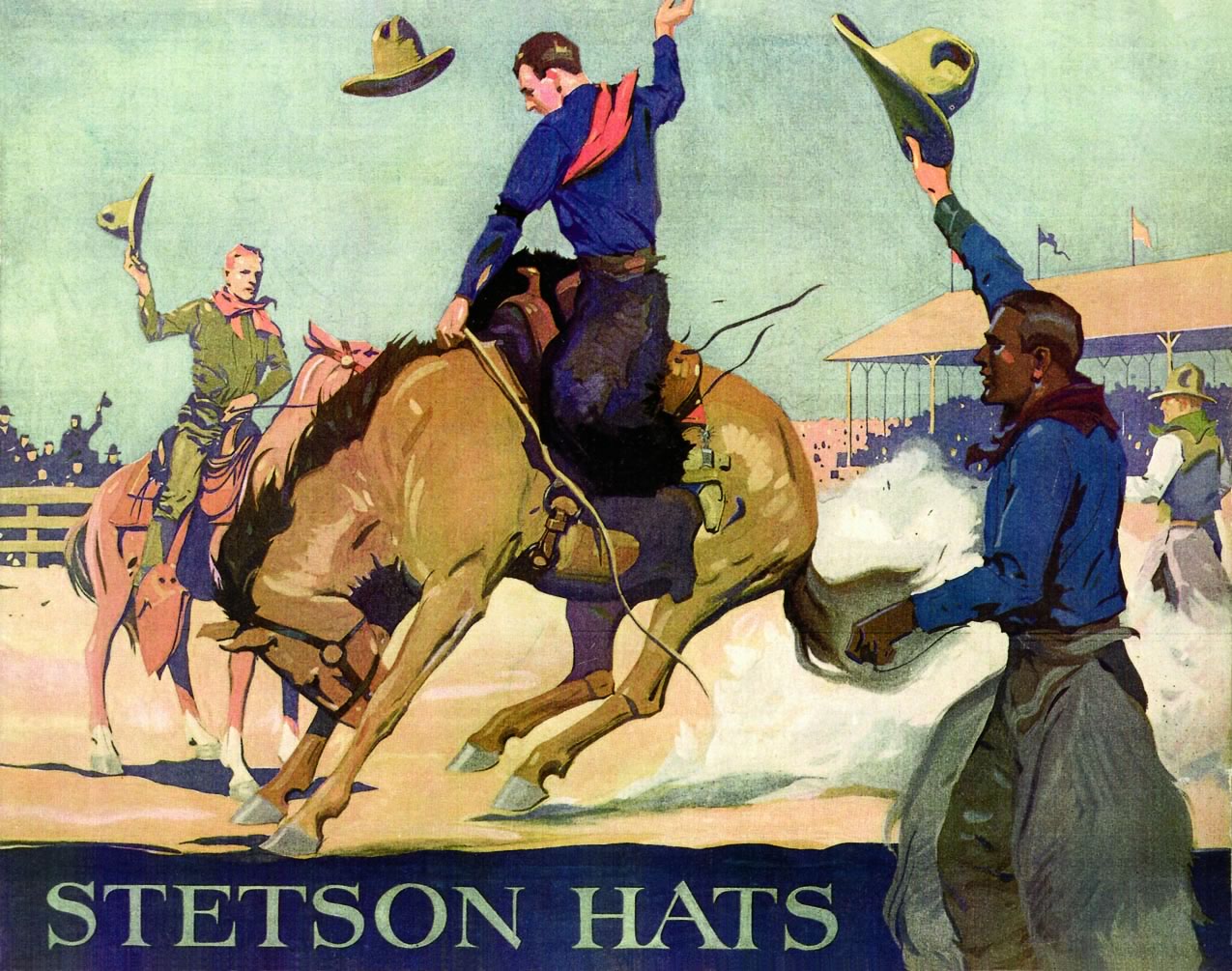

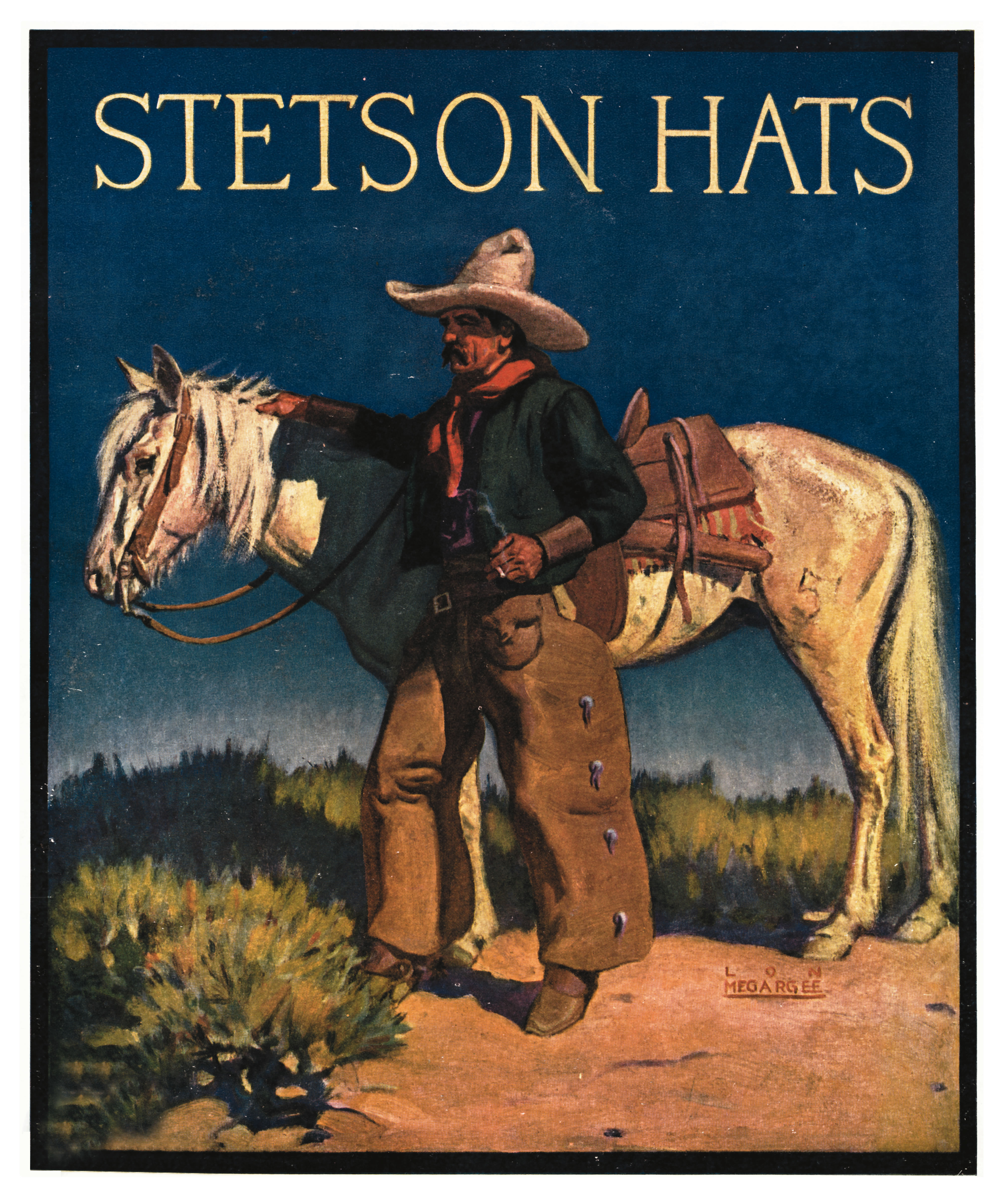

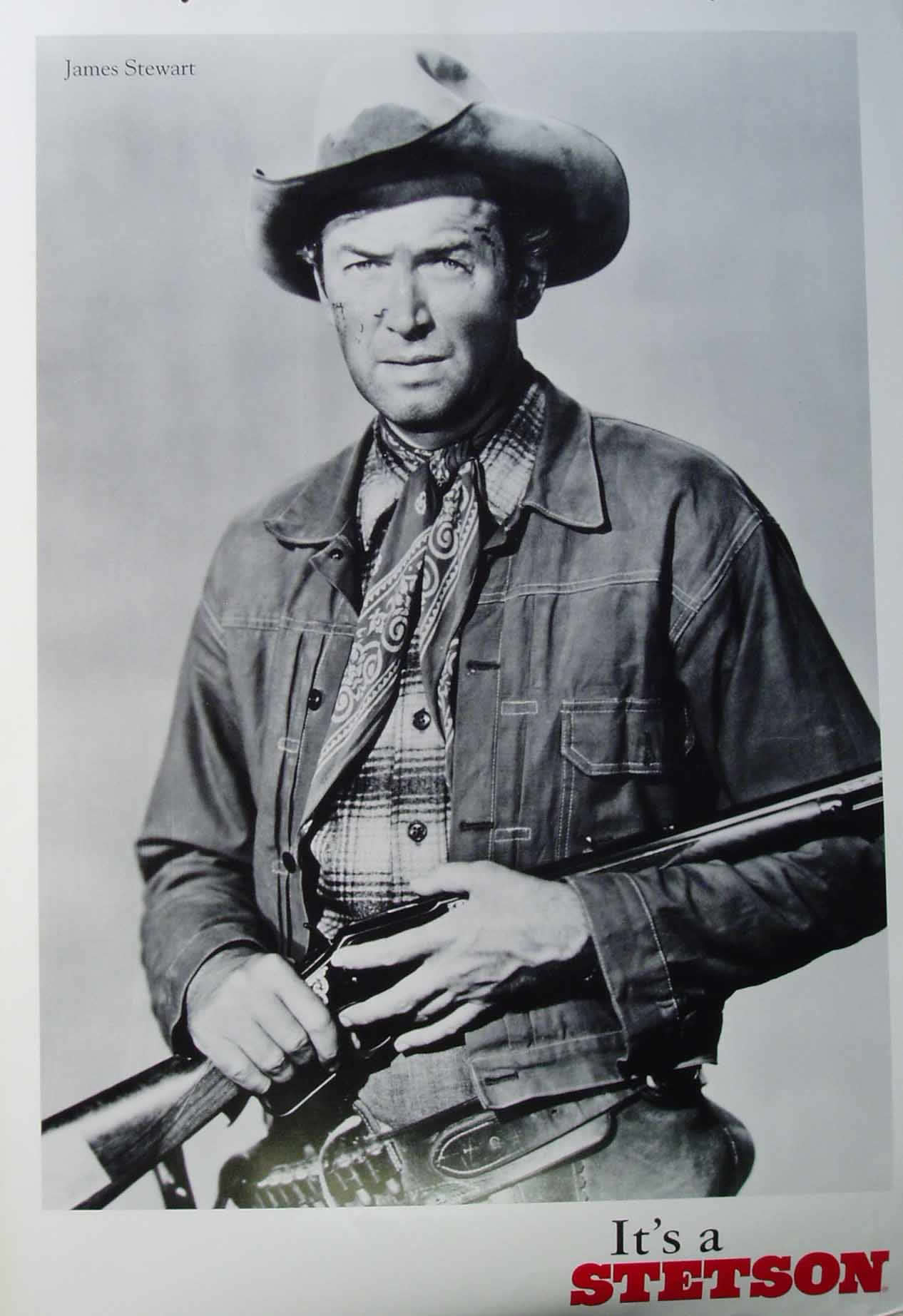

When we think of the American West, we think of vast plains, towering mountains, herds of cattle, and cowboys: the West's most famous protagonists. The image of the cowboy is defined by lassos, boots, jeans, and the iconic cowboy hat. The idea of the cowboy hat conjures up images from John Wayne and Clint Eastwood movies. When a cowboy hat comes to mind we don't normally think of Pennsylvania, but maybe we should. After all, the cowboy hat as we know it today, with its wide brim and high crown was first developed by a man named John Batterson Stetson, a famous Pennsylvania resident. He began his first hat business in Philadelphia in 1865, where he eventually manufactured the hat that made him famous—the Boss of the Plains. In creating the first cowboy hat, John B. Stetson has made his mark on Western iconography.

