Boyertown Area Historical Society

I must have turned the wrong valve. There was a long drawn out hissing sound that frightened the women and children. Several of them jumped up and screamed and ran toward the stage. The curtain was down. I don’t know what happened next,” said Harry W. Fisher, the stereopticon operator, in The New York Times on January 14, 1908, after an infamous performance of The Scottish Reformation. When a tragedy occurs in any small town, there is always speculation about what could have been done to change the circumstances of despair, and often times, blame gets placed on whoever is still alive to bear it. It is possible that no one felt guiltier than Harry Fisher in the days after the Rhoads Opera House Fire, but it is impossible that any growing town felt lonelier. The loss of the Rhoads Opera House was felt on every street, at every home, and in every heart of Boyertown, Berks County.

The Night of the Performance

It was January 13, 1908, and members of St. John’s Lutheran Church were performing at the Rhoads Opera House in Boyertown. About fifty members of the congregation’s youth were busy prepping their lines and readying their make-up while 400 of their loved ones from the small, industrious town sat on the edges of their seats, waiting in anticipation for the third act of The Scottish Reformation: the execution of Queen Mary. Excitement was in the air, and the audience watched the drawn velvet screen while the actors set up the horrific scene of the monarch’s death scene.

After Fisher “turned the wrong valve,” cast members lifted the curtain to see what had happened, only to knock over a kerosene lamp, set on the stage for additional lighting. This started a small fire on the stage, but it was nearly extinguished. Unfortunately, when some of the men in the front row took the precaution of moving the tank of kerosene that fueled the footlights bracketed to it, its framework buckled, the fuel spilled and brought the small fire back to life. The audience reacted in hysteria, jumping up from their seats and running towards the nearest exits. Some of the sensationalist press of the time reported that men darted forward, picking up chairs, and assaulting men, women, and children in their flight for their own lives. Later clarifications of survivors’ stories showed that no one assaulted anyone; there was just the understandable panic in the midst of the fire. Children were scooped up under the arms of their parents who ran forward, turning this way and that, scurrying to find an opening.

Boyertown Area Historical Society

When spectators reached the doors, they found the greatest obstacle in their path to safety. The doors, sometimes falsely reported to have been bolted shut, opened inward. According to later claims in the January 14, 1908 issue of The New York Times, the doorkeeper had become so entranced in the performance that he had locked the doors to prevent further entrance and sat in a rear seat to watch the show. Actually only one of the doors had been locked and as soon as the fire was seen, an usher unlocked it. The sheer press of panicked theatre-goers attempting to leave created a bottle neck and their mass made opening the doors impossible. The greatest loss of life happened at the main doors.

While much of the audience sat in seats bolted to the floor, additional fold-up chairs had been set up and these turned out to be additional obstacles when the fire began as they were turned over and pushed around, creating a maze for the frantic audience. The doorway leading to Philadelphia Avenue had turned into a battlefield in general chaos caused by the flames, the smoke, and the panic. The fire escapes were unmarked and difficult to find in the smoke-filled building. Moreover, unlike modern fire escapes, they were window openings three feet above the floor level. Women found their long dresses hampered their escape. Glass, broken varnished pieces of wood, and eventually, bodies, littered the floor of the playhouse, all acting as props in this master play of disaster.

Amid the flames and the desperation, Reverend Adam M. Weber, pastor of St. John’s Lutheran Church, shouted for patience and unity. The minister had been one of those who tried to move the kerosene tank, but was badly burned and injured in the attempt. No one heard him or attempted to help, as he called out to his children, his family, and the congregation. Hours later, he would be found amongst the survivors, crying in sorrow for the loss of one of his young daughters.

One door was finally splintered down, causing a waterfall of stampeding patrons to fall to their death or stumble down the staircase. Rescuers would later be horrified to find that around the head of the four-foot wide staircase, bodies of the dead were piled five or six deep. “It was a terrible sight, and I shall carry the recollection as long as I live,” said survivor Reuben W. Stover, days after the tragedy in the January 17, 1908 issue of The Cranbury Press. “Once the crowd began to fight its way toward the doors, no power on earth could have saved all the lives, but I believe that, if the men had not lost control of themselves, the loss of life would have been very small.”

