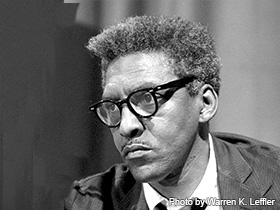

Born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, on March 17, 1912, Bayard Rustin was a political activist and essayist. He is most famous for planning the historic "March on Washington." Throughout his life, Rustin held important executive positions in politically active groups such as the Fellowship For Reconciliation (FOR), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and the A. Philip Randolph Institute. Rustin died of cardiac arrest in New York City, on August 27, 1987.

Born in March 17, 1912, in West Chester, Pennsylvania, Bayard Rustin was raised by his maternal grandparents. His grandmother, Julia Rustin, had a profound influence on him while he was growing up. In 1932, Rustin left West Chester to attend Wilberforce University in Ohio, an historically black college.

During the summer of 1941, Rustin helped A. Philip Randolph, founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the most influential African-American labor union, organize a protest march intended to coerce President Roosevelt into desegregating the armed forces. In response, Roosevelt ended employment discrimination, but not military segregation. Randolph, like many in the African-American community, considered this a victory, but Rustin did not. Dissatisfied with Randolph's results, Rustin turned towards the pacifist movements, joining the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), headed by A.J. Muste. FOR's approach differed from other pacifist movements because it applied Mahatma Gandhi's nonviolent direct action, which involved actual confrontation. Nonviolent direct action required protesters to "seek out" violence against them, yet not fight back, making the oppressor's brutality and injustice all the more evident. Rustin helped FOR apply its strategy in Southern communities; FOR had previously only worked in Northern states.

In 1942, Rustin began to write essays on the politics of racism, such as "Nonviolence vs. Jim Crow" and "Letter to the Draft Board" in 1943. By the late 1940s, Bayard Rustin had become an internationally renowned political activist and pacifist.

In 1953, in Pasadena, California, Rustin engaged in consensual sexual activity with two men and was arrested on charges of lewd conduct. He was sentenced to serve 60 days in jail. When the story appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Muste accepted Rustin's resignation. Like most black leaders, Muste saw Rustin's homosexuality as a flaw that could be used to discredit the Civil Rights Movement.

In 1956, Rustin helped Martin Luther King, Jr. during a series of bus boycotts in Montgomery, Alabama, coordinated by the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA). Rustin was recommended to King by Randolph, who believed the protest needed Rustin's organizational skills and experience. NAACP leadership objected to Rustin's involvement, but King decided to use Rustin despite the risk he posed the cause. The boycotts inspired a whole series of essays that Rustin wrote during the mid 1950s: "Montgomery Diary", "Fear in the Delta", and "New South...Old Politics." Rustin also advised King on Gandhian principles and helped him understand the concept of Satyagraha: Nonviolence as a way of life and not merely a political tool. Much of King's later nonviolent resistance came directly from Rustin's teachings.

The Montgomery boycotts ultimately resulted in the creation of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957, an assembly of black southern ministers led by King. Rustin worked closely with the SCLC, helping to shape its themes and agenda.

In 1960, however, Rustin was coerced to resign from SCLC. Opponents threatened to release a fabricated story suggesting a homosexual relationship between Rustin and King, unless a planned march at the Democratic Convention was called off. King reluctantly accepted Rustin's resignation, but they continued to work together.

During the early 1960s, Rustin began to believe that economic, rather than political forces, were best suited to help the black cause. Thus he organized the March on Washington. In August of 1963, during which King delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech to a crowd of over 250,000 people and millions of TV viewers, Rustin made sure employment issues and civil rights legislation were at the heart of the march. Groups in attendance included the FOR, SCLC, NAACP, and many others. Though Rustin orchestrated the entire event, he was officially named only Deputy March Director in order to keep a low profile. The March on Washington proved to be an enormous success, becoming the largest public protest in American history. The influence of this event is evident in Rustin's writing at the time. Both "Preamble to the March on Washington" and "From Protest to Politics: The Future of the Civil Rights Movement," published in 1963 and 1964 respectively, made the case for moving from protests and boycotts to lobbying for civil rights legislation and job programs.

