Described alternately as Philadelphia’s “eyesore,” and a place that “oozes Philadelphia character,” Veterans Stadium was a landmark in its time. From 1971 until 2003, “The Vet’—as it was commonly known—was home to two of the biggest franchises in the city of Philadelphia, the Phillies and the Eagles. Veterans Stadium represents much more than a sports venue; it represents the heart and soul of a city, the place with the most rabid fans in the nation, and the stadium that struck fear into opposing players before games even began. Veterans Stadium created lifelong memories in the Philadelphia sports world, and left a longstanding impression on everyone privileged enough to attend a game there.

Veterans Stadium opened in 1971; the idea, however, came about in the early fifties, when both the Phillies and the Eagles played in Connie Mack Stadium. Connie Mack Stadium—or Shibe Park as it was originally named—was opened in 1909 and housed both the Philadelphia Athletics and Phillies, as well as, later, the Eagles. The Phillies bided their time in Connie Mack Stadium, but the Eagles cut ties with the stadium in 1958, opting to play their home games at Franklin Field—a larger venue located on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania. In the early sixties, many locations had been proposed for the new stadium. The residents of Philadelphia spoke out against every proposal, and Phillies owner Bob Carpenter threatened to move the team to New Jersey.

Philadelphia City Council President Paul D’Ortona endorsed the stadium proposal at Broad Street and Pattison Avenue in South Philadelphia, roughly ten miles south of Connie Mack Stadium. The proposal had suggested a “multi-purpose” stadium for both the Phillies and Eagles to use. This type of design was becoming a trend among several professional teams, with one of the earliest being R.F.K. Stadium in Washington, D.C. For Philadelphia, influence could be seen in Cincinnati, Ohio’s Riverfront Stadium and the in-state Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh. Both of these stadiums were of the “donut” multi-purpose stadium design—circular designs with seating around the entire field. Veterans Stadium would ultimately adopt this donut as well.

Legislators and the city later changed their tunes to endorse the new site behind D’Ortona. Democrats, Republicans, and the City Planning Commission backed the project. In 1964, city council approved the location and a $25 million bond for the stadium passed by a vote of 233,247 to 192,424. This location would soon become a hub of sports nationwide along with The Spectrum, home to the Philadelphia Flyers and 76ers from 1967. One group, the Combined Citizens Committee Opposing the Proposed Stadium Site in South Philadelphia, opposed the stadium proposal. The group, however, later lost their suit in Common Pleas Court.

With the bond vote passing, the stadium needed a name. Dozens of potential names surfaced. War veterans proposed War Veteran Stadium—a name strongly opposed by the large population of anti-war activists in the sixties. City councilman John B. Kelly Jr. considered the name “dull, sedate, and aged.” Kelly went on to add that “Too many people already think of Philadelphia as a cemetery with lights.” Eventually, the name was proposed as Philadelphia Veterans Stadium, which passed in a city council vote in March, 1970, due to heavy pressure from several local veterans groups.

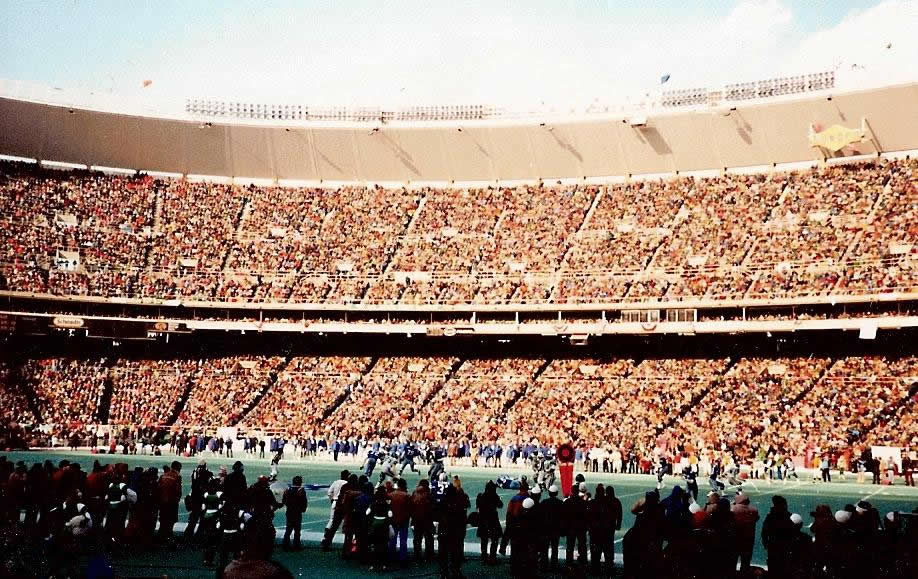

While the stadium had a name and financing, the city eventually turned to Hugh Stubbins & Associates to lead the architecture behind the project while actual construction fell to McCloskey & Co. The stadium had a somewhat complicated design. Packed within the 62,000 seat structure were seven different seating levels. The 100 level seats surrounded only part of the stadium, while the 200 and 300 level boxed seats surrounded the entire facility. Together, these three levels comprised the “lower stands.” In these lower stands, tickets were generally higher priced and saved for high-profile guests. The next level, known as the 400 level, housed the media and press operations. The 500, 600, and 700 levels were then comprised of more general admission seating for fans. It was in these upper levels that fans would gain their fierce reputation.