Battling the Blazes

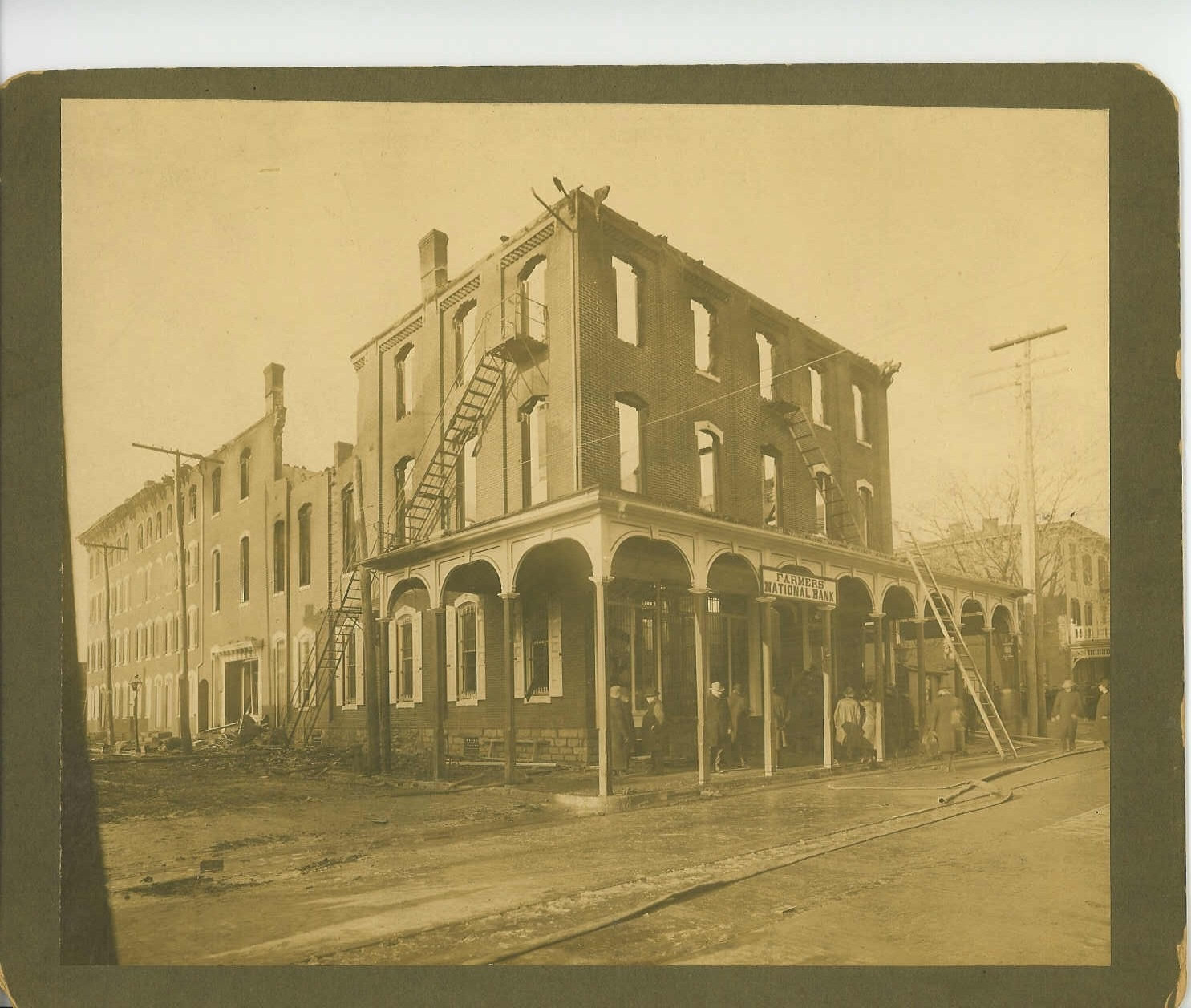

Despite the mayhem and confusion, more than half of those held captive were able to make it out of the smoke-filled blaze. Some people rushed out a secluded set of stairs hidden behind the stage or climbed to break out of window raised three feet high, holding their heavy dresses and attire in hand. Others were helped out of the fire escapes and pulled out of the crowd at the doorway by local residents. The Boyertown Volunteer Fire Department arrived five minutes after the alarm had sounded and began hosing down the house fire. The Keystone Fire Company attempted to respond to the blaze, but lost control on their way and damaged their equipment when they ran into a tree. The Friendship Hook and Ladder Company also responded to the call, but its time of arrival is unknown. The neighboring Pottstown Fire Department did not arrived until after 11:30 pm to help, but the flames could not be quenched. Shortly after midnight the roof of the Rhoads Building fell in. The fire was brought under control at about 4:14 a.m. on January 14. A crowd gathered around the sight of tragedy, questioning officials and screaming for their loved ones trapped inside. The first body was not brought out until 8:30 am.