After the March on Washington, both the SCLC and the NAACP offered Rustin important executive positions. Rustin declined both offers, and instead joined the recently founded A. Philip Randolph Institute as executive director in 1965.

To Rustin, full employment for blacks was the most effective and practical way of winning equality in America. Because of his job-centered philosophy, he was widely criticized by many of his colleagues and labeled as a political conservative. Nonetheless, he continued to voice his opinions throughout the 1970s with a series of controversial essays: "The Blacks and the Unions" in 1971, and "Affirmative Action in an Economy of Scarcity" in 1974. He also published his seminal book on civil rights, Strategies for Freedom, during 1976.

By the late 1970s, he had begun heading many international humanitarian campaigns. He visited countries including Barbados, El Salvador, Grenada, and Zimbabwe, and became a powerful advocate for free elections. In 1979, he wrote an essay called "The War Against Zimbabwe," about the country's recent faux-election and the international community's response to it.

Rustin became outwardly vocal about his homosexuality during the late 1980s, with a series of essays on the subject. "The New 'Niggers' Are Gays," written in 1986, and "The Importance of Gay Rights Legislation," written in 1987 publicly announced Rustin's views on gay rights. Rustin himself declared that "remaining in the closet is the other side of prejudice against gays. Because until you challenge it, you are not playing an active role in fighting it." Rustin insisted that most of the necessary framework for the gay liberation movement had already been set in place by his own contributions to the Civil Rights Movement.

Rustin spent his final years involved in AIDS activism, the Randolph Institute, and international humanitarian causes. Shortly after returning from a visit to Haiti, Rustin died from cardiac arrest on August 27, 1987. He was 75-years-old.

Throughout his life, Bayard Rustin was responsible for many black civil rights breakthroughs. His ideas on nonviolent direct action, which influenced King, helped pave the way for a new form of social protest that changed America. But in spite of his contribution to social equality, his sexual orientation continues to prove troublesome even today. Recently, a West Chester public district underwent several debates over whether to name a high school after Bayard Rustin. Critics argued that Rustin's overt homosexuality invalidated him morally, but the school board stood firm and voted to approve the measure. This small victory, though insignificant against the civil rights battles that Rustin pioneered, is still symbolic in terms of a nation starting to fully recognize one of its most important humanitarian leaders.

Books

- Strategies For Freedom. New York: Columbia UP, 1976.

- Down The Line. Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1971.

Essays

- "Nonviolence vs. Jim Crow." Fellowship: The Journal of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, July 1942.

- "Guns, Bread, and Butter." War/Peace Report, March 1967.

- "From Protest to Politics: The Future of the Civil Rights." Commentary, 1964 issue.

- "Reflections on the Death of Martin Luther King, Jr." AFL-CIO American Federationist, May 1968.

- "The Total Vision of A. Philip Randolph." New Leader, 1969.

- "The Blacks and the Unions." Harper's Magazine, 1971.

- Anderson, Jervis. Bayard Rustin: Troubles I've Seen. New York: HarperCollins, 1997.

- Carbado, Devon and Weise, Donald. Time on Two Crosses: The Collected Writings of Bayard Rustin. San Francisco: Cleis Press Inc., 2003.

- D'Emilio, John. Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin. New York: Free Press, 2003.

- Levine, Daniel. Bayard Rustin and the Civil Rights Movement. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2000.

- Rustin, Bayard. Strategies for Freedom. New York: Columbia University Press, 1976.

- Woodward, C. Vann. Down the Line: The Collected Writings of Bayard Rustin. Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1971.

Ruskin, a key player in the civil rights movement, was the author of Strategies for Freedom: The Changing Patterns of Black Protest.