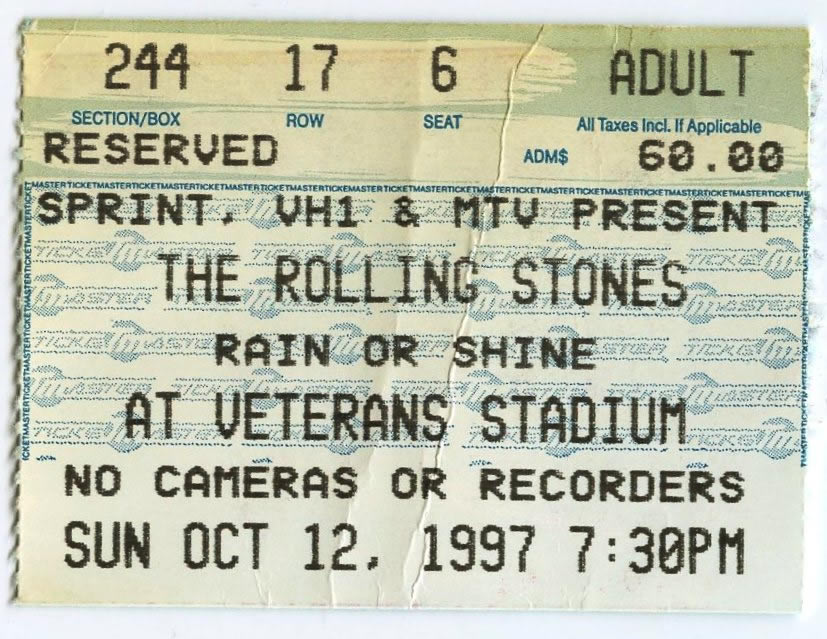

Throughout all levels of the stadium, fans were met with a multitude of restaurants and other attractions. Visually, the stadium had other features to make it pleasing to the eye. Found in numerous locations were statues of baseball players stealing bases or taking a big swing and football players running down the field or making a crucial tackle. None of these statues were modeled after a particular player or event, but were left nameless to perhaps represent all of Philadelphia’s athletes. One sight which was easily identifiable was the statue of former Athletics owner Connie Mack, which once stood at Connie Mack Stadium. While other statues were nameless, Mack’s was clearly identified, showing all fans an important Philadelphia sports figure who had won five World Series titles with his team. These were just some of the scenes fans enjoyed in the new stadium. For several fans who encountered the stadium, it was a spectacular sight. One fan shared, “It was impressive. There were so many seats, restaurants everywhere, statues outside, and excitement beyond anything I’d ever felt.”

Prior to its opening, the stadium was met with several problems. Perhaps the most notable occurred in 1969, when stadium builders were accused of using weaker materials than specified. When the case went to trial, then-District Attorney Arlen Specter needed only one witness to convict the company on the charges. The trial eventually moved to the State Superior Court, where the charges were dropped. Similarly, stadium coordinator Harry Blatstein was caught in a bribery scandal with seat suppliers. He ultimately resigned from his position amidst the scandal. Although faced with these problems, Veterans Stadium opened on April 10, 1971. The first game saw the Phillies playing against the Montreal Expos in front of a crowd of 55,352—a game when legend was born in Philadelphia; a legend which would have a 33 year history of both success and heartbreak while always being a unique experience for every person to experience it.

Opening day in the stadium left the national media awestruck. Outlets raved about the beauty and those who experienced it firsthand knew that the stadium was an innovator in its time. The New York Post claimed that no more bad jokes could be made about Philadelphia, while New York Times writer Bill Wallace remarked that the stadium was “the best I’ve ever seen.” When Expos manager Gene Mauch arrived for that first game, he said it was “the best new park in baseball.”

During that first season at Veterans Stadium, the Phillies set a team attendance record with over 1.5 million total spectators despite finishing nearly 30 games under .500. Over the years, the luster wore off but the stadium remained a crucial part of the city. The players loved that their stadium was envied by many and they thought the facilities were much better than previous venues. John Denny, who played three seasons with the Phillies in the 1980s said: “Even when I was with the Cardinals and we came to the Vet, I always wanted to be a Phillie because of the stadium and the environment. Even at the end, it was better than some of the new stadiums. It had a tremendous history.”