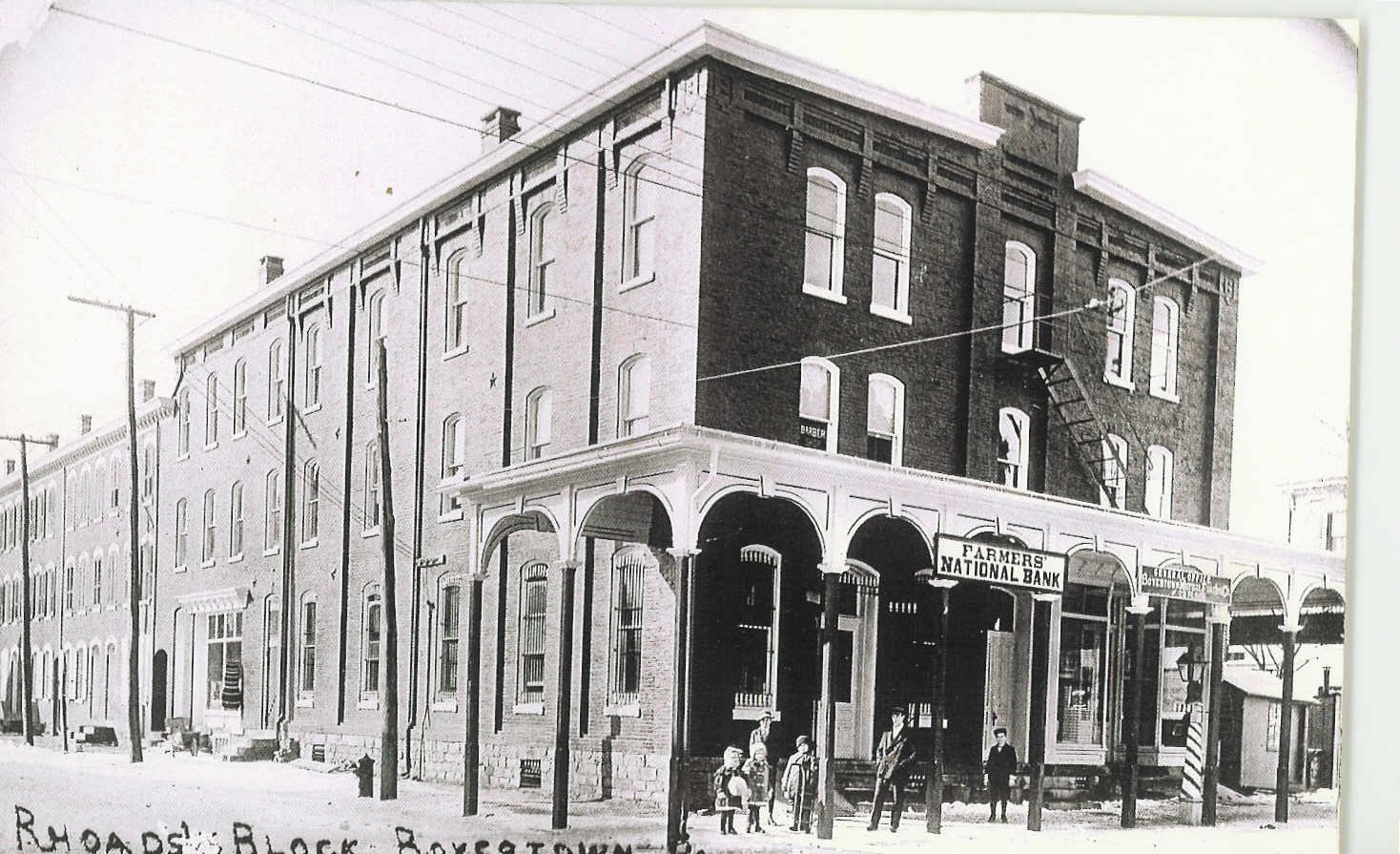

The Rhoads Building was three stories high and comprised of various businesses. The first floor housed the Farmers’ National Bank and a hardware store. The second floor held the auditorium. The third floor was occupied by a lodge hall used by various civic and fraternal groups for meetings. In the rear of the bank were four large dwelling houses, rented to families. The January 17, 1908 issue of The Cranbury Press reported that all areas of the building had been destroyed in the fire. 170 people were killed in the fire; of those, 25 could not be identified.

