Pete Seeger must have asked himself at a very early age, “What is folk music?” Son of a respected ethnomusicologist and folk singer by profession, Seeger, now 91 years old, has spent his life amplifying and exposing the value of folk music. Seeger embraces folk music as a living process, a music that changes with the people. For this reason, Seeger, as well as other “folkies” such as Alan Lomax, Woody Guthrie, Paul Robeson, Lee Hays and Irwin Silber, banded together to create a publication that would grow alongside folk music tradition and assist in the growth and preservation of folk music. Sing Out! Magazine is the culmination of this effort.

Yet, Seeger and the “folkies” conceived Sing Out! Magazine to be more than a digest of folk tunes. The publication took root in a time of civil unrest. World War II remained fresh in the minds of all people, it was the start of the “red decade” where conformity was demanded, the Old Left was making way for the New Left and people were fighting for their civil rights, equality and justice. Because Sing Out! was a publication of people’s music, there was no way it could ignore the people’s struggles.

Sing Out! first appeared under a different name, the more politically charged People’s Songs. It published civil rights songs, songs of peace and traditional ballads. It favored equality and served as a prototype for the New Left, a group that disregarded the Stalinist focus on organization held by the Old Left. People’s Songs focused on being a non-commercial magazine that could not be found in common music outlets. Music and political activism meshed within its pages and the publication reached approximately 3,000 subscribers. However, after financial difficulty – a problem that would plague the anti-commercial publication – People’s Songs was forced to shut down in 1948.

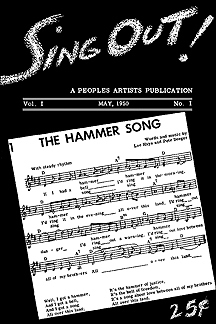

Two years later, in May 1950, the first issue of Sing Out! was published after some restructuring. Located on East 14th Street in New York City, the magazine set off with Editor Irwin Silber and staff, including Paul Robeson, Earl Robinson, Waldemar Hille, Howard Fast and Sidney Finkelstein. Pete Seeger and Lee Hays’ song, “The Hammer Song,” adorned the cover. This song proclaims:

Well, I got a hammer

It’s the hammer of justice,

And I got a bell.

It’s the bell of freedom,

And I got a song

It’s a song about love between all of my brothers

All over this land;

All over this land.

Sing Out! saw commercial music as becoming detached from the people; too commercialized and lacking human soul. By placing the peoples’ music front and center, the new magazine proposed to join the true emotions of man – fear, harmony, excitement, anger and love – with music once again. There was humanity in folk music and the songs were Sing Out!’s tool for connecting the people and revitalizing folk tradition. Each issue contained instructional material on how to play traditional folk music. Robert Cantwell states in his book When We Were Good, “Between 1950 and 1952 Sing Out! urged its readers to carry [these folk songs] to schools, summer camps, and other small venues.”

The magazine was lauded by individuals like Margot Mayo, a writer and teacher of music. She reports that folk songs have been some of the most popular amongst her young students. Songs that could only be found in the pages of publications like Sing Out! Songs like “We Will Overcome,” “This Land Is Your Land,” “The Hammer Song,” and “The Midnight Special” enamored her students and she praises the magazine for providing material for her to teach these songs in the classroom. Pete Seeger recalls in an interview with Will Schmid, “Incidentally, for [many] years this little magazine has made it possible to get songs that you couldn’t find anywhere else.”

Pete Seeger continued his contribution to Sing Out! by writing “Johnny Appleseed, Jr.,” a column which included his personal thoughts of the state of folk music and theories that asked readers to denounce the commercialism of popular music and focus on the people. He would recount his every day musings and often discussed music he discovered while travelling.

In 1962, the magazine contained an article introducing Bob Dylan, whom they praised as having truthful lyrics and a simplistic yet traditional method of playing music. Dylan was influenced by one of the magazine’s founders, Woody Guthrie– folk singer and political activist. Dylan would be the forerunner to the booming popularity of folk tunes in the coming years.

