Swiftly cruising down Route 18 on a lazy Sunday afternoon, drivers will pass through many remote areas of Pennsylvania. As endless acres of farmland fly by, the ability to distinguish between communities is lost. Towns such as Burgettstown, Atlasburg, and Slovan simply blur together. Drivers might even pass through the borough of Frankfort Springs entirely unnoticed. Without batting an eye, the opportunity to view a truly historic site of Pennsylvania would be lost. But who could blame them? The borough of Frankfort Springs in Beaver County has a total population of only 130 residents. Regardless of size, the tiny borough is home to a well-hidden secret of 19th century American history: The Frankfort Mineral Springs Resort.

The tiny borough of Frankfort Springs actually grew out of the Mineral Springs Resort that once existed in the area. Local advertisements made Frankfort Springs seem extremely appealing and thus the resort was host to many wealthy individuals from the Pittsburgh area. Sherman Day’s Historical Collections of 1843 records an advertisement of the time: “Frankfort is a small village on the southern edge of the county, near which there is a mineral spring, much frequented by invalids. The spring is situated in a cool, romantic glen, thickly studded with forest trees.”

The owner of the lands on which the springs were located, Edward McGinnis, decided to build the resort to provide lodging for the many people who came to visit the springs. Opening its doors in the mid 1800’s, the Frankfort Mineral Springs Resort attracted much attention. But why would people travel thirty miles from Pittsburgh just to visit the area? Perhaps the Frankfort Springs town directory of 1837 summed it up best:

In Beaver County is a flourishing village, 26 miles from Pittsburgh, 20 miles from Beaver and thirteen miles from Georgetown. Near this place are located the Frankfort Springs, which are now resorted to by our western people, on account of their medicinal qualities, and delightful retreat from the cares and drudgeries of Pittsburgh.

And escape from the “cares and drudgeries of Pittsburgh” they did. Prosperous Pittsburgh residents would spend segments of their summers drinking from the mineral waters at Frankfort. The healing powers of the water from were considered medicinal, curing various ailments from indigestion to liver illness. The springs were also considered a place for the social gathering of the wealthy who commonly spend up to a month at the spa.

Because of the geology of the area, the water received natural filtration as it passed through layers of rock. McGinnis, saw the potential in this great business opportunity, and the business flourish.

The miraculous mineral springs were appreciated prior to the creation of the resort. The question of “who” actually discovered the healing properties of the water remains unknown. However, there is a recorded history of visitors patronizing the springs earlier than the mid 1800’s. It is believed that the Native Americans in the area were aware of the curative waters due to the Indian trail that ran in close proximity to the springs.

The first documented record of the springs is from 1772, when Levi Dungan claimed 1,000 acres of land, including the springs, outside of Pittsburgh. Unfortunately for Dungan, he did not truly understand the value of his land. In 1788, he sold 400 acres to Isaac Stephens for a total of 3 pounds 6 shillings 8 pence. In 1827, Stevens sold a small parcel of 12 acres to the future resort owner McGinnis. Stevens, unlike Dungan, perhaps saw the value in the land and sold the mere 12 acres for a profit of $300. The significant price difference indicated that the value of the land had skyrocketed.

The healing power of the waters was not simply folklore of the time. While the mythical powers of the springs were renowned and advertised, the curative powers were well documented by medical experts even prior to the resorts opening. One such expert, Dr. William Church of the Pittsburgh area, documented his study of the water in an article published in The Philadelphia Journal of the Medical and Physical Sciences in 1823. In the article, Church explained how he had traveled to the springs to conduct a set of ten experiments. Through his experiments, Church discovered that the water contained a wide variety of minerals, including carbonate of magnesia, which acts as a laxative. After finishing the experiments, experiencing the water, and interviewing many patrons of the springs who told stories of various cured ailments from arthritis to liver disease, Church concluded that the springs did indeed hold mysterious healing properties. According to Church, “Drinking the water, with the use of the cold shower bath, has been of great service to persons laboring under chronic rheumatism, gravel, dyspepsia, asthma caused by gastric irritation, general debility of the system, and to convalescents from bilious fever, and liver complaints.”