A Town in Mourning

Boyertown could never have suspected such a tragedy to befall them. Charles Spatz, editor of The Berks County Democrat, had only weeks earlier claimed that in Boyertown, “The death rate was small and the birth rate was large. No epidemic visited us and none of our people met with any serious misfortune, for all of which we are duly thankful and proud.” Now, the town faced the stark reality that ten percent of its population had been lost in less than a night, as stated in WFMZ’s documentary, The Rhoads Opera House Fire: The Legacy of a Tragedy.

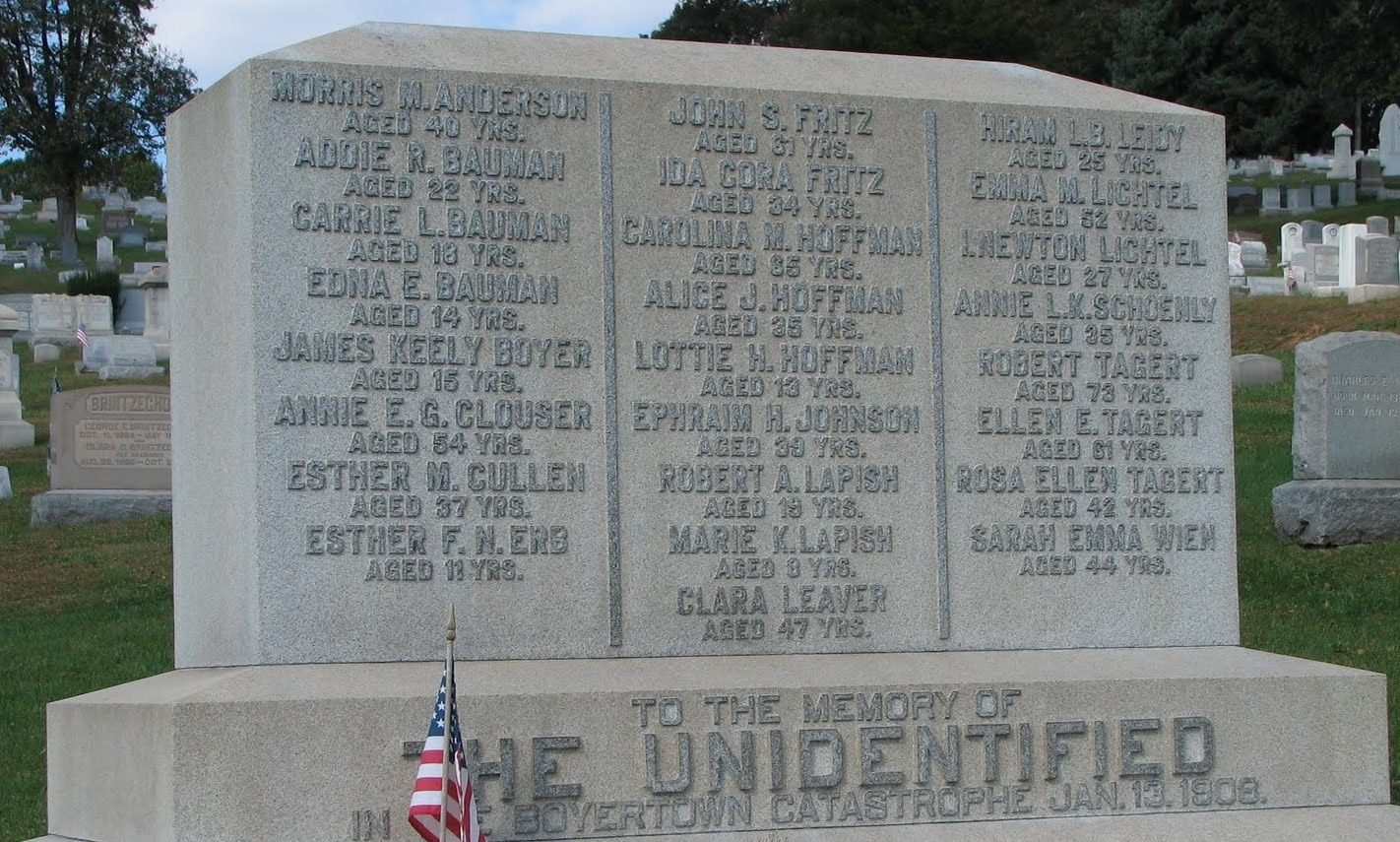

One male for every three females had been a victim of the fire. The coroner noted that only the upper portions of the victims’ bodies had been incinerated by the flames. The lower portions of the deceased had remained intact, clear evidence that the fires had swept over the wedged- in- audience, killing them while trapped against one another. One hundred seven new graves were dug in nearby Fairview Cemetery. This included a common plot of separate graves for the twenty-five victims who could not be positively identified. Others were buried in various cemeteries around the area, some as far away as Philadelphia and Lancaster, according to Lindsay Dierolf of the Boyertown Historical Society.

