Jeans have them. Purses do, too. They can be found on backpacks, boots and bags, sleeping bags, sweaters, and suitcases. From coats to coolers, zippers are everywhere. It is difficult to believe that this now ubiquitous invention struggled to make it to shelves, but thanks to a few dedicated inventors, managers, and salesmen in Meadville, Pennsylvania, people everywhere can avoid the hassles of buttoning their pants and parkas, opting instead for the zipper's irresistible combination of "simplicity and complexity."

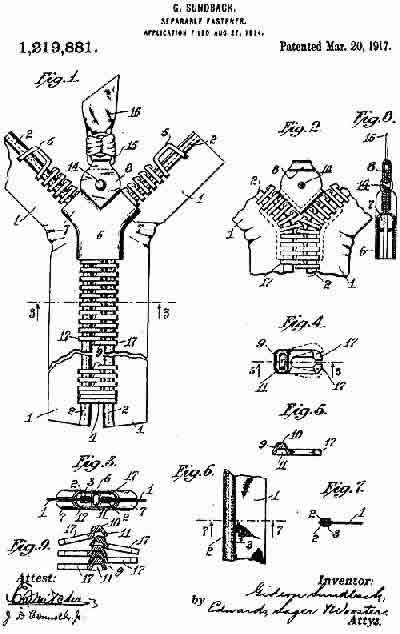

The issue of where, how, and when the zipper was first invented has been steeped in controversy. Whitcomb Judson was the first to come up with the idea of a metal zipper in 1893, which he referred to as a "clasp locker." Judson's clasp locker consisted of a complicated hook-and-eye fastener that was used to open shoes. Judson designed this device for the Automatic Hook and Eye Company, but his design could not be mass produced easily and had the unfortunate habit of popping open unexpectedly. Luckily, Swedish inventor Gideon Sundback created a design that used a slider and two rows of metal teeth. Sundback's creation was more durable than Judson's and was much cheaper to produce. Because of these improvements, Gideon Sundback holds the patent for the "zip fastener." As the patent holder, Sundback is commonly acknowledged as the inventor of the zipper. In 1906, Lewis Walker, who was excited about Sundback's new design, took over control of the Automatic Hook and Eye Company, renaming it the Hookless Fastener Company.

Walker made the crucial decision to move manufacturing operations to Meadville, citing a "wish to locate in a community where there is a minimum of labor troubles, where there are ample express facilities... and where the members of the concern and its employees may enjoy the comforts and advantages of pure air and water, good schools and wholesome influences," a city that was, according to Robert Friedel in Zipper: An Exploration of Novelty, "in spirit, as well as in time and place... very close to the Zenith of Sinclair Lewis's Babbit." By November 1913, the newly named company was producing a thousand zip fasteners a day.

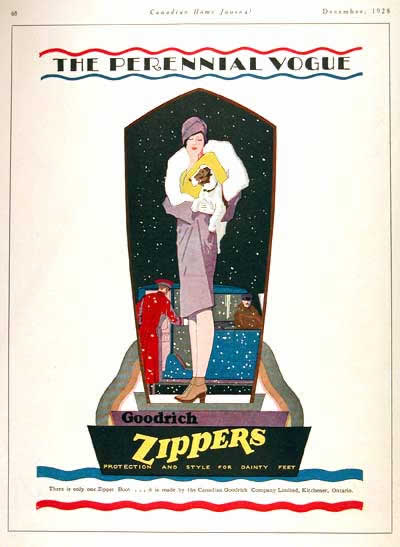

Although Hookless was capable of producing mass quantities of the fasteners, they initially lacked the outlets to sell their product. In 1921, B.F. Goodrich Rubber designed galoshes that would use Sundback's fasteners. The boots, which were originally going to be named the Mystik Boot, were renamed the Zipper when Goodrich employees reported that the company's president showed "boundless enthusiasm" for the new design. The term "zipper," initially the name of just the boot, eventually came to signify Sundback's invention as well. Even though the boots were popular and helped Hookless turn a profit, they were the only major product affiliated with the fastener company. Friedel effectively summarizes the situation: "when Goodrich's Zipper Boots sold, the fastener sold; when they did not, the fastener didn't."

In 1937, some major changes took place. First, the Hookless Fastener Company changed its name again to Talon, Inc. The name change was advantageous because it could be printed on the zipper tab itself, and it was easier for potential buyers to remember. In the same year, the zipper began to gain notoriety for its use on clothing. The Prince of Wales notably wore a suit with a zipper and more clothing designers began to incorporate zippers into their fashions. With new colors available, zippers became a must-have item on clothing of all types.

Fortunately for the clothing industry, Talon was located in an ideal city to meet the demands of the newest fashion fad. According to Friedel, Meadville "had become a modest but important center of toolmaking... [it] was an environment in which the zipper makers could grow as fast as their capital and their markets allowed." In a decade when most other companies were firing workers and struggling to survive, Talon's Meadville factories had to go to twenty-four hour production to meet demand. At the height of the zipper's popularity, the Meadville zipper factories employed 5,000 workers—out of a town with fewer than 19,000 people. Zipper making became, in Friedel's words, the "economic heart and soul of Meadville."

Talon had its best year ever in 1941, when demand for the zipper earned the company thirty-one million dollars in sales. Months later, wartime shortages dried up the supplies of copper alloy that the Meadville factories needed for their machines. For Meadville, the boom was over. Talon's Meadville operations never recovered. Shortly after 1960, the struggling company was purchased by Textron, Inc. but then re-sold in 1968. The Meadville managers, who tried to turn the company around, eventually were forced to sell the zipper company to the British textile company Coats Viyella PLC in 1991.

While Talon fruitlessly attempted to revive its pre-war boom, Japanese manufacturer YKK capitalized on a worldwide demand for zippers. YKK opened a plant in New Zealand in 1959, followed in successive years by plants in the U.S., Malaysia, Thailand, Costa Rica and other textile-producing countries, taking full advantage of the cheaper labor offered by many of these nations. By constructing plants closer to areas of consumption, YKK provided itself with a more responsive distribution network, guaranteeing timelier product delivery. By 1991, YKK had an international presence in forty-two countries, with a mere thirty percent of its 1.25 million miles of zippers being produced for domestic consumers. YKK surpassed Talon for the American market sometime in the 1980s, forcing Talon to later forgo the zipper business.

Talon's rise and fall mirrored that of Meadville as well. The loss of manufacturing during the late 1970s and early 1980s created an unemployment rate just under twenty percent. The loss of Talon for good in 1993 left economic wounds that still have not fully healed. The expressways on the western side of Pennsylvania skirt Meadville by a few miles, giving the impression that the twenty-first century has left this town behind. The smokestacks that indicate Meadville's productive past now seem aimless. Although some things are still manufactured in Meadville, Friedel remarks that "zippers are not among them... only by straining a little bit can one make out a faded "Talon" on one or two of the outlying brick buildings." These days, the closest that Meadville comes to the zipper is in the name of its local radio station, WZPR, a reminder that this Pennsylvania town was responsible for one of the most useful inventions of the last century.

Sources:

- Crosbie, Betty Ann. "No need to shy away from installing zipper." The Toronto Star 20 Feb. 2003, Ontario ed., Fashion sec.: D04.

- Dulken, Stephen Van. Inventing the 20th Century: 100 Inventions That Shaped the World. Washington Square, NY: New York UP, 2000.

- Friedel, Robert. Zipper: An Exploration in Novelty. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1994.

- Fulford, Benjamin. "Zipping up the world." Forbes. 24 Nov. 2003. 25 Mar. 2009. <http://www.forbes.com/global/2003/1124/089.html>.