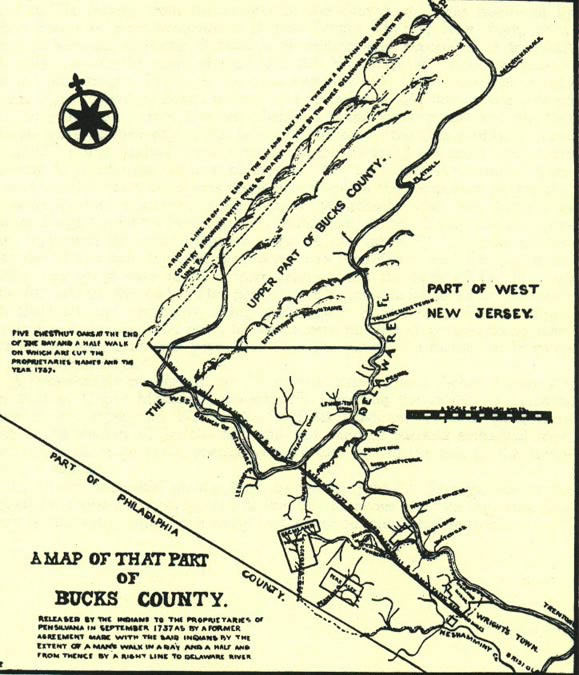

Stories of Native American interaction with white settlers are often marred by tears and bloodshed. Endless stories exist of natives mistreated or taken advantage of, coerced by alcohol or force. The Walking Purchase of 1737 was a betrayal without bloodshed or coercion; there was no massacre like the Battle of Kittanning, no forced march leaving a trail of tears. Despite its bloodless nature, the Walking Purchase was among the most devastating betrayals ever dealt to the Lenape, the natives who lived on the land taken. Some would call it more diplomatic compared to other white land grabs, and some would say it was civilized for its lack of bloodshed, but ultimately it is remembered as one of the most blatantly underhanded deals ever made by the whites. With little more than the honor of the late William Penn, a doctored, or perhaps entirely forged, document from 1686, and a hideous abuse of the wording within the document, the state of Pennsylvania acquired land bordered in the East by the Delaware, and by two lines in the west, one extending almost parallel to the Montgomery and Bucks County borders for about 66 miles where it reached the north side of Pocono Mountain, and another at a right angle to it, running until about five miles south of the Lackawaxen River. All in all, nearly 1,110 square miles were taken from the Lenape.

It is generally imagined that treaties between whites and Native Americans involved easily fooled natives giving away land, addled by alcohol or unaware of the ramifications of what they signed. The Lenape leaders involved with the Walking Purchase had no such handicaps. In Albert Meyers’ collection of some of William Penn’s works, William Penn, His Own Account of the Delaware Indians, Penn wrote, “he will deserve the Name of Wise, that Outwits them in any treaty about a thing they understand.” Tremendous effort was put into the deceptions that finally led to the signing of the 1737 Walking Purchase, actually a confirmation of an old, vague, and most likely fabricated treaty allegedly made in 1686.