For those who could not be positively identified, individual graves were dug and a common marker erected in their memory. Burgess Daniel Kohler of Boyertown noted in The New York Times on January 14, 1908, “Many of the men who perished in the fire were employed in the Boyertown Casket Company. The majority were carpenters employed in the making of coffins. Many a poor fellow unconsciously labored over the coffin in which he will be buried.” The borough president ordered that all saloons be shut down because of the influx of visitors and spectators arriving to witness the aftermath of the disaster.

Grief, Graves, and Guilt

Daniel Kohler appointed a relief committee that met three times a week to deal with the aftermath of the crisis and aid in making repairs. According to the Pennsylvania Department of Labor and Industry, Philadelphians had bonded together and raised relief funds of $18,000.

The total contributions given to the relief committee totaled $22,075.84. The largest contributors were made by local residents. Calvin Fegley, treasurer of Pottstown, had contributed $2000. The Eishenlor Brothers Cigar Factory had given $1000, and the mournful Boyertown Casket Company gave $600. Editor Spatz said, “We sorrow for our dead in solitude,” as remembered in The Boyertown Times on April 3, 2008.

The remaining citizens of Boyertown expressed their grief through silence or anger. At the coroner’s hearing, Deputy Factory Inspector Harry Bechtel of Pottstown testified that the opera house’s fire escapes had only been added on after the building had been built. The building’s owner, Dr. Thomas J.B. Rhoads, had only installed the escapes after much prodding and with great reluctance. Dr. Rhoads was arrested afterwards for criminal negligence.

Though the play’s copyright owner and director Harriet E. Munroe was not present, enraged families believed that she shared in the blame of the Rhoads Opera House tragedy, and wanted to see her punished. Frank Moyer, a former commissioner who had lost his daughter in the fire, was so distraught that he brought a lawsuit against Mrs. Munroe. No legal charges, however, were filed against her.

Boyertown Tragedy Touches All

News of the fire and loss of family reached across the United States. The Rhoads Opera House Fire was even covered by The Omaha Daily Bee in Nebraska. The story made front page news, spanning for several pages, and was covered two days after the event occurred. “The fire’s impact was sobering, immediate, and far-reaching,’’ author Mary Jane Schneider wrote in A Town in Tragedy,’ a biographical/historical account depicting the fire and its aftermath. “Boyertown learned a tragic lesson. Philadelphia learned. The whole country learned.’’ The flaws in the construction and structure in the opera house and the deaths that occurred because of those overlooked defects prompted new legislation for Pennsylvania.

The Rhoads Opera House Fire sadly echoed that of the Iroquois Theatre Fire which had occurred five years earlier under similar circumstances, but with a shocking mortality number of 602 people. Prompted by grief and awareness, on May 3, 1909, a little over a year after the fire, Governor Edwin Stuart of Pennsylvania signed the state’s first fire law, and the entire nation followed suit.

In particular, Act 233 addressed the installation of safety features in buildings, such as doors which opened outward, more than one exit from second floors, properly lit exterior doors from backstage areas, easily accessed and visibly marked fire escapes, fire extinguishers, and the requirement that all door exits were to remain unlocked throughout the performances. Act 206 also required fireproof booths for projector machines and stereopticons, remembering the hiss that caused the hysteria. No one from Boyertown will ever forget the fire, and neither can the nation. The Rhoads Opera House fire is the ninth deadliest fire in the history of the United States and was the inspiration that prevented further lives lost to flames.

Remembering Those Who Were Lost

On the 100th anniversary of the fire, bells tolled at St. John’s Lutheran Church 170 times, once for every person that was lost. During the Service of Remembrance, Reverend John G. Pearson said in The Boyertown Times on January 17, 2008, “The ripples of the event still touch us today. When you and I see fire safety codes in buildings, we have to think back to the Opera House.” A state historical marker was unveiled to the public on June 28, 2008 at Fairview Cemetery in Boyertown, commemorating the victims of the 1908 fire. Even local playwright, Kathy Galtere, wrote a musical about the fire called Unclaimed Carriages. It was performed by Boyertown Junior High West and performed days before the anniversary. A second play was also staged and a concert was held, for which original music was commissioned. Lindsay Dierolf recalls that the Boyertown Area Historical Society “undertook massive amounts of research” in preparation for the commemoration. They held at least ten events and activities during an 18-month period around the anniversary to “memorialize the event and its victims.”

