At the turn of the 20th century, Pennsylvania had proven to be an industrial wonder state. From the steel giants of Pittsburgh to the port city of Philadelphia, from the oil patch of the northwest to the forests of the northern tier, Pennsylvania offered the nation many important industrial resources. Yet, a city somewhere between these two major metropolises, Scranton—”the electric city”—created a buzz. Beneath the brightly lit buildings, it had been discovered that the Lackawanna Valley hid another kind of black gold, rich deposits of Anthracite coal unique to the region. The clean, hot-burning fuel was perfect for running machines and building empires in the steam-dominated era. In fact, there was so much coal in the region that it could sustain 80% of the world’s fuel demands, ranging from heating to transportation, without the aid of any other source.

Pennsylvania’s economy had the potential to benefit heavily from the coal; yet an efficient railroad system was required to transport this resource out of the valley and put it to use, one that could conquer the mountainous landscape. Up until this point, the system then in place was adequate, but in no way was it efficient. The system often required pushing engines, which were needed to assist the mile long trains up the 2000-foot elevation difference through the valley. After several years of operating in this manner, The Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad (DL&W) commissioned surveys and studies of alternate routes through the valley.

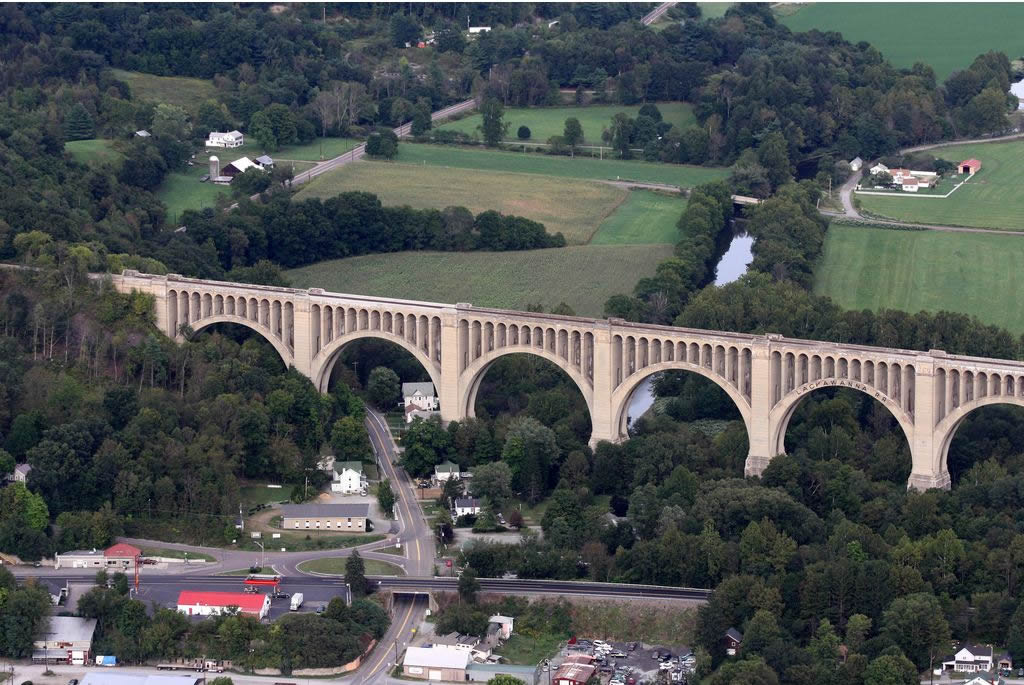

Designed by Abraham Burton Cohen, the Nicholson Bridge, originally known as the Tunkhannock Viaduct, was the world’s largest reinforced concrete bridge in the world. The Nicholson Bridge was so large that it required more than 167,000 cubic yards of concrete, enough to fill 52 Olympic sized swimming pools, and 1,140 tons of reinforcing steel in construction material.

The design called for 12 arches that spanned 2,375 feet, the outer two arches buried 100 feet into the hillside of the valley. The inner 10 arches span 180 feet and rise majestically 240 feet above bedrock. That’s almost tall enough to fit a 24-story skyscraper under the arches. The Wilkes-Barre Times even stated, “If the Flatiron Building in New York City were continued up Broadway from 23rd to 33rd street, filling the street from building line to building line it would represent a structure of about the same size and dimensions as the Tunkhannock Viaduct.” Atop the main spans, another series of 11 arches support the massive railway.