Folk music’s popularity began to take rise. College-aged students drew from the music’s politics and non-conformity to create their own counterculture. This boom in folk music greatly assisted Sing Out!. Cantwell, in When We Were Good, describes, “by 1962 [Sing Out!’s] circulation more than doubled — a subscription list of 500 in 1951 grew to 25,000 in 1965.” Groups like The Kingston Trio became popular due to the counterculture’s boost, but with popularity also came the recurrence of commercialism and conformity. Purists argued that the new wave of folk was not genuine folk music because did not fit the oral traditions of the music. Others chastised the music for lacking political content. Yet, many embraced the new styles erupting from the folk music boom.

Sing Out! was divided over the new popularity of folk music. Should it be embraced or reprimanded for now being so commercialized? Advertisers swamped the magazine. Moses Asch, in his article “To My Fellow Advertisers,” insisted that Sing Out! advertisers only submit truthful ads, as the magazine would not accept commercialized gimmicks. Although Sing Out! was greatly assisted by the money put forth by advertisers, it refused the hypocrisy of allowing commercialism to take hold in the publication.

The magazine had its share of problems. Irwin Silber states that Sing Out! essentially worked “hand-to-mouth” and frequently met with threats of extinction due to financial meltdown. Rampant McCarthyism blacklisted several individuals tied to the magazine; one of these individuals being Pete Seeger. He recalls the blacklisting with little animosity though, as it gave him the opportunity to interact with new crowds and people. Yet, the blacklisting did cause a drop in readership. The magazine had some controversy over the blacklistings. After a reader had called for the jailing of Pete Seeger, Irwin Silber responded, “It is a sad day in the life of any nation when its artists must face the possibility of jail for artistic non-conformity.”

The review of Bob Dylan’s performance at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 created, perhaps, the greatest controversy for Sing Out!. Bob Dylan debuted his “electric” style (using an electric guitar instead of acoustic) upsetting many folk purists. Irwin Silber portrayed the situation as disingenuous. Sing Out! compiled several accounts of the Dylan incident. Some praised the new style; others condemned Dylan as “no longer a neo-Woody Guthrie, with whom they could identify.” From this event, the magazine garnered somewhat of a folk-purist image. Irwin Silber contends in his interview with Richie Unterburger that Dylan’s switch to electric was not the defining point of his criticism. Instead, Dylan’s “moving away from his political songs” is what upset most “folkies”. “Folk-rock” the culmination of the merge in electricity and folk music, was widely unmentioned by the magazine at this time, preferring to vitalize traditional songs rather than aggrandize commercial tunes.

In 1968 Irwin Silber left the editors seat and made way for Happy Traum, who saw great opportunity in the magazine. Rather than shunning new folk artists like Dylan and Phil Ochs, he allowed the magazine to embrace new traditions. This effectively fought Sing Out!’s purist stigma.

Sing Out! initially took an anti-war stance as the Vietnam War occurred. However, the publication’s readership was not unified behind this viewpoint. The readership was torn; therefore the editorial staff had to make adjustments. Sing Out! devised a compromise by henceforth lessening the political content in the magazine and focusing on music. Cantwell, in When We Were Good, states, “[Sing Out!’s] credo was that of a global youth movement without an articulated politics.”

Traum soon turned over the editor’s chair to Bob Norman. Norman focused on making an impact on the massive debt that had piled up on the magazine since its inception. The magazine’s financial difficulty had forced strict budgeting. Irwin Silber commented that the magazine was “teetering” after his departure, and it took a long time for Sing Out! to regain normalcy after the financial crisis.

In the 1970’s, readership declined as folk music had lost a great deal of mainstream popularity. Editors came and went. However, all was not lost. Most contemporary folk magazines had disappeared by the late seventies. Sing Out! survived. As rent prices increased in New York City, the magazine relocated to its current location in Bethlehem, PA. Thanks to the efforts of current editor Mark Moss and the contributions from readers and dedicated folk artists alike, Sing Out! magazine was reborn, and in 2000, Sing Out! celebrated its 50 year anniversary.

The magazine, now with a smaller, though heavily devoted, readership, has reached its niche. The magazine continues to provide readers with traditional folk songs and interviews of artists that are currently impacting folk music. Today it plays a significant role in the preservation of traditional folk music while also displaying contemporary artists with folk roots.