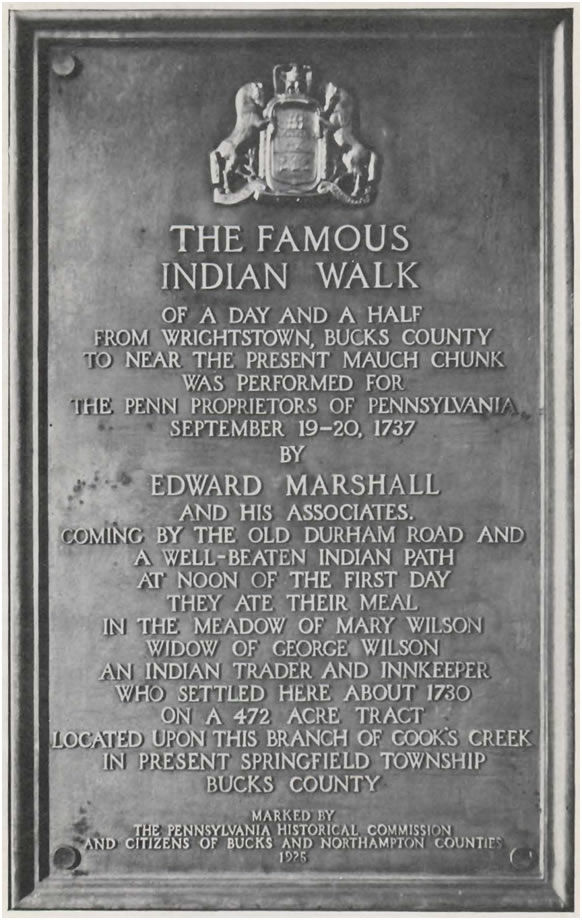

According to Steven Harper’s Promised Land, the 1686 treaty gave the settlers claim to land north of the previous treaty’s boundary line between the Neshaminy and Delaware rivers for “as far as a man could walk in a day and a half.” On September 19, 1737, three strong runners, James Yeates, Edward Marshall, and Solomon Jennings, began, in the words of Lenape interpreter Moses Tetemie, “what ye Indians call ye hurry walk.” The native spectators noted the quick pace and unexpectedly direct route the three were taking, and according to W.W.H. Davis, “showed their dissatisfaction at the manner in which the walk was conducted, and left the party before it had been concluded.” The approximately 65 mile “hurry walk” proved so grueling that only Edward Marshall managed to complete it, who Davis writes, “threw himself at length on the ground, and grasped a sapling which marked the end of the line.” Marshall’s athletic feat, combined with liberal interpretation of how the boundary line should be drawn to the Delaware River, took from the Lenape an area slightly smaller than Rhode Island.

Pennsylvania’s relations with the Lenape prior to the purchase were often considered an exemplary exception to the norm. Perhaps as part of William Penn’s Holy Experiment, it was believed that there existed a sort of “Peaceable Kingdom” in Pennsylvania, where natives and colonists walked amongst each other as brothers or friends. Though the good relations were often exaggerated, the perception of William Penn as fair and tolerant in his dealings with the Lenape was almost universal. Though he was technically already in possession of the land, Penn made a point of purchasing the land from the natives who lived there. After several treaties the Lenape deemed favorable, as well as making memorable gestures of friendship to the native leaders, Penn gained an almost mythic reputation amongst the Lenape. Both natives and colonists were willing to believe in Penn’s vision for a Peaceable Kingdom. This vision of harmony would later be painted in numerous variations by the minister and painter, Edward Hicks.

After William Penn’s death in 1718, charge of Pennsylvania fell to his three sons and his agent in the Land Office, James Logan. Richard, John, and Thomas Penn did not share their father’s idealistic hopes for the natives, but they certainly shared his problem with debt. In 1734 Thomas Penn, who was in Pennsylvania at the time, received a letter from his two brothers who according to Harper wrote, “we are now at the Mercy of our Creditors without anything to Maintain us.” With an ever-growing need to make money and no visions of a Peaceable Kingdom to stop them, Thomas Penn and James Logan abandoned the late William Penn’s policy of purchasing Lenape land before considering it available for proprietors to purchase in favor of the more profitable policy of ignoring Lenape ownership wherever convenient. This change in policy opened up vast tracts of land to sell in hopes of alleviating the Penn debts, but it did nothing to actually remove the Lenape from the lands in question.

The Penns’ land, regardless as to whether or not it could be sold, would not be profitable until the Lenape agreed to give it up. Since the reputation of Pennsylvania’s fair dealings with the Lenape had served well in the past, and the relative nonviolence of their relations was not something that Thomas Penn or James Logan wanted to upset, it was resolved that the lands in question would be somehow purchased from their native owners. Despite this being superficially the same method used to extinguish native rights to land that William Penn used, there was a stark difference between the mindset of father and son. Thomas’s father intended to make fair trades for the land; Thomas simply wanted to get the land by whatever means necessary, a purchase being the most convenient.