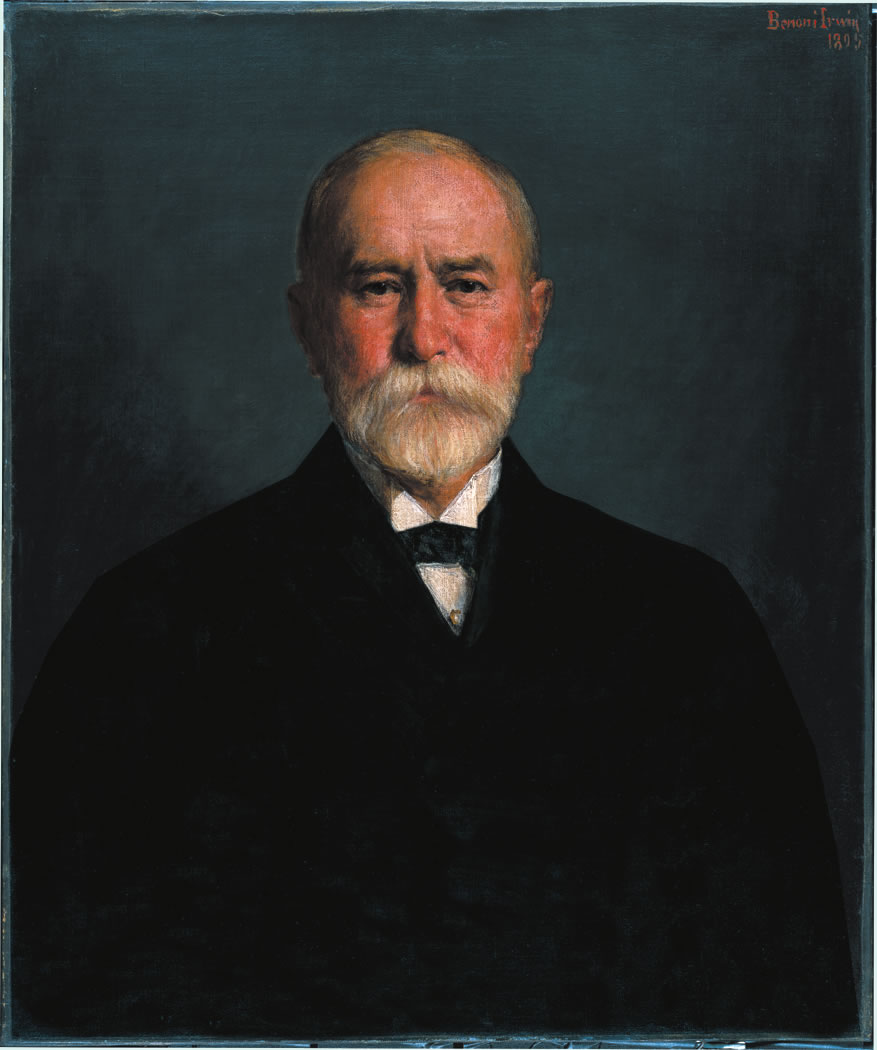

John B. Stetson was born in 1830 in Orange, New Jersey. His beginnings were humble as the son of a hatter and the seventh of twelve children. A hat maker or hatter was not a well respected profession at the time. Hatters were seen as unreliable, lazy drunks, but John's determination and good business practices would help change that stereotype. In his youth he was taught the skills of the trade and worked for his father and brother making hats, selling them, buying raw materials, and training other workers. Eventually Stetson made plans to go into business for himself, but before he could start, his health took a turn for the worse. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis and was told that he only had a short time to live. John Stetson decided to quit the hat business and explore the western frontier before he died. While on his journey he made his way to St. Joseph, Missouri where he got a job in a brickyard. Showing his great propensity for leadership, he shortly became the manager and then a part owner. However, his bad luck continued, and a flood destroyed his facility.

After losing his job and his investment, he joined some pioneers on an expedition to Pikes Peak. During the trip, Stetson and his companions obtained many animal skins but had no method of tanning them. The plains they traveled through were bereft of trees and provided no protection from storms or the mid day sun. They would use the hides to make simple tents to protect themselves from the elements, but the raw hide tents would have to be quickly discarded. Stetson found a solution in techniques he had used to make hats for years. He showed the pioneers the process of making felt from animal fur that would be durable and water proof. He helped his fellow travelers make felt tents that would last and protect them from the rain. This method of making felt would be a staple of his hats for years to come. Stetson made his first wide-brimmed felt hat to amuse his friends. It met some ridicule but, because of its aesthetic appeal and its ability to protect the wearer from the elements, it became the envy of many of his acquaintances, including his first patron—a bull whacker who paid him a substantial five dollar gold piece for it. This was the first Stetson hat ever sold.

After about a year, Stetson's health had returned, so he took his earnings and headed back east to the city of Philadelphia to start his own hat business. Stetson had 100 dollars left to start his business by the time he reached Philadelphia. He used that money to buy tools and fur, as well as to rent a room on Seventh and Callowhill. Stetson began by making hats in the styles that were popular at the time. He would sell his hats to vendors and store owners a few at a time, but he soon realized that if he wanted to stand out from all the other hat makers he would have to do something different.

Stetson experimented with different styles by making slight alterations to already established ones. He would add an extra curl to the brim or change the crown a bit to create what he hoped would be the next hit fashion. He would wear his creations and display them to dealers to persuade them to order some for their stores, but they were uninterested in the styles he created and believed that fashion came from Europe and not from the mind of a lone hatter. Fortunately, this took a favorable turn when he created a light felt hat made out of a very fine fur. While showing a store owner his product, a customer became interested and bought the hat on the spot. The owner took an interest and ordered a dozen hats from Stetson.

It was his first success, so he immediately took all the money he had and bought the finest fur he could get. The hats Stetson made were suddenly selling, but his profit margins were quite low because of the cost of the fur and the fact that his hats retailed for only two dollars. Stetson would receive an order of fur every week and pay for it up front. On one of the days that the order was due to arrive he realized that he did not have enough money to pay for the fur, but to his amazement, the delivery man allowed Stetson to pay for the fur in a week or so without his even asking. Stetson was a religious man and saw this unsolicited payment extension as a sign that God would help and protect him.

After being inspired by this event he decided to make a bold move. Instead of trying to make the next hit in hat fashion, he figured he would make hats for the working man of the West. Stetson would make the style that he invented during his journey to Pikes Peak. With its wide flat brim and high, straight- sided crown, it was great for protecting the wearer from the rain and harsh sun. Likewise, the hat was ideal for working outdoors. He believed this style of hat would be well received by ranchers, bull whackers, miners, and other western frontiersmen. He called his creation “The Boss of the Plains.” To promote his product, he took a gamble and sent a sample hat to clothing vendors in every city in the Southwest with a letter asking them to order a dozen more. Shortly Stetson started receiving orders from all over the region.