Although the building was called an opera house, no documentation can be provided that proves that an actual opera was performed there. The term most likely refers to a public auditorium used for plays and performances. The owner of the building, Thomas J. B. Rhoads, promised to rebuild and he did. The new architecture was constructed to resemble the former Rhoads Building and was built on the original stone foundation. The new interior of the building was made from poured concrete forms for floors, walls, and stairways. Today, the building still stands on the corner of East Philadelphia Avenue and South Washington Street and bears a plaque in memory of those who were lost more than a hundred years ago. The building currently holds a realty business, apartments, and a dance studio.

Superstition at the Site

A lot of mystery and superstition still surround the site of the fire, then and now. Weeks following the fire, many residents reported hearing screams from the burned down site. One woman even claimed that her house was being taken over by spirits from the tragedy. Days later, an elderly man had to removed by force from the ruins when he claimed that his deceased wife had told him to meet her at a certain spot to talk to her.

Presently, stories still circulate about various screams and apparitions of opera house patrons. A local resident who currently lives across the street from the site of the fire said, “I’ve lived here my entire life and have heard so many ghost stories about the building. One old resident of the apartments there swore that every year around the same time a woman dressed in fine clothes would walk through the apartment, proclaiming to be late for the play.” Another Boyertown resident has heard various stories about the dance studio: “Some of the younger girls would never practice in one of the dance rooms, claiming it was full of ghosts. I don’t know whether it was because they had heard stories, or if they had truly seen something.” Whatever it is, haunted or not, it will always remain tragically memorable.

The Flames Burn Forever

Unfortunately, the Rhoads Opera House Fire had to occur in order to prevent other disasters from happening. It is because of the 170 victims of the fire that new fire regulations and safety laws were created. It is because of the families and loved ones of those who were lost that action was taken and flames were extinguished. When a performance, a play, a movie, an exhibit, is given today, no member of the audience has to worry about becoming captive to a deadly scene meant for the newspapers. Audiences, cast members, and any occupant of a building can be assured that they are protected by the necessary precautions in the case of a fire. The Rhoads Opera House audience members were not so fortunate. The memory of them and of their tragedy still burns on.

The Center would like to thank the Boyertown Area Historical Society for their assistance illustrating this article.

Sources:

- “1908 Pa. Opera House Tragedy Ushered in Fire Safety Rules.” Insurance Journal. Web. 11 Oct. 2010. <http://www.insurancejournal.com/news/east/2008/01/15/86413.htm>.

- Berks County Democrat [Boyertown] 10 Apr. 1909.

- The Cranbury Press [New Jersey] 17 Jan. 1908.

- Deirolf, Lindsay. Personal Communication to Alan Jalowitz. 4 Apr. 2011.

- Gehringer, Martha J. “For Whom The Bell Tolls.” The Boyertown Area Times 17 Jan. 2008.

- Greater Boyertown: A Special Kind of Place. Boyertown: TriCounty Chamber of Commerce.

- The New York Times 12 Sept. 1908.

- The New York Times 14 Jan. 1908.

- “Opera House Historic Marker Placed in Fairview Cemetery.” The Boyertown Area Times 3 July 2008.

- “Rhoads Opera House Fire.” Boyertown Area Historical Society Home Page. 12 Oct. 2010 <http://www.boyertownhistory.org/>.

- “Rhoads Opera House.” Welcome to Tri- County Paranormal. 17 Oct. 2010 <http://www.delcoghosts.com/rhoads_opera_house.html>.

- Schneider, Mary Jane. A Town in Tragedy. Boyertown, PA: MJS Publications, 1992.

- Schneider, Mary Jane. Midwinter Mourning: The Boyertown Opera House Fire. Boyertown, PA: MJS Publications, 1991.

- Schneider, Mary Jane. A Town in Tragedy. Boyertown, PA: MJS Publications, 1992.

- VanDyke, Diane. “Boyertown Opera House Fire.” The Boyertown Area Times 3 Apr. 2008.

- WFMZ. The Rhoads Opera House Fire, The Legacy of a Tragedy. Pennsylvania, 13 Jan. 2008. Television.