Over the years, Sing Out! has grown to be much more than a magazine. Sing Out! currently publishes a widely used folk tradition song book Rise Up Singing. Sing Out! recently acquired Legacy Books, which offers some of the most informative folklore literature available. The Sing Out! Radio Magazine is a widely aired radio show containing folk music and interviews. The magazine also partakes in various music festivals such as the Philadelphia Folk Festival, the Old Songs Festival, the Clearwater Festival, Merlefest, the Falcon Ridge Folk Festival, the Walnut Valley Festival, and Bethlehem’s own Musikfest, among others.

Sing Out! magazine’s large collection of music, documents, photographs, film, newsletters, periodicals, back issues, literature and song books, known as the Sing Out! Resource Center (SORCe), is one of the largest collections of its kind. It contains hundreds of thousands of items that have been either donated or collected over the magazine’s fifty-plus year publishing existence. Currently the Sing Out! staff is available to assist with any queries about the collection, also visitors are welcome to peruse the resource center. The Sing Out! Resource Center recently collaborated with the Oberlin College to create The Folk Song Index, a database of traditional folk songs.

A contributor to The Mudcat Café, a folk music discussion website, has the following to say about Sing Out! Magazine:

This magazine is where I first heard about Victor Jara and his music and life. Back then I wanted to know who were Don and Connie West and their daughter, Hedy and many others. Years ago I [hitchhiked] there just to see the place. In a way this magazine plants the seed and it goes from there. I think in the long run this magazine should be around for some very young kid to read and wonder who are these folks and their music.

Currently thriving in Southside Bethlehem, PA, Sing Out! has a bright future paved out for itself.

Sources:

- Asch, Moses. “To My Fellow Advertisers.” Sing Out! 14:6 (1964). 1.

- Cantwell, Robert. When We Were Good: The Folk Revival. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996. 269; 272; 280.

- Deitz, Roger. “’If I Had a Song…’ A Thumbnail History of Sing Out! 1950-2000 … Sharing Songs for 50 Years!” Sing Out! History. 1995; 2000. 22 Jan. 2010. <http://www.singout.org/sohistry.html>

- Denisoff, R. Serge. “The Proletarian Renascence and Urban Folksinging.” The Journal of American Folklore 82:323 (1969). 61-62.

- Lomax Hawes, Bess. “Reminiscences and Exhortations: Growing Up in American Folk Music.” Ethnomusicology 39:2 (1995). 179-181.

- Lund, Jens and Serge Denisoff. “The Folk Music Revival and the Counter Culture: Contributions and Contradictions.” The Journal of American Folklore 84:334 (1971). 394-405.

- Mayo, Margot. “Five Years of Folk Song Favorites.” Sing Out! 12:1 (1962). 37-39.

- Nelson, Paul. “Another Review.” Sing Out! 15:5 (Nov. 1965). 6-8.

- “Pete Seeger wants you to save SingOut.” The Mudcat Café. 17 February 2010. <http://www.mudcat.org/thread_pf.cfm?threadid=125136>

- Rich, Arthur L. “American Folk Music.” Music and Letters 19:4 (1938). 450-452.

- Schmid, Will. “Reflections on the Folk Movement: An Interview with Pete Seeger.” Music Educators Journal 66:6 (1980). 42-46; 78-79; 81.

- Silber, Irwin. Sing Out! 12:4 (1962). 67.

- Silber, Irwin. “Review of Newport 65.” Sing Out! 15:5 (Nov. 1965). 4-6.

- Sing Out! 1:1 (1950). Cover; 1.

- Sing Out! 12:4 (Oct.-Nov. 1962). 2-8.

- Tachi, Mikiko. “Commercialism, Counterculture, and the Folk Music Revival: A Study of Sing Out! Magazine, 1950-1967.” The Japanese Journal of American Studies 15 (2004). 187-211.

- “The Sing Out! Resource Center.” Sing Out! 24 February 2010. <http://www.singout.org/sorce.html>

- Unterberger, Richie. “Irwin Silber Interview.” Perfect Sound Forever. 25 January 2010. <http://www.furious.com/Perfect/irwinsilber.html>

For More Information:

- “If I Had A Song...” Sing Out! Official Website. 24 Oct. 2011. <http://www.singout.org/sohistry.html>.

- “A History of Sing Out! Magazine.” YouTube. 13 Nov. 2011. 24 Oct. 2011. <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9w8stlIMhII>.