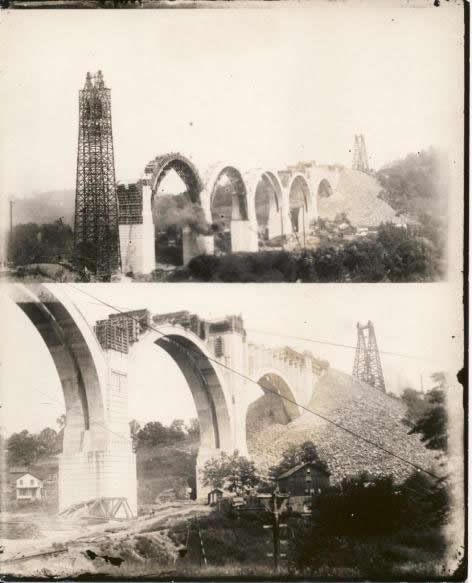

Other than its sheer size and earth moving machinery needed to build it, the methods described in the construction documents make this bridge a true marvel. Concrete had been used widely for centuries and it is renowned for its strength in compression situations. However, in tensile loading, concrete readily fails. Conveniently, a new technology had been recently developed that remedied the tensile, or tension, issues concrete structures inherently face. Steel reinforcing was implemented throughout the bridge, and steel bars were placed near the surface of the concrete, where tensile stresses are at a maximum, in order to prevent it from pulling apart. This particular construction method was a new and exciting idea that would come to influence future structures.

Another revolutionary feature of the bridge was that it was designed to be 34 feet wide, allowing for north and south bound trains to pass simultaneously. This replaced the need to switch track connections in order to cross. That feature, coupled with reducing travel by 3.6 miles and eliminating 600 feet of unnecessary elevation, saved twenty minutes on the average passenger one-way train trip and an hour for freight deliveries to New York State. Henry Truesdale, president of the railroad, explained,

This cut-off…is substituted for 43.2 miles of almost the first stretch of road built in the section. It followed the best route they could find for their purposes. It was an achievement—one of the many little pioneer railways which were the beginning of the superb networks of railways which now crisscrosses the Nation.

Consequently, the DL&W Railroad eagerly anticipated the economic impact the Nicholson Bridge would have on their bottom line.

The Nicholson Bridge was a part of the larger Clarks Summit-Hallstead Cutoff construction project devised by Henry Truesdale, who was looking for a way to shorten and straighten the railroad from Scranton to Binghamton, New York. Along with the Nicholson Bridge, a smaller replica, still huge by modern standards, was built nine miles north in the town of Kingsley, PA. This bridge is referred to as the Martin’s Creek Bridge, after the waterway over which it sits. Besides the two massive bridges, a 3,630-foot tunnel called the Nicholson Cutoff was built two rail miles south of Nicholson. The entire project was estimated to cost approximately $12,000 000, with the Nicholson Bridge itself accounting for $1,750,000.

With documents in hand and contracts secured, many men were needed for such a project to reach fruition, and a new work force was generated. Word spread, and Nicholson’s population grew from just about 900 to over 2,300, seemingly overnight. The little town was overrun by transplants to the area, all ready to work in 24-hour shifts. Yet, as the workers toiled relentlessly for four years, the townspeople came together to combat the difficulties of the lifestyle. The men worked tirelessly through unforeseen construction problems, like quicksand at pier locations. The women raised families with husbands gone for days at a time. However, the people persevered, and 1915 marked the completion of the project; it was certainly a sight to behold!

At the dedication ceremonies on November 6, 1915, Pennsylvania Governor Martin C. Brumbaugh compared the Tunkhannock Viaduct to the Walnut Lane Bridge over the Wissahickon Creek in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park. When Walnut Lane opened in December 1908, it was hailed as the largest concrete bridge in the state; its main span measured 233 feet long and rose 147 feet over the valley.

Quipped Brumbaugh,

You could put a dozen of Walnut Lane bridges under this monster and not notice them…This bridge should be named the eighth wonder of the world. As a matter of fact the old wonders of the old world do not begin to compare in the quality of genius with this splendid piece of engineering skill that spans your valley and crowns your city.

Many more men and women traveled to Nicholson to marvel at the bridge, such as Thomas Edison, Henry Ford and former President Theodore Roosevelt. The most memorable comment came from Theodore Dreiser’s 1916 travel biography, A Hoosier Holiday, in which he sums up his impressions of the bridge:

A thing colossal and impressive. Those arches! How really beautiful they were. How symmetrically planned! And the smaller arches above, how delicate and lightsomely graceful! It is odd to stand in the presence of so great a thing in the making and realize that you are looking at one of the true wonders of the world.

The bridge saw heavy use well into the 20th century; however, as the end of the anthracite coal era approached, the bridge became virtually obsolete for industrial use. Yet, it is still a marvel; because of the state-of-the-art drainage system, the structure has maintained its structural integrity and has remained open for tours and occasional train rides. Additionally, the township of Nicholson, in honor of the bridge and those who created it, holds a celebration annually. The Nicholson Bridge Day celebration that takes place on the second Sunday of September features handmade crafts, entertainment and food vendors.