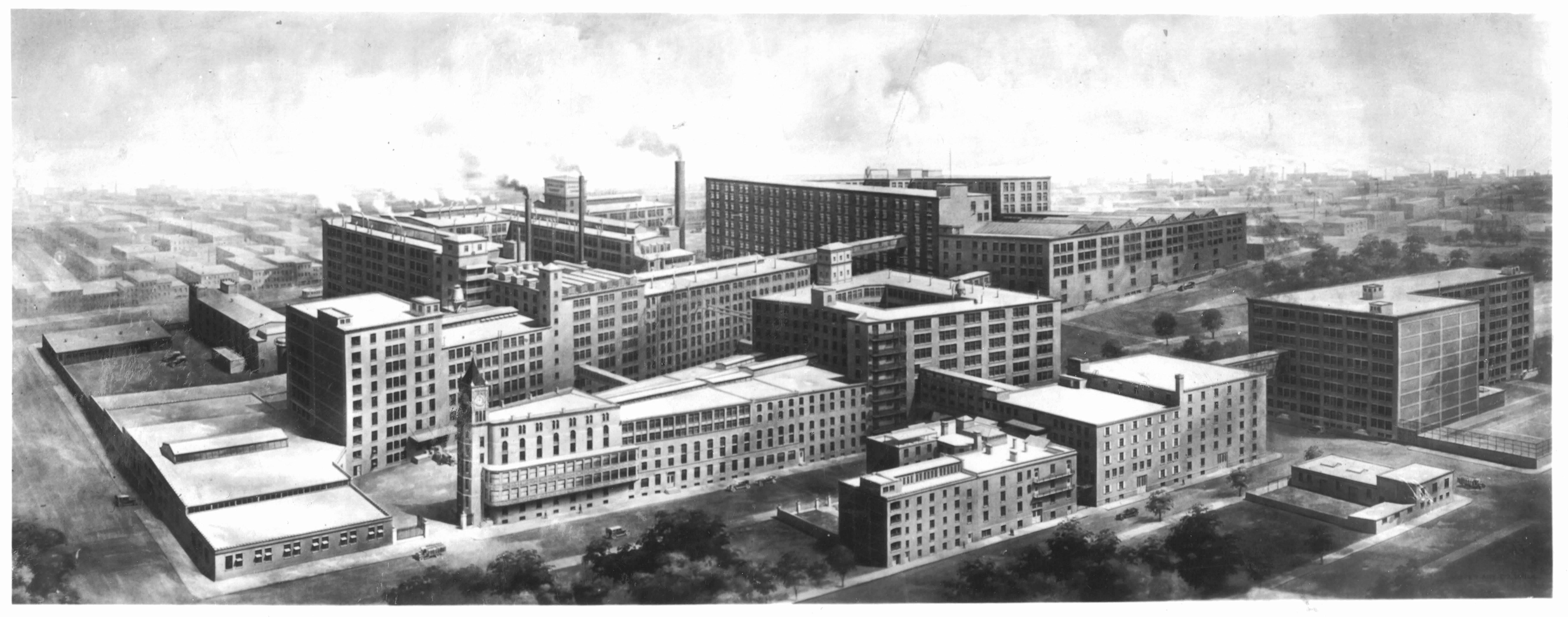

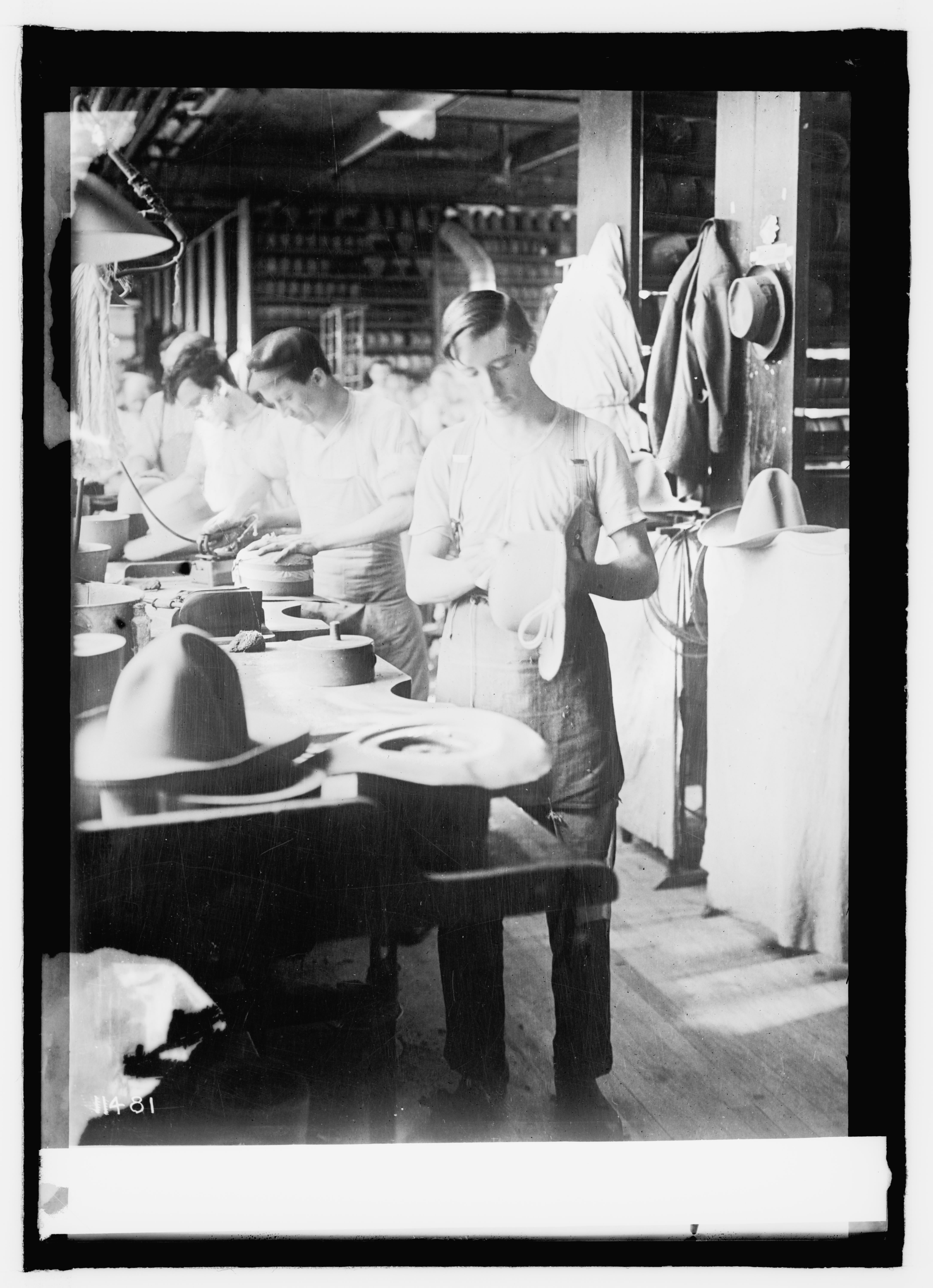

Stetson made three versions of the Boss of the Plains hat. The first one, made out of regular felt, sold for five dollars retail; the second one, made out of a very fine felt sold for 10 dollars; and the third one, made out of extra fine beaver or nutria felt, sold for 30 dollars. He never sacrificed quality to engage in price competition. Stetson believed in creating a quality product that would exceed the expectations of its customers. He let his product speak for itself, which is evident in the way he promoted his hat. Instead of sending vendors from the Southwest descriptions of the hats or advertisements for them, he let the hats do the talking. By sending the vendors the hats, he allowed them to try out the hats and see for themselves that they were durable and very functional while still being aesthetically pleasing. Stetson once said, “There is no advertisement equal to a well pleased customer.” Almost a year after he started making the Boss of the Plains hats, he moved his operation to a new location at Fourth and Montgomery Streets, then in the suburbs. Since he was no longer solely concerned with the local trade, he decided that it would be more economical to locate his factory where land was cheaper. The final great facility of the Stetson company would be at 1801 Germantown Avenue.

