If an episode of the game “who am I?” went as follows, many Americans would surely get it right. “After spending time working my way up through the minor league systems, I broke the race barrier in Major League Baseball on April 15, 1947. Who am I?” Jackie Robinson. Now if a shorter, and slightly altered version were played with the clue, “I’m the first African American man to ever play professional baseball,” you would be hard pressed to find someone that could respond with the correct answer. The major contributing factor for the mistake is the incorrect assumption that Major League Baseball and professional baseball are one and the same. Long before the Major Leagues were an organization, other professional leagues existed throughout America. The first true integrator of professional baseball in these leagues is John W. ‘Bud’ Fowler.

Bud, as he came to be known from the way he would greet others, made this historic first in 1878. Pennsylvania gets to share in this claim to fame as Bud Fowler first played for a team located in New Castle, Lawrence County. Born on March 16, 1858 to parents John W. Jackson and Mary Lansing Jackson, John W. Jackson Jr., ‘Bud’ changed his name when he started his quest to make it in professional baseball. It has been speculated that this name change was done by Fowler in order to avoid trouble with his previous name relating back to his parents, and the possible conflicts it could create for them.

Athletically speaking, Bud Fowler was not someone who immediately stood out or was intimidating; standing 5 foot 7 inches and weighing 155 pounds, he was clearly no giant. Fowler instead made up for his average size with amazing natural ability. With an uncanny ability as both a pitcher and catcher, Fowler’s competitive drive helped him in his constant battle with racism and segregation.

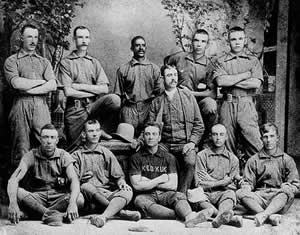

The Baseball Biography Project illustrates how Fowler’s competitive edge outweighed the negative pressures of crossing racial barriers, writing: “He was the first to play on integrated teams, typically the only dark face on the roster; in fact, he preferred white clubs because they fielded the best nines and offered the stiffest competition through much of his career. As such, he was the first significant black player in the United States.” There was no doubt that the journey Fowler was embarking on would bring him face-to-face with hatred, racism, and likely forms of violence, but he was determined to rise above these obstacles in order to play the game he loved with and against the best players of the game. He stood up for the rights he felt were divinely-given to him and all colored people, as it was phrased at the time.

The Negro League Baseball Player Association credits Fowler with the creation of shin guards, which came as a direct response to the adversity Fowler placed on the field. As the story goes, Bud created the shin guards in response to dirty play by his white opponents. Fowler got spiked very frequently by white players who were coming home when he was catching. Spiking refers to a player sliding home and purposely attacking the defensive player with the spikes on the bottom of their cleats.

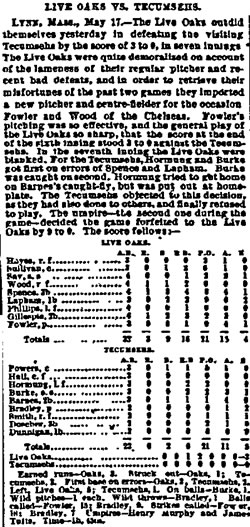

The abuse and hostility Fowler was subjected to was not limited to physical abuse. The media played a large part in attempting to hurt and dishearten him. In 1884, when Fowler was playing for Stillwater in Minnesota, “an opposing white player welcomed him to the league. As the St. Paul Daily Globe noted, ‘Fowler, the lightning colored catcher for the Stillwaters, had his foot spiked by a base runner at home plate breaking the bone of his big toe.’” After being told by the surgeon that “It will be several days before he [Fowler] can play again,” Fowler responded that he would be up to bat again on Saturday. On his return, Fowler hit a double and stole two bases, further exemplifying his strength, courage, and determination.

Later in his career while playing in Binghamton in 1887, a quote appeared in Sporting Life, “Joe Ardner, in one game he played, shows himself to be… far superior to the ‘coon’ Fowler on second base.” The racism towards African American players seemed as if it would never go away. An anonymous player from Fowler’s time gave an interview in The Sporting News that revealed the validity of the claims that players and the media and even umpires were out to get Fowler and the other African American players that followed in his footsteps.

Essayist Brian McKenna reports that “‘Fowler used to play second base with the lower part of his legs encased in wooden guards. He knew that about every player that came down to second base on a steal had it in for him and would, if possible, throw the spikes into him…[Also] about half the pitchers try their best to hit these colored players when [they’re] at the bat.’ Furthermore, league umpire Billy Hoover admitted to calling close plays against clubs that fielded black players.” Fowler’s experiences throughout his career created an environment that many people today would likely not have been able to work through. Bud Fowler’s ability to rise above the racism which reared its ugly head at him on a daily basis is truly inspiring.

The problems Bud Fowler faced in breaking into professional baseball with the Newcastle team were the same problems Jackie Robinson would face 70 years later. Bud Fowler deserves to be recognized in the history of baseball for the fight he put up against the racist attitudes that once dominated our country. After all as McKenna states, “John Fowler was one of the true pioneers of American baseball, one so far overlooked by the National Baseball Hall of Fame. In black baseball history, he is the pioneer.”

Sources:

- McKenna, Brian. “Bud Fowler.” The Baseball Biography Project. Society for American Baseball Research. 10 Nov. 2010 <http://bioproj.sabr.org/bioproj.cfm?a=v&v=l&bid=3116&pid=19716>.

- “John W. ‘Bud’ Fowler.” Negro League Baseball Players Association. 2007. 10 Nov. 2010 <http://www.nlbpa.com/fowler__john_w__-_bud.html>.