This environment is part of what made the stadium so memorable for fans and players alike. Perhaps the most noticeable attraction is the Phillie Phanatic. With its fuzzy green fur, long snout, tongue sticking out, and its large size, the Phillie Phanatic easily became a fan favorite. Replacing Phil and Phillis—two siblings who wore 18th century clothing—the Phanatic made its debut in 1978. A presence in the stadium, the Phanatic could often be found trying to distract opposing players, engaging in sideline antics on his all-terrain vehicle, or just roaming the stands trying to make a new friend. No matter what the Phanatic was doing, the friendly green creature made the stadium a welcoming environment to fans.

While not being entertained by the Phanatic, fans could turn their ears to the announcer’s booth and listen to Merrill Reese and Harry Kalas. Both announcers carried unique voices easily identifiable for both the Eagles and Phillies respectively. While Reese’s calls were only available on radio, Kalas’ calls filled the stadium for every Phillies game. Kalas’ notable “outta here!” call for Phillies home runs almost served as a cue for fans, as the stadium would erupt after those words. All of these figures added a unique character to the stadium, whether it was the fun antics of the Phillie Phanatic or the legendary calls of Kalas and Reese which rang throughout the stadium. These figures, however, would carry little value if it were not for the fans that filled the stadium on a regular basis.

Passionate Philadelphia fans filled all levels of the stadium; the fans in the 700 level added to the stadium’s fierce reputation. Their passion and loyalty to their teams is often noted by many. While both the Phillies and Eagles did not have great success during the stadium’s lifetime, fans consistently filled the seats to support their team. One fan commented, “The Vet meant sitting in the freezing cold on Sundays and watching the Eagles constantly disappoint or sitting in the upper deck with the sun beating down on you in July wondering if the Phillies could possibly be any worse.”

This type of commitment is what is most noted by the players and reporters who passed through Veterans Stadium. Former Eagles quarterback Ron Jaworski praised the 65,000 screaming fans that stood behind him and credits them for giving both teams “a true home field advantage.” The energy found in that stadium was often hard to match. “Standing on that field, it felt very little like anything else,” noted sportswriter Peter King.

Yet while the stadium was noted for the energy and support that filled it on game day, the stadium also had a negative reputation. Writer John McClain described the fans as “passionate and knowledgeable, and they can be extremely loyal, but they also can be unbelievably cruel and obscene.” This was nothing new to Veterans Stadium, as Eagles fans are noted for booing Santa Claus at their former Franklin Field home. When certain opponents were playing in the stadium, the behavior became especially difficult to deal with. During a 1989 game against the Dallas Cowboys, Eagles fans filled the stadium and proceeded to target opposing players and coaches with snowballs, beer, and anything in reach. In 1999, Phillies fans fell under criticism during a game against the St. Louis Cardinals when they threw batteries at former Phillies draftee J.D. Drew.

Perhaps the most alarming quality of these fans was when they would cheer upon an opposing player getting injured. One defining moment of fan history was when Dallas Cowboys’ receiver, and future Hall of Fame player, Michael Irvin was hit and lay motionless, potentially paralyzed, on the ground for 20 minutes. The fans proceeded to cheer, with some acting downright rowdy. This incident put Philadelphia fans on the national stage and became a defining moment in stadium history. Former NFL coach Bill Parcells would later go on to call the stadium a “banana republic” in response to the rowdy behavior of the fans in the stadium.

This type of behavior led to another amazing moment in stadium history, the creation of an in-stadium jail, commonly referred to as “Eagles Court.” The court was installed in 1998—a result of several fistfights breaking out during a nationally-televised Eagles game. The move made waves, as Veterans Stadium was the only arena in the country with a courthouse, a move which seemed necessary given fans’ behavior. Eagles Court became an oft-criticized feature of the stadium, and is used constantly to nationally antagonize the fans of the city. Proponents argued that the offenses were typically very minor, and the threat of a jail calmed down the crowds significantly. Then councilman John F. Street (who would go on to be mayor of Philadelphia) said that the court was “Too soft, too swift, too unfair to everyone else in the city who gets arrested.”

While the fans were negative at times, their passion and loyalty was ever present in the few successful moments the teams had experienced during their tenures. 1981 saw the Eagles advance to their first Super Bowl with a win over the rival Dallas Cowboys in the conference championship game. Fans stormed the field following the victory. Former Eagles general manager Jim Murray described that it felt as if “the stadium was on fire.” Perhaps the most notable victory in Veterans Stadium history came one year earlier, when the Phillies won their first World Series title.

The Phillies had battled the Kansas City royals to take a lead in the series, three games to two. On October 21, 1980, the series returned to Philadelphia for game six. The Phillies went out to an early three run lead. In the final inning, the Royals had the bases loaded with two outs. On what turned out to be the final pitch of the game, pitcher Tug McGraw struck out batter Willie Wilson. Veterans Stadium erupted for the Phillies’ first championship in team history. Announcers remained silent, allowing the elated Veterans Stadium crowd provide all of the necessary sights and sounds. In describing the moment, one fan who was present at the stadium that night said, “It was the best sports experience of my life and I don’t think that will ever change.”