Stetson was a craftsman and businessman, but also a man of integrity and kindness. He believed in investing in his employees and treating them well. He paid his employees a good wage, had an apprentice system that encouraged long term employment, and set up a Christmas bonus system where the employees would be paid a bonus if they worked continuously throughout the year. Stetson's methods of management led to a factory of hardworking and skilled individuals. His efforts changed the perception of the hatter as a lazy, unreliable tramp to a trustworthy, hardworking, artisan. Stetson believed in being thrifty and saving one's money for a proper investment. He passed this idea on to his employees by encouraging them to buy their own houses. He created the Stetson Building and Loan Association to help his employees achieve this goal. Instead of going to the doctor he would have his doctor come to his office to treat him. Then, he started using his doctor to treat his employees' aliments as well. He soon was hiring more doctors to treat all his employees and he eventually built a hospital that treated not only his employees, but also members of the general public. Stetson provided healthcare for his employees at a time when that was unheard of.

Stetson hats were not just worn by cowboys and ranchers; they were worn by men of every background and social standing. The Stetson hat was adopted by the U.S. military and it is still worn by cavalry troopers for ceremonial purposes. The iconic hat has also been used by British, Canadian, and South African military. It is no wonder that Stetson hats are popular among military forces considering their durability and protection from the weather.

For all the Stetson’s great successes—and creating what would become the icon of the American West is surely a success—at least one of their production lines is virtually unknown to the average American. Stetson made women’s hats; not just western hats, but high fashion millinery. Jeffrey B. Snyder recounts in his book Stetson Hats and the John B. Stetson Company that Stetson had made some women’s hats in the late 1800s. Photographs of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show clearly depict women wearing men’s Stetsons. In roughly 1930, the Stetson Company would enter the women’s fashion hat realm, producing women’s millinery at its huge Philadelphia complex.

Before this the company had made a few hats specifically for women. In 1899, the Stetson Monthly showed two models for women: felt hats with wide brims and large feathers inserted in the bands. The Monthly described them as “the proper thing to match the tailor-made gown, for morning wear and when participating in any of the numerous field sports which women now indulge in.”

Women’s dress hats started production at the beginning of the 1930s in Philadelphia. They would produce the wide-brimmed hats that were the fashion as well as smaller hats such as the beret, the fez, and the pillbox. By the end of their first decade, turbans and hoods would also become popular. Snyder notes that “two lines of hats were produced each year, featuring 200 styles.”

The Stetson Company would not only mark their hats with their own logo, but would also add the names of a particular shop for which the hat was made. Snyder shows exemplar hats bearing marks of “Made exclusively for John Wanamaker Philadelphia,” “Claire Hat Shop, Pottstown, PA,” and “Boust & Stahl Sunbury, PA.”

During the 1930s, Stetson made a truly concerted effort to sell its women’s line. Holly Lim, Chief Operating Officer for the John B. Stetson Company, notes that Stetson was the one of the biggest advertisers in Vogue magazine in the 30s and 40s. In 1941, the Stetson Company moved its women’s hat production to New York City where it would stay for a decade.

By the early 1950s, however, Stetson would cease production of its women’s line. Snyder writes of a general downturn in women’s millinery in the period owing to changes in hairstyles and other style trends that made Stetson’s side line of goods less desirable for the company. Moreover, the post-War decline in hat wearing for both genders had reduced profitability to such an extent that company-wide consolidation necessitated first the return of the millinery division to Philadelphia and then its eventual closure.