The bridge has also been awarded many honors, including certification as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) for the bridge’s significant contribution to the development of the United States and to the profession of civil engineering. This is a very rare honor, as only 244 landmarks in the world have ever received the distinction. The viaduct, too, has been documented by the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER), which was established in 1969 by an agreement by the National Park Service, the ASCE and the Library of Congress to document historic sites and structures related to engineering and industry. The HAER affirms, “More than 50 years after its building, the Tunkhannock Viaduct still merits the title of largest concrete bridge in America, if not the world.” Truly, this manmade undertaking was an incredibly successful endeavor.

The Center wishes to thank John Romero, Josh Stull of the Nicholson Heritage Association, Barbara M. Grace, and Adam Prince for their assistance illustrating this article.

Sources:

- “2009 Tunkhannock Viaduct Excursion.” Steamtown National Historic Site. National Park Services, 20 July 2009. 9 Mar. 2010 <http://www.nps.gov/stea/parknews/2009-tunkhannock-viaduct-excursion.htm>.

- “Association launches campaign for bridge.” The Abington Journal. 16 Dec. 2009. 9 Mar. 2010 <http://www.timesleader.com/AbingtonJournal/community/Association_launche....

- Deloney, Eric. “Bridging the Past for the Future.” The Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 2000. 9 Mar. 2010 <http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/historic_bridge...

- “Endless Mountains Endless Hunt.”The Friendly Metal Detecting Forum.May 2006. 9 Mar. 2010 <http://metaldetectingforum.com/showthread.php?p=138966&highlight=endless....

- “Historical Markers: Marker Details.” Explore PA History. WITF, 2010. 9 Mar. 2010 <http://explorepahistory.com/hmarker.php?markerId=644>

- “History and Heritage of Civil Engineering-Tunkhannock Viaduct.”American Society Civil Engineers.9 Mar. 2010 <http://www.asce.org/history/brdg_thannock.swf>.

- “Lackawana Road Has its Cut-Off.” Wilkes-Barre Times 5 Oct 1915: 4.

- Lynch, John J. “Tunkhannock Creek Viaduct.” NortheastPennsylvania.com. Nicholson Area Library, 1976. 9 Mar. 2010 <http://www.northeastpennsylvania.com/NicholsonViaduct.htm>.

- “Millions for Efficiency.” Charlotte Daily Observer 4 Nov 1915: 4.

- “News of General Interest in the Secular World.” Herald of Gospel Liberty. 107.43 (1915): 1522.

- “The Nicholson Bridge.” The Nicholson Bridge: A Historical Site. RocketTheme, 2008. 25 Feb. 2010 <http://www.nicholsonbridge.com/>.

- “Nicholson Bridge.” Nicholson Heritage Association. Nicholson Heritage Association, 3 Feb. 2010. 25 Feb. 2010 <http://www.nicholsonheritage.org/index.php?p=1_5_-Nicholson-Bridge->.

- “Nicholson Celebrates Bridge.” The Times Leader. The Wilkes-Barre Publishing Company,2 Sept. 2009. 9 Mar. 2010 <http://www.timesleader.com/scrantonedition/news/Nicholson_celebrates_bri....

- “The Opening of the Nicholson Viaduct, 1915.” Explore PA History. WITF, 2010. 9 Mar. 2010 <http://explorepahistory.com/odocument.php?docId=199>.

- **”Origins of Town Names.” Northeast Pennsylvania. 1 Aug. 2007. 9 Mar. 2010 <http://www.nepanewsletter.com/towns.html>.

- Prince, Adam. “Pennsylvania’s Engineering Marvels - The Tunkhannock Rail Viaduct.” Gribble Nation. GribbleNation, 1 Apr. 2007. 9 Mar. 2010 <http://www.gribblenation.com/papics/eng/tunkhannnock.html>.

- Trencansky, Tom. “The Tunkhannock Viaduct.” New York Railroads. New York Railroads, 5 Dec. 2005. 9 Mar. 2010 <http://www.newyorkrailroads.com/Nicholson/>

- “Tunkhannock Viaduct.” Bridge Browser. HistoricBridges.org,26 May. 2007. 9 Mar. 2010 <http://www.historicbridges.org/pennsylvania/tunkhannock/index.htm >.

- “Tunkhannock Viaduct.” Bridge Hunter. Historic Bridges of the U.S., 26 Feb. 2007. 9 Mar. 2010 <http://bridgehunter.com/pa/wyoming/tunkhannock/>.