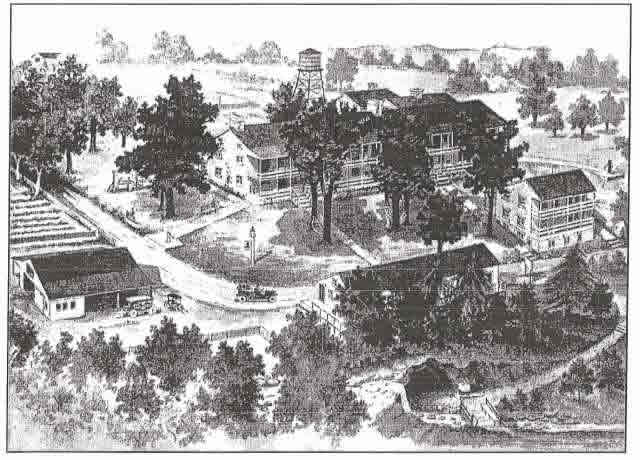

With a plethora of miraculous stories and the backing of medical science, the Frankfort Mineral Springs Resort enjoyed much success throughout the 19th century. In addition to drinking the water, guests were also invited to play tennis on one of the two courts and to visit the parlor or the dancehall. The food served at the resort was locally bought or raised by the resort’s farmers.

After it began to show its years of wear and several owners, the resort was purchased in 1884 by James Bigger. After paying $5,500 in the initial transaction, Bigger completed a full-scale renovation. The resort maintained its popularity into the early 1900’s, but then its popularity began to wane as the Victorian era faded. The resort became a place frequented by renters or travelers. In the 1920s, it was home to Route 18 Pennsylvania State Highway construction workers.

While it remained open despite declining popularity, the life of the Frankfort Mineral Springs Resort came to an abrupt, devastating end when it was destroyed by a fire around 1930. The exact cause of the fire remains unknown; however, the resort itself was unsalvageable and could not be rebuilt in the midst of the Great Depression.

The hollow shell of the resort remained until the land was acquired by Pennsylvania and Raccoon Creek State Park was created in 1967. The once flourishing spa had long since been forgotten. Today, the site of the former Frankfort Mineral Springs Resort lies on an easily unnoticed hiking path in Raccoon Creek State Park. Situated in Beaver County, the park consists of 7,572 acres including the 101 acre Raccoon Lake. In 1972, the park attempted to restore a piece of the resort history by restoring one of the guest cottages. Unfortunately, vandalism has since robbed this cottage of its displays. Due to the remote location, the preservation of the cottage was essentially unfeasible to monitor, and thus has remained bare.

Pennsylvania is certainly home to many well hidden pieces of American history. The Frankfort Mineral Springs Resort began operation over 150 years. The appeal of the miraculous healing powers of the springs drew many eager visitors, though the great legacy of the resort remains a quite gem of Pennsylvania history.

Sources:

- Bausman, Joseph H. History of Beaver County, Pennsylvania and its Centennial Celebration. New York: The Knickerbocker Press, 1904.

- Beaver County Recreation and Tourism. 10 Dec. 2009. <http://www.visitbeavercounty.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&....

- Church, William. “An account of the Frankfort Mineral Springs, &c.” The Philadelphia Journal of the Medical and Physical Sciences.Volume VI. Philadelphia, 1823.

- Day, Sherman. Historical Collections of the State of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: George W. Gorton, 1843.

- “Defunct mineral resort has a healing history.” Farm and Dairy. 16 Jan. 2003. 9 Apr. 2009. < http://www.farmanddairy.com/news/defunct-mineral-resort-has-a-healing-hi....

- Ryall, Kay. “Frankfort Springs One of First Settlements in Western Pennsylvania.” Pittsburgh Press 5 Nov. 1933: 12.