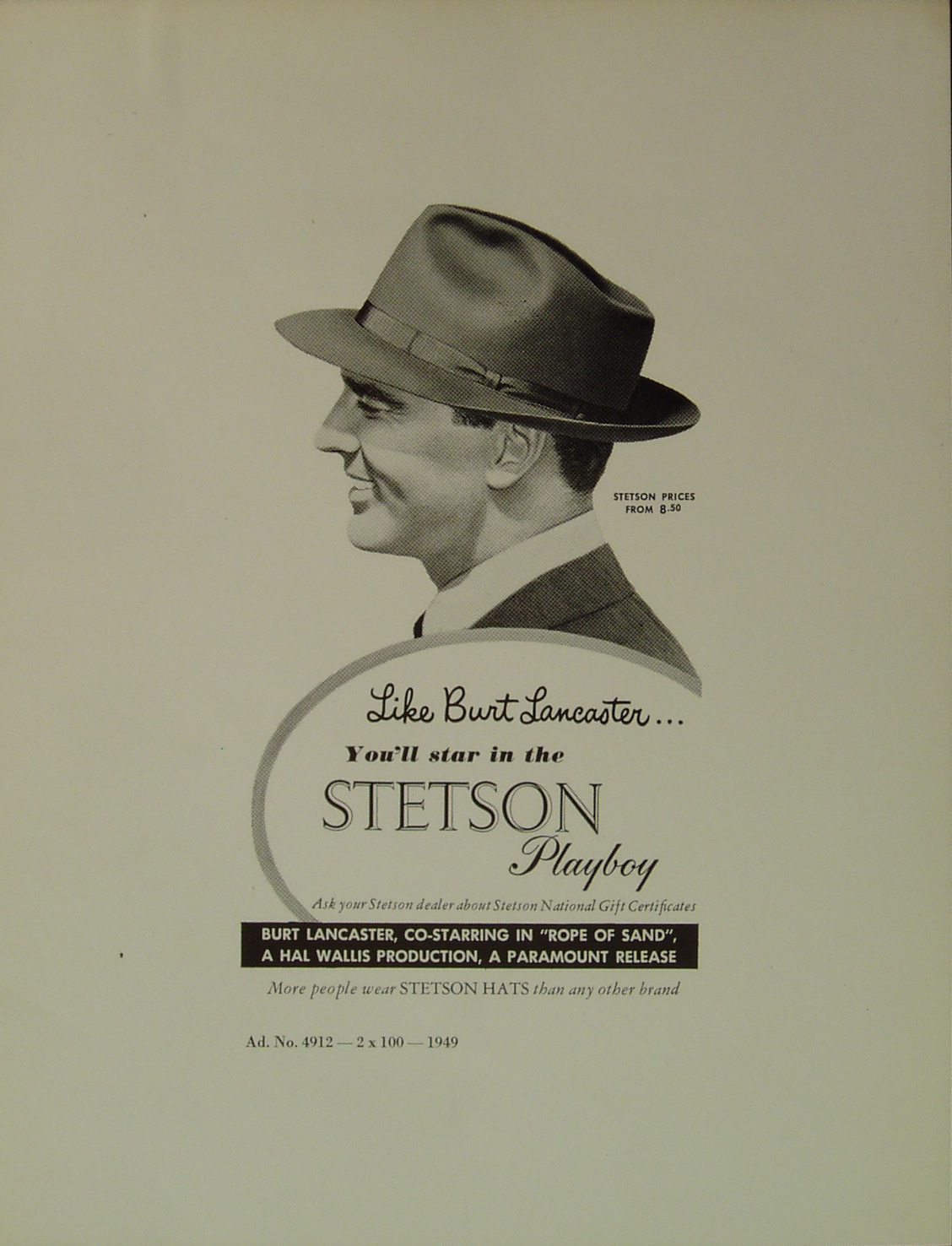

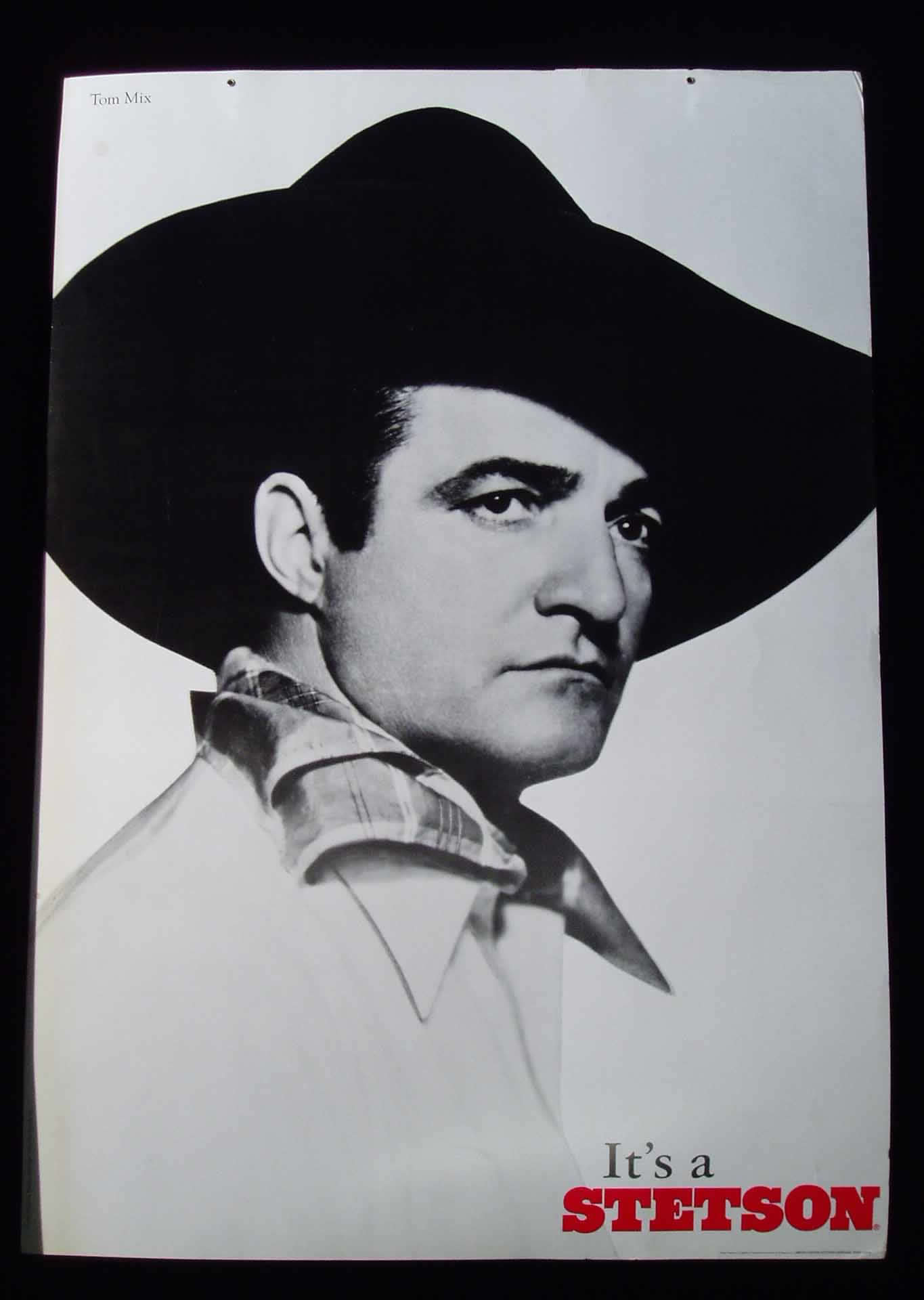

Recent years have shown that Stetson has forsaken neither quality nor the impulse to create fashion. In 2010, two major hat designers teamed up with the company to produce new lines of high end hats. Both Albertus Swanepoel and Billy Reid, winners of the Council of Fashion Designers of America Vogue Fashion Fund awards, have designed well-received lines suitable for men and women. While they differ from both the women’s “wedding cake crowns” of the 40s and from Tom Mix’s ten gallon hat, these new chapeaux carry on the company’s commitment to quality and its appeal to the American hat-wearing public.

John B. Stetson was an ambitious man who never sacrificed his product or his integrity to become a successful entrepreneur. It was his commitment to quality and practicality that led to the creation of the iconic cowboy hat. John B. Stetson chose Philadelphia to locate his factory, and even though the factory moved to St. Joseph, Missouri in the early 1970s and then to Garland, Texas in 1986 it is still a significant part of Pennsylvania history. Reporter Josephine Abader noted in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin in 1952 that the company The Stetson has been called “the finest hat made in America” by the Springfield Daily Republican newspaper, and the Stetson website proudly proclaims, “Stetson, it's not just a hat, it's the hat,” – a statement given credibility by the Stetson’s history as an icon. Wearing a Stetson has taken on a variety of connotations over the years, from asserting masculinity to making a statement about one’s principles.

In one of a series of essays on Stagger Lee (an African American taxi driver convicted of murdering a man over a Stetson hat in 1895), James Hauser argued that the Stetson was an important symbol of masculinity and freedom, particularly for African American men after emancipation. “Slaves were not permitted the status of manhood by their slave owners--an adult male slave was considered to be a boy, not a real man. Therefore, if the Stetson was a symbol of manhood, a Stetson on the head of a former slave or son of a former slave certainly must have also been a symbol of freedom.” This connects directly with the original cowboy myth, which Marshall Fishwick argued in Western Folklore “appeals directly to the trait traditionally valued above all others in the United States: freedom.” Hauser wrote that the Stetson was also a prized possession for jazz musician Louis Armstrong, who once lost his hat while running away from an angry woman who believed he had cheated on her, who then “took it and immediately sliced it up with the razor. Certainly, with her use of the razor, she was sending a message to Armstrong about what she was angry enough to do to him...or certain parts of him.”

The Stetson-wearing protagonist of Philadelphia writer Owen Wister’s classic novel The Virginian helped connect the hat with heroism on top of masculinity and independence. Before Wister’s novel, reports Ben Macintyre for The Times, “cowboys were usually depicted as murderers and hoodlums, and until the late 1880s “cowboy” was an insult, synonymous with “drunkard.” Wister’s cowboys, by contrast, asked questions first and shot later… they didn’t swagger or posture, and they sought self-improvement through literature. The Virginian reads Shakespeare and Sir Walter Scott.” The novel, published in 1902, helped set the foundation for the western movies to follow, in which wearing a white Stetson was enough to make you the good guy. Tom Engelhardt of TomDispatch.com remembers sitting in a movie theater in New York City in the fifties, watching the following scene unfold:

We were catching some old oater which, as I recall, began with a stagecoach careening dramatically down the main street of a cow town. A wounded man is slumped in the driver’s seat, the horses running wild. Suddenly — perhaps from the town's newspaper office — a cowboy dressed in white and in a white Stetson rushes out, leaps on the team of horses, stops the stagecoach, and says to the driver: “Sam, Sam, who dun it to ya?” (or the equivalent). At just that moment, the camera catches a man, dressed all in black in a black hat &mdash and undoubtedly mustachioed — skulking into the saloon.