This purchase proved to be much harder to make than expected; the Lenape negotiators, led by the Sachem Nutimus, understood their land’s value. Nutimus recognized the position of strength they held over the desperate Thomas, and refused to sell their land for any price Thomas Penn could pay. After the first round of negotiations, Thomas scrambled to find some other means of convincing the shrewd Lenape to part with the land cheaply, and finally discovered that there had been additional negotiations in 1686 between his father’s representatives and the Lenape for land north of the previously made 1682 purchase that granted land as far north as Wrightstown. Harper wrote of the negotiations, “The best documentation they could find was ‘an unconsummated draft’ of the 1686 transaction… this 1686 purchase was aborted.” It was absolutely nothing legally, but altered sufficiently and presented to an audience that could not read, it would be the key to the Lenape lands.

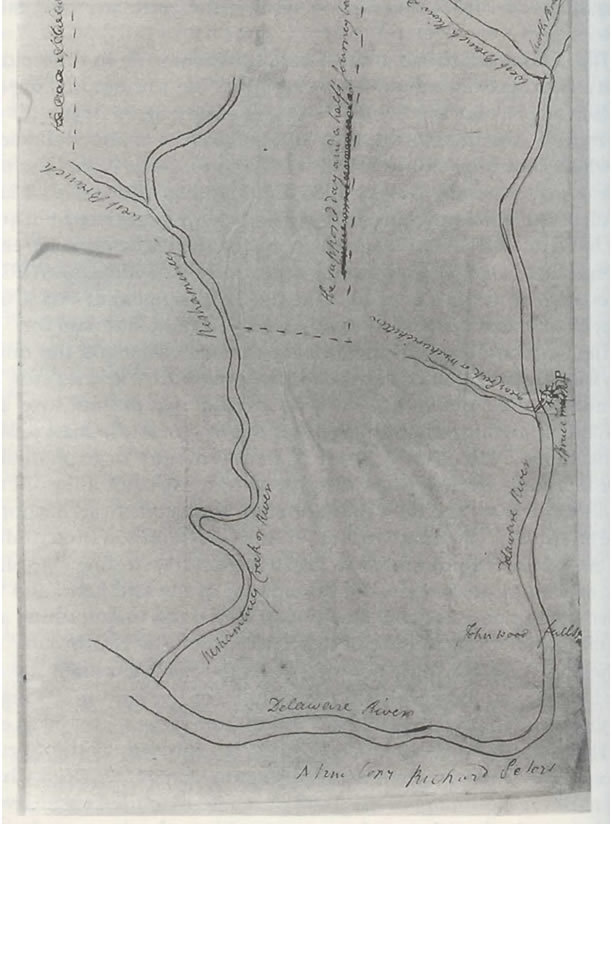

The old document, were it valid, granted Thomas’s father land north of the 1682 purchase to a distance “as far as a man could walk in a day and a half.” By the standard measurements of such a walk, this alone would not be enough for Thomas’s purposes. Surveyors and runners were hired, and it was determined that with a prepared path, as many as sixty miles could be covered by the right men; enough to include the Forks of the Delaware, a particularly valuable area of land for investors and settlers. With an altered, perhaps completely fake, copy of the 1686 document in tow, James Logan claimed at the next set of negotiations that it was proof of a walking purchase that had been “signed, sealed, and paid for.” Logan brought a minister and justice of the peace well known to the Lenape to swear the veracity of the document, and reminded the natives of the fair dealings William Penn had always had with them.

