was signed. The next day, in addition to the terms of this federal treaty, the state of Pennsylvania paid one thousand dollars to the Six Nations. For this, the Iroquois agreed to completely move out of Pennsylvania, with the exception of the Cornplanter Reserve, which was named after Chief Cornplanter in honor of his efforts to reach a peace agreement. This area measured eight hundred acres and followed the Allegheny River starting just below the New York state line; the land was set aside for the use of Chief Cornplanter and his descendants. The reserve remained in Native hands until the construction of the Kinzua Dam from 1960 to 1965.

With this act, the last of the Indian tribes withdrew from Pennsylvania, and the state’s citizens safely began to develop the western frontier. Furthermore, as a testament to the Indians’ treatment of their ninety-three American hostages, “some twenty or thirty captives either remained with the Indians or returned to them after being released,” according to George Henry Harris in The Life of Horatio Jones.

In the years immediately following the signing of the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the United States government maintained a supportive position towards its neighboring Native Americans. In a 1790 speech given in Philadelphia, George Washington empathetically offered the nation’s support to all Native American tribes. He told them,

Your great object seems to be the security of your remaining lands, and I have therefore upon this point meant to be sufficiently strong and clear… the sale of your lands in future will depend entirely upon yourselves… When you may find it for your interest to sell any parts of your lands, the United States must be present by their agent, and he will be your security, that you shall not be defrauded in the bargain you shall make.

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix represented a monumental step forward that demonstrated that peace was a possibility between the Natives and Americans. Unlike many of the preceding agreements, the Native Americans weren’t subjected to overt manipulation, and the mutual respect shown at Fort Stanwix became a model for future treaties. It was also an early victory for the United States Congress in its power struggle with the states. Most importantly, it paved the way for Pennsylvania’s growth and development. After 1784, cities such as Pittsburgh were free to prosper and forever change the state.

Photo of Chief Cornplanter used courtesy of the New York Historical Society with the following information: Ki-ou-Twog-Ky (also known as Cornplanter), 1732/40-1836, 1796, by F. Bartoli, oil on canvas,30 x 25 inches, Collection of the New-York Historical Society, accession number 1867.314.

Sources:

- “3. Little Turtle’s War (1786–1795).” Political History of America’s Wars Online Edition. CQ Press Electronic Library. <http://library.cqpress.com.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/phaw/polhis-ch03>.

- Burd, J. V. and R. Haswell. “The following are copies of two treaties…” Charleston Evening Gazette 27 Aug. 1785: 2.

- Deardorff, Merle H., adapted by Harold L. Meyers. “Chief Cornplanter.” Historic Pennsylvania Leaflet No. 32. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1994.

- Knox, Henry. “The causes of the existing hostilities…” American Apollo 5 Oct. 1792: 60.

- Manley, Henry S. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix 1784. Rome, NY: Rome Sentinel Company, 1932.

- “Review of the History of the rise…” The Albany Gazette, 23 Feb. 1821: 2.

- Robinson, Silvanus W., Henry Baker. “Removal of The Indians.” American Advocate 3 July 1830: 1.

- Street, Joseph M. “The Kentucky-Spanish Association, Blount’s Conspiracy, and General Miranda’s Expedition.” The Western World 18 Oct. 1806: 2.

- Thomas, George. “A Message From The Governor To The Assembly.” Pennsylvania Gazette 28 Jan. 1746.

- “Treaty with the Six Nations (Treaty of Fort Stanwix), 1784.” Political History of America’s Wars Online Edition. CQ Press Electronic Library.<http://library.cqpress.com.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/phaw/polhis-980-40...

- “Worchester August 14th…” Massachusetts Spy 14 Aug. 1777: 3