My dad promptly turns to me and whispers: “He's the one. He did it.”

Believe me, I'm awed. All I can say in wonder and protest is: “Dad, how can you know? How can you know?”

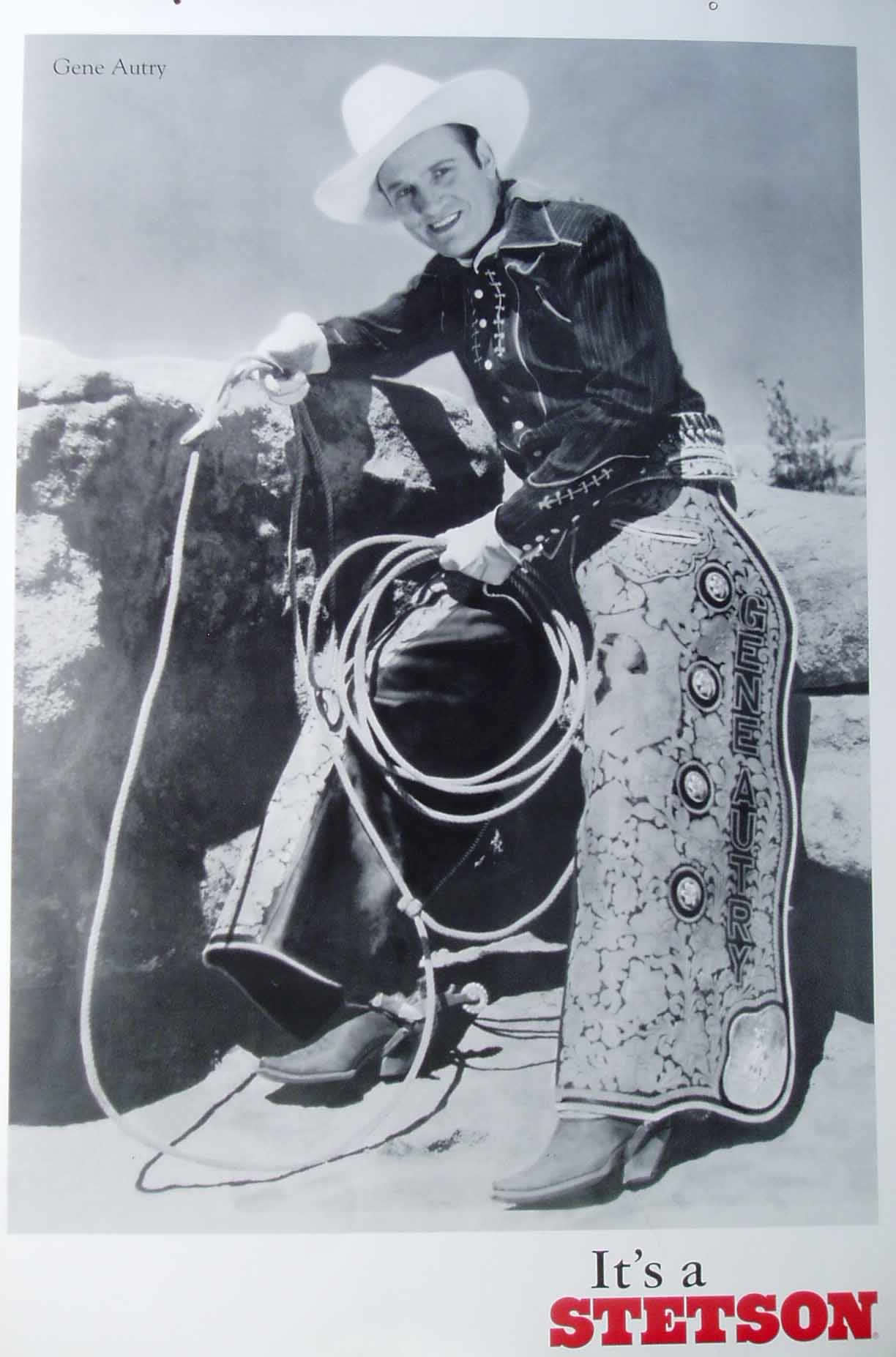

In westerns, the hero would traditionally wear a white Stetson and the villain would wear a black one. The plot of any western movie, wrote Tim Dirk for Filmsite, tends to follow a pattern - at the center of the action is the “classic, simple goal of maintaining law and order on the frontier in a fast-paced action story. It is normally rooted in archetypal conflict - good vs. bad, virtue vs. evil, white hat vs. black hat … schoolteachers vs. saloon dance-hall girls, villains vs. heroes, lawman or sheriff vs. gunslinger.” While these conflicts, like the hats used the represent them, dealt with solid shades of black and white, Elliott West argued in Montana: The Magazine of Western History that these simple conflicts confirm that westerns were a part of American mythology. “Like all myths, it appears simple. Certain elements and plots seem predictable, and detractors enjoy poking fun at its stark dualities and moral rigidities,” she wrote.

Simple or not, the image stuck. Wearing a white Stetson hat (as many U.S. presidents have done) was meant to indicate allegiance to a certain moral code, which is still associated with the hat. An anonymous contributor to eHow.com in a fashion advice column on how to wear a Stetson wrote, “The symbol of a true cowboy is not just his bravado, but what he wears on his head. A Stetson hat signifies not only a hero and a leader, but also a cowboy with class. All of these traits are enhanced by the way the hat is worn… Take off your Stetson hat as etiquette dictates. It is improper to wear a hat indoors and downright disrespectful to fail to take off the hat briefly to salute a lady.”

But an advertising campaign by Marlboro reminded the American public of Stetson-wearing cowboy’s former bad-boy status. Marlboro was having difficulty selling its filtered cigarettes, which were initially aimed at women. They decided the problem was that they were telling the American public that their cigarettes were for “sissies,” reported Kathleen Schalch for NPR. Marlboro then hired Leo Burnett, an advertising legend of the time, to turn their image around. "I said, 'What's the most masculine symbol you can think of?'” recalled Burnett in the radio broadcast. “And right off the top of his head one of these writers spoke up and said a cowboy. And I said, 'That's for sure.'" And so the Marlboro Man was born.