Nutimus was not swayed, pointing out that it was logically impossible that such a deal was made; the natives said to have made the deal had no claim upon the land in question. Not all of the Lenape chiefs were as adamant, but ultimately Logan failed to make the deal. It was not until the final, fateful 1737 negotiations in James Logan’s own estate that an agreement was reached. The Lenape chiefs claimed that the 1686 document was valid, but that they had not been paid for it, essentially making a compromise proposal: they would give up some of the land Thomas and Logan seemed to so desperately desire, so long as they were paid fairly. Logan, sensing victory near, pressed the claim that they had already received compensation. The Lenape responded with an explanation for their reluctance to acknowledge the treaty, claiming that they were unsure of the Walk’s route. Considering that abuse of this detail, likely one removed from the original document, was exactly what Thomas Penn and James Logan had planned, the Lenape concern was more than justified.

To counter the perceptive Lenapes’ suspicions, Logan called forth what was arguably the Europeans’ most powerful weapon: a cartographer. The map produced for the Lenape was not the survey showing just how far the runners were intended to go, but instead a distorted one, misrepresenting the far away Lehigh river as the relatively close Tohickon Creek, and including a dotted line showing a seemingly reasonable path that the “walkers” would take. Satisfied that the land in question was not so terrible a price to honor the old deed, the Lenape finally signed. The actual “walk” revealed that they had vastly underestimated the whites’ willingness to betray their guarded trust. Not only did the walk cover many times the distance they had expected, but the northern bound was not drawn due East in a direct path to the Delaware River like expected, but at a right angle of the Walk that resulted in nearly double the already considerable area being enclosed. Harper writes of the entire affair, “the Pennsylvania proprietors and their agents employed the European weapons of deeds, surveys, and maps to defraud and then dispossess Delawares [Lenape].” Never had the potency of such nonviolent armaments been as clear as when used in the removal of the Lenape claim to land. James Logan and Thomas Penn got what they wanted, but the Lenape could never forgive such a deep betrayal.

The late William Penn had earned a great deal of trust from the Lenape, working hard to make his idealistic dreams a reality. James Logan had cited this trust throughout negotiations with the Lenape; part of the reason the suspicious treaty had been honored at all was because of the respect the Lenape held for the man they believed wrote it. In some ways Thomas Penn paid quite dearly for the land, it had come at the price of the kingdom his father dreamed of. There had certainly been moments of unrest before, but always the problem was settled and a relative peace remained. After the Purchase things steadily grew worse; the Lenape forever held deep resentment towards the men who had tricked them.

There is evidence that the Lenape did formally complain of the inherent unfairness in the Walking Purchase for quite some time, but the general policy of Pennsylvania was not only to ignore it, but to silence it where possible. When the complaints persisted an Iroquois chief, Conassatego, was pressured into giving a scathing speech to the Lenape claiming they were a conquered nation, had no right to the land, and should leave it immediately. The speech chastised the Lenape greatly, emasculating them in the eyes of other natives, and made it clear they would find neither sympathy nor justice from anyone.

The suppression of Lenape complaints and the Iroquois speech probably served to exacerbate Lenape dissatisfaction, as well as the greater than ever influx of settlers slowly forcing them off their lands. It is not surprising then, that many of the Lenape sided with the French during the French and Indian War in order to strike back at the nation that had so betrayed them, as well as to regain their masculinity through warfare. William Pencak cites a Lenape message to Jeremiah Langhorne, a chief justice, that warns, “If this practice must hold why then we are No more Brothers and Friends but much more like Open Enemies.” This sums up neatly the ultimate result of the treatment the Lenape received at the hands of their “brothers.” Not all of the now dispersed Lenape fought against the English, but many found it their only option.

The bloodshed did not end with the French and Indian War, and when the charismatic Ottawa chief Pontiac, along with the Delaware prophet Neolin, called for war upon the British even after the French surrender, many Lenape joined their cause. It was perhaps due to their growing anger towards the settlers who had swindled and displaced them that so many brutal raids upon barely defended homesteads occurred, inflaming racial hatreds between the whites and natives further. By 1755, over 50 settlers had been killed in Indian attacks within the bounds of the original Walking Purchase, including Edward Marshall’s wife, eldest daughter, and son. Relations between the Pennsylvanians and the nearby natives deteriorated further and further, until finally a mob of angry settlers called the Paxton Boys descended upon a defenseless and friendly enclave of Conestoga natives. This slaughter revealed that the settlers’ view of the natives grew dimmer and dimmer every time they heard of an Indian raid. Pennsylvania’s relationship with the natives had gone from peace to war, and neither side was likely to ever reconcile.