Over the next two decades, both the Phillies and Eagles saw marginal success, but never achieving what they had during the early 80s. It was also during this time that the stadium began to fall into disrepair. The stadium’s Astroturf became old and worn, posing a safety hazard to players in both football and baseball. Even later replacements faced similar hazards. In its later years, rats had become a problem throughout offices located in the stadium. Former Eagles assistant coach Jon Gruden noted that “cats are everywhere,” which was done in an effort to combat the rat problem.

Even the players began to notice how outdated the stadium had become. “It’s nasty, it’s filthy, it’s dirty, it’s hard…it’s horrendous,” explained former Eagle defensive back Troy Vincent. Several players sustained injuries, mostly on the seams necessary to make the stadium suitable for both baseball and football. In 2001, a preseason game between the Eagles and Baltimore Ravens was cancelled due to the condition of the field. As a result, both the Eagles and Phillies lobbied for new venues to replace the aging Veterans Stadium.

Following the 2002 NFL season and the 2003 MLB season, both the Phillies and Eagles moved to separate, state-of-the-art venues tailored specifically to their sports. Each multi-million dollar stadium was specifically designed for each sport, abandoning the economical multi-purpose stadiums of the past. After the final Phillies game in September, 2003, the stadium had a final goodbye ceremony, featuring several former players and Philadelphia sports figures. Following the closing of the stadium, everything that could be sold, was. Over 10,000 seats were sold out of the old stadium, with several thousand remaining. Former players, coaches, and sports figures paid one last visit to the stadium before its implosion. While all who experienced the stadium, from players to fans, recognized it as a dump, several stood proudly behind it saying, “It was a dump, but it was our dump.”

Ultimately, the decision was made to tear down the stadium. On the morning of March 21, 2004, Veterans Stadium was imploded in a time of 62 seconds, with thousands of players, coaches, and fans present. The sight proved emotional for many, as workers, players, and fans spent several years of their lives in the stadium. Mike DiMuzio, the Phillies Director of Ballpark Operations said, “From day on to the last day, I’ve been at the Vet…I shed a tear when it came down. I shed a few tears before it came down.”

Today, the land upon which Veterans Stadium once stood serves as a parking lot for events at Lincoln Financial Field and Citizens Bank Ballpark—the new homes to the Eagles and Phillies respectively. Plaques and markers surround the lot, sharing the history of the stadium. Within the lot itself are markers noting each base, the pitcher’s mound, and the goal posts’ locations in the former stadium.

Veterans Stadium provided millions of people with unforgettable memories. From watching the Eagles advance to their first Super Bowl to the Phillies bringing a true championship home to Veterans Stadium, the memories are endless. Although the stadium is gone, the memories will live on in the minds of everyone privileged enough to enjoy some time in the stadium. As Phillies Public Relations Director Larry Shenk shared on the occasion, “We lost the building, but we won’t lose the memories.”

Sources:

- Didinger, Ray and Robert S. Lyons. The Eagles Encyclopedia. New York: Temple UP, 2005.

- Eichel, Larry. “Everything Must Go!” Philadelphia Inquirer. 26 Sept. 2003, City-D: A1.

- McClain, John. “Irvin Incident Shows How \Low Philadelphia Fans Can Go.” Houston Chronicle. 15 Oct. 1999, Sports: 10.

- Merron, Jeff. “It’s Hard to Say Goodbye.” ESPN.com. 2007. ESPN Internet Ventures. 13 Jun. 2011 <http://espn.go.com/page2/s/ballparks/veterans.html>.

- Nicholas, Peter. “Street Assails Eagles Court.” Philadelphia Inquirer. 29 Nov. 1997, City: B1.

- Philadelphia Eagles: The Complete History. Prod. Peter Frank. NFL Films, 2004. DVD

- “Philadelphia Phillies Attendance, Stadiums, and Park Factors.” Baseball-Reference.com 2000-2011. Sports Reference LLC. 11 Dec. 2009. <http://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/PHI/attend.shtml>.

- “The Phanatic makes his debut.” Phillies.com Community. 2001-2011. MLB Advanced Media. 11 Dec. 2009 <http://mlb.mlb.com/phi/community/phi_community_phanatic.jsp>.

- Santoliquito, Joe. “Veterans Stadium Comes Down” Phillies.com 21 Mar. 2004. MLB Advanced Media. 11 Dec. 2009 <http://philadelphia.phillies.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20040321&conte....

- Westcott, Rich. Veterans Stadium: Field of Memories. New York: Temple UP, 2005.