Marlboro used a variety of models for their ads, some of whom were real-life cowboys, but one thing was always the same: the white Stetson hat pulled low over the man’s face as he smoked his cigarette. Phillip Landry, the Marlboro brand owner at Phillip Morris in the 1960s, told NPR, "In a world that was becoming increasingly complex and frustrating for the ordinary man, the cowboy represented an antithesis — a man whose environment was simplistic and relatively pressure free. He was his own man in a world he owned." Many of Marlboro’s TV ads during the 1960s featured cowboys in Stetsons leading their cattle around to the theme song from the Magnificent Seven, inviting viewers to come join them in “Marlboro Country,” where they too could put their Stetsons on and be assured that they were still in control of the world they lived in.

Several U.S. presidents have tapped into the suggestive power of the Stetson hat. The introduction to a PBS movie on Lyndon B. Johnson explains, “The real Lyndon Johnson was a mover, a driver, a charmer, a bully -- six feet four inches tall with a size 7-3/8 Stetson hat. He loved food -- chili and tapioca pudding. He loved attractive women. He was a good dancer.” The image of a charming man with a fondness for the simple pleasures in life is crucially linked to the image of a Stetson hat, and Johnson used his hat to convince the public that he was just a common man with common interests. He would throw his hat from his helicopter to the crowds below when he landed – but if the person who caught it wasn’t one of his staff workers, there would be hell to pay. George Bush is also often associated with the Stetson, as is Ronald Reagan, though the latter two in particular drew criticism for adopting a cowboy’s persona in dealing with foreign affairs. In the popular comic strip Doonesbury, Bush was often drawn as an empty Stetson hat floating above an asterix, a reference to the phrase “all hat and no cattle.”

American folklore expert Peter Tamony, in Western Folklore, argued that the Stetson fits with a culture full of hat references, and has come to be the poster child of that culture. “In figures of speech, the hat is big in traditional colloquial English, and in American phrase and proverb. To bet one’s hat, figuratively, meant to stake all…And to give a politician something to hang his hat on is to make a proposal for consideration, to give him an issue,” he wrote. Tamony suggests that while the wide-brimmed sombrero is a national symbol of Mexico, the Stetson is its northern counterpart, because despite the occasional sensational headline about the death of the cowboy myth, images of rugged men in Stetsons continue to appear. The Stetson website similarly claims that the Stetson is “an icon of everyday American lifestyle. Because of its authentic American heritage, Stetson remains as a part of history and, for the same reason will continue into the future.”

Ultimately, the hat’s popularity today owes more to its connections to figures like Annie Oakley, Buffalo Bill, the Virginian, Pennsylvania’s own cowboy star Tom Mix, and the Marlboro Man than it does to the lives of real western settlers, though it could be argued that these fictional western heroes wouldn’t have been the same without the hat they all wore. Bill Bryson complains in an article called “How the West Wasn’t Won” for the Independent, “Scarcely a western movie has been made in which at least one character hasn't taken a bullet in the thigh or shoulder but shrugged it off with a manly wince and continued firing” – when, in fact, nineteenth century guns were slow enough that the bullet would continue to bounce around inside the victim, debilitating if not killing him, instead of exiting cleanly as the movies suggest.

This mythologizing of the West, Bryson writes, is similar to the way the Stetson hat has developed its own myth – many are unaware that it was invented in Pennsylvania by “a Philadelphian who never intended the hat to be exclusively associated with guys on horses.” But whether or not the stories in the movies have factual origins seems to be a matter of little importance for many. What matters is the idea of the Stetson-wearing cowboy, which has become much more than a story. This mythic figure has undergone countless shifts over the years, moving from drunkard to good guy to macho man to politician. But the Stetson hat, whatever it may mean at the time, is always in the picture.

The Center would like to thank Holly Lim of the Stetson Company for her assistance with this article.

Sources:

- Abader, Josephine. “Hat Firms Give City Reputation As a Millinery Center of the World.” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin 20 Oct. 1952: 23.

- Appel, Phyllis. The Missouri Connection: Profiles of the Famous and Infamous. St. Louis: Graystone Enterprises LLC, 2010.

- Bryson, Bill. “How the West Wasn’t Won.” Independent.co.uk. The Independent, 2 July 1994. 25 Aug. 2010 <http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/how-the-west-wasnt-won-wagon-tra....

- “Closer Look: Stetson Hats by Billy Reid.” Porhomme.com. 11 Oct. 2010. Por Homme. 21 Jun 2011 <http://www.porhomme.com/2010/10/closer-look-stetson-hats-by-billy-reid/>.

- Cole, Roland. “Important Change in Stetson Advertising Policy.” Printers' Ink 112. 23 Sept. 1920: 10-12.

- Dirks, Tim. “Western Films.” Filmsite.org. Filmsite, n.d. 25 Aug. 2010 <http://www.filmsite.org/westernfilms.html>.

- Engelhardt, Tom. “Tomgram: Kill Them! We are Going to Wipe Them Out!” TomDispatch.com. The Nation Institute, 1 June 2008. 25 Aug. 2010 <http://www.tomdispatch.com/post/174938/kill_them_we_are_going_to_wipe_th....

- Grubin, David. “Lyndon B. Johnson: Program Transcript.” PBS.org. Public Broadcasting Service, 1991. 25 Aug. 2010 <http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/presidents/36_l_johnson/filmmore/filmcredit....

- Fishwick, Marsall. “The Cowboy: America’s Contribution to the World’s Mythology.” Western Folklore 11.2 (April 1952): 72-79.

- Hauser, James. “The Symbolic Meaning of the Stetson Hat.” The Stagger Lee Files. 2009. 25 Aug. 2010. <http://sites.google.com/site/thestaggerleefiles/the-symbolic-meaning-of-....

- “The History of Stetson Hats.” Stetsonhat.com. 2010. Stetson Hats. 26 Aug. 2010 <http://www.stetsonhat.com/history.php>.

- “How to Wear a Stetson Hat.” eHow.com. eHow, n.d. 25 Aug. 2010 <http://www.ehow.com/how_2386606_wear-stetson-hat.html>.

- Hubbard, Elbert. A Little Journey to the Home of John B. Stetson. East Aurora, NY: The Roycrofters, 1911.

- “John B. Stetson Company.” Moody’s Magazine 17. Feb. 1914: 105-106.

- Kolpas, Norman. “The History of the Stetson Hat:How John Batterson Stetson Created the Classic Cowboy Hat.” Suite101.com. 31 Aug. 2009. Glam Entertainment. 9 June 2010 <http://norman-kolpas.suite101.com/the-history-of-the-stetson-hat-a144307>.

- Lim, Holly. Personal Communication with Alan Jalowitz. 5 Apr. 2001.

- Lurie, Maxine N. and March Mappen. “Stetson, John Batterson.” Encyclopedia of New Jersey. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2004. 778.

- Macintyre, Ben. “Shootin’ up the ol’ western myth.” Timesonline.co.uk. The Times, 20 Nov. 2004. 26 Aug. 2010 <http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/columnists/ben_macintyre/articl....

- Schalch, Kathleen. “The Marlboro Man.&rdquo