The legacy of the Walking Purchase is as evident in what is not present in Pennsylvania today as what is. Even before the purchase, Lenape had been trickling out of their ancestral land to the west in response to the white settlements shrinking their own world more and more. With the completion of the Walking Purchase nearly all were forced to leave; Nutimus and most of the Lenape moved to the Susquehanna, but many others dispersed throughout lands that were yet unclaimed by the whites. The Lenape have no appreciable presence in modern Pennsylvania, and like many Native Americans, their culture is slowly disappearing. If there ever really was a Peaceable Kingdom, William Penn’s sons and James Logan had sold it, and if it was nothing more than a myth then they certainly dispelled its illusion.

What does remain of the Walking Purchase are the monuments that commemorate it, though as Dr. B. F. Fackenthal said at the unveiling of a monument erected in Springfield Township, Bucks County, at the site of the three walkers’ lunch, “This monument is not erected to glorify the Indian Walk, as all true Americans should blush with shame for the injustice done…” Another marker exists at the start of the walk in Wrightstown, PA. Other markers exist at Northampton, Edelman Mill, and Gallows Hill, all located along the route taken during the infamous walk.

Before the Walking Purchase, relations between the Lenape and European settlers were influenced deeply by William Penn’s vision of a Peaceable Kingdom. For some time it seemed as if his vision could be a reality; the Lenape became accustomed enough to the ways of the settlers that they could bargain wisely, baffling some of Pennsylvania’s toughest negotiators. Even after William Penn’s death, his legacy continued to influence relations, inspiring compromise and peace where otherwise might have been great bloodshed. With the Walking Purchase everything William Penn had worked and hoped for regarding the Native Americans was lost. Pennsylvania would not be some special place where natives forever lived in harmony with settlers. The actions of Penn’s children and James Logan ensured that the Peaceable Kingdom would end in blood and tears.

Sources:

- “Becoming American: The British Atlantic Colonies, 1690-1763.” nationalhumanitiescenter.org.National Humanities Center, n. d. 11 Nov. 2009 <http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/becomingamer/growth/text7/indian...

- Bierhorst, John. Mythology of the Lenape. Tucson: U of Arizona P, 1995.

- Fackenthal, B. F., Jr. “The Indian Walking Purchase of September 19 and 20, 1737.” Pennnsylvania Historical Commission. Springfield Township, Bucks County, PA. 25 October, 1925. Address.

- Geiter, Mary K. William Penn. Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited, 2000.

- Grumet, Robert S. The Lenapes. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 1989.

- Harper, Steven Craig. Promised Land. Bethlehem: Lehigh UP, 2006.

- Kenny, Kevin. Peaceable Kingdom Lost. New York: Oxford UP, 2009.

- Pencak, William and Daniel K. Richter, eds. Friends and Enemies in Penn’s Woods. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 2004.

- Schutt, Amy C. Peoples of the River Valleys. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 2007.

- Davis, W. W. H. “The Walking Purchase, 1737.” The History of Bucks County, Pennsylvania. n.p., 1905.

- Richter, Daniel K. Wars for Independence: Pennsylvanians and Native Americans 1750-1800. Institute for the Arts and Humanities at the Pennsylvania State University. 110 Business Building, University Park, PA. 8 Oct. 2009. Lecture.

- Weslager, C.A. The Delaware Indians. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 1972.

- William Penn his own Account of the Lenni Lenape or Delaware Indians 1683. Moylan, Pennsylvania, 1937.